Table of Contents Show

Since Blackmagic made Davinci Resolve available free of charge as a professional colour correction tool, the demand from media makers to optimise image content even further, both technically and creatively, has increased significantly. It is fair to say that colour correction has reached the masses. VFX and editing programs are also developing ever better colour correction functions. After Effects has finally integrated waveform and vectorscope functions. This means that one of the most important image control functions – especially for colour correction – has finally been integrated into a very widely used image design tool for VFX.

It would therefore be only logical to optimise the functionality of the monitor as well. Unfortunately, the issue of colour accuracy in monitors is a drama, although monitor manufacturers have certainly improved in this respect. I would first like to refer you to my monitor article on the subject of reference monitors: “Monitoring for colour grading”

(DP 04:2013, free to download at digitalproduction.com). But to shorten the diversions there a little, here are some explanations on the subject of displays and monitoring. There are roughly 3 classes of display quality.

- Class 1 are the reference monitors (also known as Class A), which have colour reference capability and professional interfaces such as SDI.

- Class 2 are professional video monitors with corresponding video interfaces such as SDI, but they do not necessarily have colour-accurate picture quality.

- Class 3 are simple devices of all kinds according to the motto “Ok, I can see a picture”, i.e. also consumer TV sets.

Class 1 devices and the delivery quality

Even if you spend 30,000 euros on a reference monitor, this does not mean that the device will be delivered sufficiently calibrated. I’m not going to name a manufacturer, but one of the largest and best-known does not do this. In practice, the deviations are so great that the Class 1 title (without the final calibration) should actually be revoked.

There is a class 2 device from the same manufacturer that can also achieve class 1 suitability with the same calibration effort that is always necessary for the class 1 device. This means that it can be financially worthwhile to look into the subject of calibration and learn what works and, above all, how you can save a lot of money. And that brings us to the following appliance classes. Because in some cases it is possible to make class 2 or 3 devices suitable for colour reference.

What does a manufacturer do to trim panels for colour accuracy?

First of all, manufacturers like to install the same technology in different devices in order to save development costs, manufacturing costs, etc. Then they limit functionalities by simply switching off functions via software or, in the case of monitors, simply “miscalibrating” the settings. The latter can be determined and corrected using calibration measurements. In this way, a class 2 device can perhaps achieve class 1 quality after all.

Back to the question: What makes the class 1 device colour-accurate? Nowadays, this is done by software processing using 3D LUT. In contrast to a 1D/2D LUT, a 3D LUT can shift individual colour locations without significantly affecting others (logically depending on the resolution). With a 2D LUT, you can only change the white point and/or the gamma. Both points are also important for the reference suitability, but the chromaticity coordinates of each colour are the most important indicator for the binding of e.g. skin tones or any other colour.

In order to generate a 3D LUT, several thousand colour locations must be measured and, if necessary, the 3D LUT must be designed using calculations so that the individual colour location errors are corrected. Every good reference monitor works internally with such 3D LUTs – the same ones that can be used to purchase and transform film looks, for example.

According to the manufacturer’s specifications, many class 2 devices meet the limits of the colour spaces such as “99% Adobe RGB” or “100%” sRGB/EBU/Rec. 709 (the three are all identical in terms of colour!). One might think that the specification 100% would be a statement on colour accuracy or reference suitability, but far from it.

These are only the corner points of R G B, and 100% does not mean that the corner points are where they should be – they can be 110%, 105% and 99% for R G B, but 100% coverage has been achieved mathematically. And it gets even worse: 100% coverage of the corner points of the colour space does not even begin to mean that the secondary colours such as C, Y and M are in the correct place. And ultimately even more important: almost all colours that exist within the colour space are not in their correct locations.

Measuring devices for monitor calibration

The beginner’s dilemma: When I started to deal with the subject of monitor calibration myself, I had a classic career. As a layman without any useful test articles, I started buying the usual entry-level products that are still available on the market today: Spyder, i1Display Pro and whatever else was available, spending huge sums of money. The i1Pro, for example, which is the cheapest spectrophotometer, costs at least 1,000 euros, depending on the bundle.

