Table of Contents Show

When I opened the TD Meetup 21, I asked a simple question: “Why talk about virtual reality again?”

A few years ago VR was everywhere – headsets, conferences, demos, hype – but it quietly faded into the background when projects stalled and the novelty wore off. At the same time, I’ve seen steady progress: VR now serves as a practical, cost-saving tool for architecture, design, visualisation and increasingly for our industry of VFX and animation.

I recall first meeting Dan Franke (Instagram) at the FMX 2025, where his VR artworks reignited my interest. His work in Quill VR showed that virtual reality can be more than a viewing device; it can be a creative environment. For previsualisation, VR allows directors and supervisors to plan set extensions and camera movement directly inside a 3D world. For artists, it allows sculpting and painting in a space that feels natural, intuitive, and immediate and for audiences, it redefines immersion, especially in documentary or experiential content such as the Fukushima 360° recordings. My goal for the evening was to let Dan demonstrate that potential in action and to remind our technical community that VR is not gone – it has simply grown up.

Who Is Dan Franke – From Student to VR Pioneer

Dan traced his path from his days as a CG generalist sculpting aliens in ZBrush, to discovering his passion for direction and storytelling. During his studies at the Animationsinstitut, he created a 2D short film that confirmed his interest in animation. Later, as a co-director on the children’s series Petzi at Studio Soi, he learned the realities of production management and communication. Dan described that time with a laugh: “I was a student with imposter syndrome, surrounded by world-class animators, suddenly telling them what to do.”

That experience taught him not only humility but also efficiency. Big projects require coordination, teams, and budgets – luxuries students rarely have. So he began searching for tools that could give him independence, something that let a small team or even a single artist, produce complex animation on their own terms.

The Moment Dan Discovered Quill

Dan’s turning point came when he discovered Quill, then being developed at Oculus Story Studio by Goro Fujita and Inigo Quilez. The tool allowed painting and animating directly in 3D space inside VR. When he saw early demos of artists sketching in volumetric space, he realised he needed to try it.

