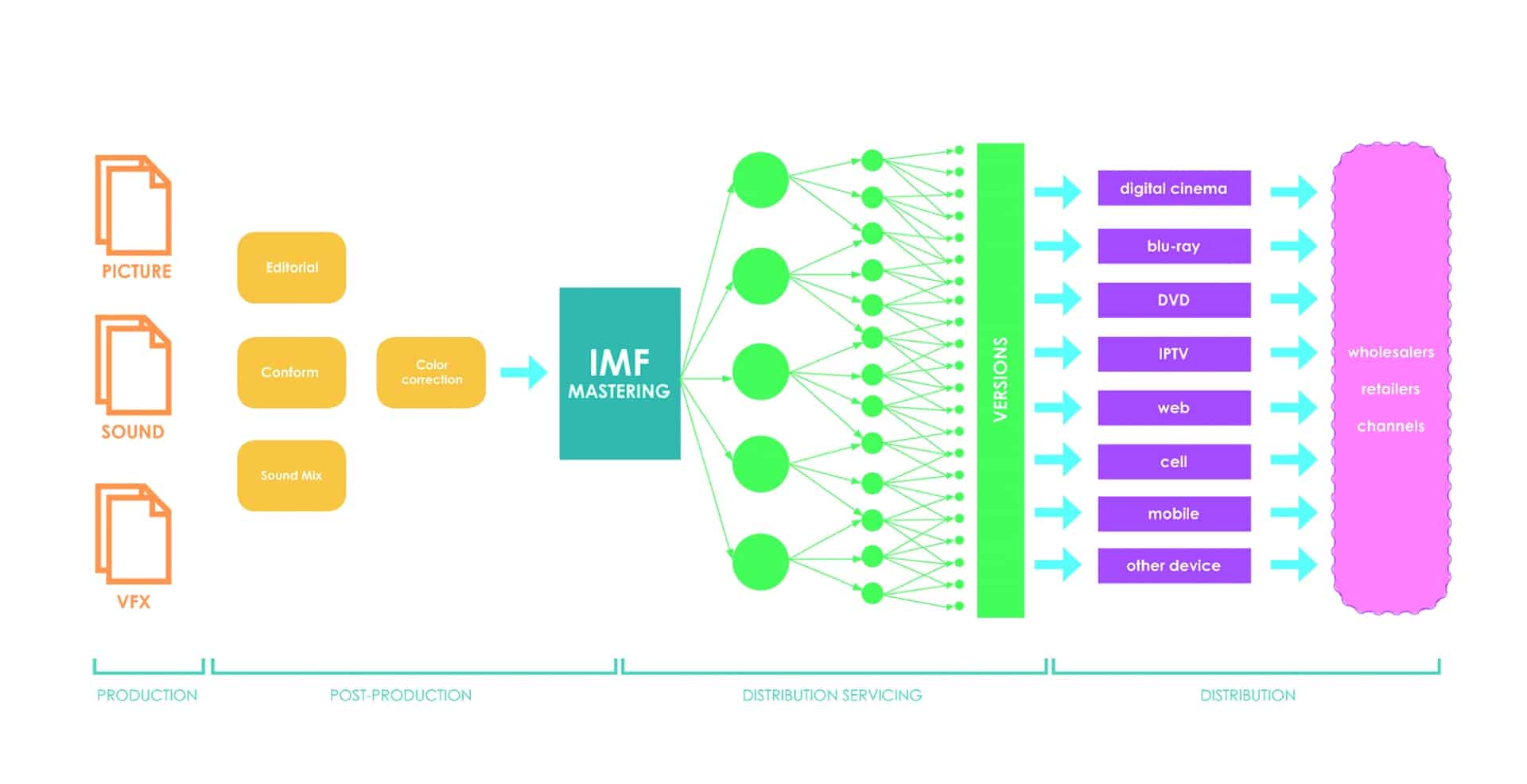

In the beginning there was a problem – and in fact it was already there at the very start of international distribution: Because international distribution goes hand in hand with a thousand different versions of a film being needed. So why did our industry need another complex format? That’s why.

Different final formats, different language versions, edited versions, subtitles, output devices – in short, an almost unmanageable number of tapes and/or file formats, including chaotic content and metadata management and high storage space requirements.