At the latest after I owned 5 measuring devices, I started to spin and question the quality of my service. I became almost dizzy from the extent of the measurement deviations, even with devices from the same manufacturer. It then took me years of research and learning (who buys cheap, buys twice? No, easily five times!) to find out what the reasons for the deviations were in detail.

The professional league: Spectrophotometers are the only measuring devices that are capable of measuring any light source as precisely as possible, regardless of its characteristics, without the need for counter-calibration. Good measuring devices are not temperature-dependent and, above all, measure without contact. All entry-level devices hang or stick to the panel and the sometimes strong heat transfer from the light sources has a considerable influence on the measuring accuracy – the longer the display is in operation, i.e. the warmer the panel and therefore the measuring device, the greater the measuring errors.

For a display to be able to show colours correctly at all, it must first be brought up to operating temperature. For many manufacturers, this is only the case after about 30 minutes, so you can only start measuring after half an hour. Then, however, the measuring device also warms up quickly and constantly changes the measurement results due to its own temperature changes.

A Klein K1O is the fastest way to produce 3D LUTs and has one of the best dynamic ranges, particularly important in the shadow area, but also for HDR or room light measurements

Light characteristics of light sources

The inexpensive entry-level measuring devices under 1,000 euros are all colourimeters: basically camera sensors that react with varying degrees of sensitivity to different spectral characteristics. They do not measure light spectra directly, but determine the colours indirectly. Although there are rough profiles for different types of light sources such as LCD or plasma, there are sometimes considerable deviations even within these type classes. These can be so great that you can mis-calibrate a perhaps good consumer TV set with such an entry-level measuring device, so that you would have been much better off without calibration. The temperature problem has not yet been taken into account.

Is 6,000 euros enough for a measuring device with the necessary measuring accuracy?

Unless it is a spectrophotometer, unfortunately not, and there are no usable ones at that price. So why do these devices exist at all?

Spectrophotometers have several disadvantages: Firstly, they are usually extremely slow, several seconds can pass per measurement. Secondly, they are not very sensitive to light: the darker the monitor image, the longer the measurement takes or measurement errors occur, especially around the usual black level of monitors (below 20 cd/m2). And thirdly, some people are no longer able to measure the black levels of OLEDs or very good LCD devices such as the Dolby reference monitor. However, technological progress has provided a partial remedy: the German manufacturer Jeti has developed a new device that has greatly optimised or even completely eliminated all three shortcomings, except for the speed, which is still in need of improvement. I was able to test the Spectraval 1501 extensively during the HandsOnXK workshop and had plenty of different monitors on site. At the same time, I had the Jeti Specbot 1211 from the HFF Munich at my disposal, where the workshop took place. It was pleasing to see that two measuring devices deliver almost exactly the same measurement results. However, the Jeti 1211 is only suitable for standard calibrations such as gain and bias, i.e. 2D LUT calibrations. I always call this manual calibration.

This assumes that you already have reference monitors, where basically only the white point and gamma need to be corrected – for example, to correct the drift caused by wear and tear or the defective delivery condition. The 1211 is not suitable for a 3D LUT calibration measurement, but the 1501 is. It could even measure the Dolby monitor completely if it wasn’t still so much slower than a colourimeter. It has become faster, but the difference would be in the range of almost a day to a few hours for extensive measurements.

High-quality colourimeters up to approx. 8,000 euros

The Klein K10a, which I personally use – and which unfortunately has a price tag of this size – has the best price-performance ratio for fast and, above all, temperature-insensitive colourimeters. I use a spectrophotometer to counter-calibrate it for each monitor type with manufacturer-specific accuracy.

This is the only way to get reliable, verifiable, repeatable results. As new devices are constantly being released, every new monitor has to be re-measured. So you need two measuring devices – one that works fast enough to take several thousand measurements for a 3D LUT in a reasonable time per device, and one to determine the necessary counter-calibrations. Unfortunately, good spectrophotometers start at around 9,000 euros. The Minolta CS 2000 costs around 40,000 euros and is regarded as the best reference spectrophotometer. It is used by Spectracal to carry out the counter-calibrations for the i1Display Pro, among others, and thus make it a CS6 product.

