We talk to Jonas Kluger, the developer who, after studying design with a focus on film and animation at the Technical University in Nuremberg, first completed an internship at Trixter. His career then began as a VFX editor at Mackevision in Stuttgart. Over the years, his career has taken him to various VFX studios, including Marvel’s “The Avengers”, “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story”, “Transformers: The Last Knight” and several seasons of “Game of Thrones”. His team even won an Emmy for the latter! He is also a board member of the Visual Effects Society (VES) of the German Section.

DP: Let’s start from the beginning: As a compositor and VFXer, what happened when you developed software just like that?

Jonas Kluger: I discovered the need for VFX asset library software early on. It was often one of my tasks to tag new elements and sort them in a meaningful way. With a focus on the technical side and a passion for the creative, I have always been a fan of smart and simple workflows supported by useful tools.

It took 3 years, a short career change into software development and countless hours of perfecting the software with many beta testers around the world to finally present my own VFX asset library software: Das Element.

DP: What is Das Element anyway?

Jonas Kluger: In a nutshell, Das Element is an asset management software. It allows you to organize and sort videos, images and image sequences based on a VFX pipeline. Organize all your assets in a logical order and quickly find what you are looking for.

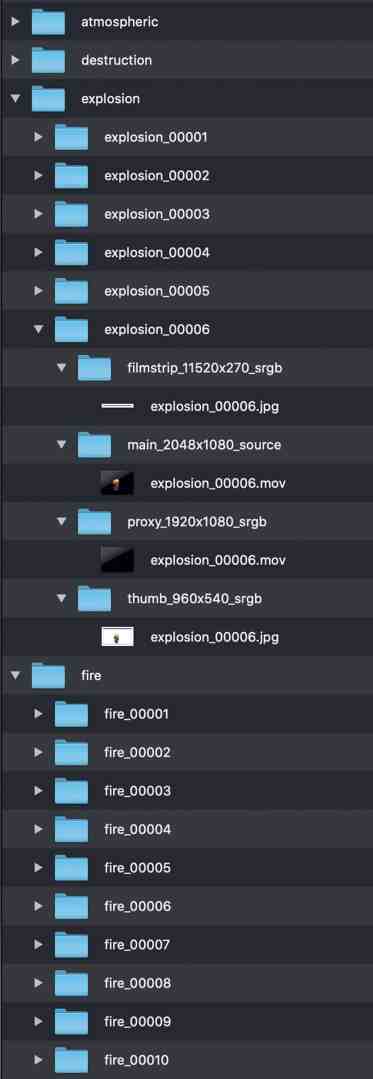

You can imagine it like this: You have a lot of images, video clips or other media files. You want to organize them all in a folder structure and then be able to find them easily and clearly using keywords and categories. Proxy formats are created for this purpose for a quick preview.

Related elements are collected in so-called libraries. You can create as many of these as you like. This allows you to create a global library for the entire studio or manage elements within specific projects. Many different types of VFX elements can be sorted. These can be Practical Elements, textures, reference images, PDFs, clips from the Internet or images from the Matte Painting Department. Whatever the user wants.

