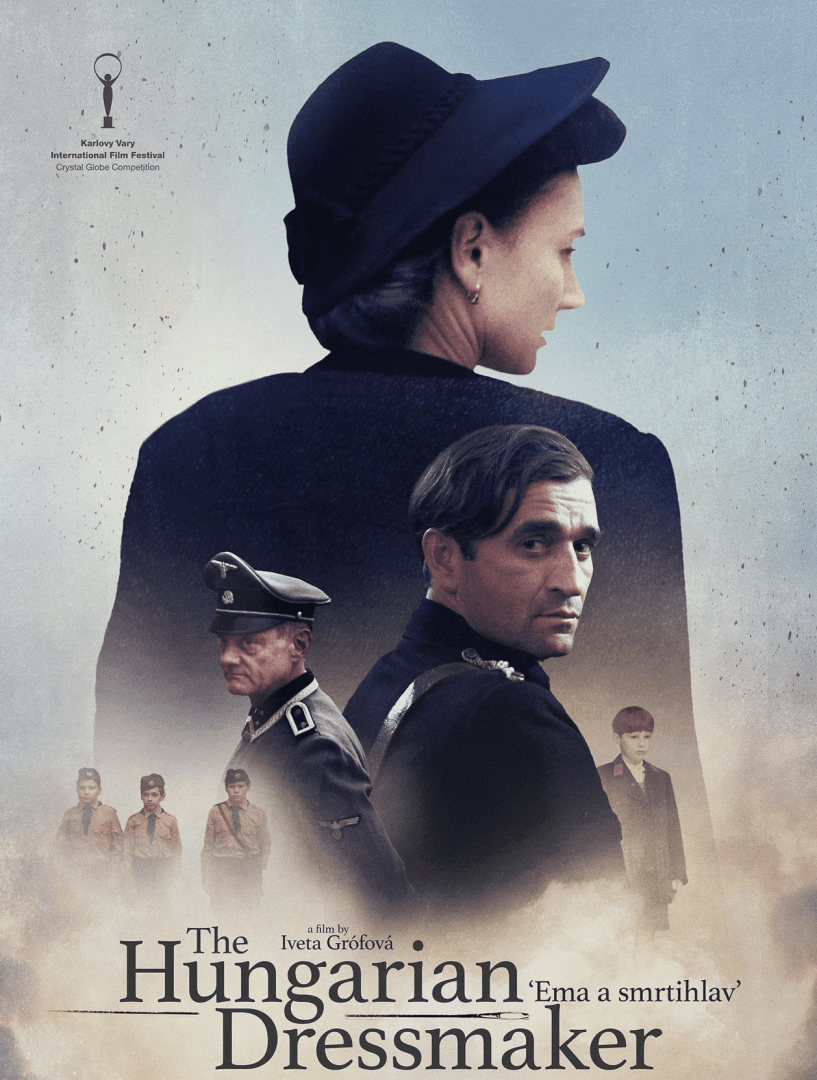

When The Hungarian Dressmaker was selected as Slovakia’s submission for the 2024 Academy Awards, it wasn’t just a win for the country’s film scene—it was also a showcase of what Central Europe’s VFX talent can achieve under pressure. For PFX, the Prague-headquartered post-production powerhouse with offices across six countries, the project was a chance to push its in-house pipeline and cross-border workflow to new heights.

We spoke with Tibor Meliš (VFX Supervisor) and Tomáš Srovnal (VFX and Post-production Producer) about recreating wartime Bratislava in pixels, managing crowds and chaos with procedural logic, lighting bus scenes with LED walls, and what happens when a cornfield refuses to catch fire at 5 AM. Spoiler: compositing wins.

DP: What was your initial reaction to being selected as Slovakia’s Oscar entry, and how did this impact your approach to the VFX work?

Tibor Meliš: I was very happy about it. This film was a very exciting journey, as the creative core of the production was in constant contact with us, which allowed us to fully express ourselves.

DP: Your team worked across multiple offices. How did you ensure consistency in visual quality and technical approach across such a distributed pipeline?

