But before we get to see excerpts from the film at the lectures, we sat down with director Pascal Schelbli and VFX supervisor Marc Angele and let the story of “The Beauty” drift past us. And if you want to see the whole film in advance, you can find it here in full length on the Filmakademie’s YouTube channel: is.gd/filmaka_beauty

DP: What has happened to the film since Animago 2019, where “The Beauty” won the Jury Prize?

Pascal Schelbli: The film has had an incredible festival tour. In addition to countless awards such as the Young Directors Award in Cannes and the VES Award in LA, it won the Student Academy Award that crowned everything. This attention has certainly played into the hands of the online release and the film has also been doing the rounds on the net. In addition to the fact that the film generated orders for us freelancers, we also made some very interesting contacts from all sectors.

Marc Angele: It’s really great what we were able to experience with the film. A lot of people have now seen it, especially in our industry. People keep asking me about it and I’m always surprised where it’s been seen. Personally, however, the highlights for me were the Visual Effects Society Award and Animago. We were able to experience these two awards live, before Corona. The fact that we can now also be FMX trailers is of course mega!

DP: If you were to make the film again, what would you change?

Pascal Schelbli: I think we would have done everything in Houdini, including rigging and rendering. But we were both very much at home in C4D at the time and that’s why we brought everything together there.

As the film mainly takes place below the surface of the water rather than above it and the scenes each consist of a light source that is refracted by the surface of the water and hits the objects, there’s not much new in terms of rendering, apart from more powerful CPUs and GPUs. However, the last shot with the waste could have been made a little easier. For example, lidar scanning could have been used to scan the rubbish on site with a mobile phone instead of having to illuminate all the objects in the studio and then run it through the rather complicated photogrammetry process at the time. This would have allowed us to generate more assets more quickly and then simulate them completely. This would have saved us one of three shooting blocks. On the other hand, the power of real filmed material should not be underestimated.

Marc Angele: Basically, there aren’t that many things that I think we would do differently today. As Pascal has already said, back then we rendered everything in Cinema 4D with Arnold. Today, I would definitely do it in Houdini. Sometimes we had quite a lot of problems transferring all the attributes from Houdini to C4D. This was particularly difficult with the flip-flop swarm. We had to come up with a few workarounds. Even just getting the velocity cleanly to Arnold via C4D was not easy. I still think Cinema 4D is a great tool and it has simplified a lot of things, but managing things like that was pretty time-consuming back then. What’s more, we would certainly have replaced or added one or two tools today. I would rather do it with Renderman today, but that’s just a matter of taste.

DP: When was the last time you went diving? And what stuck to your fins?

Pascal Schelbli: The last time I actually dived with a tank was in St Malo in France during our last filming block (2019). Of course, I’ve been snorkelling here and there in Switzerland or Italy, but it’s not comparable to such a fascinating underwater world that you can dive into for an hour. I’m thinking about becoming a “rubbish diver”. They volunteer to clean up the lakes and rivers in Switzerland once a year.

But yes, who would have thought when I got my diving licence in Belize in 2013 that I would need it for my graduation film. And I think that’s what stuck with me. At some point, The Beauty was a thought in my head and became a finished product and it’s incredibly motivating that you can create something “tangible” from ideas and reach people in the form of images or films.