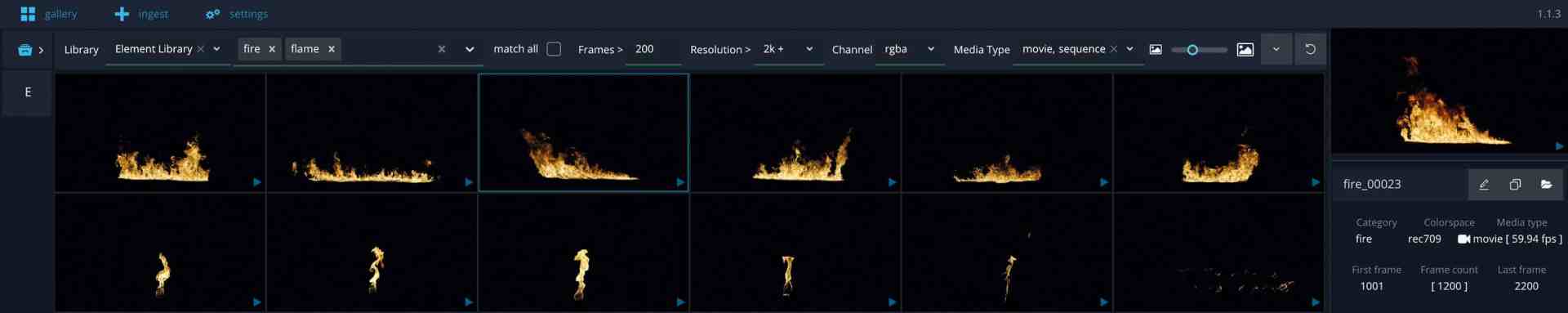

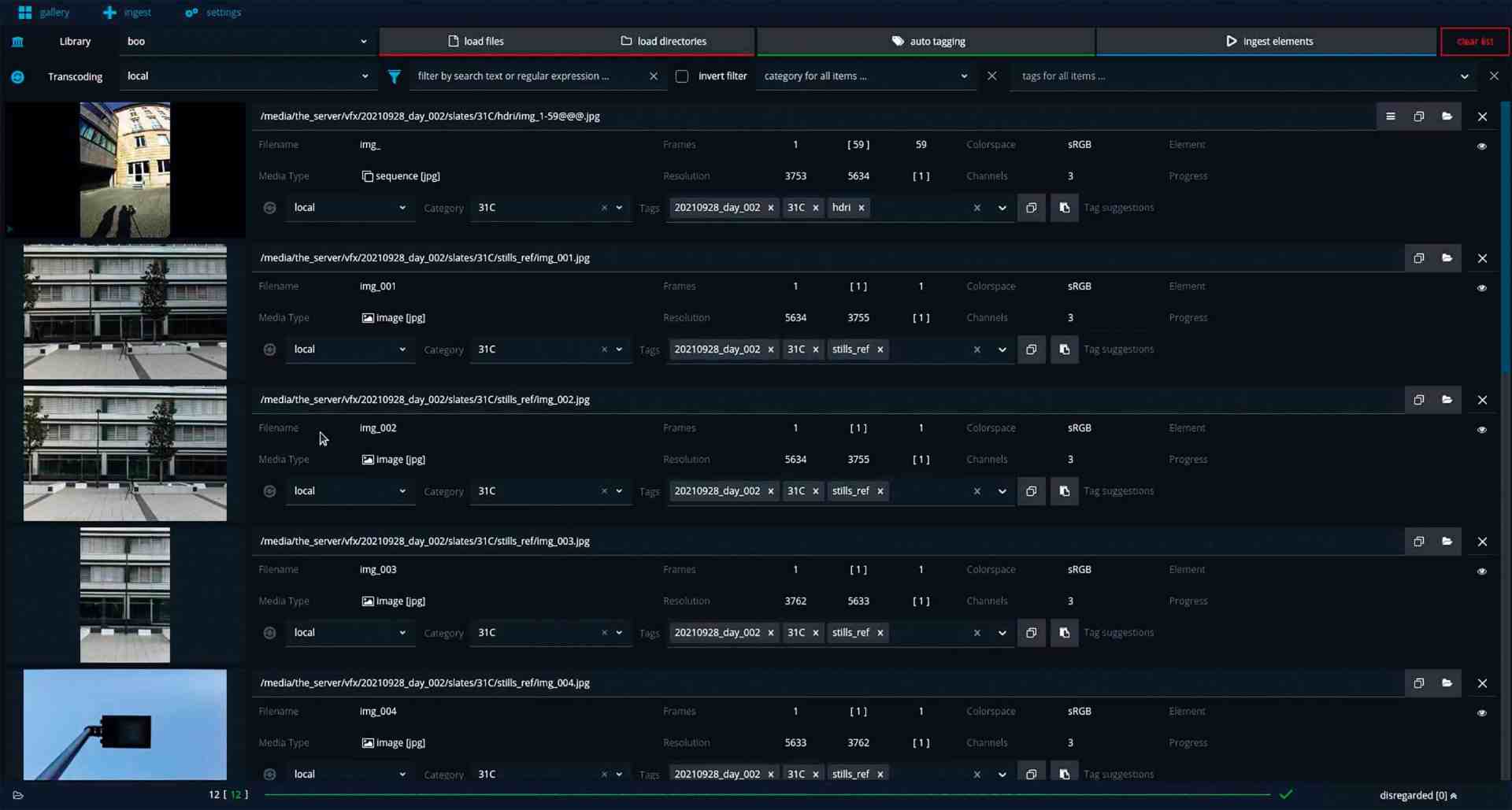

The software consists of three parts: the Gallery View, the Ingest View and the Configuration. The Gallery View allows you to search for and find assets. This is where artists will spend most of their time.

The Ingest View is used to select new elements to be added to the library. The software supports the user enormously in tagging the elements quickly and easily and adding categories. The better the elements are tagged, the faster you can find what you are looking for.

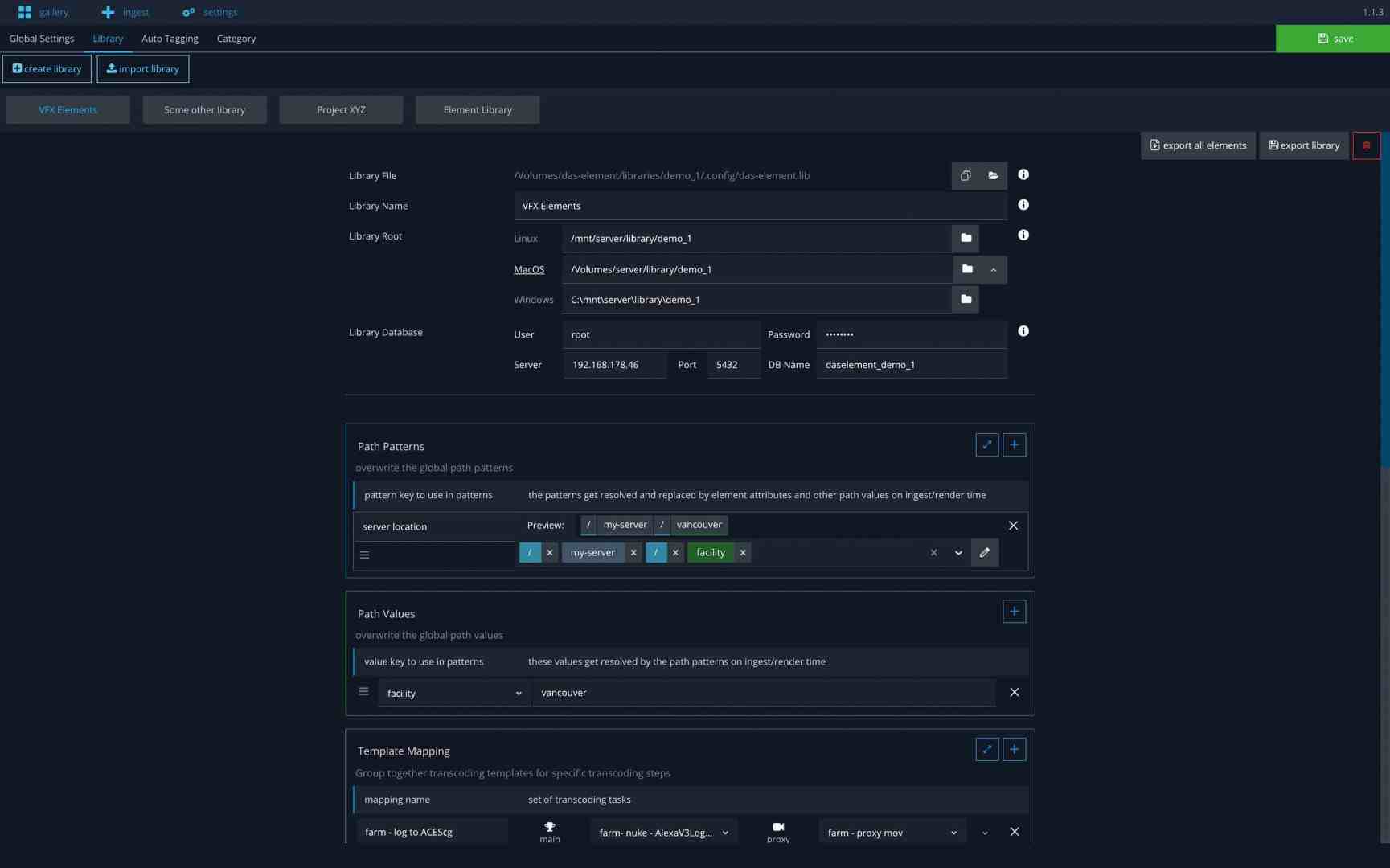

The third part consists of the configuration. With the default setting, you get a great structured folder structure, naming convention and the appropriate transcoding processes. You don’t have to worry about this, it happens automatically. However, if you have special requirements and want more freedom in this process, you can make your own settings. You don’t have to use the default. The software is cross-platform compatible and therefore runs on Windows, Linux and Mac OS operating systems. For example, it is no problem if you use Linux for compositing, while the matte painting department prefers Windows and Production Mac OS.

An important feature of the software is that it works completely offline, bucking the trend towards cloud solutions. A security feature of many studios is that only selected computers are allowed to use internet access. Artists rarely have the opportunity to upload or download data to servers. Das Element therefore operates offline, which has a very positive effect on performance. Another argument in favour of this is the reduced Internet traffic. This saves a lot of CO2 emissions and is good for the environment. Many people do not realize how much energy is consumed every time a website is accessed.

DP: So it manages assets – but in theory I can also do that with folders and a file manager, can’t I?

Jonas Kluger: The big advantage that is immediately apparent when using the software is that the user immediately gets a visual overview of all available elements without having to click through folder structures on the file system. Preview formats (proxies) are generated for each element entered, allowing the content to be analysed much more quickly without having to open individual files, which are often several gigabytes in size.

As a collection of many media files can quickly reach several bytes in size, you should think about storage space on the server. Depending on the length of the element, the file size of the proxies ranges

Element between a few Kbytes and a few Mbytes. The additional storage space can therefore be disregarded. As an artist, you don’t have to worry about folder structures or knowing where each file is located. File paths should not distract you from your creativity. The administrative effort should be kept as low as possible. When creating folder structures with the file manager, you can quickly become confused about where to sort an item. However, if you search using tags, you don’t even have this problem.

