We see virtual production stages everywhere, usually framed by discussions about LED panels, processors, and tracking systems. What gets less attention is what actually happens once the lights are on and clients walk in. Virtual production is not only for blockbuster series or studios with Hollywood-scale budgets, and not everyone is working on the next The Mandalorian. For everyday work, the realities are different and often more interesting.

To look past the tech diagrams and into daily practice, we spoke with the team at DoorG Studios in East Providence, Rhode Island. Executive Producer Jenna Rezendes, VP technologist Joe Ross, and Unreal Engine Artist Sam Culbreth walk us through how virtual production functions on real commercial shoots, with real constraints, real schedules, and real clients.

DoorG Studios is a creative production studio based in Rhode Island, specialising in commercial content, branded work, and campaigns that blend traditional production with virtual production. They operate an LED volume designed for practical, day to day shoots rather than cinematic excess. You can find them at door-g.com, explore their studio at door-g.com/studio, or keep up with them on LinkedIn.

Jenna Rezendes sits at the intersection of clients, creatives, and technology. She translates virtual production from something that sounds expensive and mysterious into something clients can actually plan around. Her focus is on communication, preparation, and making sure decisions happen early enough that nobody is surprised on shoot day. You can find Jenna on LinkedIn.

DP: Hi Jenna, what is DoorG?

Jenna Rezendes: Door G is a production studio based in Rhode Island. We have a versatile team of producers, creatives, and artists who love storytelling and keep pushing what’s possible in production. We work on branded content, commercials, and large-scale campaigns. We’re constantly exploring new ways to make production smarter and more efficient, whether that’s through virtual production or traditional filmmaking techniques.

Joe will share more about our physical stage and how it expands what’s possible for our clients, and Sam will get into how our production pipeline supports that. But from a big-picture perspective, Door G is a creative studio that stays ahead of what’s next in technology without losing sight of the human side of storytelling.

DP: What kind of customers use your stage? And what are the usual questions they have when they first come to you?

Jenna Rezendes: We work with a wide range of clients, from agencies and brands to production companies that just need the right space and support. Some clients come to us early on, looking for full creative ideation through production and post. Others already have their concept developed and just need production services, or even a studio rental. We’re set up to scale our support to meet their needs.

When people first reach out, the questions are usually about what’s possible on the stage: how virtual production actually works, what kinds of environments we can create, and how it impacts things like schedule or budget. We have a library of production-ready virtual environments that can be used as is, customised to fit the project, or fully custom-built when needed. It’s exciting to see clients realise that the stage isn’t just a technical tool; it’s a creative space that can open new ways to tell stories.

DP: How has your client communication changed since you started offering virtual production?

Jenna Rezendes: Communication has definitely evolved since we started offering virtual production. A big part of what we do now is education, helping clients understand how this technology changes the flow of a project. The conversations start earlier, and they’re more collaborative from the beginning.

With traditional production, clients are used to making creative decisions once they’re on set or in post. With virtual production, much of that decision-making moves to the front end. We spend more time in previsualization, running test sessions, and showing how scenes will look and feel before anyone arrives on set. That shift has actually deepened client relationships. They’re more involved in shaping the vision early, and they get to see ideas come to life in real time. Once they experience that, they realize how much more efficient and creatively freeing the process can be.

DP: When props are built for a shoot, say a few shelves or counters, can’t they be stored and reused for future productions?

Jenna Rezendes: Absolutely. One of the biggest sustainability advantages of virtual production is that so much of what we create lives in the digital space. Instead of building large practical sets that are used once and torn down, we’re designing digital environments that can be updated, customised, and reused across multiple productions. That dramatically reduces material waste and the carbon footprint that comes with traditional set construction.

For the physical elements, we do need to blend the virtual environments with the practical; we keep things minimal and modular. We’ll often store practical props or set pieces between shoots so they can be repurposed in future environments. It’s a smarter and more sustainable way to work, both creatively and operationally. We’re proud to be certified with the EMA Green Seal for sustainable studio practices, and that really guides how we think about production.