IMF is now supposed to solve all these problems: a format that contains all the required versions, is easier to handle and also saves storage space. The discussion about what such a format should look like began back in 2007, and in February 2011 the USC Entertainment Technology Center finally adopted the IMF Specification 1.0 – one month later the SMPTE Working Group 35PM50 was launched, from which the various IMF applications later emerged (more on this in a moment).

The following points were clear from the outset: IMF was to replace tapes as a storage medium – a fact that had already taken place even without IMF. Next, it was to contain all variants and versions of the content – in other words, in addition to the original version of the film, all available language versions, sound mixes, subtitles, edited versions, etc..

The required storage space should be minimised by two mechanisms: Firstly, video compression should be available. Secondly, content should not be stored twice. Until now, this was inevitably the case: If a master was created for the American market – let’s say as ProRes 444 incl. stereo and 5.1 mix – a second master was created alongside it, for example for the German market, which took up the same amount of storage space. Both masters were approximately the same size, as the video takes up the lion’s share of the storage space – and this is predominantly the same for both masters – apart from the few places where localised titles can be seen. Added to this are the different cut versions.

IMF also solves this problem elegantly: only one master video track is saved in the IMP (Interoperable Mastering Package) and all versions reference this master track and only save any modifications (e.g. localised title sequence) as actual video data.

In all of this, IMF should utilise existing standards – such as the MXF container, the XML format, or JPEG 2000 compression. The bottom line is that IMF is not an acquisition or live production format – no camera in the world will spit out IMF. It is also not an intermediate format like ProRes, which can be used for editing and colour correction. IMF is something like a final “Grand Master”, which is primarily intended to facilitate distribution (business-to-business).