It is certainly not uncommon for individuals to use a folder structure and, through habit, find their way around it over time. However, as soon as a second person joins in, it becomes difficult. A lot of time is wasted on familiarization and searching. Not an ideal situation. With a folder-only system, there is a great risk that assets will not be sorted, but simply downloaded and unzipped. Elements that would actually belong in the same category can be found in different folders. Freelancers who are new to a studio then have to ask where to find which element. This means that at least two people are involved in a search. When ingesting new elements, Das Element indicates if an element already exists. This avoids duplication.

DP: And which tools in a VFX pipeline does it talk to?

Jonas Kluger: The nice thing about element is that you can actually use it with any software. It is a stand-alone software. No plug-ins are required to work with other applications.

On the one hand, you want to search your library and import the elements found into other software. To do this, you mark the selected elements in Das Element and can now drag and drop them into the desired application. The path to the main element is always used in the background. It does not really matter whether the path is an image sequence or perhaps a project file. The software with which you want to use Das Element will recognize this.

Of course, every software has different requirements, but this has also been taken into account. Let me give you an example using image sequences: In Nuke, I can drag and drop in the selected element and the image sequence will be imported. In Flame, however, a very special formatting of this path is necessary: (filename.[1001-1002].exr). This can be set in Das Element so that it fulfils the correct requirements in this case.

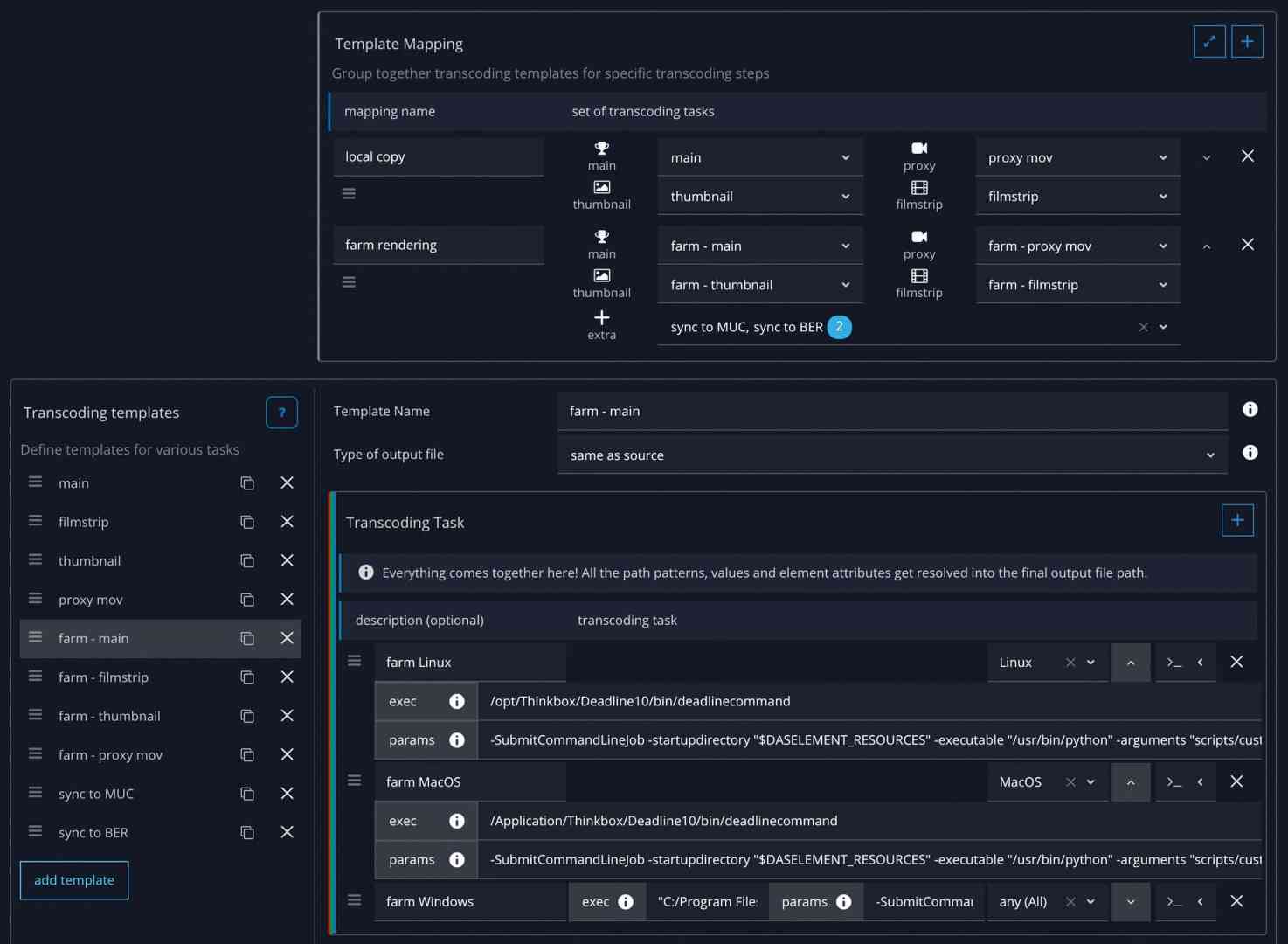

The second situation is the process of entering the elements into the library software and depends heavily on the respective needs of the user. These can include anything. A simple copy from A to B, a “leave my files where they are” to complex processes such as transcoding processes on the render farm to convert everything into an OpenEXR sequence with ACEScg Colourspace using Nuke, to then sync this with another location and its server and then perhaps create an entry in FTrack or Autodesk Shotgrid (formerly Shotgun).

If you need an even more extensive configuration, you can hook into certain places in the software at any time with your own scripts (so-called hooks). This makes it possible to use the respective API of another product. This allows you to create very powerful setups.

DP: What was it about the usual asset managers that bothered you so much that you developed your own?

Jonas Kluger: Anyone who has ever looked for library software for VFX will have realised that unfortunately there is no perfect solution for the requirements of the industry. Most of them can’t handle image sequences or the OpenEXR file format.

I have often seen in various VFX studios that software developed for another industry has been adapted to the VFX workflow by hook or by crook. Countless compromises were made in the process. Alternatively, larger studios have started to build their own solutions. These are very specifically adapted to their own needs and could possibly be optimized, because in my experience they often lack the resources to employ someone full-time.

I also didn’t quite like the license model of some asset managers. Either everything is in the cloud, which is not feasible in film and advertising production for data protection reasons, or you had to install a licence manually (node-locked) on each computer. This can be super annoying if you constantly have to worry about which version is installed on which computer. That’s why it was very important to me to use a similar license model to other VFX applications. You use a license server and only floating licenses, so it doesn’t matter which computer I’m on. I can open the element anywhere. This reduces the workload for IT enormously. An RLM server is used in the background, which has now become the industry standard.