Tibor Meliš: Our main management tool is Ftrack, to which we have developed our own engine that drives the pace :) and brings logic and structure, while communicating with all the software we use in-house. Additionally, for leadership and supervision, we have our own internal software, which is a very important tool for daily reviews, giving feedback, and also for bidding – it’s really excellent. :)

(Comment: We are working with PFX on a seprate story for that tool – stay tuned!)

DP: How did you structure asset creation and shot tracking to maintain efficiency while meeting the film’s tight deadlines?

Tibor Meliš: Shot and asset production ran in parallel, organized by sequences. Compositors focused on the straightforward shots with no heavy dependencies while tracking and asset teams built the necessary elements in the background. We broke down environments into modular kits—facades, props, street elements—and versioned them heavily in Ftrack. Assets were linked directly to scenes, so when an updated version was dropped in, it automatically propagated. That saved us tons of time and enabled rapid iteration across sequences.

Furthermore, as I mentioned earlier, we have our own software that allows us to track shot continuity with excellent quality and near-instant response. That means when an artist changes something for review, it appears on the timeline within a second, and we can immediately compare multiple shots or versions.

DP: PFX is known for supporting productions that utilize tax incentives. Did this play a role in The Hungarian Dressmaker?

Tomáš Srovnal: We generally support all projects regardless of size or method of financing. By providing services across six Central European countries, we help producers in situations where a project needs to be completed in a specific country due to local spend requirements. This was also the case for this film. However, since it was a Slovak production, finishing the project through our Slovak office was naturally the first preferred choice for multiple reasons.

DP: What lessons or innovations from this project will influence your future work at PFX?

Tibor Meliš: One of the most interesting challenges was working with LED walls for the bus sequence. The technology is amazing—it can create incredibly immersive lighting and reflections in-camera—but it also demands a shift in production thinking. Not every director or DOP is fully ready for that yet. It requires decisiveness, and often that’s at odds with the natural desire to leave options open for post.

We ran into that too, but we made the most of it. We used the LED walls to generate interactive reflections and flickering light across the actors’ faces. We built a forest scene in Unreal Engine and placed the LEDs at an angle, so they not only lit the scene but also complemented the greenscreens visible through the bus windows. That kind of real-time content and lighting interaction is something we’re definitely bringing forward into other projects, but we need to be weary of the potential issues. Sometimes a simple green screen is less costly and a better option, mostly when you are working with less experienced or prepared on-set teams.

Apart from that during this project, we really deepened our collaboration with the grading and mastering department. While we were finalizing VFX shots, the grading team was already progressing in parallel. We kept a tight feedback loop, sharing updates frequently to make sure the VFX work aligned with the DOP’s vision and the overall tone of the grade. To make the process smoother, we developed custom scripts for DaVinci Resolve that automatically synced in the latest VFX versions and allowed for batch uploading of EXRs directly to the Barrandov office. We also tested a color pipeline to synchronize our Resolve workflow with their Baselight environment, which helped maintain consistency across departments and avoid surprises in the final master.

DP: Recreating 1940s Bratislava required detailed architecture and period accuracy. How did your team approach building the digital environments, and what were the key steps in your pipeline?