But as I said, the small number of profiles limits this device extremely. However, if you buy a TV-Logic or a Dreamcolor, this is exactly the right product for useful calibrations, but only for manual corrections due to the temperature problem.

About the measuring method

In order to be able to measure colours, they must first be generated – this requires automated image generators. Spectracal offers a wealth of supported external devices as well as some internal software-based generators.

This almost inevitably brings with it a number of potential sources of error, particularly with regard to the colour range: 16-235, usually known as the broadcast range, and 0-255 full range (computer monitors). However, there is also the camera range that high-quality broadcast cameras still deliver: 16-255. A reference monitor should also deliver this range. It’s hard to believe, but quite a few development engineers at various manufacturers such as Aja, Blackmagic, Avid, Dolby or Eizo have sometimes only permitted the 16-235 range when developing digital monitors or video IOs.

Every CRT monitor was previously able to display 16-255 correctly without clipping. All these manufacturers have now removed this limitation – Dolby has even invented its own name for it: SMPTE . Every monitor should be calibrated to SMPTE range, but not every possible test generator workflow at Spectracal makes this range possible.

You could, for example, have the idea of taking a laptop and using its HDMI output and the test pattern generator integrated in the Calman to connect the HDMI output directly to the video monitor, as a second monitor in the operating system, so to speak. Wrong idea – unfortunately 99.9% of HDMI outputs on computer graphics cards limit the range to Broadcast Legal Range, regardless of the range set in the Calman software. There are other reasons not to rely on test pattern generators based on the graphics card and its outputs, unless I just want to calibrate the computer monitor itself. External image generators, which could also be remotely controlled by the Calman software via the computer, are again quite expensive and can cost another 1,000 euros or much more. If you already have a video I/O such as from Blackmagic or Aja (the cheapest models can be found here), you could use the paid-for Virtual Forge software from Spectracal.

As you can probably already see, the complexity of the whole matter is not without its challenges, and training and purchasing advice can help you avoid the most common application pitfalls.

Spectracal Software & Meter Bundles

So if you intend to calibrate monitors yourself, you can save a lot of money if you invest in the right measuring device right away, otherwise you can save yourself almost no money at all.

Spectracal has been offering inexpensive colourimeters in a bundle with its measurement software for several years now, but from a certain price level upwards, these are already equipped with more profiles that have been counter-calibrated with high-quality, sometimes very expensive spectrophotometers in order to compensate for the measurement errors using software processing: basically the same thing we want to do with 3D LUTs and the monitors in the end.

The Calman Spectracal C6 is an optimised i1Display Pro, which is recognised by serial number in the Calman software, which then downloads the measured counter-calibration colour matrices online. This means that monitors from Eizo or an HP Dreamcolor, for example, can be colour calibrated, which would lead to errors with an i1Display Pro purchased from XRite.

Spectracal is the only company to offer ready-made profiles that are precisely matched to these monitors and their light source characteristics. However, the selection is limited to very few well-known manufacturers. As soon as you want to calibrate less well-known devices, it’s already over again and you need spectrophotometers to determine correction matrices first.

Variants of the Calman software

The entry-level versions such as Calman Control with or without colourimeter are, as described above, more suitable for rough orientation as to which projector or monitor preset is suitable as the correct preset in order to meet the requirements such as the correct colour temperature to some extent. Unfortunately, there is no guarantee that you will not make more mistakes. However, as most monitor/TV devices come from Asia or were developed there, the default settings of these devices are usually far too blue and so much so that the measurement errors of cheap colourimeters are negligible – but as soon as the colour temperature has been roughly corrected, it remains rough. More in-depth functionalities such as those in the Enthusiast version, which also enables 3D LUT creation, are pointless without high-end measuring devices.