It is also important to have an open system. You should have access to all data at all times. There are no proprietary formats or encrypted databases. All assets are available at all times, and the information in the database and configuration files is also created in common formats. This ensures that you still have access to the data, even if the license expires. As a technically experienced person, you can easily open the config files with a text editor, make changes and integrate them into a version management system such as Git or Perforce.

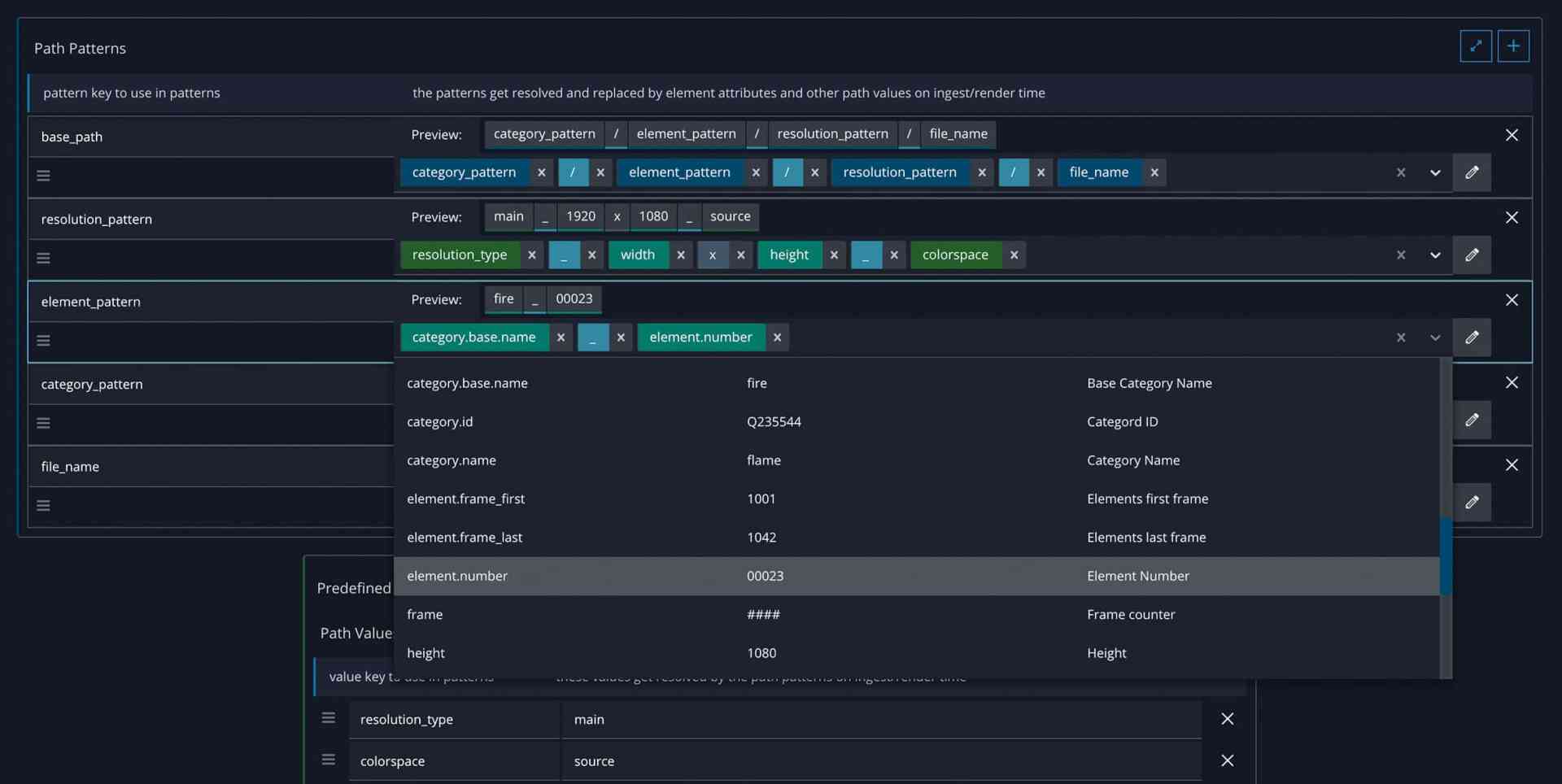

I have gone to great lengths to make the configuration of the folder structures and the transcoding task simple and visually appealing. On the one hand, it’s really fun to create your paths with Das Element’s Path Builder, and on the other, it takes a lot of work out of using the predefined structure and only having to overwrite values for the proxy formats, for example, in individual places. Other applications often make this process too technical and time-consuming. My approach is simple and intuitive with a fun factor.

DP: And all of this is already available?

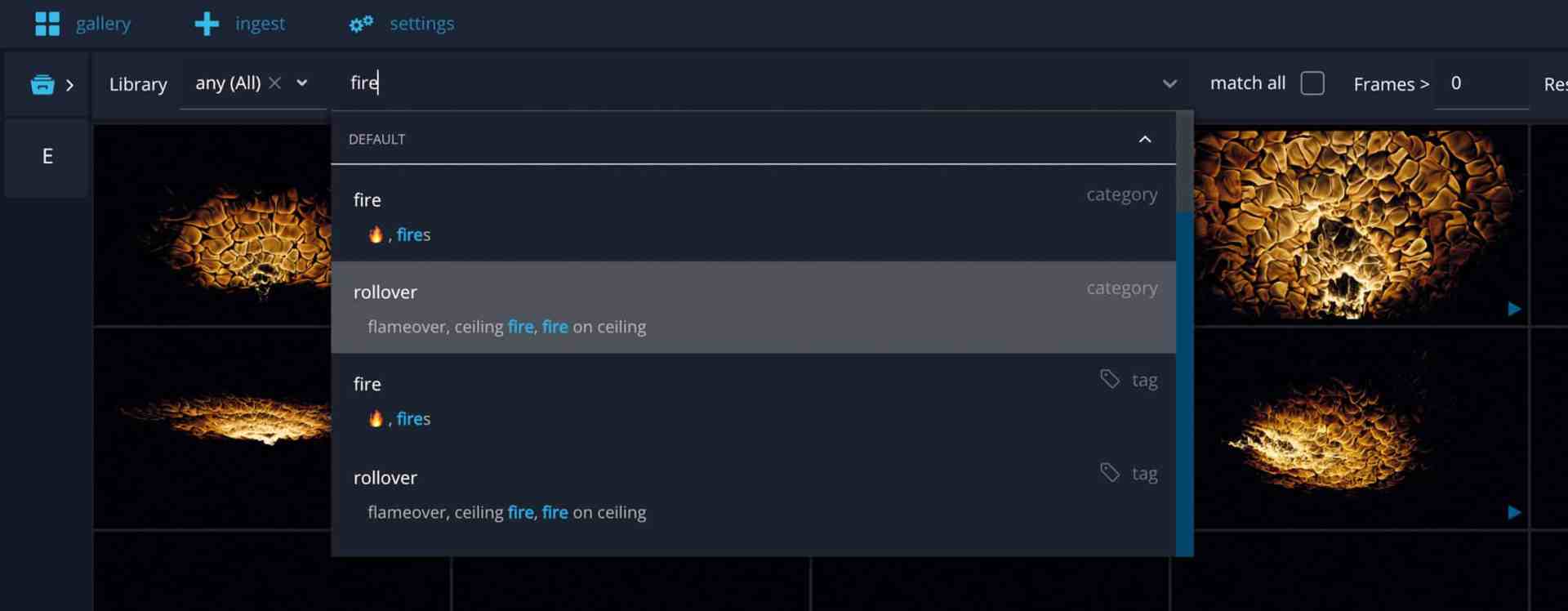

Jonas Kluger: Yes, exactly. With the help of the dynamic and visually appealing user interface and the gallery view, you can search for tags, categories or their synonyms and then simply drag and drop the elements found into the compositing software.