DP: What’s the most common misconception clients have about shooting in a VP stage?

Jenna Rezendes: One of the biggest misconceptions is that virtual production is only for creating worlds that don’t exist “on earth”, like post-apocalyptic landscapes, outer space, or big cinematic settings like The Mandalorian. And yes, it’s incredible for that kind of work, but it’s just as effective for everyday environments that are tricky or difficult to film in. We’ve used virtual production for medical facilities and retail spaces where on-location shooting can be disruptive, expensive, or constrained by logistics. With virtual production, we can easily recreate those environments with total control over lighting, timing, and camera movement.

Another misconception is the “fix it in post” mindset. In virtual production, so much of the decision-making happens on the front end. You’re designing and visualising the environment before you shoot, so there’s less guesswork later. Once clients experience that process and see the world on the LED stage in real time, it changes how they think about production entirely. It’s not about doing everything in post anymore; it’s about getting it right in the moment.

DP: When you prepare a shoot, what do you wish every customer already understood?

Jenna Rezendes: I wish every client understood how much smoother and more creative the process becomes when we’re all aligned early in pre-production. There’s really no such thing as a perfectly prepared project, but the ones that set us up for success are those where clients share the right materials and collaborate with us early in the process. When communication is open from day one, and everyone is aligned on intent, technical needs, and delivery formats, it creates a strong foundation that saves a lot of time later. Clear references, organised assets, and early creative collaboration give our team what we need to prepare for production as effectively as possible.

Especially with VP, a little extra time up front for pre-production and previsualization makes a huge difference once we’re on set. Our post-production process is already streamlined, so the last thing you want to do is condense your pre-pro and pre-vis phases. That’s where we work through creative and technical challenges before they ever reach the stage, which ultimately leads to a smoother, more efficient shoot.

DP: And just to end on a fun note: you’ve spent quite a few minutes inside that stage. What’s the most amazing thing you’ve seen so far?

Jenna Rezendes: Nothing will ever top the first time I saw virtual production in action. That moment when it clicked for me that this technology wasn’t just for Hollywood but could completely change how we tell stories across all kinds of productions. Seeing a camera move through a digital environment in real time, with everything reacting naturally, was honestly jaw-dropping.

Since then, every project has its own amazing moment. Sometimes it’s watching a client experience it for the first time and seeing that same lightbulb go off. Other times it’s the thrill of seeing our team pull off something that felt impossible a few weeks earlier. The technology is incredible, but it’s those human reactions, the excitement, the surprise, and the creativity, that make it truly special.

DP: How do you manage creative decision-making between physical and digital departments?

Jenna Rezendes: Our production design team, Unreal artists, and DPs are in conversation from the earliest stages of a project so that creative ideas and technical realities stay aligned as things evolve. The goal is to ensure that what looks beautiful on screen also makes sense within the constraints of lighting, camera movement, and real-world space.

We approach it as one unified team rather than separate departments. The virtual art department might start developing the environment while our physical team experiments with lighting or set integration, and those discoveries flow back and forth until everything feels cohesive. That collaboration lets us balance creative freedom with practical execution, so nothing gets lost in translation between the real and virtual worlds.

Joe Ross, our technical director, and Sam Culbreth, our lead Unreal Engine designer, can speak more to how we balance creative with technology. They do a fantastic job creating the bridge between the two.

The Stage & Its Hardware

Joe Ross (LinkedIn) did not wake up one morning and decide to build an LED volume. His background runs through nearly a decade of hands on video and technology roles at addventures, where he progressed from managing video systems to senior leadership in video technology. Joe holds a Bachelor of Science in Communication and Media Studies from Fitchburg State University.

DP: So Joe, I hear you have a very big TV at work.