Calman RGB is only suitable for calibrating computer or laptop monitors, whereby here too only the white balance is corrected across the grey scales, i.e. including gamma. If you buy Spyder or i1Display Pro directly, you actually get the same functionality with the in-house software tools. However, Spectracal claims to deliver more accurate results here and this certainly applies to the Spectracal CS6 meter and monitors for which a suitable measurement profile exists.

Calman RGB is a must for anyone who does VFX or animation and does not use Eizos as a GUI monitor and who already has onboard measuring devices – whether laptop or external graphics monitor.

Alternatively, all monitors from Eizo that currently have built-in measuring devices are the better concept. Their measuring devices are counter-calibrated to the light source type, the software for calibration is built into the monitor and regular measurements can be programmed automatically in the monitor – see, for example, our test earlier in this issue. Calman RGB is therefore more worthwhile for a company that owns several different monitors from other brands or monitors that are older than Eizos with an onboard measuring device. Of course, you also have to set the correct colour space and colour temperature in the menu for the Eizos; the measuring devices do not tell you whether this is correct.

Calman RGB displays the measured values in a graphically appealing way. This helps with devices that lack monitor presets such as sRGB, EBU, Rec. 709, gamma, colour temperature, colour range, HDMI range etc.

An investment in Calman Studio makes sense if you want to calibrate reference video monitors or projectors. From the Studio Express version onwards, there is an ingenious feature: Lightning LUT. This allows a 4,000-point 3D LUT to be measured across the entire colour space in just five minutes with only approx. 100 measuring points. Sometimes the result is better than 1,000 measuring points for monitors with good initial values (lower deviations), which can take up to 90 minutes, depending on the speed of the measuring device and the pattern generator.

Calman Ultimate: the version with all functions. Among other things, it can also be used to directly control high-quality home cinema and high-end TV sets with their own internal calibration functions. However, this is no guarantee of achieving the best results.

The fewest compromises – apart from one

The most ideal method for affordable optimisation of the colour accuracy of virtually any device is to loop an external 3D LUTbox into the video path and implement the 3D calibration measurements to generate this 3D LUT for it.

Aja has a LUTbox in its programme, but it does not support 4K resolution. Blackmagic has two devices: the HDLink for HD and the Terranex Mini SDI 2 HDMI for up to 4K60p. Flanders Scientific from the USA, who have built one of the best HD reference OLED monitors, can also go up to 4K60p when combined with two Box IOs. All the devices mentioned can be supplied by Calman with suitable 3D LUT versions, and in some cases it is even possible to control the boxes directly and thus generate the LUT directly in the box during the measurements.

One compromise should be mentioned: 3D LUT processing takes time. And not to forget: Depending on how much time the display itself needs for processing, the image delay to the audio is noticeable and should be equalised using an audio delay box if you want or need to be lip-synced to the external monitor.

Conclusion

A practical example: You can get the 3D LUTbox and 3D calibration from a 4K 50-inch HDR UHD TV, which may only cost around €1,000, for the same use, and thus get a device for around €2,000 that you can hang on the wall as a client monitor – and which shows virtually no differences in colour to the €30,000 reference monitor, provided that it has also been calibrated correctly.

Of course, this is apart from the problems I described in detail in my other monitor article, such as the often inadequate viewing angle stability, which can affect even the most expensive reference monitors.

However, the initial investment in appropriate equipment and expertise that can do this adequately is very high and is certainly only worthwhile for companies with well over 10 workstations and with permanent staff, where the expertise does not immediately migrate again, or if it is only about the GUI monitors.

For everyone else, it is certainly more favourable to employ a service provider they trust. With today’s display technologies, recalibration every 12 months is sufficient. The fact that many programmes or monitors themselves offer recalibrations every month is nonsense. Only projectors that run every day can show significant deviations after 3 to 6 months.

Xrite i1 Display Pro Bundle

Xrite i1 Display Pro Bundle

Xrite i1 Display Pro BundleApple devices are often used in the media industry for working with media. It’s not uncommon for discussions like this to arise:

“Yes, but it looks much worse on my Macbook, I want it to look equally good on my iPhone and my Mac!”