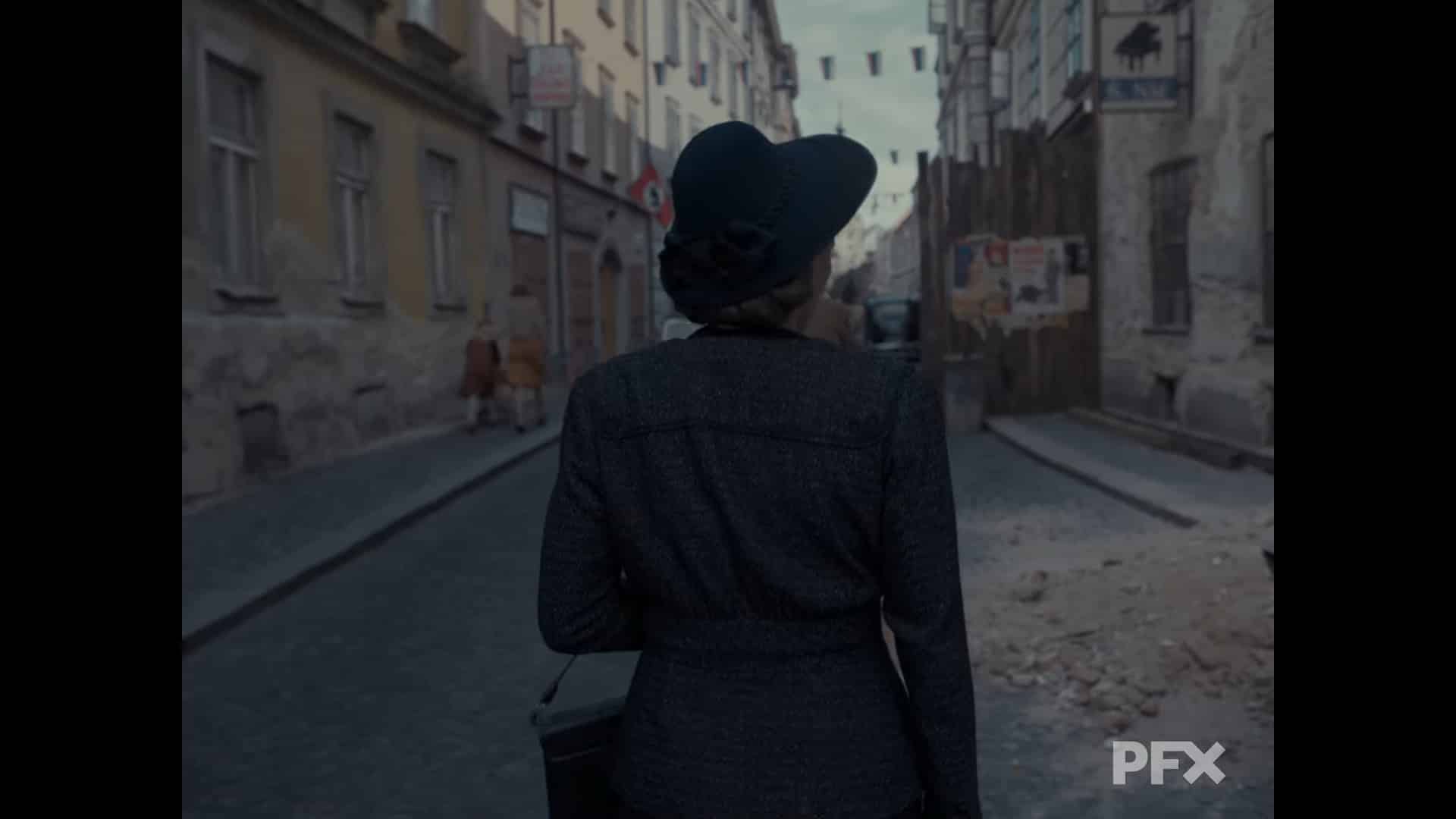

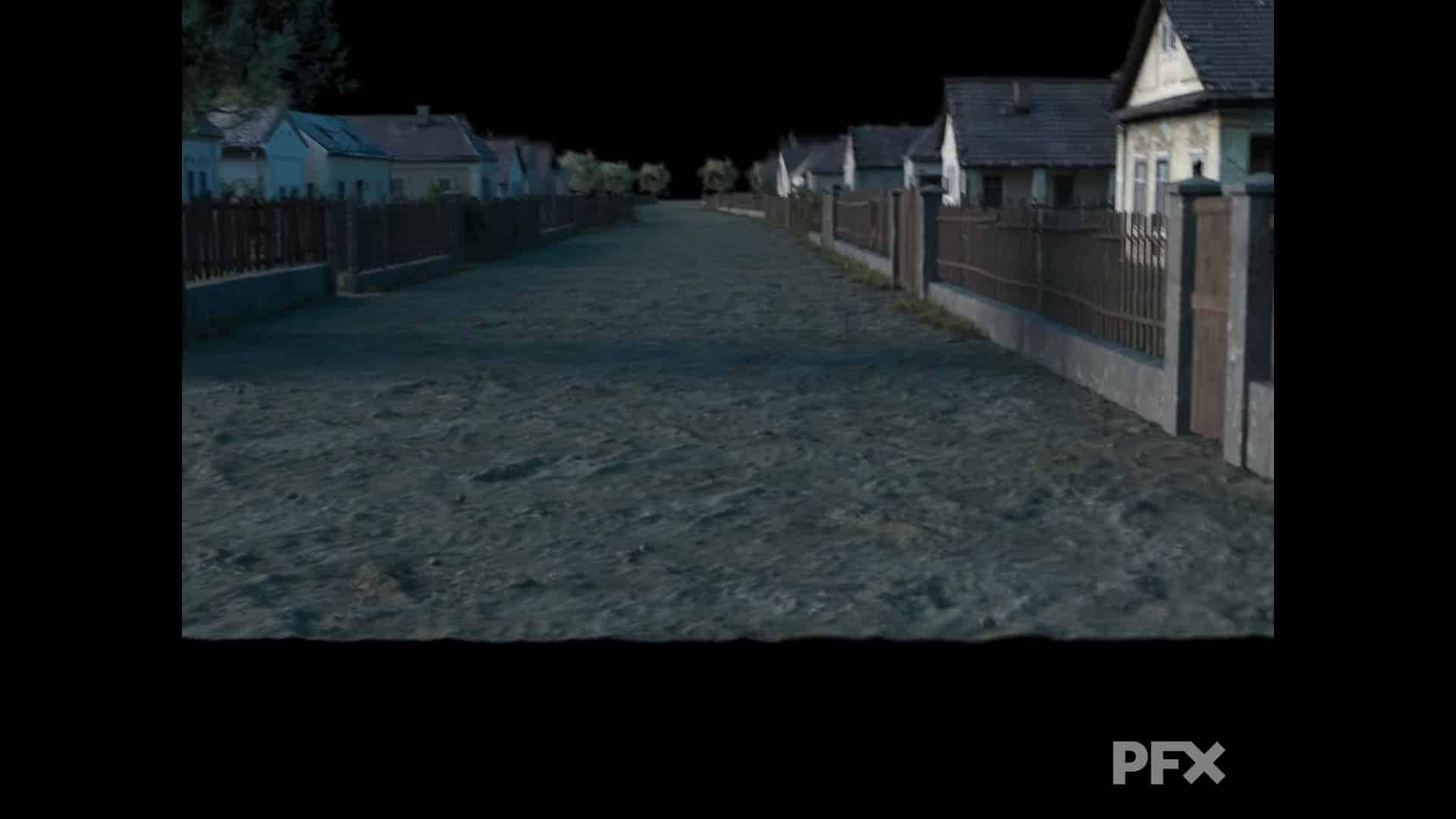

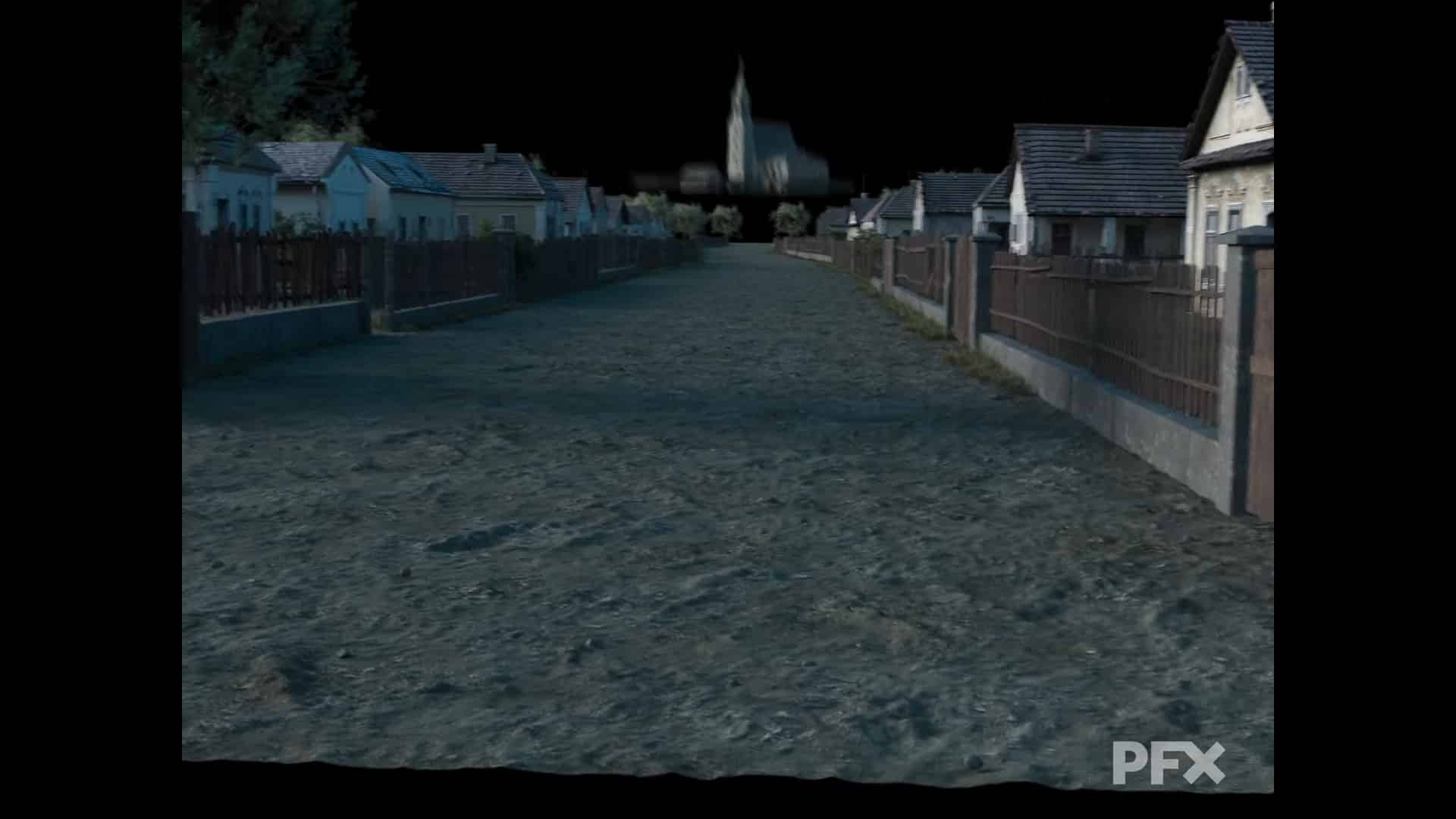

Tibor Meliš: The first step was detailed research. The director already had a large collection of references from archives, covering buildings, houses, and streets. Biskupice was particularly specific because several nationalities lived there, something many Slovaks today can’t even imagine. It was a village near Bratislava (today it’s part of the city) right on the Hungarian border, so naturally there were strong Hungarian and German influences.

We created around ten types of house assets with porches (“gánok”) and carefully studied the environment, as the porches were built mainly to shade from the sun, depending on the sun’s trajectory. Since the porches were a key visual element we wanted to emphasize, we had to adapt the lighting conditions to place them correctly relative to the camera.

The material was shot after sunset, which gave a very soft light, so the cinematographer had to lower the aperture, creating a shallow depth of field. We simulated clouds to pass the sunlight intermittently, keeping the protagonist in the shade while illuminating the houses in the background as if during daytime.

In compositing, we animated the cloud movement using P_noise to make the transition between sunlit and shaded areas feel natural. This approach also helped us highlight the Church of St. Nicholas in the distance, a landmark important to Biskupice. When viewers watch the shot, their gaze naturally moves from the actress’s face toward the brightest point – the church.

DP: Crowd simulation was a significant part of the project. Which tools or techniques did you use for this, and how did you manage the interactions between digital extras and the environment?

Tibor Meliš: Crowds are one of our long-term trademarks. Thanks to previous projects, we already had a pretty extensive internal library of Houdini-based 3D agents from this exact historical period—and already animated. So for The Hungarian Dressmaker, we just adapted and extended them to fit the new sequences. That saved us a lot of time on both modeling and rigging.

DP: The fire sequence features a long, intricate shot. Could you walk us through the preparation process for this sequence, from previsualization to final compositing?