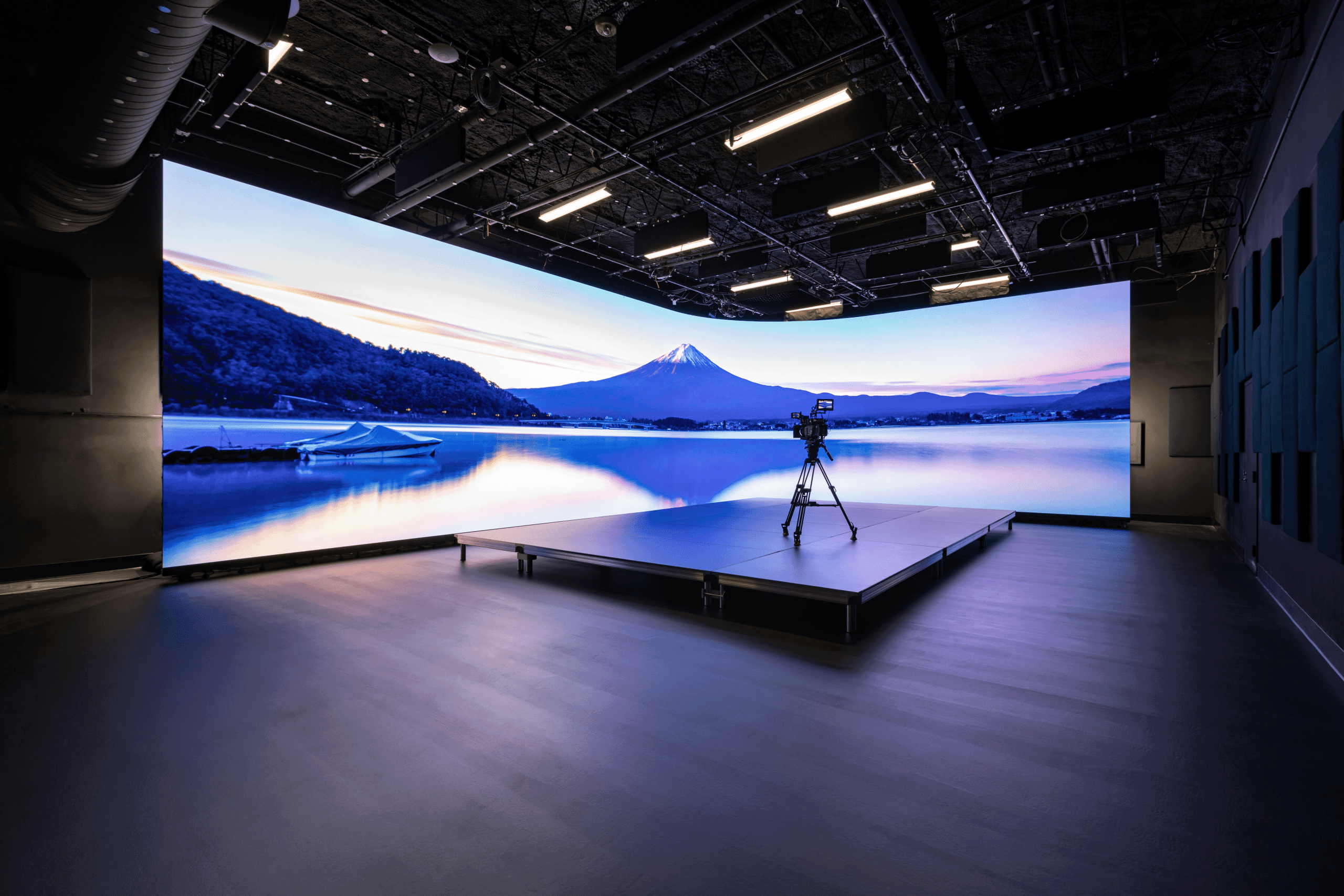

Joe Ross: Haha, I actually also refer to the volume as a big TV too! And the Brompton processors are just oversized HDMI adapters. The volume is 17m wide and 4m tall, so unfortunately, you’d probably get whiplash trying to watch TV across the whole thing. Those HDMI adapters I referred to are the Brompton SX40s.