This is where many colourists despair of their customers. Not least when almost only media people use Macs and they are practically insignificant worldwide because their penetration rate is in the single-digit percentage range and therefore such a claim is not produced for the final audience. But basically this problem applies to the cross-section of all displays. But they can deviate in exactly the opposite direction, and what looks good on an iPhone can look even worse on a PC monitor or UHD TV. It’s not a good idea to accept this customer/producer request. It’s not an easy job for the colourist to explain this to the customer without letting them know that they actually have no idea what they’re getting. It’s not uncommon for the colourist to save himself by recommending that the customer calibrate his laptop so that he sees the same thing as in grading. Let’s do it and keep it short.

Conclusion

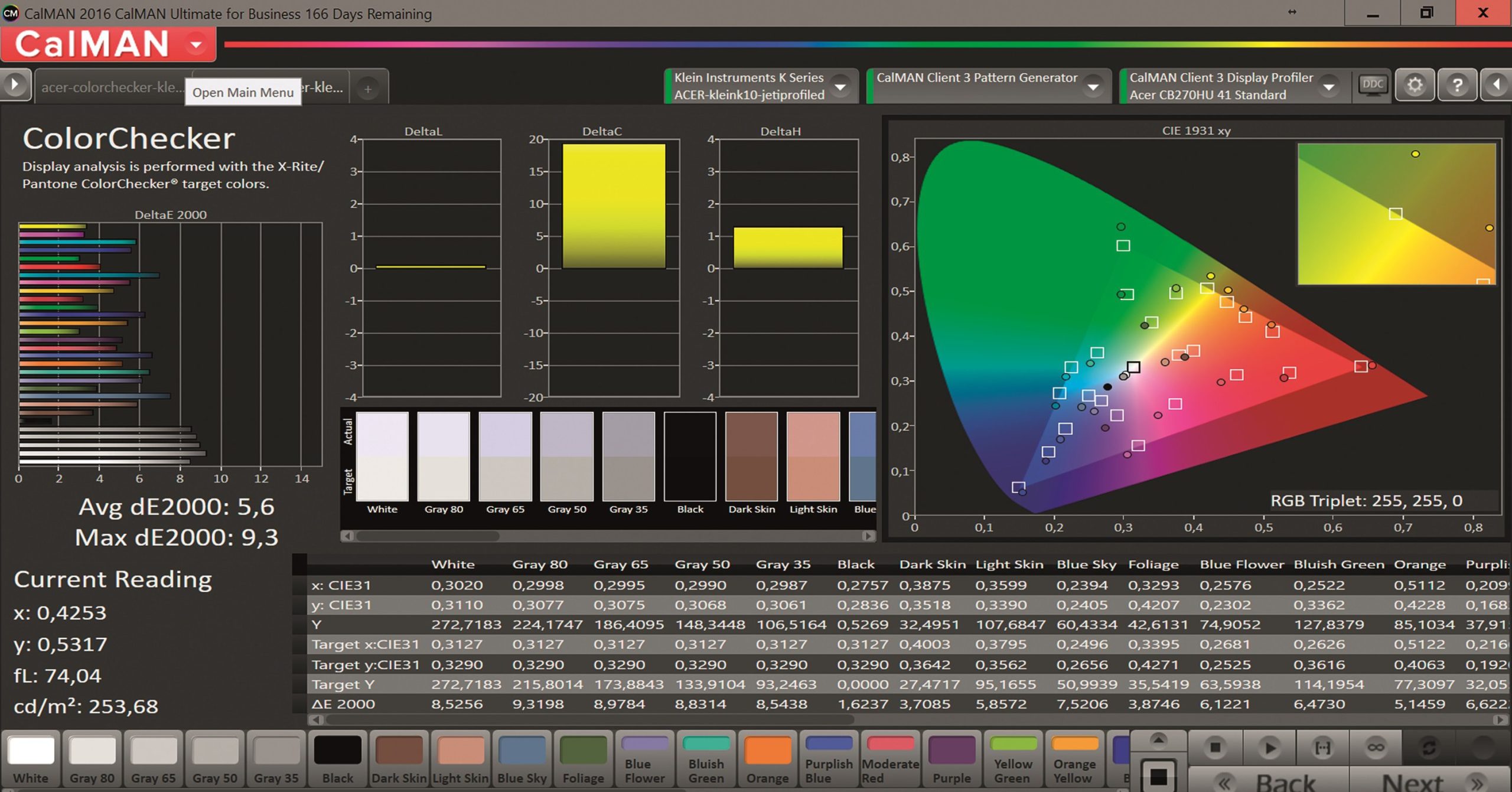

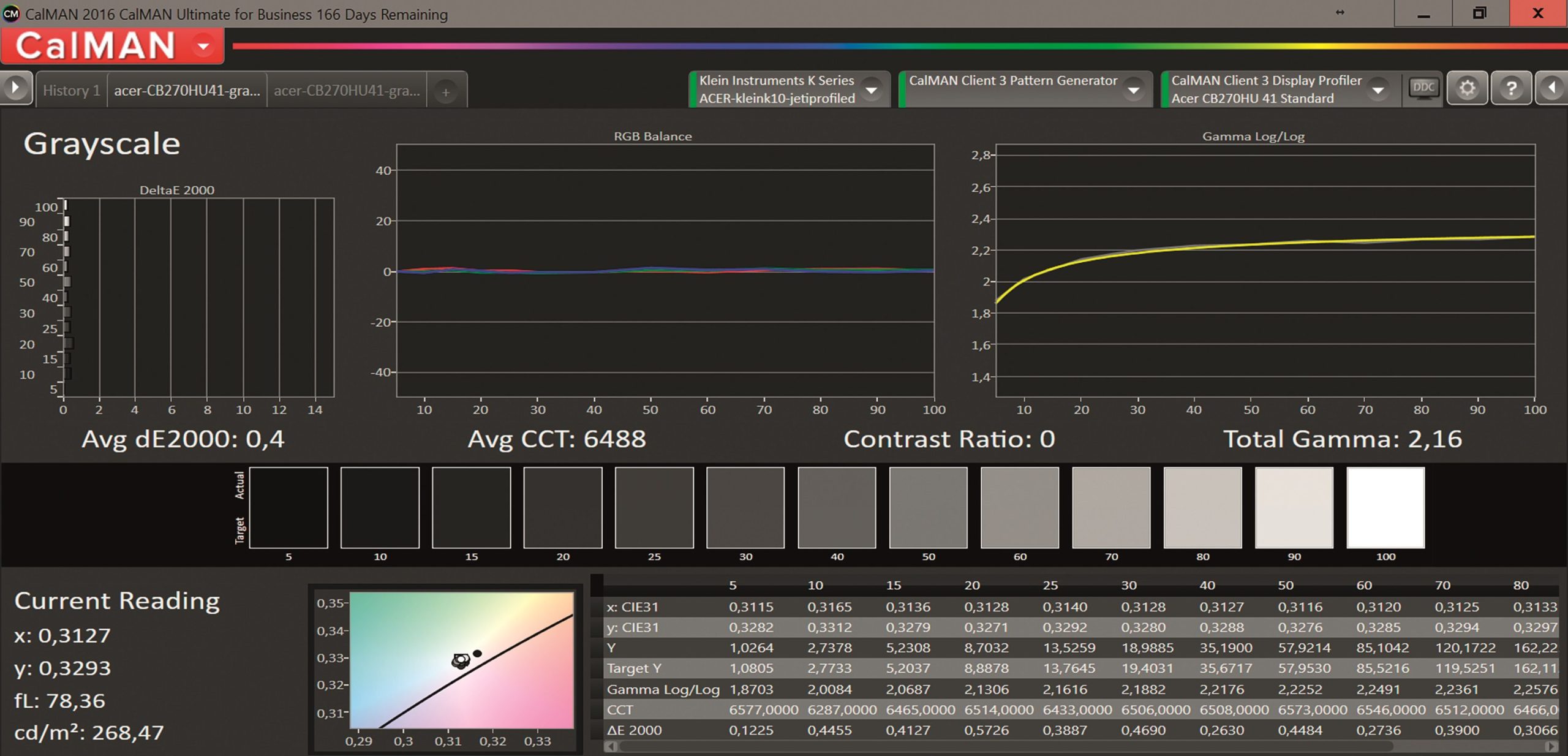

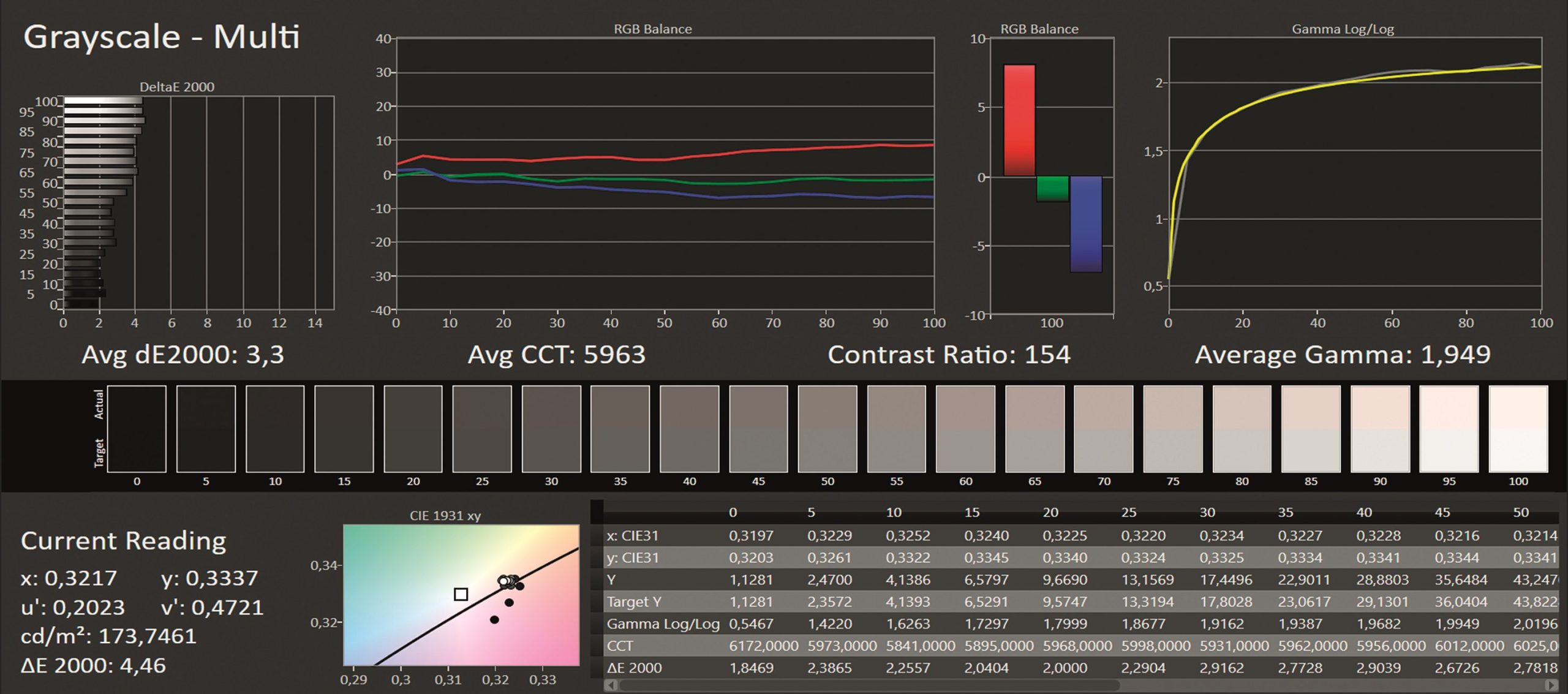