All elements are first added to the library using the ingest view. The auto-tagging function can be used here to automatically analyse image content and set tags.

With the out-of-the-box setting of the folder structure and proxy formats, you can set up a new library with just a few clicks. Many small details have been taken into consideration, e.g. the fact that preview images are always generated with a meaningful thumbnail or that the complete data can be moved to a new server at a later date.

You can configure the paths and transcoding processes at any time to customise everything to your own requirements. This also makes it possible to outsource the computationally intensive processes to a render farm. Any number of libraries can be created, either to organise a specific project or to share elements across different locations. The software works as a cross-platform and can be used on Linux, Windows and Mac OS operating systems.

There are a series of video tutorials on YouTube to help you get started with element and quickly learn and find your way around the software. They can also provide an insight into previously unused features.

DP: What can it do so far?

Jonas Kluger: With many filter options such as resolution or media format, you can quickly find what you are looking for. However, the software goes one step further. For each element there is information such as the original colour space and also the original path where the file was once located when it was added to the library.

I would like to mention a few less obvious features that have proved to be important over many years of working with asset libraries. A lot of emphasis is placed on productive day-to-day work. For each library, a field called “Library Root” is used to define where the actual data is located. The big advantage of this is that you can move the entire folder, e.g. to a new network storage location if you purchase a new server or want to copy the elements to another company location. A simple adjustment of this root directory is sufficient and all data is directly re-linked and found. This scenario happens more often than you might think, which is why element can handle it. In addition, a library can be used with different operating systems, as only the root path needs to be adapted.

The predefined naming convention and folder structure is a compromise between readability for the user on the file system and a long-lasting structure that allows you to change the category of an element at a later date without causing problems. There is nothing more annoying than opening old project files only to realize that a file no longer exists and you first have to find out where this file is now located or whether it has been renamed. With Das Element, a lot is solved via the database. This avoids such problems.

In addition, when new elements are added, it is also directly documented when which files with which tags were added. This is a simple CSV file that is saved with each ingest. On the one hand, this makes it possible to restore the status of the list at ingest with all tags and categories at any time. On the other hand, this is a good way to directly perform a batch import of many files. This history of imports is important for larger productions such as Fox Studios or Disney, which require such documentation. This kills several birds with one stone.

The software makes it possible to work with Python hook files. This means that tags are generated directly from the file name, metadata or other sources when importing elements. These can be specific keywords in the folder structure or file names, which are then generated directly during ingest.

DP: Can it be placed as a layer over existing structures?

Jonas Kluger: Absolutely! If there is an existing structure, it can be used without any problems. The naming convention, folder structure and all transcoding tasks are freely configurable. Scripts or other pipeline connections can also be adopted and reused. Existing tags and categories can also be imported.

For example, a VFX studio from Canada had already created an existing library including a category hierarchy tree in the XNView software. With a small script, all tags and the hierarchy tree could be customised directly. This made the move to element very smooth. The batch import was made possible with the aforementioned CSV files.

The minimum basic requirement of the software is that there are thumbnails for each element. All information is stored in a database so that you can work more effectively. For videos and image sequences, it is recommended to render a filmstrip. The entire clip is reduced to a length of around 24 frames. If you move the mouse over the preview, you can get a quick impression of the content of the sequence. This scrubbing feature is very helpful in the gallery view. That’s all you need.

DP: What exactly happens when new elements are added?

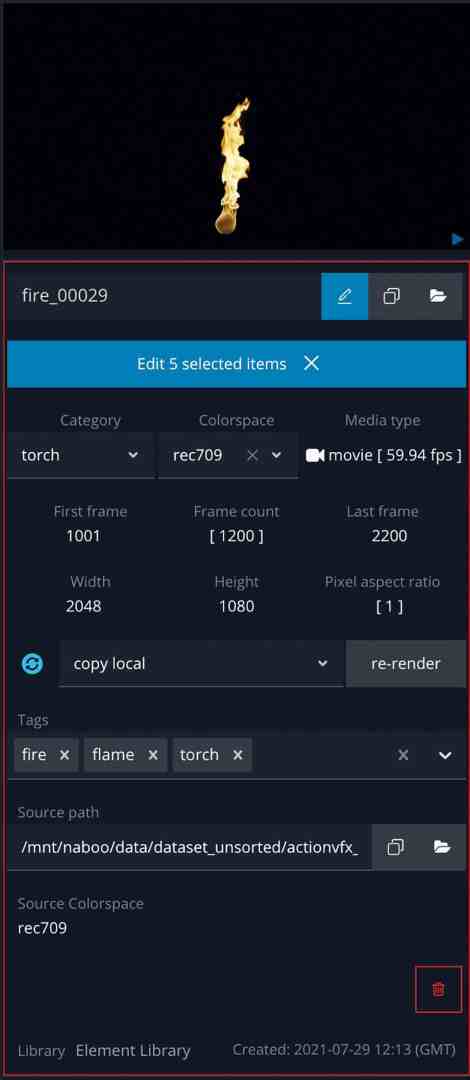

Jonas Kluger: A central function of the software is the ingesting of new elements. With the ingest view, you can easily add new elements to the already explained folder structure. With its extensive yet user-friendly user interface, element offers maximum control for tagging files.

Firstly, all elements are simply dragged and dropped into the ingest view of the software. A preview is created in each case so that you are visually supported during the subsequent tagging process. You assign a category to each element and can then assign tags as required.

Each new element goes through a series of transcoding steps that generate different preview formats. The software offers useful presets for thumbnail and proxy videos as well as film strips.

Existing in-house scripts can be used by running a custom command as a transcoding task. This means that you can also send everything to the render farm as a nuke job. The software offers various example scripts and you can download the latest version from a Git repository.

DP: What can be imported? And how much of it?

Jonas Kluger: The current main focus of Das Element on VFX and animation elements. This also covers a large proportion of the elements that can be obtained from various resources, whether from the customer or from a web shop.

The software processes various image formats and codecs. Whether videos from a DJI drone, clips from YouTube, Photoshop files, PDFs, HDRs or JPEG, TIFF, EXR or DPX sequences. All this and much more is possible. If you have older files such as Cineon (CIN), you can also manage them. The handling of camera raw formats such as ArriRaw and REDRaw is still limited at the moment. I would generally recommend developing and converting the files using the camera manufacturer’s software before adding them to a library. As soon as an EXR sequence has been rendered, for example, Das Element can then handle it perfectly.