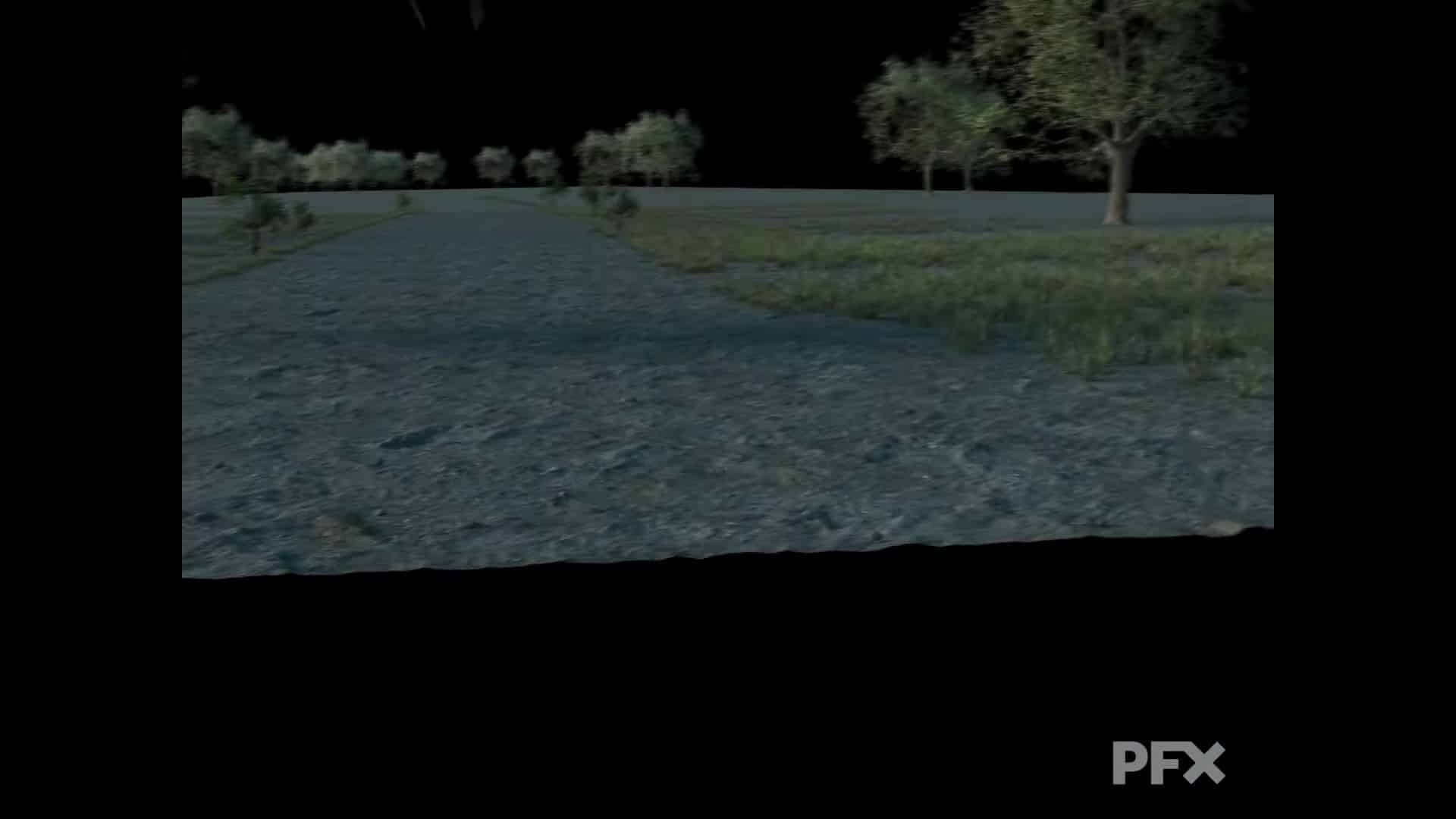

Tibor Meliš: I would start with the production plan: we intended to create a real, controlled fire that would cover a significant part of the frame. We also had the SFX team ready to create fire elements in the third plane to help us integrate everything later.

When working with fire in a realistic film, I always try to create an atmosphere on set with smoke and strong flickering light sources that we can later match in post-production. This scene was truly massive, and since it was meant to be filmed in a single take, it became even more challenging. Unfortunately, the plan to set the cornfield ablaze in the background failed. The sequence was shot around 5 AM as the sun was rising, so we had to capture what we could, and the rest was left for post-production.