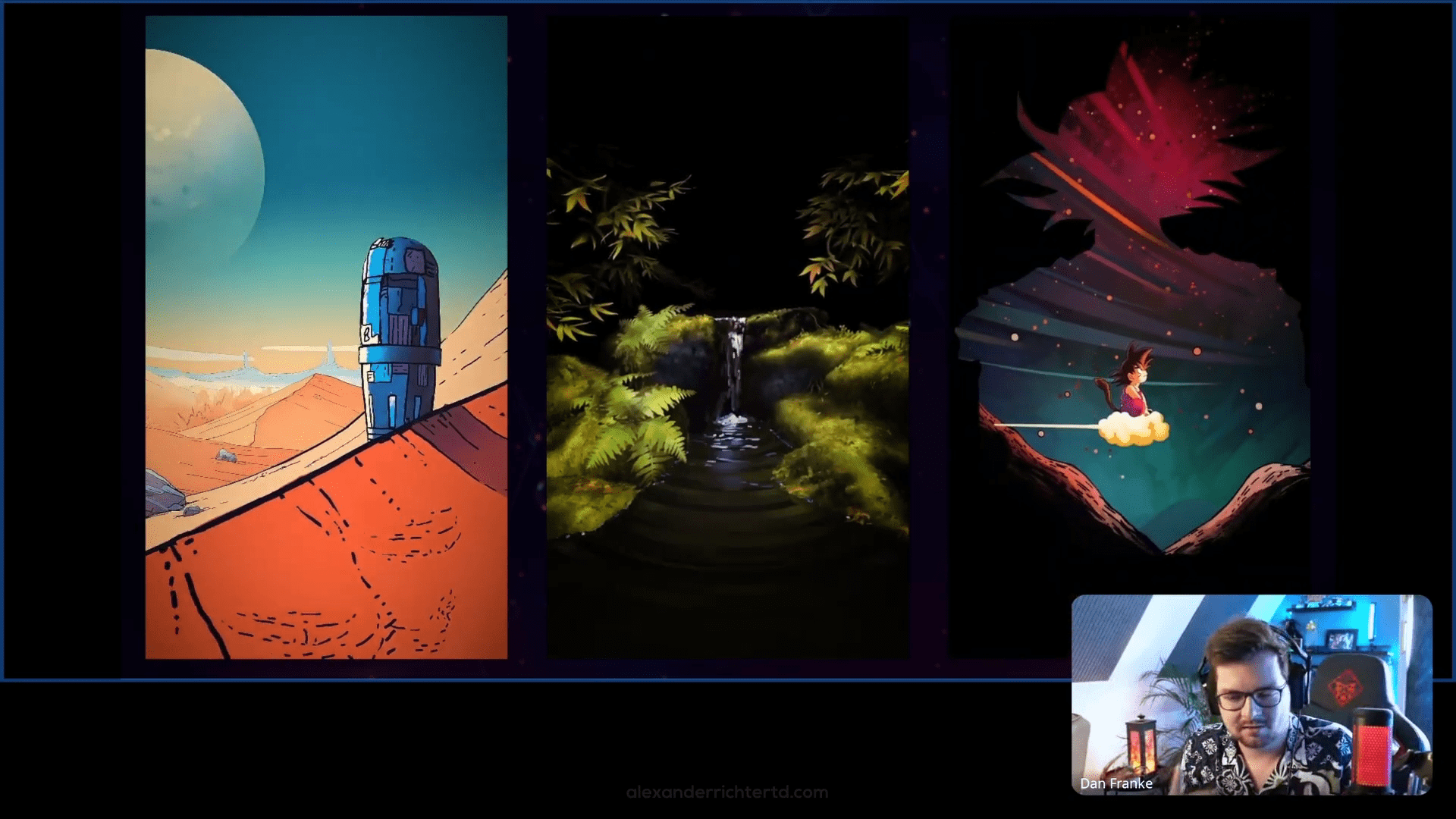

By coincidence, only a week later Goro came to Dan’s university for the first public Quill workshop. Within two days Dan had learned the basics. One day later he produced his first 3D painting entirely in Quill. He described the revelation: Quill is essentially Photoshop in three dimensions, where you can paint brush strokes that exist in space and then animate them in real time.

Because the Quill community was small at the time, Dan’s early experiments quickly gained attention on Facebook groups and later on Discord. That visibility led to collaborations on major VR projects, connecting him to studios and other artists pushing the same frontier.