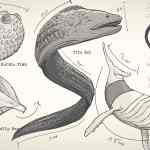

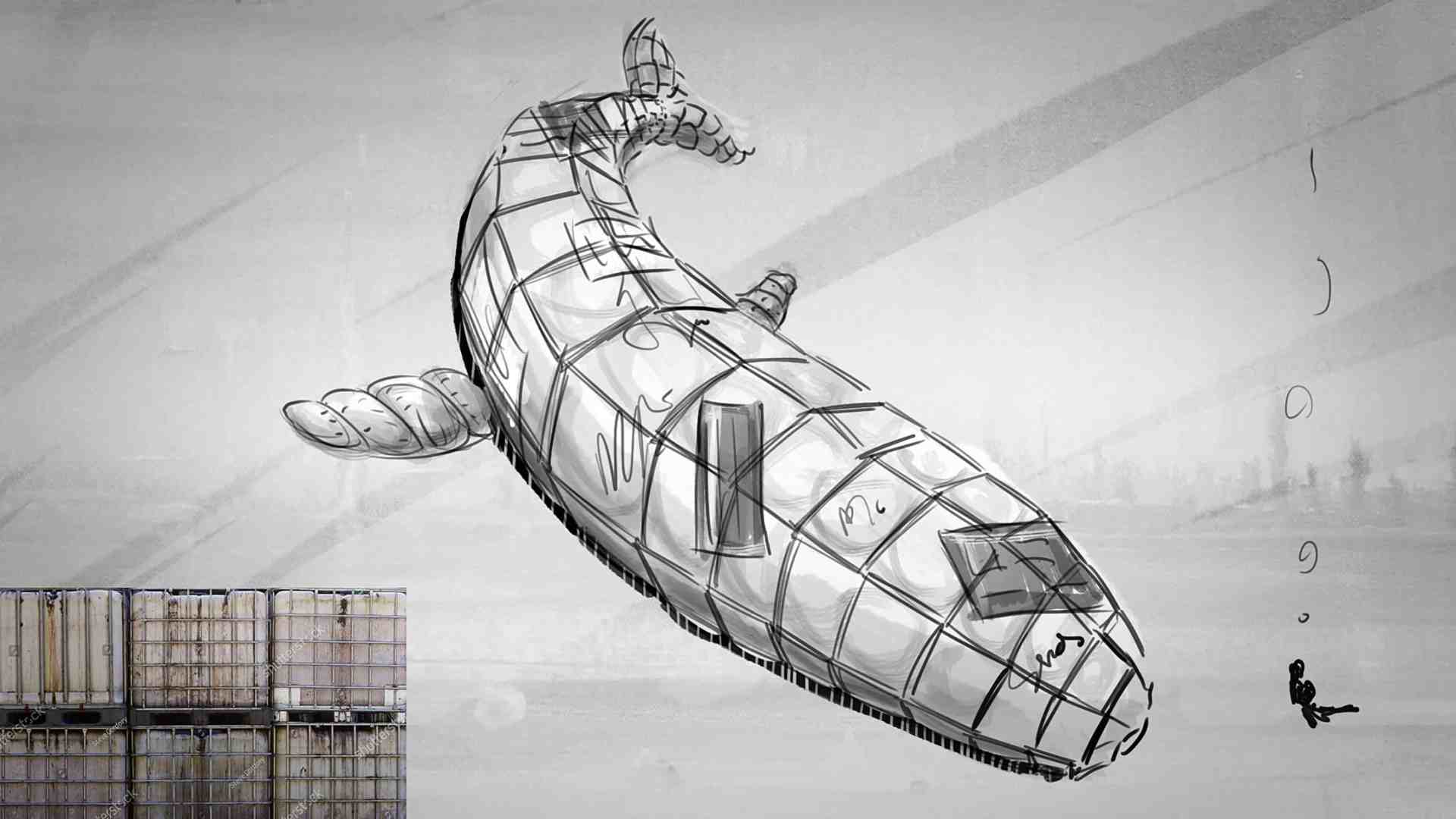