We have three of them pushing pixels to our wall. 17,825,792 pixels to be exact, the full resolution is 8704×2048. We’re using a combination of InfiLED’s DBmk2 and X panels. The Xs are for the curve in the middle, since we have a curved L-shaped wall, which uses curved panels for the bend.

We went with that shape since it allowed us to make the best use of our studio size. It pretty much extends the full length of two sides of our studio. That allows us to shoot longer shots on one side of the volume and wider shots or trucking shots on the longer side of the wall.

Most often, we actually shoot into the curved corner of the wall, since it gives us the most flexibility to move the camera around without catching the edges of the wall, and it makes use of reflections and ambient light from both straight sides of the volume.

In terms of camera: We work with any sort. The refresh rate on our panels is fast enough that most modern cameras have no problem with any tearing or banding while shooting into the volume. We even have some people shoot with their phones with just default settings and have no problem. That said, we have an FX9 as our in-house camera, and mostly rent the Venice 2, RED V-Raptor [X], or Arri Mini LF. The RED Raptor in particular pairs nicely with the volume, since it has a global shutter, which helps even further with any refresh rate problems.

It also ties in with our Brompton processors and allows us to record two separate feeds from one camera: one with the 3D Unreal Scene on the volume and one with just green screen on the volume. The processors just alternate between the 3D scene and green, then the RED captures a separate feed for both, alternating each frame. It’s pretty wild!

DP: How long does it take to set up and calibrate the stage for a new project?

Joe Ross: That’s definitely an “it depends” kind of question (laughs). If we’re doing a basic shoot with all of our standard in-house gear and well-tested Unreal levels, then everything is pretty much ready to boot up and go. So that may only take half an hour to an hour. We just need to reboot all the PCs to start fresh, connect them all to our Facilis server where the projects are stored, then launch a multi-user server for all of our Unreal machines to sync to.