How many elements can be imported depends entirely on the storage space on the company’s server. For the productive operation of larger libraries (I am talking about a few thousand elements here), it is recommended to use the PostGres database. This allows you to make several thousand requests per second. The database should therefore not be a bottleneck.

Due to the way the software is optimized in the background, a request is made to the database once at startup to get the information, whereupon everything is cached locally by the user as long as the software is open. This increases performance enormously when working, as information does not have to be constantly queried via the network. All that is loaded from the server are the thumbnails and any other proxy files. These are very small and allow you to work smoothly. If additional files are to be copied, this can be automated with a separate script.

DP: Can Das Element handle other sources (Studio Three location via network or a Dropbox folder in the middle of nowhere)?

Jonas Kluger: The software can handle this perfectly. A distinction is made internally between the high-res data and the preview files and metadata stored in the database. The database must be accessible for all participants. Where the preview files are located is not important for the software as long as the path is stored in the database. Whether the preview files are located on the server, in a shared folder that is automatically synchronized via the cloud (Dropbox, Google Drive or Microsoft OneDrive) or on a web server is simply a question of personal configuration.

One use case for the current home office situation is that an artist has a compressed library at home with only proxy files and a local database file or a database within the company that can be accessed via VPN.

Using the preview files, you can search through the elements and even try out proxy videos in the compositing software. The high-resolution data can then be requested from the company using the name of an element.

Alternatively, Das Elements can be stored on the company’s internal web server and users can access the thumbnails. In this way, the information can also be shared with multiple locations. If the high-res data is not available at one location, you can create a transcoding task that synchronizes everything to that location.

DP: And where do I define tags?

Jonas Kluger: Tags can be created at will, either when ingesting or editing an existing element. As soon as you start typing in the tags input field, all similar existing tags appear. There is an option to take an existing value or create a new tag. This prevents duplication of tags and unnecessary cluttering of the system.

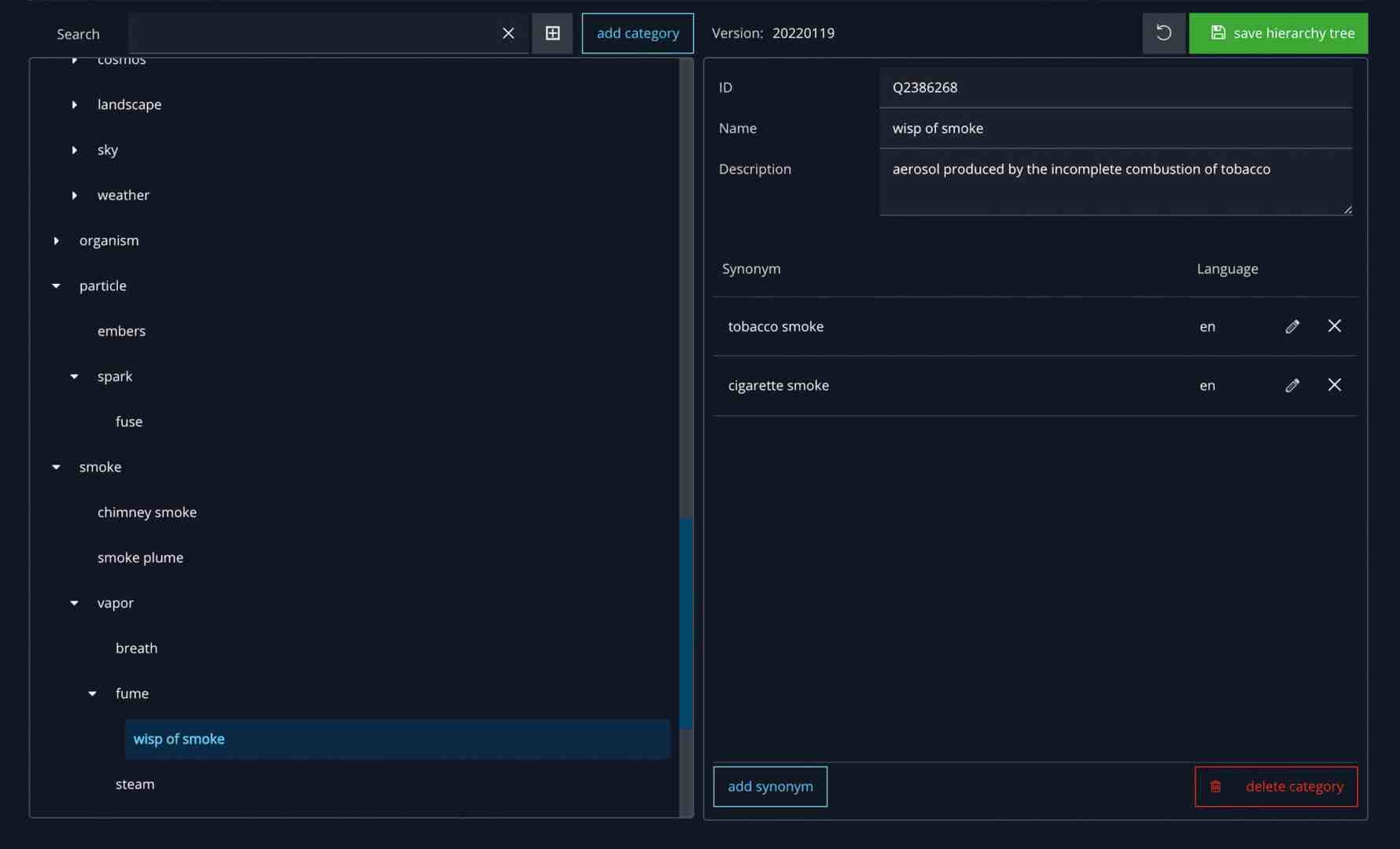

Categories can also be added or customized as required, as can synonyms. For tags that are likely to occur frequently, it is worth creating a separate category or using it as a synonym for an existing category.

How the tags are used can be determined very individually by a company. For example, it can be a project name or manufacturer of elements, but also a descriptive text such as “original plate” or “keyed element”. The design is completely free and left to the company or user. The only important thing is that an artist ultimately finds what they are looking for.

DP: To what extent are the tags customizable? Or can I customize the tags from other sources (spelling lists, metadata, etc.)?

Jonas Kluger: It is possible to have tags filled with a Python hook file directly when loading files into the ingest list. The file receives all paths that have been dragged and dropped onto the software, for example. You have the option of extracting information from the metadata of a file and, for example, generating a new tag with the focal length for this element. If a tag does not yet exist in the database, it is created automatically.

A fully functioning proof of concept was even created for a film team. The VFX team had the requirement to sort all elements for VFX directly on the film set after the shooting day. They proceeded as follows: There were different photo cameras for HDR shots, reference material or turntables of assets. The respective memory cards were copied to a predefined folder structure on a local network storage device on set. This was simply quicker and could be done by many people at the same time. The whole folder from one tag was then dragged onto Das Element, and the tags were all automatically created from the folder names. Now you just had to click on “Ingest” to create the thumbnails and enter all the information into the database.

The big advantage is that you can search for an asset name at any time and instantly find what was ever shot for that asset, regardless of the day of the shoot. If it is important which day the material was shot, this could be easily filtered out by adding the date.