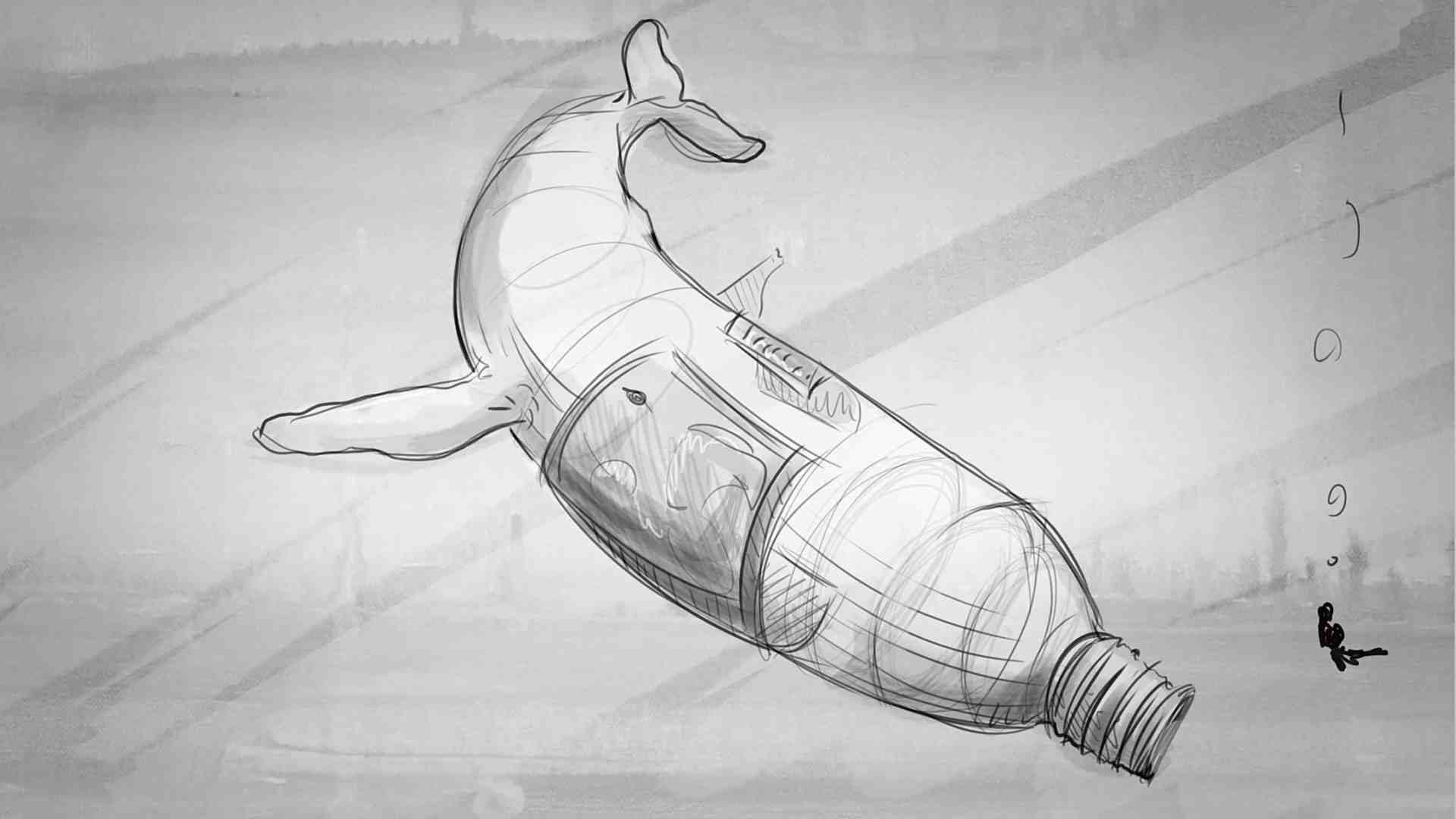

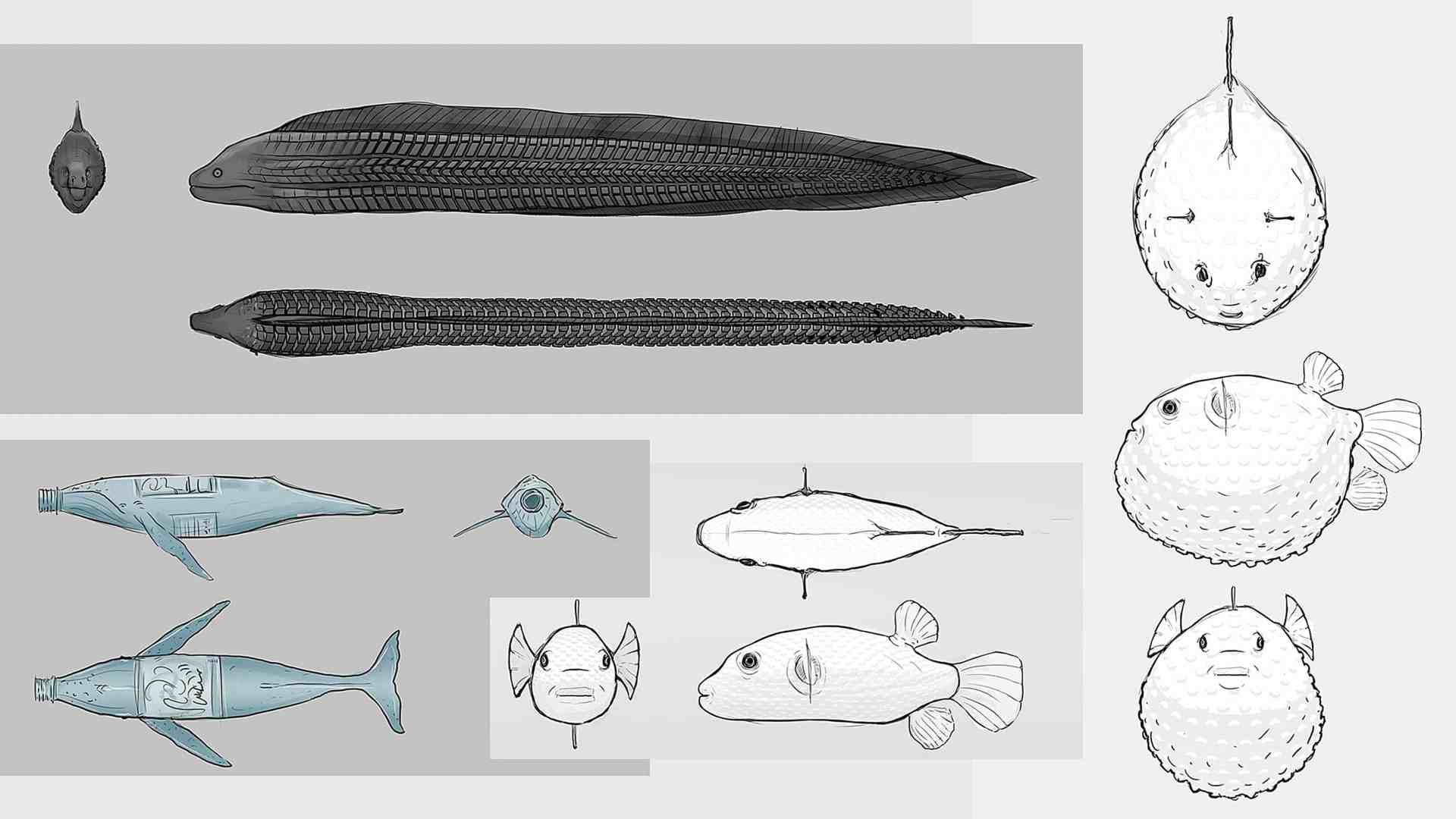