Applications – the flavours of an IMP

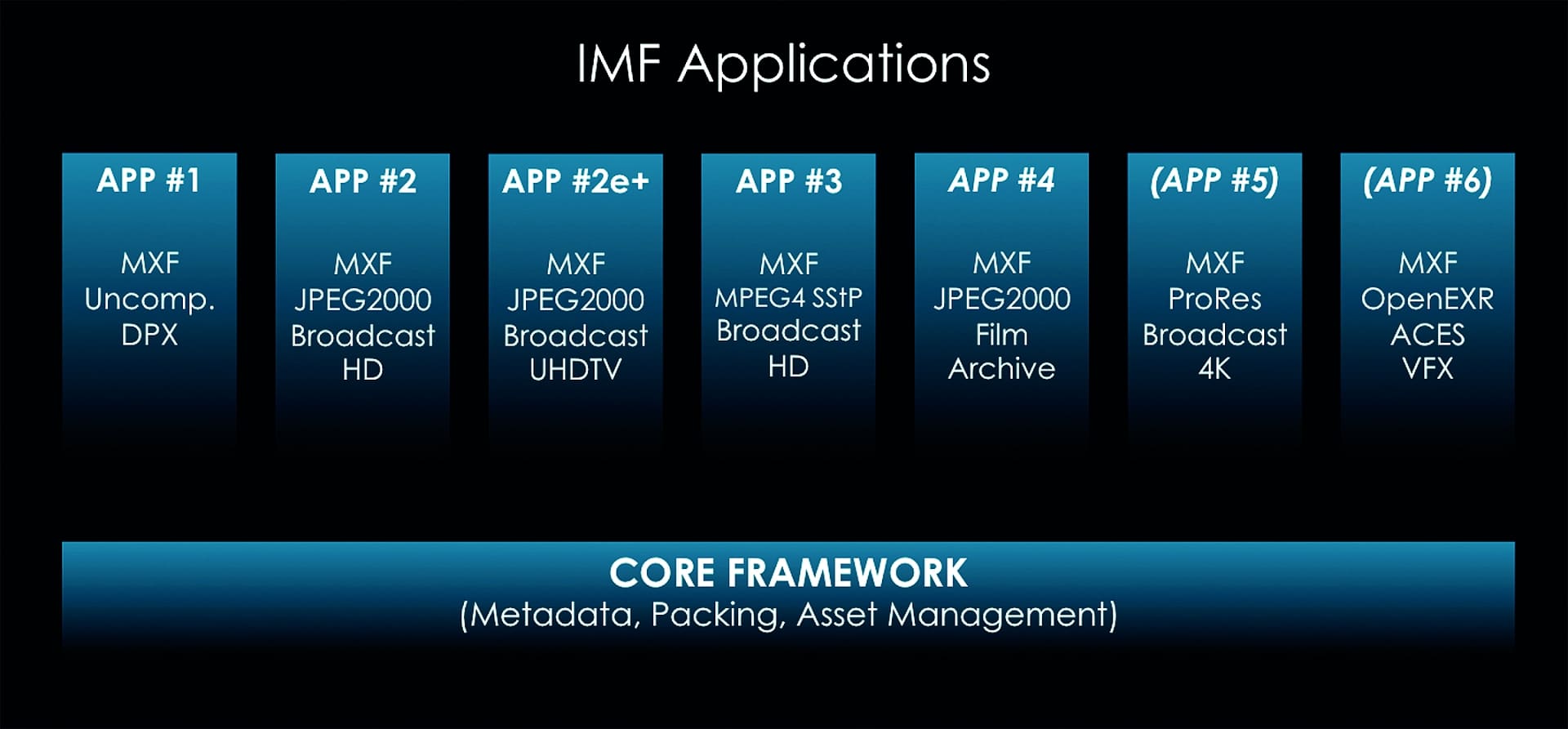

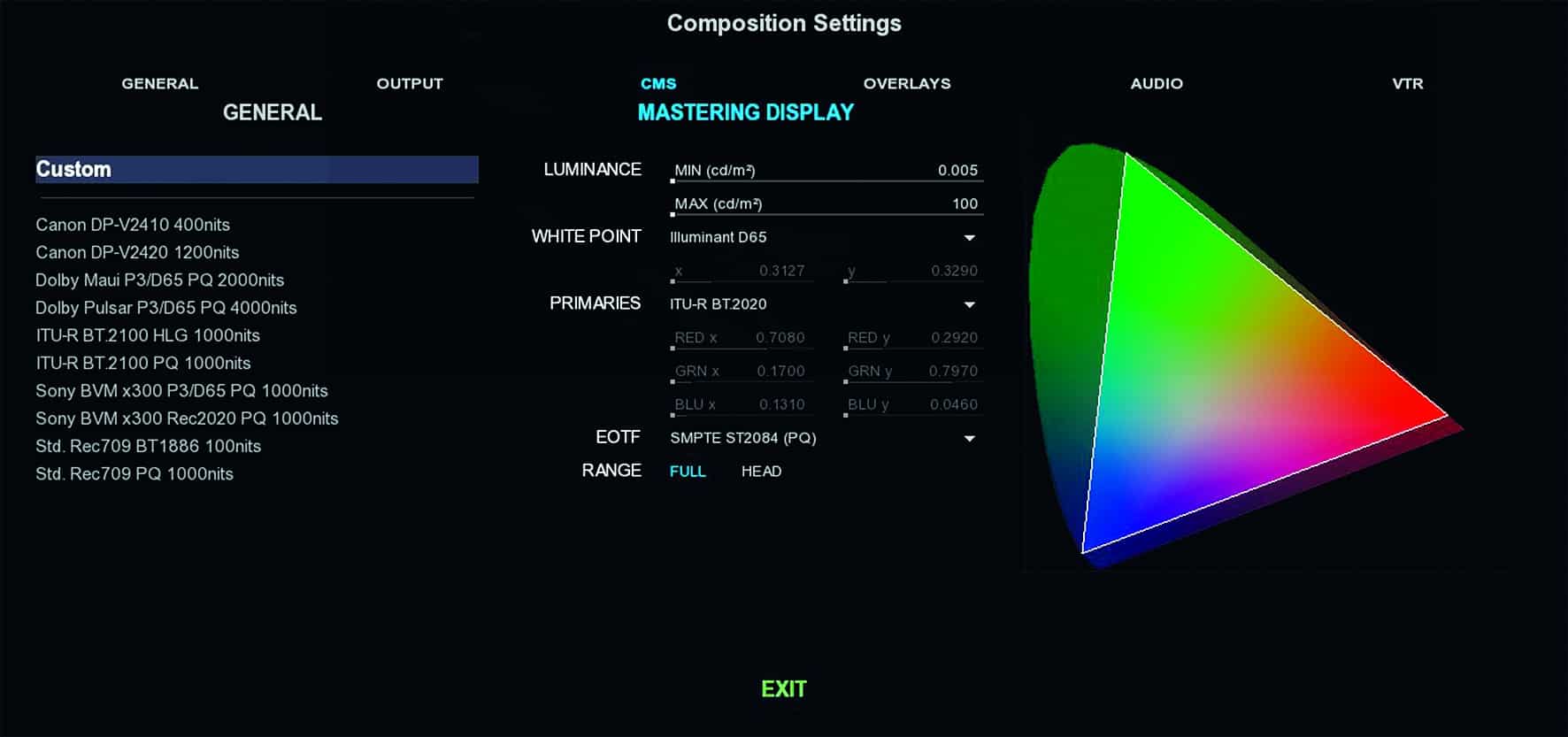

Before we look at the inner workings of an IMP, let’s first talk about what are known as IMF applications. IMF applications (apps for short) describe different variants of an IMP for different areas of use, but they all use the same basic structure. Different features of the various apps are, for example, compression, colour space, quantisation and resolution (see info image below). So before you start creating an IMP, you first need to find out which app is specified in the customer’s delivery specifications. App 2e (e for “extended”, for “even more extended”) is currently the most commonly used, as it essentially describes the features for today’s network distribution à la Netflix: AS-02 MXF container, lossy and lossless JPEG 2000 compression, 12/16-bit RGB colour depth, Rec. 709 or Rec. 2020 colour space, max. 4Kx3K resolution, HDR and uncompressed PCM audio in an MXF container.

App1 is the unicorn among the applications – actually, it is not an application as such, but rather a deceptive package for archives that have something against video compression and container formats everywhere and therefore prefer to save their content in uncompressed DPX or TIFF sequences.

App3 is Sony’s more or less failed attempt to establish its own IMF standard based on HDCAMSR – presumably nobody except Sony uses this standard.

App4 is aimed at distribution from film archives. App4 supports resolutions of up to 8K and archival frame rates (such as 12 fps), but is only permitted in the XYZ colour space in 16-bit JPEG 2000.

Two more apps are currently in the works: OpenEXR- and ProRes-based IMF. Both are to be adopted as standards within the next few months (they appear in the info box as App5 and App6 – these names are likely, but have not yet been finalised). The EXR IMF is intended to facilitate the exchange of VFX in the ACES colour space, while ProRes is mainly of interest for the broadcast sector – in both cases, an MXF container is again used for the video data. The reason for the introduction of the two formats is simply that existing content does not have to be re-encoded, but simply re-wrapped, which is much faster and requires less processing power when creating IMPs.