DP: But how can I make sure that the artists find what they are looking for and don’t have to spend a long time searching for the right day?

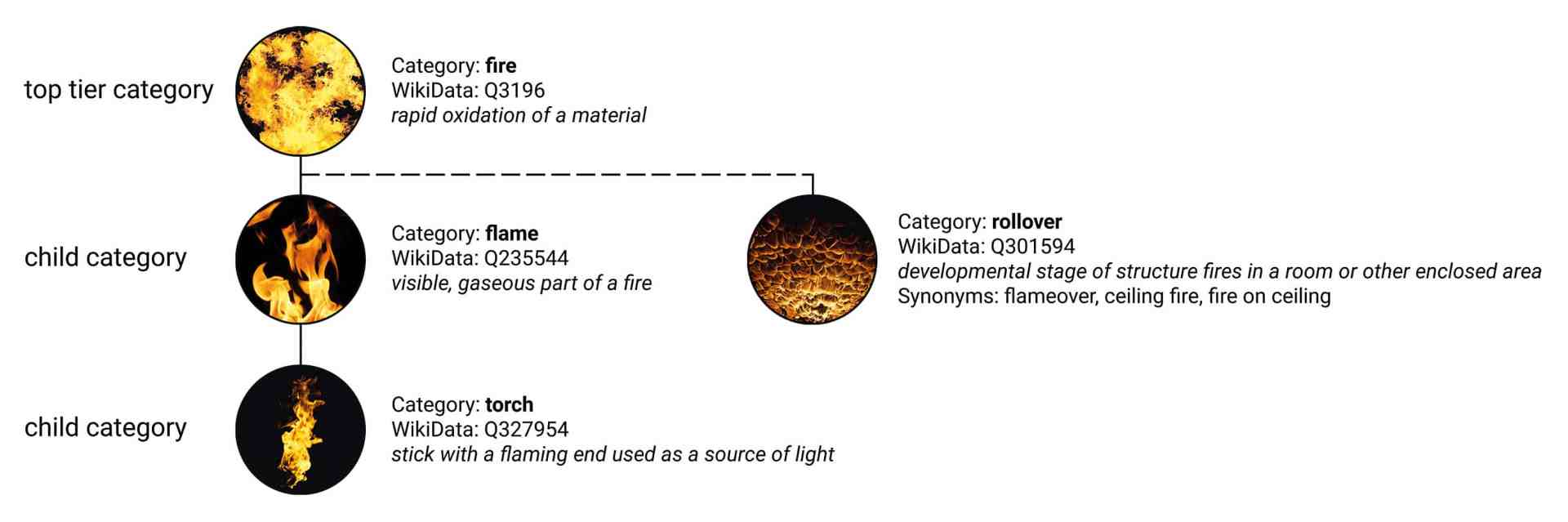

Jonas Kluger: The software comes with a well thought-out arrangement of categories in a hierarchical structure. A lot of time, energy and brainpower has gone into this. Users benefit from this well thought-out system.

Let’s take a look at an example of a torch element. As everyone probably has a rough idea of what element they are looking for, you can simply select the main category. In our case, “Fire”. The search can now be further refined using the hierarchy view. You might next select the “Flames” category, where you can directly see which elements are available in the respective subcategories. The search then continues to the “Torch” category, and here you will find what you are looking for without even knowing which tags were used during the search process.

The beauty of the VFX industry is that we come together from all parts of the world. With that in mind, Das Element focuses on finding a common vocabulary that unites all of our languages. The software uses descriptions and synonyms for each category from publicly available sources.

Wikidata IDs play an important role here. Behind every Wikipedia page is a specific Wikidata entry. The advantages of using data from this publicly accessible knowledge base are descriptive texts, synonyms and translations in different languages.

Since each category can be linked to an exact Wikidata page, we can standardize a common understanding and vocabulary of what a particular category is called. No matter where you come from or what language you speak, this approach should make it easier to find the perfect element.

For example, the categories “fume” (smoke) and “wisp of smoke” (cigarette smoke) are often confused. This is where the machine learning model helps, because it can analys exactly how these two categories differ visually.

DP: But I can then use the tags in the search, or can you find more uses for them?

Jonas Kluger: You have to differentiate between categories, tags and a third type, the wildcards. The idea of tags is that you can use them in numerous ways to describe an element as precisely as possible. Categories, on the other hand, are there to give a name to a specific grouping of elements. A category is therefore something more permanent.

For example, you can include the category name or a category ID in the file or folder name in order to recognize exactly what it is on the file system. Whether an element can be seen on the left or right of the image is more likely to be clarified via a tag. If the image is mirrored or rotated in the software, this parameter would otherwise no longer be correct if it had been written in the file name.

The third type, wildcards, are placeholders for parameters that are dependent on the individual elements. The software analyses each element carefully before it is entered. Values such as the resolution or file format, the first and last frame for image sequences and the codec or frame rate for videos are entered. These are also values that can be used to describe the element.

They can be filtered in the gallery view, for example to search for the minimum length of an element. These element-dependent parameters can be used in the settings and the naming convention to act as a kind of placeholder. They are also called wildcards.

As we only know the resolution of an element when we ingest it, we need these placeholders to define our folder name structure in advance. The actual parameters only become known during ingestion, the wildcard is resolved and replaced with the correct values. This is how the final file path is created.

As a user, I have access to a wide variety of values here, which can be helpful. If you want to execute a user-defined command line command, these wildcards are extremely helpful and can be used to pass on various values to other scripts or programs.

DP: So Das Element sorts all my Studio assets and makes them searchable with tags. But how does it decide which keyword is suitable for which file?