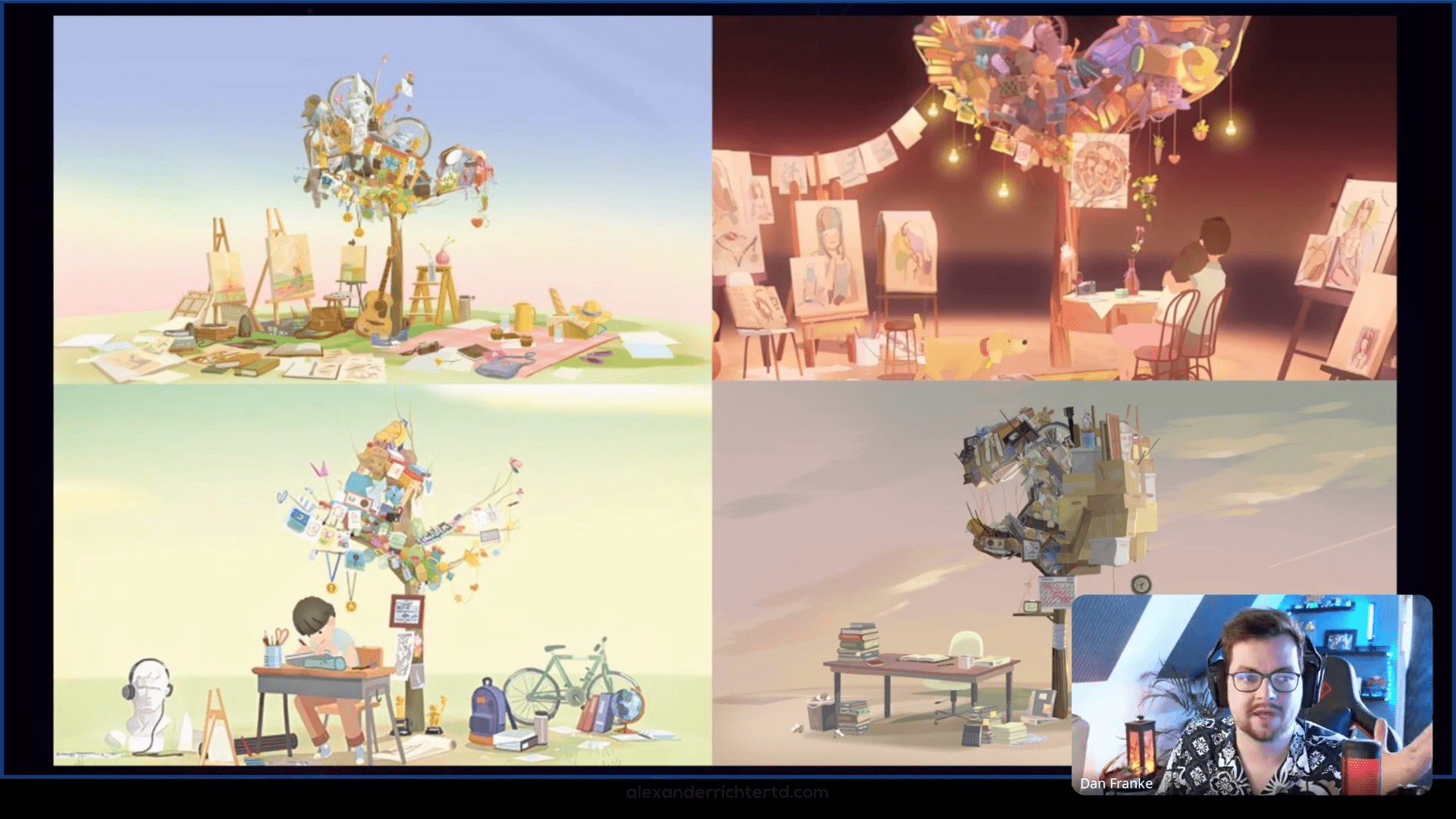

Early Projects: Namoo, Tales from Soda Island and Studio Syro

One of Dan’s first significant productions was Namoo, directed by Oscar-nominated filmmaker Eric O. The piece, both a VR experience and a 2D short, was built by a small team that included former Pixar and Disney artists. Dan’s contribution was painting and animating the environments entirely in Quill. Every tree, branch, and memory sequence in Namoo was handcrafted in volumetric brush strokes rather than traditional geometry.

After Namoo, Dan and a collective of Quill artists pitched an experimental concept to Meta: a world built of music, colour, and tiny creatures, inspired by the label Soda Island. Meta funded the idea, and Tales from Soda Island became the first full VR series created entirely in VR. The group formed Studio Syro (Instagram), a distributed studio that operated remotely during the pandemic and didn’t meet physically until years later.

Dan directed the first three of seven episodes, each more technically ambitious than the last. In the beginning, he still thought in 2D, using storyboards and fixed “cameras.” By the second episode, moving through full 360° space, he realised that traditional storyboarding didn’t fit VR storytelling. He had to adapt.

He recalled following Einstein’s quote: “Everyone knew it was impossible until a fool who didn’t know came along and just did it.” Dan chose to ignore established VR conventions and invented his own film language by borrowing timing and rhythm from 2D cinema but applying them in a 3D world.

As production evolved, Studio Syro discovered that Quill could replace much of the previsualisation pipeline. They began creating layouts, camera moves, and storyboards directly in VR. The approach combined storyboarding, animatic, and previs in a single tool, accelerating iteration and improving communication across the team.