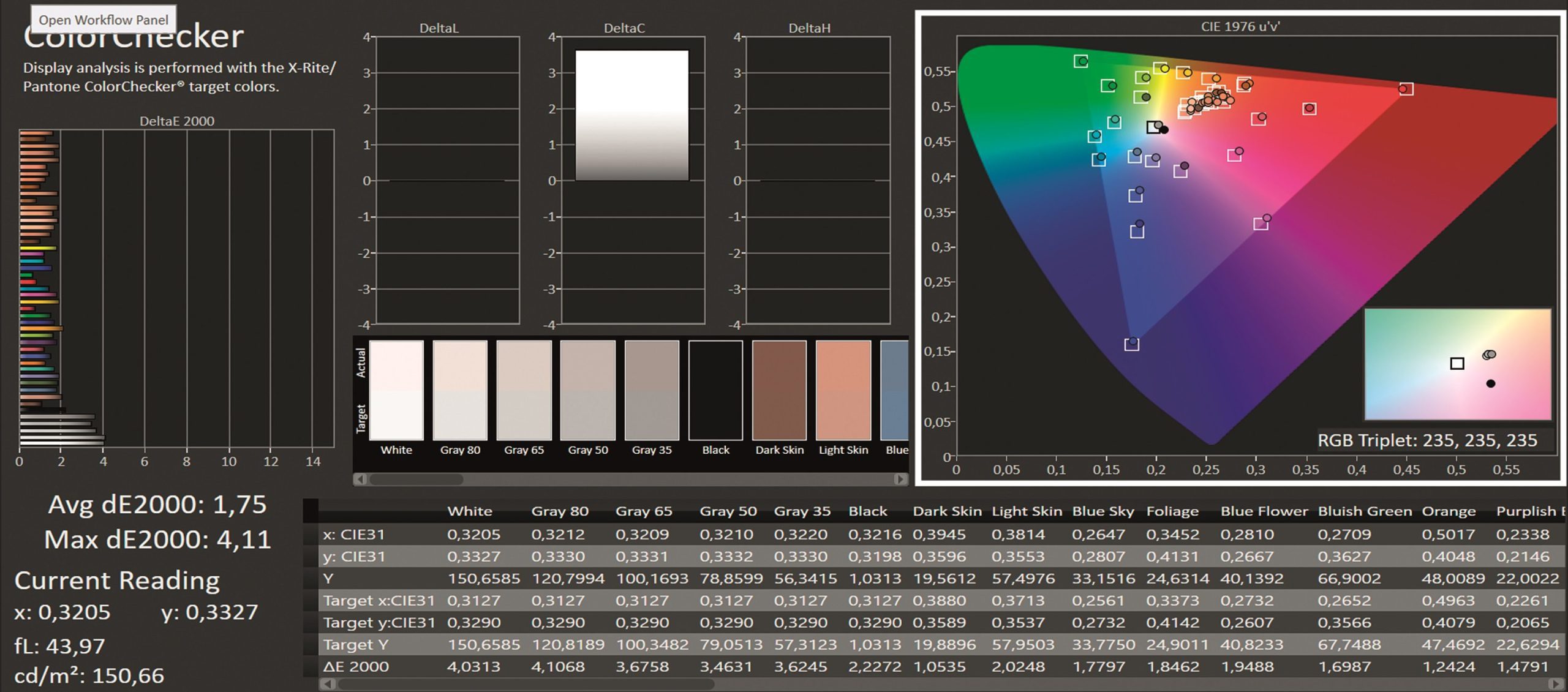

As I mentioned in the article on the Calman software, the consumer-level calibration packages are inexpensive and therefore an incentive to buy, but the investment is not worth it if you don’t know that the device is dramatically off colour (e.g. far too blue, which is not uncommon). In this test, the calibration clearly made the colour reproduction too red and thus worsened it. The initial situation was surprisingly good for a Mac.

Not necessarily comprehensible for a layman, who thinks he has done everything right and insists that his display is the reference for the colourist – and he is at a loss for words as to what he actually wants to say when thinking about this situation. But there are alternatives – you can read more about the Calman Spectracal 6 bundles, if a suitable measurement profile exists for the display, in the Calman report, and the large measurement device test can be found in DP 01:2014 or downloaded free of charge at www.digitalproduction.com.