DP: The fire sequence was one of the most challenging. How did your pipeline handle simulations for such long shots, and what solutions were critical for maintaining realism without compromising render times?

Tibor Meliš: We initially planned for a lot of FX team support for this shot.

When I got the first rough cut, I started developing a preliminary lookdev myself, focusing on the timing and creating the best reference for the FX team using ActionVFX footage. Since the scene’s dramaturgy involved the fire gradually growing while the camera interacted with it, this approach seemed the quickest.

After the first version, I was surprised at how well it worked. I requested an additional burning tree asset in the background from the FX team because many objects felt too static, and with so much heat buildup, there should have been turbulence affecting twigs and grass. In Nuke, I projected the cornfield and added multiple light sources parented to the light intensity of the VFX footage, integrating them into the scene. The beauty of the shot is that when you look at such a strong light source, you must also feel it in the camera — most objects were slightly desaturated and softened, and the added mist between the actors provided great integration. In the end, a significant part of the scene was built through compositing.

DP: Do you have any recommendations for VFX artists preparing similar large-scale fire scenes?

Tibor Meliš: Definitely create smoke on set and shine light through it to achieve that strong luminous component. This will make it easier for the camera to capture the atmosphere and will greatly assist in post-production, whether for masking or optical effects.

Always think ahead – you can easily blend the luminous layer later based on your CG or footage fire. Lighting on set is absolutely crucial. Nowadays, creating fire digitally isn’t difficult, but making it match real set lighting perfectly – that’s the real challenge.

DP: What role did procedural workflows play in creating wear, grime, and historical imperfections in the digital assets?

Tibor Meliš: Procedural workflows played a key role in depicting wear, dirt, and imperfections in digital assets, especially in shader creation. They enabled the automated generation of realistic effects such as chipped edges, scratches, dust, and patina, giving objects an aged and well-used appearance.

This approach significantly accelerated and streamlined the texturing process and the creation of variations, while ensuring consistency and a sufficient level of detail. The workflow involved the use of various types of noise patterns and the consideration of convex and concave shapes of the assets, which allowed for the combination and layering of materials to achieve the desired look.

DP: How did you balance “dirty realism” – the lived-in look of the city – with the polished historical aesthetics required by the story?

Tibor Meliš: On Ventúrska Street, there’s a moment when someone in a CG building gently opens a window, creating a glare into the camera. These are the little moments that bring a space to life. And if you noticed, I intentionally wrote “someone” to further enhance that feeling of life. In reality, it was just the animated window. :)

DP: The film integrates subtle details like flags, uniforms, and street decor. How were these assets designed and implemented into the final shots?

Tibor Meliš: These kinds of details—like flags, signs, posters, or other ambient decor—are crucial for immersion. We knew this period would require a lot of specific details, like the banners carried by groups of people on the street. We carefully selected what reflected the society at that time and used it as inspiration for asset creation. For example, in the opening scene on Ventúrska Street, the hustle and bustle are enhanced by a parade of children pushing baby carriages, which is also edited within the shot.

When looking down either end of the street, we had to work with the crowd to make sure it wasn’t too aggressive but complemented the parade atmosphere. Most of them were Houdini-based procedural elements that helped break the static feel of the scenes, creating natural motion and realism.

DP: Achieving historical authenticity often means working with incomplete or limited references. Do you have any tips for sourcing high-quality references for similar historical projects?

Tibor Meliš: Definitely consult the city library of the relevant city. We relied heavily on archival materials!

The Hungarian Dressmaker

Director: Iveta Grofova

Producer: Zuzana Mistríková, Ondřej Trojan

DOP: Martin Strba

PFX Team

VFX Supervisor: Tibor Meliš

VFX and Post-production Producer: Tomáš Srovnal

Grading: Tomáš Chudomel

About PFX

PFX is a full-service post-production studio operating across the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, and Germany. With over 250 talented artists, they provided services to film, TV, animation, and commercial creators for well over a decade.

PFX.tv

instagram.com/pfxcompany/

facebook.com/PFXcompany/

x.com/pfxcompany

youtube.com/pfx

linkedin.com/pfx-company/

vimeo.com/pfxcompany/