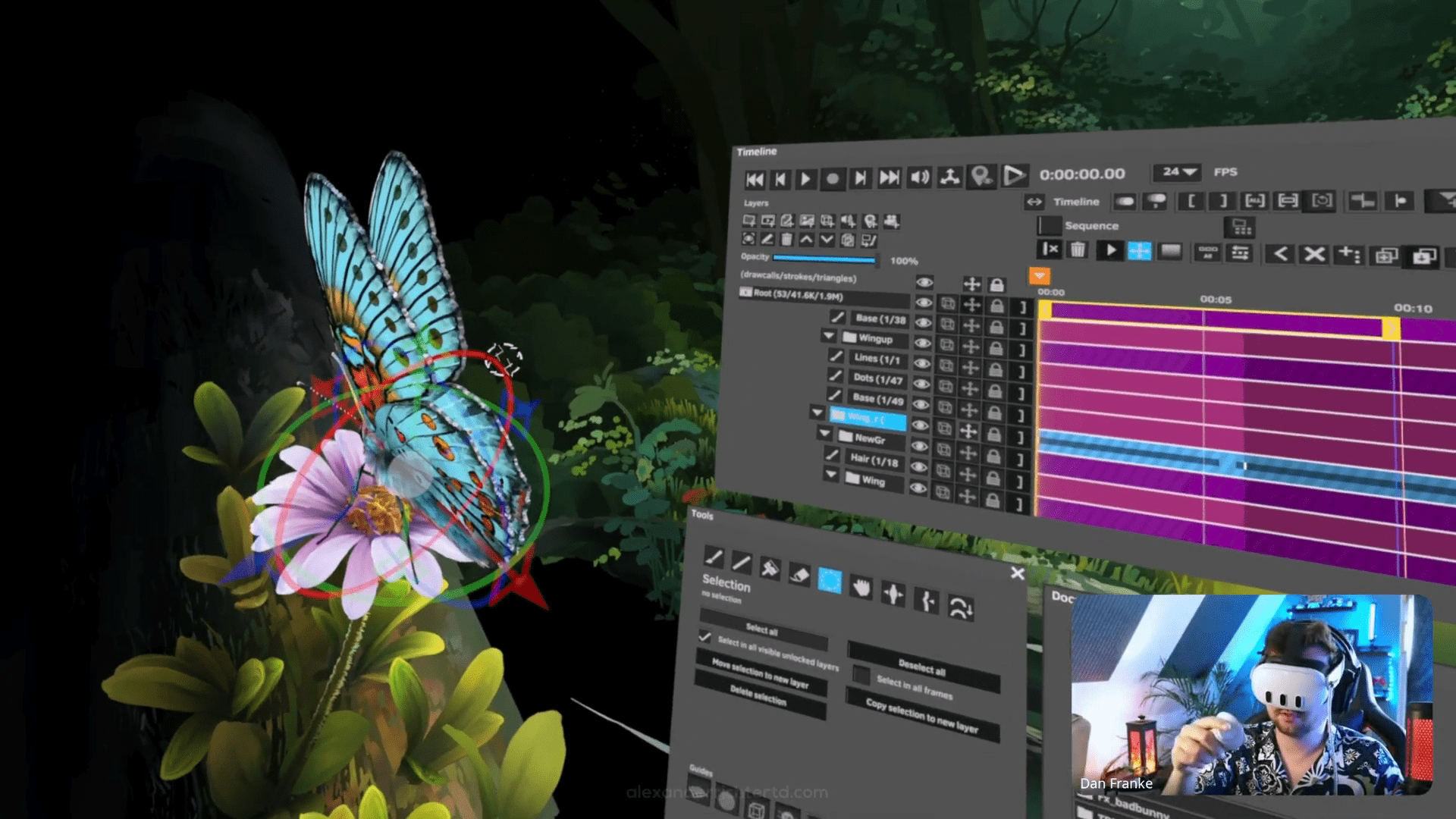

Quill Techniques in Practice

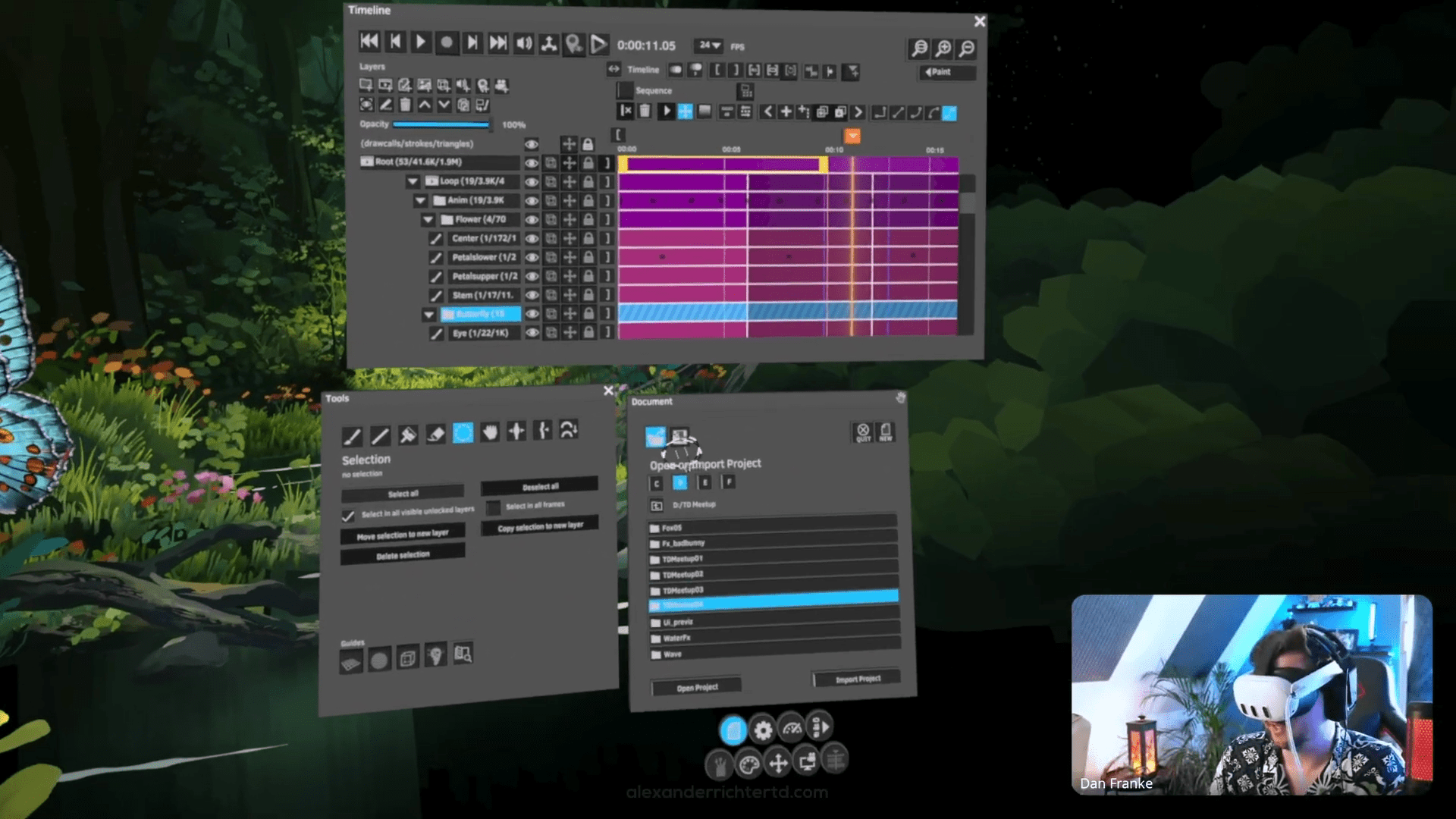

When Dan switched to live demonstration mode during the meetup, the chat went silent. We all watched a butterfly appear in front of him – a cloud of brush strokes grouped into parts. He grabbed one wing by its pivot, moved it in real time and Quill recorded the motion. There was no rig, no keyframes, no constraints. Just his hand and the headset tracking every nuance.