What’s in the box

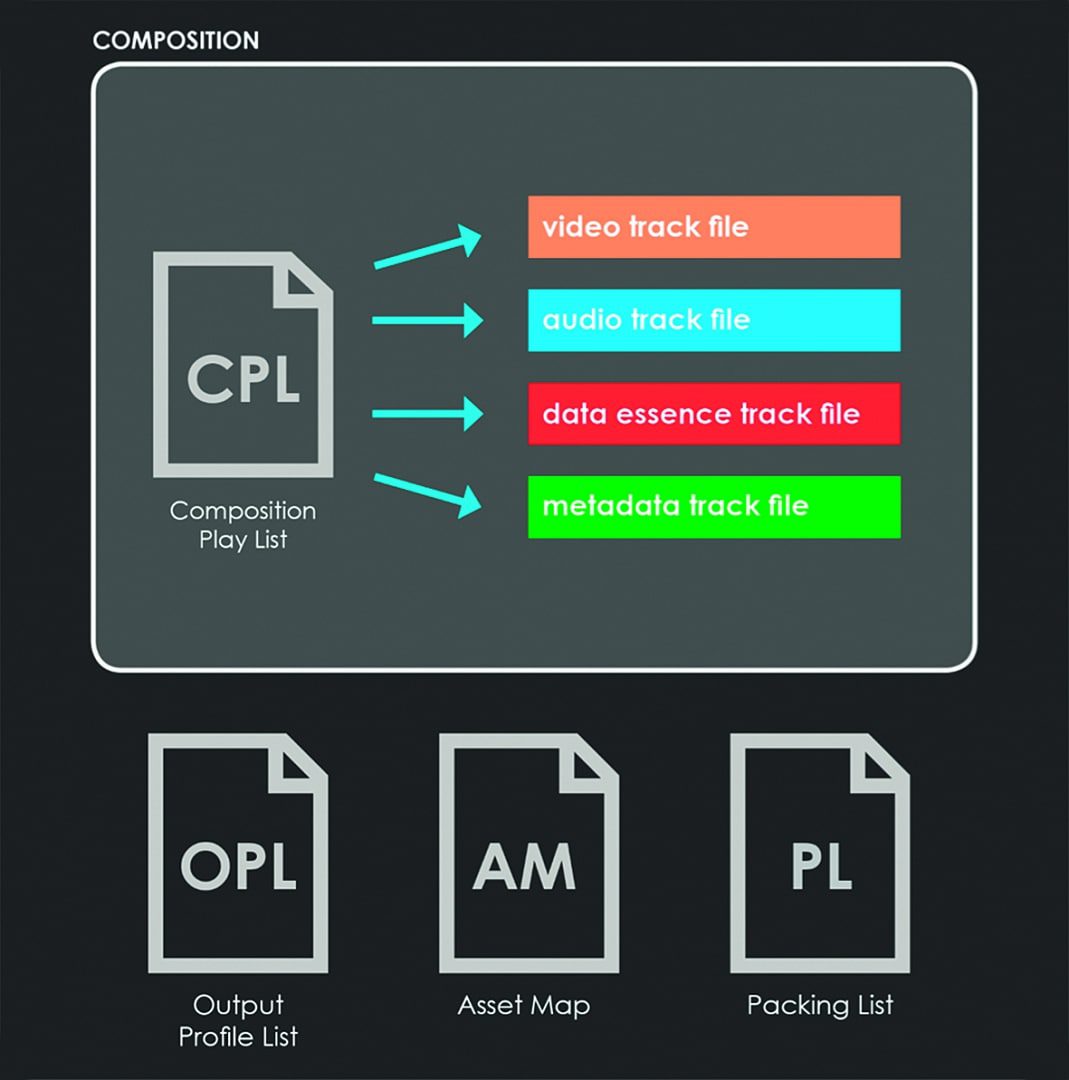

But now to the insides: On the outside, an IMP has taken over quite a lot from a DCP. Similar to a DCP, an IMP is a folder with a series of files – audio and video are stored separately in the form of MXF files (with the exception of App1, which is not an app). There is also a series of XML files. What does not exist is DCP-like encryption using KDM.

Firstly, the MXFs: As already mentioned, video and audio (and subtitles) are stored in separate MXF files so that they can be combined flexibly. Specifically, all video segments are each stored in their own MXF: i.e. the 90 minutes of the original film are in one MXF. The 2 minutes of the German title for the German version are in a separate MXF and so on.

There are various options for saving the sound in MXF files. Normally there is one MXF per soundfield. A soundfield is a compilation of various related audio channels. For example, the 6 audio channels for the German 5.1 mix represent a soundfield (German 5.1), the two stereo channels for the original English dubbing represent another soundfield and so on.

The XMLs perform various tasks: Firstly, there is ASSETMAP.xml – in both a DCP and an IMP, everything and everyone is referenced by its own UUID (Universally Unique Identifier) in the file header. The ASSETMAP.xml assigns the appropriate file name to each UUID within the IMP.

Next comes the packing list (PKL_name_of_pkl.xml). Related files are listed here based on their UUID – this allows a server to quickly find out whether all assets for playing a specific version are actually available. An IMP that contains an English and a German version could have two PKLs: One PKL that contains all the UUIDs needed for the English version and another PKL that lists the UUIDs (and therefore files) for the German version.

Finally, there is the composition playlist (CPL_name_der_cpl.xml). As the name suggests: a playlist. A CPL is similar to an EDL (Edit Decision List). Here, the various assets (video, audio and subtitle files) are referenced using their UUIDs and a kind of timeline is built from them (e.g. German video track, but shortened cut version, together with German 5.1 mix). The nice thing about CPLs is that they do not use timecode for the “cut”, but edit units, which are much more precise and flexible.

Edit units depend on the format used: for video, edit units are simply frames, for audio they are samples. The CPL then works like this: Source clips are so-called “resources” and are referenced using their UUID. Each resource has a so-called entry point and a duration (both in edit units), which are used to set the counterparts to source in and out of an EDL. A sequence is then built from several resources, which in turn represents a segment within the playlist.

This basically provides all the ingredients for a simple IMP. Optionally, two more things can be added: Subtitles and OPLs. OPL stands for “Output Profile List” and describes a series of macros that are used for automated transcoding, for example. Here, a transcoding software is given instructions on how to create a German HD version with a 5.1 mix from multilingual 4K content, for example. The OPL is also saved as an XML file in the IMP (OPL_name_of_opl.xml.). However, OPLs are currently hardly ever created, requested or required, as there is currently a lack of support, market and development resources.