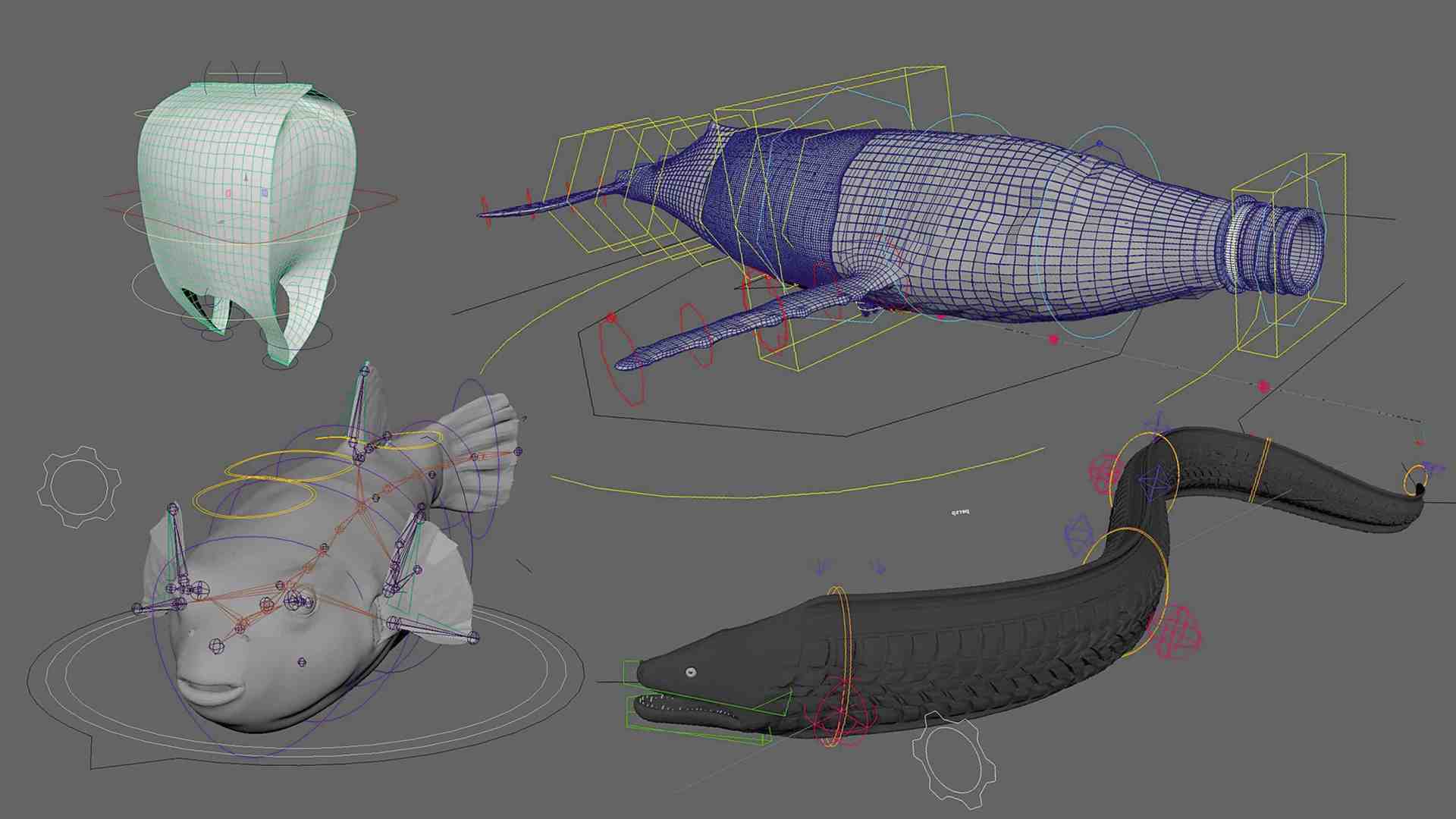

DP: The models still look great – how did you design the animals?