He explained that the technique relies on simple grouping and pivot placement: Once you define the hinge point, you can record your hand motions as animation data. The result looks organic because it is organic. Human motion captured directly as a brush movement.

“I animate the wing by grabbing it and rotating it in real time. No rig involved – just grouping and recording my hand motion.”

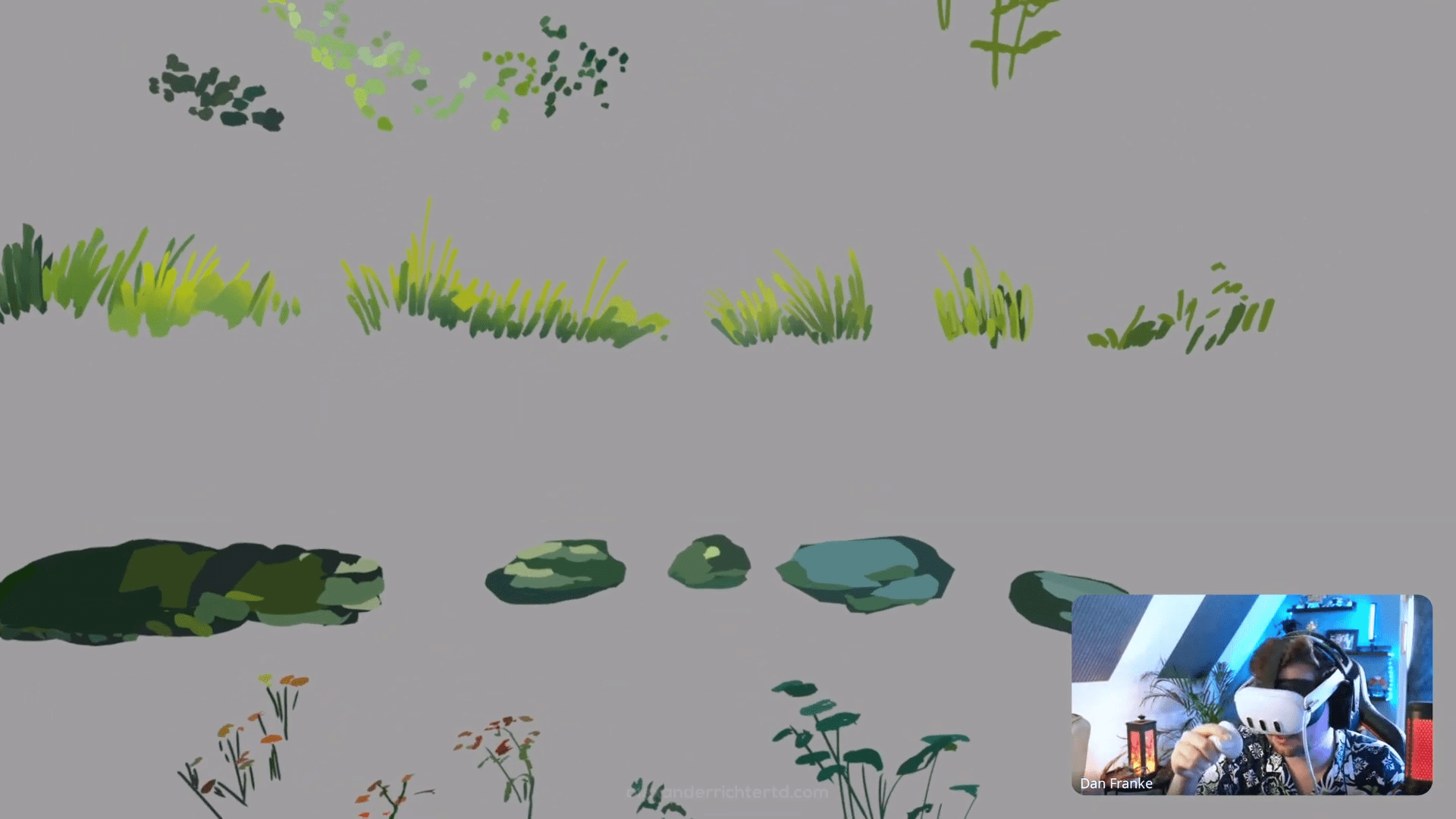

In another scene, he built a stylised water effect: Creating an empty layer, looping frames, painting fluid motion stroke by stroke and using the grab tool to distort the surface. He described how easy it was to “make it rain” in Quill by simply painting downward strokes and looping them.