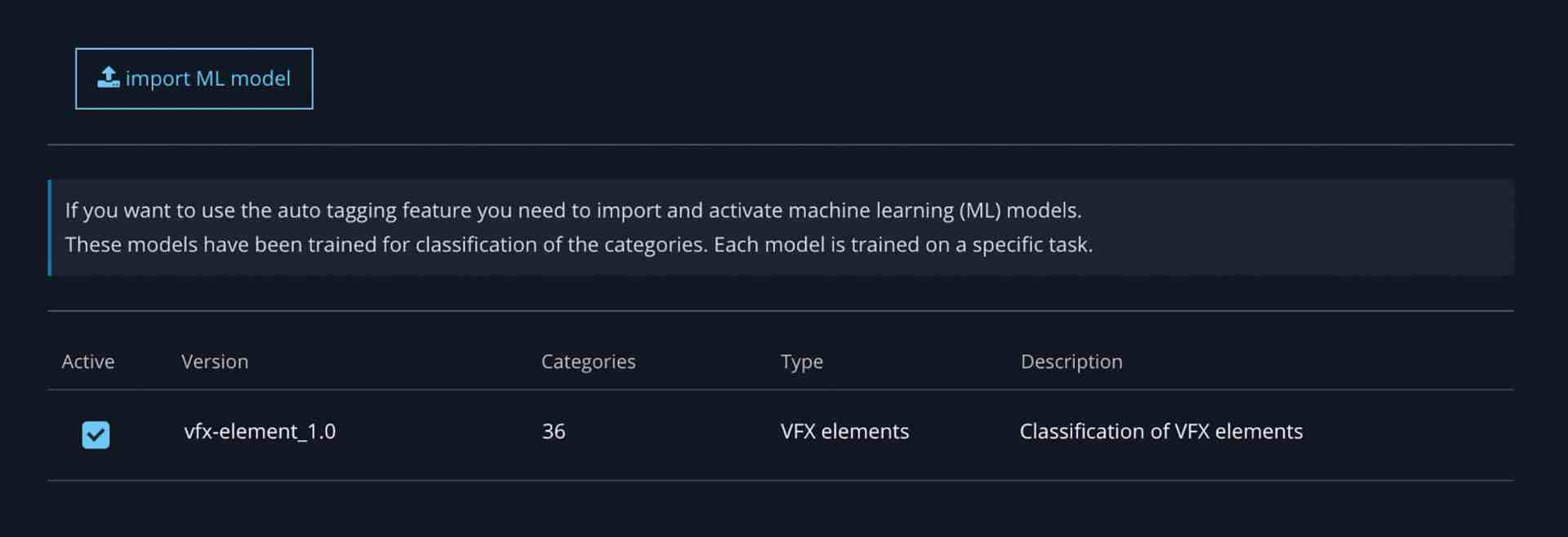

Jonas Kluger: The data can be analyzed by users using auto tagging before it is ingested in order to find the best possible tags and tag them automatically. This works with a machine learning model from Das Element that has been specially trained with thousands of VFX elements.

Most services on the market that offer AI use a model type in the background that is based on a very specific data set of images. This is usually the ImageNet Challenge; a collection of countless images divided into 1,000 categories. This is a benchmark training set that can be used to compare how well a type of neural network performs. The advantage lies in the large number of categories with everyday objects, animals or similar. However, if you search for a specific word, e.g. “fire”, you only get a few suitable categories, such as fire grate for a fireplace or campfire, a fire boat or fire engine and the fire salamander. Of course, this is not particularly helpful for professional work with visual effects.

That’s why I decided to create my own training data set. I have been continuously expanding this collection for 3 years now. I have bought all kinds of element libraries that can be found on the Internet and feed them into the training set. One major difficulty, however, is finding enough data points, i.e. images or videos. For the search terms “fire”, “flame” etc. you get countless material. For footage of nuclear explosions on a black background or VFX portal effects, it is more difficult to find enough different image material. For classification with machine learning, you need a different and varied selection for a category so that you can easily differentiate it from an obvious other category.

If I can’t find enough elements for a category on the Internet, then I take a few photos of glowing coals at a family barbecue, or if I notice a container on the street with rubble and debris that are nicely arranged from the perspective of a VFX artist, I take out my mobile phone to constantly expand the data set. All images and videos are sorted and tagged by hand to achieve the best possible result. A machine learning model, a convolutional neural network, is then trained and passed to the users of the software.

As soon as elements are added to the library, a second machine learning model is trained in the background. This model is based on existing elements in the library. The more elements are added, the better it gets. In the ingest view, you receive suggestions as to which category it could probably be. The idea is to develop an independent model that can be trained on any category as long as there are enough training samples. As the library grows, the model becomes more accurate.

DP: And if I have assets that are not recognizable in your sorting?

Jonas Kluger: The auto-tagging feature can be a great help with many elements. However, I still recommend a manual check to add further keywords that the model does not yet recognize, for example, and to add further characteristics such as speed or size. These characteristics can be rather subjective under certain circumstances.

The technology used for machine learning models is comparatively new, although the theory behind it has been around for a very long time. It can happen that the model either does not recognize a category and therefore does not enter a value, or it mistakenly thinks that it is some random other category. In this case, however, the user quickly realises that the tag supplied makes no sense and removes it. Of course, you can always edit the existing library in the gallery view if you notice something that is incorrectly tagged during a search.

It is recommended that you always briefly double-check each element, regardless of auto-tagging. Every element should be tagged correctly at least once before it is added to the library. After all, that’s what the input process is for.

DP: Where will Das Element go from here?

Jonas Kluger: In order to make the software even more accessible from the outside, a Python API is to be added. This has been put on the back burner for various reasons. I am curious to see how the whole topic of Python 3 will develop in the VFX industry.

There are also plans to set up a marketplace where you can search not only your own elements, but also all libraries from element providers on the Internet. This makes it possible to buy individual elements, add them automatically and thus expand your own library with elements that are needed for the current task.

A web view of the software is also conceivable for the future, so that you can log in via a browser. Perhaps even a cloud solution for freelancers so that they always have online access to all the references they have ever collected.

DP: What other features are available?

Jonas Kluger: We are planning some tidying up in the background, a kind of spring-cleaning for the software. Stability is much more important to me than lots of new features that don’t really work. A library is a long-lasting thing that should exist and function for years. When I talk to users, they often still have files from the last millennium in PAL that are still in use.

One particular innovation that is on the immediate to-do list is an improvement to the rating and voting system for elements, which analyses the most popular elements in the background. In addition, the option is to be created to rate elements of poor quality so that they slide further into the background. A few users have requested this change and I would like to fulfil this request.

A playlist system will be introduced to strengthen team collaboration. This means that a team lead can put together a collection of suitable elements in advance and distribute them to all artists in a kind of playlist. This means that not everyone has to search through various libraries individually, but already has, for example, the top 20 fire elements that are suitable for a sequence or setting. The playlist system can save an enormous amount of time and promotes collaboration within the team.

Other file formats such as project files or setups for Nuke or After Effects will also be supported. These can also be very helpful if you want to reuse a rain or noise setup several times. The project file is ingested into the library and a preview image can then be added so that you can see at a glance what is happening in this script.

DP: What other new features are planned in the long term?

Jonas Kluger: A lot is planned and conceivable for the future. However, the community is an important decision-maker. Nobody can say which requirements are particularly important better than those who use the software on a daily basis and thus recognize and pass on useful suggestions for improvement in the course of their work. After all, the software was (or is) programmed for specific users and not for someone who has thought about something in a quiet room but can’t relate it to reality. I welcome creative suggestions and an open dialogue. OCIO (OpenColorIO) is to be integrated for better colour management.

DP: Where can you get Das Element if you want to try it out?

Jonas Kluger: If you want to find out more about Das Element and see it in action, you can make an appointment for a live demo at any time via the website. To do this, you select an available date and time from a calendar. You will then receive a confirmation email and a Zoom link.

I personally take a lot of time to present the software during the appointment and discuss all questions and use cases. If you want to try out the software straight away, you will find an e-mail address on the website where you can request a 30-day trial version. The trial version offers the full scope, you can test the software extensively and learn to love it. If you have any other questions or suggestions, please do not hesitate to contact me. I am very interested in optimizing Das Element for everyone.

![a group of people in various poses with a focus on a woman in white attire overlayed with the text switchx and the tagline switch anything keep what matters the scene is set against a beach background at dusk digital production A group of people in various poses, with a focus on a woman in white attire, overlayed with the text 'SWITCHX' and the tagline 'SWITCH [ANYTHING]. KEEP WHAT MATTERS.' The scene is set against a beach background at dusk.](https://i0.wp.com/digitalproduction.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/beeble-switchx-hero.png?resize=110%2C110&quality=72&ssl=1)