Subtitles must be in TTML format (Timed Text Markup Language) and are also wrapped in an MXF container. TTML enables high-quality rendering of subtitles for cinema, TV and OTT (over-the-top) content and is also fully compatible with non-linear content (i.e. can also be “cut up” by a CPL together with video and audio). Metadata from older subtitle formats such as CEA 708 (mainly used by US broadcasters) or EBU STL are also supported by TTML.

As future-proof as TTML is, it is also difficult to implement – support for this format is unfortunately not yet so advanced, as it is a fairly comprehensive format – IMF therefore uses a slightly slimmed-down version: IMSC1 (Internet Media Subtitles and Captions 1.0). But all in good time.

reference value (usually 1OOO nits), the graph turns red.

Full, Version and Supplemental IMPs

Not all IMPs are the same. Like any complex format, IMF also has various variations and subtypes. A full IMP contains various, if not all, versions of a film in picture, sound and subtitles – it is the “grand master” IMP, so to speak. If you now take a look at broadcast distribution, it quickly becomes clear that there is little interest in distributing full IMPs across the globe. What is an Austrian TV station supposed to do with the Israeli language version and Lithuanian subtitles? So what do you do? You create a so-called “Version IMP” from the “Grand Master”, which only contains the picture and sound version for the Austrian market – perhaps with optional subtitles in German and English.

That leaves the Supplemental IMP. Let’s assume that an IMP with a German picture and language version has already been distributed to broadcasters in Germany. Unfortunately, the subtitles were not yet ready at the time of distribution. A supplemental IMP is therefore created, which only contains the subtitles and a CPL, but which references the original IMP with the picture and sound data. This means that the supplemental IMP requires the previously delivered version IMP in order to be played. A similar scenario is a newly released director’s cut, new or additional language versions or modified opening and closing credits. Of course, it is also possible to add a Supplemental Package to a Version or Full IMP at a later date and send it as a single package.

Version and Supplemental IMPs therefore offer the greatest possible flexibility – the disadvantage of the story, however, is that IMF is not necessarily suitable for archiving. Not only because everything gets out of hand above a certain amount of Supplemental and Version IMPs, but also because

Archives do not like video compression and container formats such as MXF. Compressed data can hardly be recovered from defective data carriers in an emergency – that’s why archives usually fall back on something IMF-like, which comes uncompressed in the form of TIFF or DPX sequences and otherwise also looks like an IMF – but isn’t really one (there it is again, our hated chip child App1).

What it takes to create an IMP

So, enough about the inner workings of an IMP – what do you need to create one? First of all, the right hardware. No matter which software you use, they all use GPUs to decode and encode the JPEG-2000 video – so powerful graphics cards are an advantage. An Nvidia GP100 can achieve approx. 100 fps 4K JPEG 2000 encoding – but similar figures can also be achieved more cheaply with a few Geforce cards. However, the storage should not be ignored, as the source material is usually uncompressed and therefore bandwidth-hungry – so if the storage is not fast enough, it cannot deliver the data as quickly as the GPU could encode it and becomes a bottleneck. The CPUs are currently not given quite as much weight as the graphics cards, but the CPUs have to shovel the data from the storage to the GPU fast enough – 24 physical CPU cores should be enough for 4K content. However, the upcoming ProRes application should be kept in mind: ProRes is decoded and encoded entirely on the CPU. There is no upper limit for everything, GPU, CPU and storage – depending on how fast you want to decode and encode, you can increase as far as the machine allows. On the software side, you don’t have too many options these days.

The entry into the IMF world is made with Fraunhofer’s EasyDCP (cost: 6,545 euros incl. VAT) or Innovative Pixel’s FinalDCP (3,569 euros incl. VAT). This gives you a software solution for DCPs and IMPs – but both lack certain mastering functions such as the creation of cut versions, validation, soundfield creation and the like. DVS Clipster also has DCP and IMF mastering functions: If you have one, you can of course make use of them. The disadvantage of Clipster, however, is its outdated architecture, which makes it difficult to keep up with the rapid pace of development. Whilst the competition is already fully committed to GPUs, Clipster owners still have to deal with the slower, less flexible, proprietary and not exactly cheap hardware. This brings us to the two main players in the field of IMF mastering: Marquise Technologies MIST and Colorfront Transkoder. Both are a comparable burden on the wallet in the 5-digit range. Transcoder is mainly sold as a turnkey system, but is also available as software-only.