Later, he opened visuals from a project for music artist Bad Bunny, showing psychedelic stage graphics created entirely with painted animations in Quill. Clouds, waves, and surreal textures moved fluidly, achieved by layering and distorting rotating spheres and painted strokes. Watching him deform shapes live felt closer to sculpting clay than editing polygons.

Dan emphasised that Quill rewards improvisation. You paint one small detail, duplicate it, rearrange it and soon the space fills into a world. It’s procedural, but handmade. An artist’s version of Houdini logic.

Quill as Previsualisation Tool

To show how Quill functions as a previs system, Dan built a miniature tunnel scene from scratch. He painted simple grey strokes to form walls and ceiling, duplicated them for depth, then added colour and placed a camera. A rough character shape followed; a black silhouette with a stick weapon.

He then activated record mode, grabbed the character, and moved it through the space while looking through the camera view. The animation was recorded instantly. Within seconds, he had a readable scene: The character walks forward, pauses, then reacts to falling rocks that he painted in next. The result looked crude yet expressive enough to read the motion, staging and timing.

Dan pointed out that such iterations would normally require drawing, editing, compositing, and re-timing across several programs. In Quill, it happens in one continuous creative act. That immediacy, he argued, shortens iteration loops and encourages experimentation.

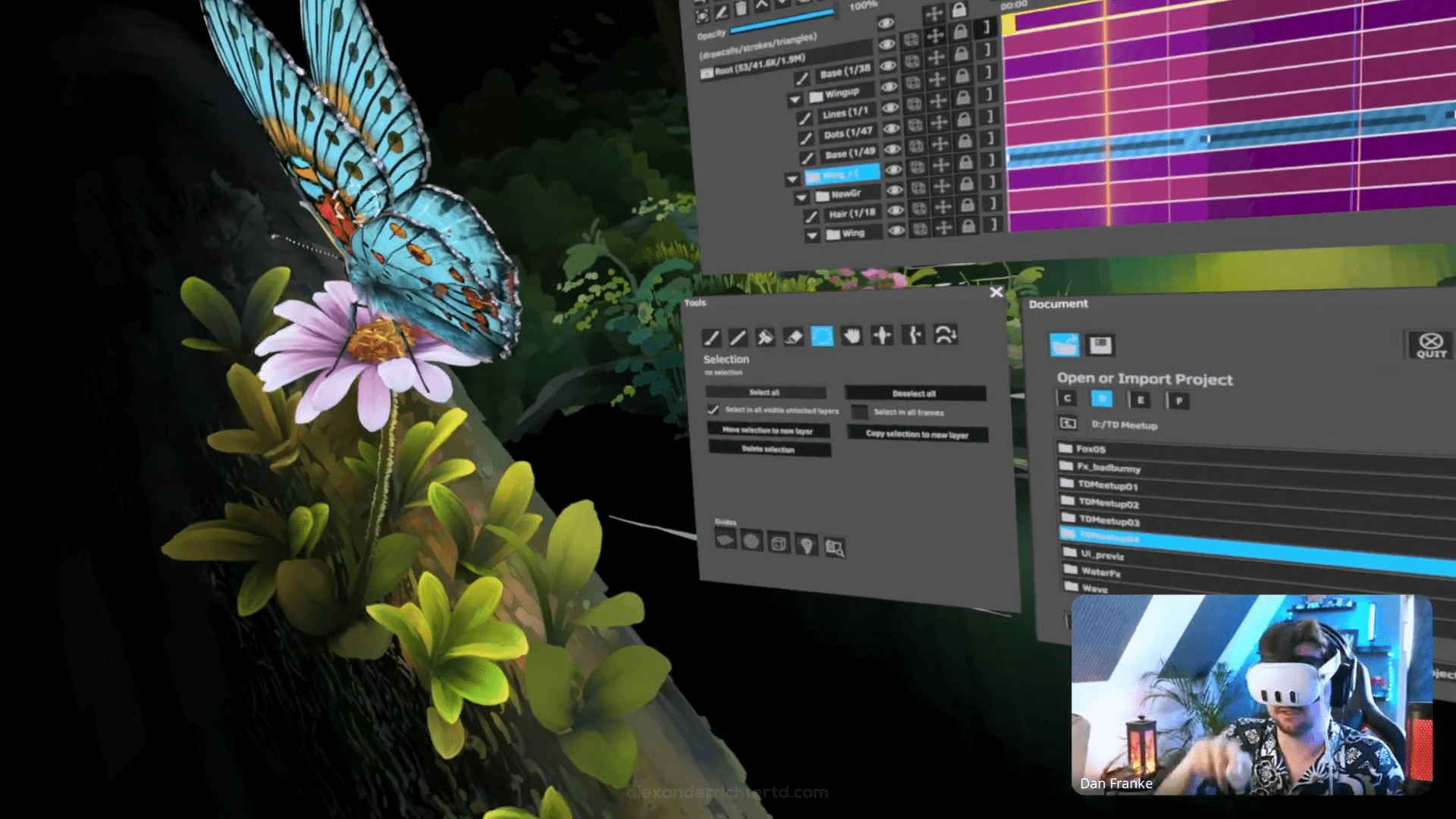

Integrating Quill into the Pipeline

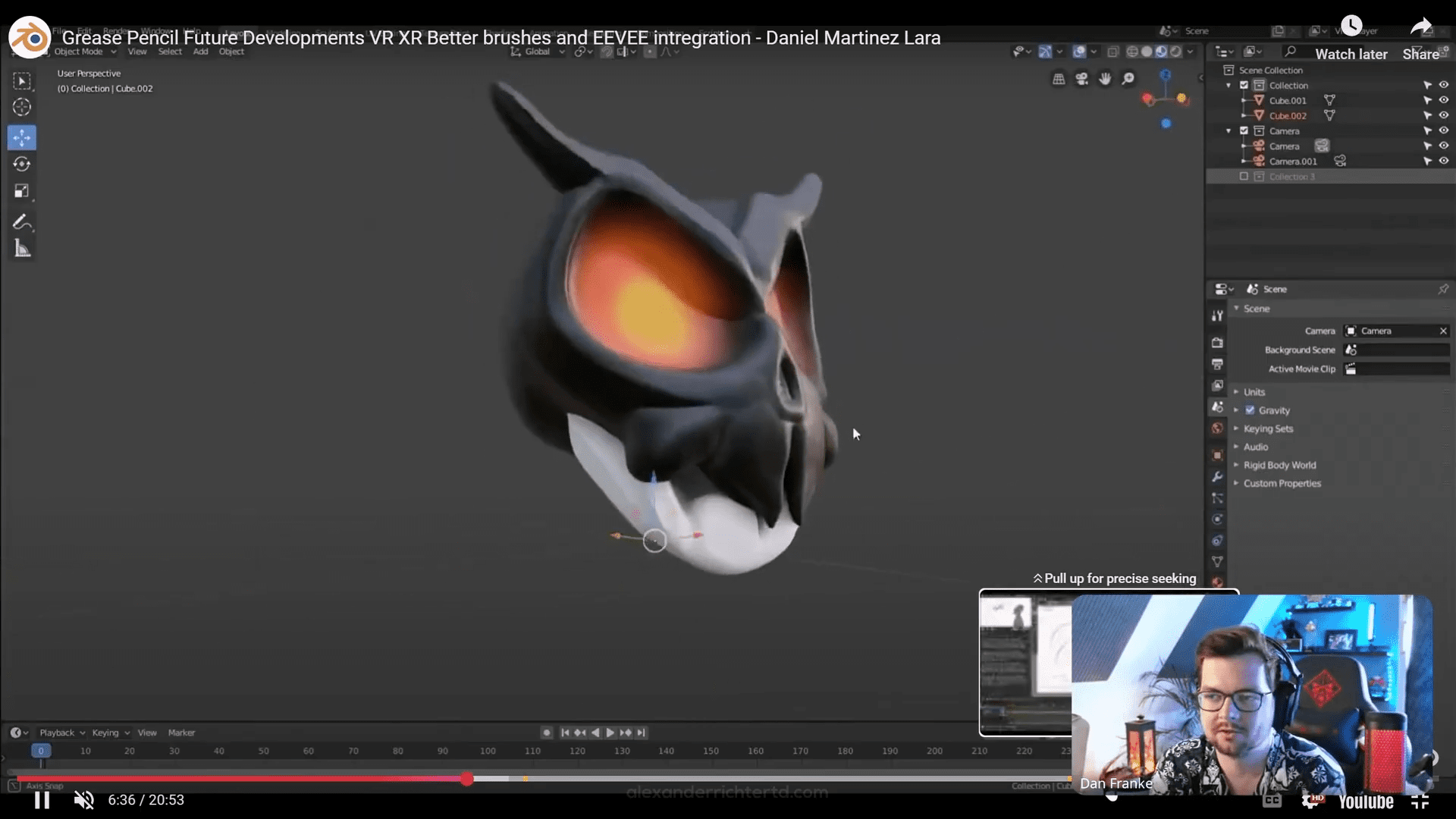

After the demos, Dan addressed a question many TDs were waiting for: How does this fit into existing pipelines? Quill, he explained, can export geometry and animation as FBX, OBJ, or Alembic files. Those can be imported into Maya, Blender or Houdini. Because Quill’s geometry is built from individual brush strokes, the surfaces are not watertight meshes; lighting them directly reveals visible edges. For that reason, Quill output is best used for stylised effects, abstract backgrounds, or reference geometry rather than production models.