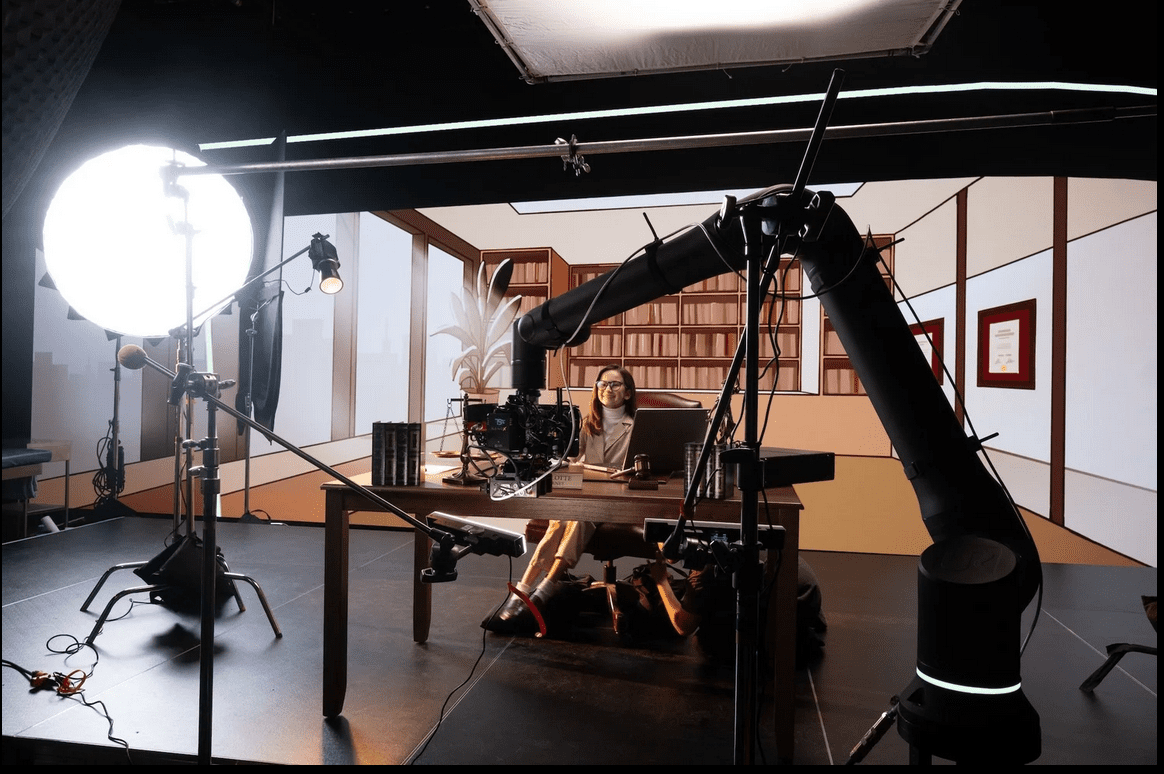

If it’s a brand new shoot with rental gear and Unreal Projects that we haven’t shot in studio with before, then it can take much more time, up to a full day, to ensure all the pieces are playing nice with each other. The things that would require extra time are things like, calibrating the mo-sys camera tracking offset from the camera sensor to make sure the tracking is accurate, setting up and testing communication between our Unreal editors and render node and any on set tech that needs it, like a robot camera arm or DMX lights, then going through our shotlist and camera moves to make sure the Unreal level is playing nice with the full setup.

The robot arm is a big one, since our studio and Unreal Engine nDisplay config is set up by default to our Mo-Sys star tracker’s map. When we bring in the robot arm, we need to configure our nDisplay config to match the positioning and tracking system coming straight from the robot arm. We could just keep the Mo-Sys on the camera while it’s on the arm, but then we lose some of the benefits of having a robot arm tied into Unreal, plus our model of the Mo-Sys is older and pretty bulky, so it adds some decent heft to the rig.

DP: How do you collaborate with cinematographers who might be new to LED volumes?

Joe Ross: We, of course, do our best to “fix it in Pre” and have the DP and Director heavily involved while building out the virtual scenes, so they have a good idea of what things will look like when they step on set. From there, honestly, we keep things pretty close to traditional production from their standpoint. They just need to work with our virtual gaffer and the practical gaffer when lighting changes are needed in the scene.

That said, we have a few key pointers for first-time VP shooters. One is to try to keep the brightness up on the volume and stop down or ND down in the camera to get the best performance out of the volume in terms of colour and dynamic range. Another is to keep an eye out for any moire; if the focus plane is too close to the wall, you’ll start to see it.

DP: A stage is more than a screen, a camera, and a server. Can you tell us about the rest of your setup?

Joe Ross: Yeah absolutely. For tracking systems, we use the Mo-Sys StarTracker, so our studio ceiling is covered with tracking dots. Probably more than we need, but that gives us very stable tracking, even when flags and lights get in the way of the Mo-Sys IR camera.

We have a wild wall as well, which we made a custom rolling rig for, so we can move it around the studio as needed for reflections and ambient light that matches our scene. That’s really all we have in-house, but often we will rent robotic camera arms that communicate with Unreal Engine. Those are a perfect pairing with the volume because they allow us to not only have very interesting, repeatable moves, but also to tell Unreal Engine where the camera will be before it gets there, cutting down on any delay between camera tracking and the perspective shift on the volume.

DP: You recently shot for a medical imaging company, and I heard there was sand involved. Please tell me you didn’t bring a bucket of it near your panels.

Joe Ross: Haha, yeah, that was my initial reaction when someone wanted to bring sand into the studio as well. There have been a couple of shoots with sand involved, actually. The one with medical equipment was a spot that cut from a hospital scene to a soldier stationed out in a desert. For that one, there wasn’t any physical sand used, but our virtual and physical art teams did a great job making it look very convincing!

The other instance of sand was actually for a music video shot in a sort of dystopian desert, city ruin type scene. For that one, we actually did bring real sand into the studio! I was definitely a little concerned about the grains of sand in the air but we kept it contained on a raised stage and kept it removed from the wall at least a few meters. We made sure no fans were used on set while the sand was there as well, and we had air scrubbers running in front of the volume to pull any particles down and away from the LEDs.