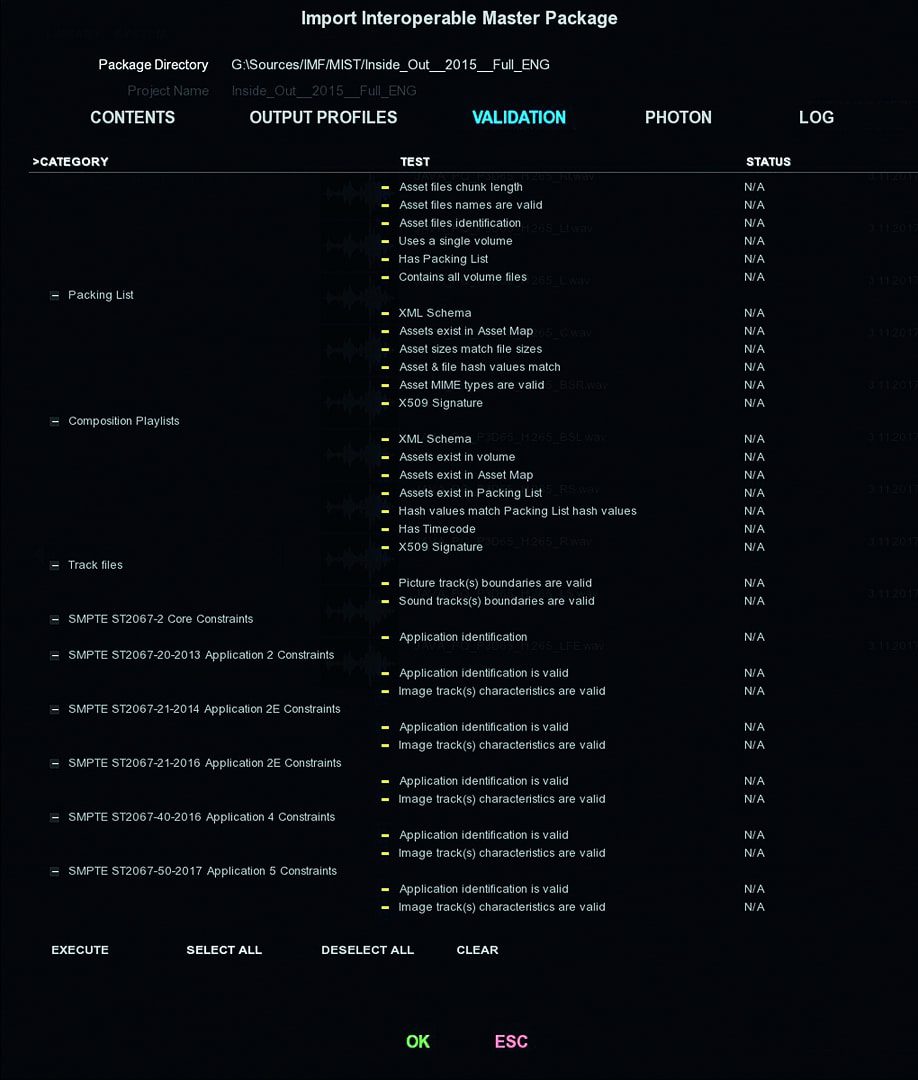

The situation is similar with MIST, but there is a basic software version to which you can add various optional add-ons, e.g. DCP mastering, IMF mastering and HEVC rendering, whereas Transkoder comes with everything from the start. MIST is available as a Windows-only package, while there is also a Mac OS X version of Transkoder in addition to the Windows version, although this does not have the same range of functions as the Windows version due to the OS and is largely unusable for IMF workflows. Both systems decode and encode JPEG 2000 on one or more GPUs. In addition, both offer a DCP and IMF validation function, which subjects an existing IMP to a series of tests to ensure that the respective IMP is also standard-compliant.

Both Transkoder and MIST also have a range of colour grading, editing and HDR management tools as well as colour management and SDI output. There is also a player-only version of both manufacturers (also including validation functions), which are designed to carry out quality checks of IMPs. If you would like more information or a trial of either system, please contact the respective reseller here in Germany (DVE-AS for Colorfront, DVE-X for Marquise Technologies) for advice. Many thanks at this point to Dan Tatut from Marquise Technologies for his help in obtaining information for this article.