Nevertheless, it can serve as an excellent art-direction tool. Effects departments can import Quill volumes as timing and motion references or even as collision shapes for simulations. Dan also mentioned upcoming work on integrating Quill-like tools into Blender via the new Grease Pencil VR prototype. Such integration could make these workflows accessible to more artists and, importantly, open to scripting and extensions.

I added that this is precisely where technical directors come in. New tools often lack the surrounding infrastructure: exporters, optimisers, render bridges. A TD’s role is to evaluate these technologies, write the missing connectors, and make them usable for the rest of the team.

Audience Q&A Highlights

When the Q&A opened, the questions came quickly. One attendee asked how long he can work in VR before fatigue sets in. Dan said it varies widely between people. During his workshops, newcomers sometimes need a day to adjust, but he personally can work ten to twelve hours in Quill without issue. Early in his career he trained himself by playing VR flight games, performing barrel rolls to eliminate motion sickness. Then he laughed and admitted he once fell asleep wearing the headset and woke up still inside the virtual space – a surreal experience he does not recommend.

Another participant asked whether Quill supports painting over live video. Dan explained that you can import footage as layers, remove alpha channels, and paint directly over them. His Arcane reel used this method: He filmed his hands on green screen, composited the footage inside Quill and drew the environment around it.

A third question concerned hardware. Dan recommended Meta Quest headsets, specifically the Quest 2, 3, or lightweight 3S, as ideal for Quill. Even older Oculus Rifts still function, though with poorer optics. He added that Quill runs smoothly on mid-range PCs or even laptops; high-end GPUs are not mandatory.

Finally, someone asked how technical Quill is to operate. Dan described it as “the least technical software I’ve ever used.” With only a few controller buttons to memorise, the barrier to entry is low. Within two days of workshops, most students forget the buttons entirely and focus on creation. But integrating Quill into a production pipeline is another story: Depending on project complexity, a studio may need an import/export script, shaders or performance tools. He recommended that TDs interested in supporting Quill learn basic Python scripting to build these bridges.

Quill in Production Contexts

At that point I asked Dan to imagine returning to Petzi and directing a new season. Would he use Quill purely for previs or even for final output? He replied that for Petsy, Quill would excel in the early stages like storyboarding, layout, animatic, and camera blocking. The advantage lies in speed: Directors can test ideas directly without waiting for new drawings.

For final production, Quill could contribute stylised effects like smoke, rain, splashes, painterly transitions but likely not main characters. The stroke-based meshes show seams under realistic lighting. However, he added that exporting animated Quill volumes as Alembic can serve as perfect guides for effects artists, giving them a timed and shaped reference for further simulation.

I agreed. Productions often struggle to communicate tone and feeling from 2D concept to 3D execution. VR sketching bridges that gap by letting everyone see and feel scale, movement and atmosphere directly. A line drawing leaves room for interpretation; a spatial sketch shows intent.

Reflections and Takeaways

After nearly two hours of live painting, animation, and discussion, I took a step back. Watching Dan work made it clear that Quill sits at a fascinating intersection of art and technology. It reintroduces immediacy to digital production: The artist’s gesture becomes motion, not data entry.

The implications for production are tangible. In early design and previs, VR tools can compress the time between idea and validation. A director or TD can sketch in space, test pacing, iterate on blocking and hand off to layout or animation without traditional bottlenecks.

Equally important, these tools demand new types of collaboration. Technical artists need to connect them to render pipelines, while creatives need to understand what they can ask from them. Quill proves that the two roles of artist and technologist are no longer separate worlds but overlapping disciplines.

What’s Next and How to Join

TD Meetup continues monthly. The next session will tackle Python Challenges, focusing on automation and problem-solving for real production pipelines. If you would like to join future events, visit td-meetup and register. Recordings of previous sessions, including Dan’s full Quill demo, are available on the TD Meetup YouTube playlist.

Dan’s VR Painting Foundations Course is available at vrpaintingcourse.com, where he teaches Quill basics and advanced VR animation techniques. For those wanting to experiment, Quill itself can be found at quill.art, and Meta Quest (Facebook-Login Required?) hardware details are listed at meta.com.

Final Thoughts

The TD Meetup 21 reminded us that VR is far from dead. Tools like Quill demonstrate that immersive creation is not a gimmick but a workflow accelerator. Dan Franke’s live session showed how real-time painting and animation can merge art, direction, and technical design into one fluid process.

As we move into an era dominated by AI tools, his closing comment resonated: VR remains the most human form of digital creation. It captures not the machine’s interpretation, but the artist’s hand. Watching him animate by literally waving his hand in the air, I thought: This is where technology feels alive again.

See you at the next Meetup,

Alex