In terms of keeping the volume clean, it’s tough to regularly clean the whole volume, but when needed, we’ll use compressed air or a vacuum with a gentle attachment to remove any dust or debris that may build up in the shader layer of the LED panels.

DP: When one of those LED panels goes dark, what happens next?

Joe Ross: Ah, the dreaded black panel… Well, it depends on where the issue stems from. So the first thing to do is diagnose whether it’s an issue with the panel/LED diodes, the internal PCB, or even software. If it’s just the LED panel itself, we will just pop it right out and replace it with spare panels that we got with our original order. It’s important to get extra panels with a volume like this because each batch of LED panels will be slightly different when they come out of the manufacturing process. So, having panels from the same batch ensures they match perfectly.

DP: What are the biggest maintenance challenges with LED volumes?

Joe Ross: The heat for sure! It can feel like a sauna in there at times if not managed properly. We definitely underestimated how much of a problem the heat from these panels would be. We’ve run our AC so hard trying to keep up with it that it keeps freezing over, and our facilities manager has had to literally chip the ice off it on the roof to get it back up and running again.

We also have installed a secondary mini-split because the main AC wasn’t enough! Even now, we’re brainstorming better ways to remove heat from the studio instead of trying to pipe cold air in. We may be installing an exhaust in the ceiling to do just that!

DP: What’s the most creative or unusual technical solution you’ve had to invent on set?

Joe Ross: Ahh, this is the fun part! Don’t tell anyone, but I secretly love it when things break, and I need to scramble to fix them (Laughs). The old reliable workaround for many of our Unreal Engine hitches is to just freeze the image on the wall using our Brompton processors directly, while we work on rebooting or fixing issues or crashing in Unreal, without anyone noticing.

I think most of the more fun/interesting fixes happen in Unreal Engine. When things just aren’t working the way they are supposed to, you just do whatever works. One particularly odd instance was when we had a scene that traversed two rooms in two locations, stitched together in Unreal. The talent in the scene walked from a retail environment straight into their living room. For some reason, the lighting would not stay consistent, and lights from the living room would just pop on once the camera reached a certain point.

So after much head-scratching, we figured out that if we just stretch the frustum (basically the virtual camera’s vision) far out to the right side, so that it just thought that it was always in both locations at all times, then it would render all the lighting consistently throughout the move. Not the most elegant solution, but I always say, “if it’s stupid and it works, it’s not stupid.”

The Brain Bar & Pipeline

Samuel Culbreth (LinkedIn) comes from the side of production where things are built, broken, rebuilt, and then optimised again because the frame rate said so. His background is in 3D environment creation, asset building, and realtime work using Unreal, Maya, and Substance, with an education in Game and Interactive Media Design from New England Institute of Technology. Before stepping into his current role as Virtual Art Department Lead, Sam worked as an Unreal Engine artist at addventures.

DP: Sam, with a job title like “Brain Bar Operator,” do you have the coolest business card in the world?

Sam Culbreth: So there are a few terms for it, and not all of them are as fun, but that’s actually only a portion of what I do. Most of my time is spent in pre-production building the environments and preparing them for a shoot.

Then, when we’re on set, it becomes the “central nervous system” of a virtual production stage. From The Brain Bar, we are loading our environments onto the LED wall, monitoring, and making adjustments to the scene. The scene’s virtual camera is connected with our tracking system, so it constantly updates its coordinates based on where we move the real camera.

DP: When you power up your Brain Bar, what’s actually howling in there?

Sam Culbreth: This is more of a question for Joe Ross, as he built our brain bar setup. But the specs are quite powerful to keep up with what we’re doing on the render node. If I had to make an upgrade.. Well.. I can always use more monitors!

Joe Ross: They are definitely pretty hardy. Most of our PCs were built in collaboration with Puget Systems out in Seattle. They’re always great to work with and are so diligent in testing which parts are best suited to your use case. At the Brain Bar, our machines run AMD Ryzen 9 CPUs and Nvidia 4090 GPUs. Our render node has an AMD Threadripper Pro CPU, which I’ve always wanted an excuse to use (Laughs), and two Nvidia 6000 ADA series GPUs. In terms of upgrades, we’re still running vanilla Unreal Engine and no real media server, so right now we’re looking into a Pixera, Disguise or Assimilate Live FX solution to help streamline and optimise some things.

DP: How do you handle colour management between Unreal, the LED wall, and camera output?

Sam Culbreth: This can be tricky, as we’re diving through multiple layers of colour between the wall, Unreal Engine, and the camera. Unreal Engine has built-in colour management tools for features like ACES. And we try to keep our wall settings consistent for each shoot.

But in the end, what really matters is what we’re seeing through that final camera output. Having that output visible in real time gives us plenty of opportunities to make adjustments before we film.

DP: When Jenna brings you a new project, what do you look for in the Unreal scene setup that a customer delivers?

Sam Culbreth: It all depends! I’m always happy to get references up front so I can start strategising right away. If there are preexisting 3D files, I can often convert them over to use in our scenes. As a general rule for textures, you want powers of twos. For any close or large textures, I like to stick to 4k. You can still get away with lower most of the time, especially if it’s far in the background. I’ll even go down to 256 if it’s a smaller, less detailed object.

DP: How do you document or archive the technical setup for each project?

Sam Culbreth: We have a standard template that we adapt with each new version of Unreal Engine. That way, I’m able to migrate any levels that have been built and keep all of our project settings consistent. I also tend to make a copy of the project before a shoot, in case anything changes dramatically while we’re on set. Once it’s over, we have a process for archiving old projects securely on-site in case we ever need to pull them back up.

DP: If you could write a wish list for your customers, what would it include?

Sam Culbreth: Come in with a solid plan and vision long before we’re on set. We have some wiggle room to make changes, but your visuals should really be locked in before we’re shooting. If you’re uncertain about something, we can prepare a few options, but knowing that ahead of time gives us a chance to make preparations to adapt that won’t require on-set scrambling or potential crashes. Fewer changes on set means better stability and more precious time getting content.

DP: How do you coordinate real-time updates between Unreal, camera tracking, and lighting?

Sam Culbreth: That’s the neat part, you don’t! Once our motion tracking system is connected and the project is launched, the camera tracking handles itself. Most updates I make to the scene are typically immediately visible on the wall. Though occasionally I’ll have to save the scene to push the changes. As for latency, we test our scenes ahead of time to make sure they’re meeting our goals. We have a process for dividing up and disabling parts of our map when we need to improve our performance.

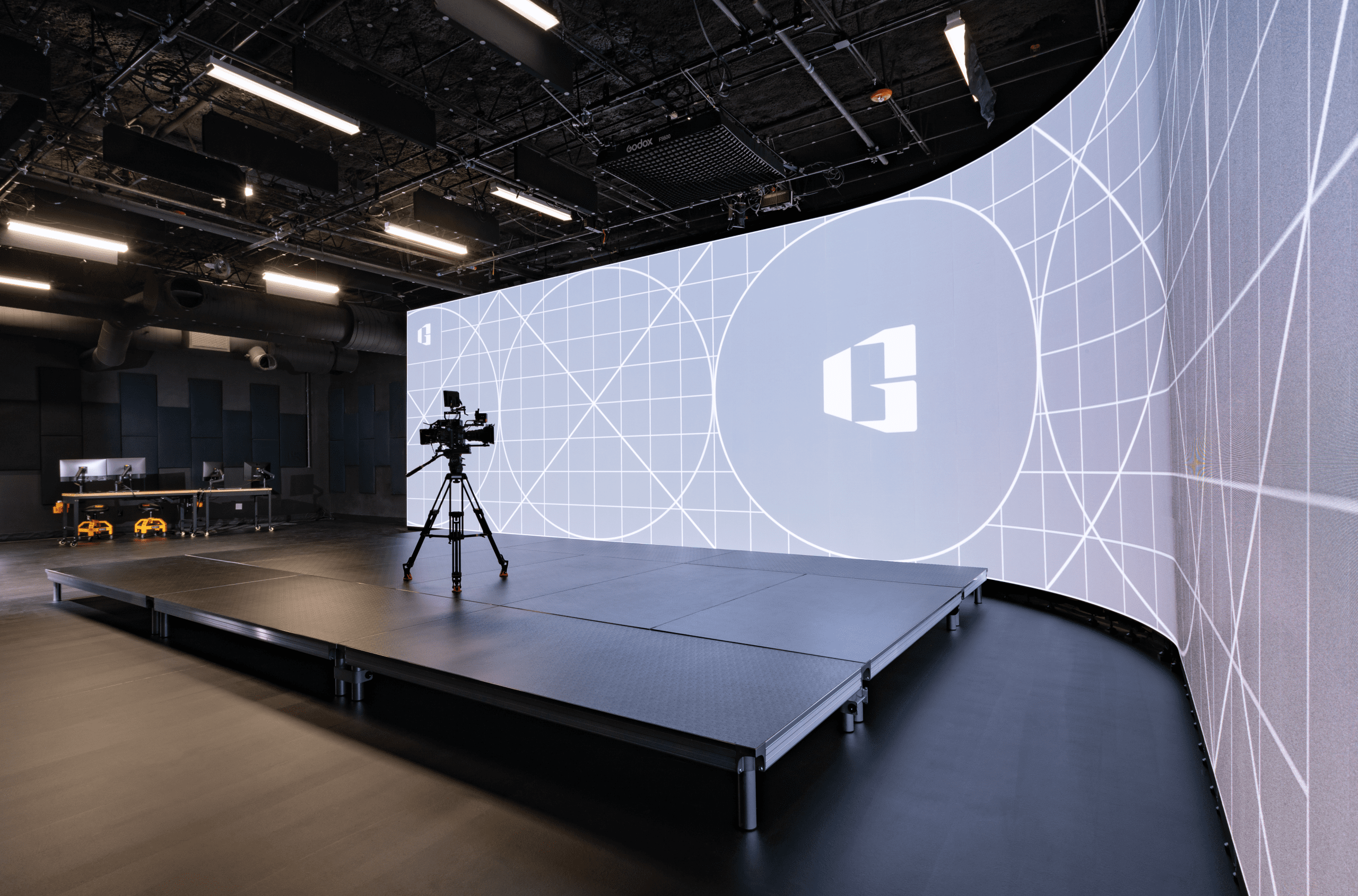

DP: What’s your favourite Alignment / test pattern?

Sam Culbreth: True Neutral, or Chaotic Good. – Oh test pattern, I don’t have one. But I tend to gravitate toward a synthwave aesthetic for screensavers.

DP: Gaussian splats are picking up momentum. Can you simply load one into your scene?

Sam Culbreth: We’ve experimented with a few different scan methods, and there is a bit of a process required to make it possible without totally overloading the system. Gaussian splatting is a very powerful technique that I’m hoping we can make more use of in the future, but it hasn’t been necessary for our builds.

DP: What tools or plugins have become indispensable in your workflow?

Sam Culbreth: Of course, we have the necessary Virtual Production Tools like nDisplay, LiveLink, and Mo-sys. But I’ve really enjoyed using PolygonFlow’s Dash plugin and NVIDIA’s DLSS plugin. These tools really speed up my workflow when it comes to building environments, performance, and rendering.

DP: And finally, the question every reader is thinking: can you game on the DoorG stage after hours?

Sam Culbreth: I certainly hope to! We’ve tested a few things on it before, and it can absolutely serve as a massive monitor for maximum immersion. Furthermore, we’ve got plans to utilise our motion-tracking systems and VR environments to create some interesting options for virtual scouting and other experiences.