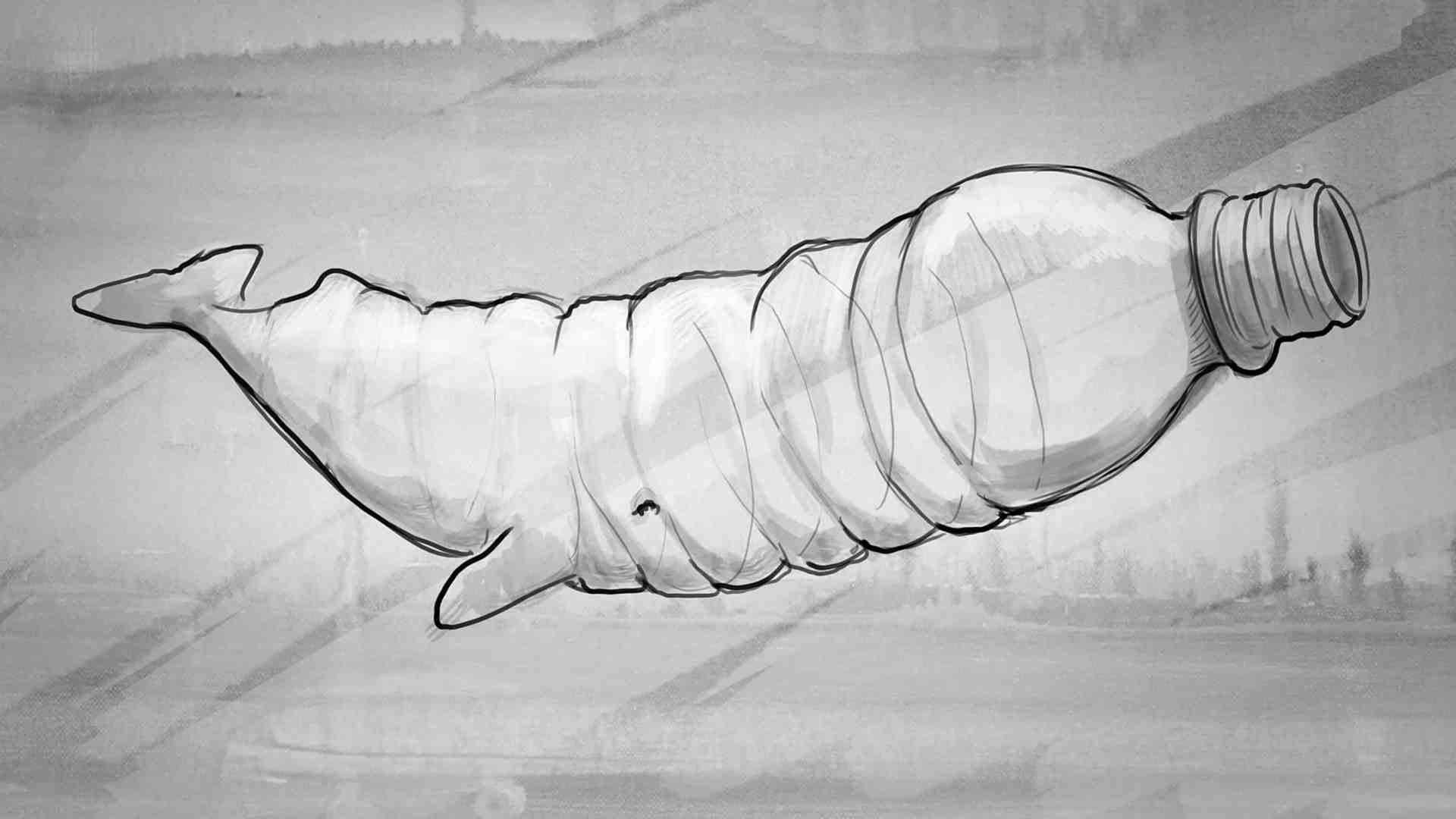

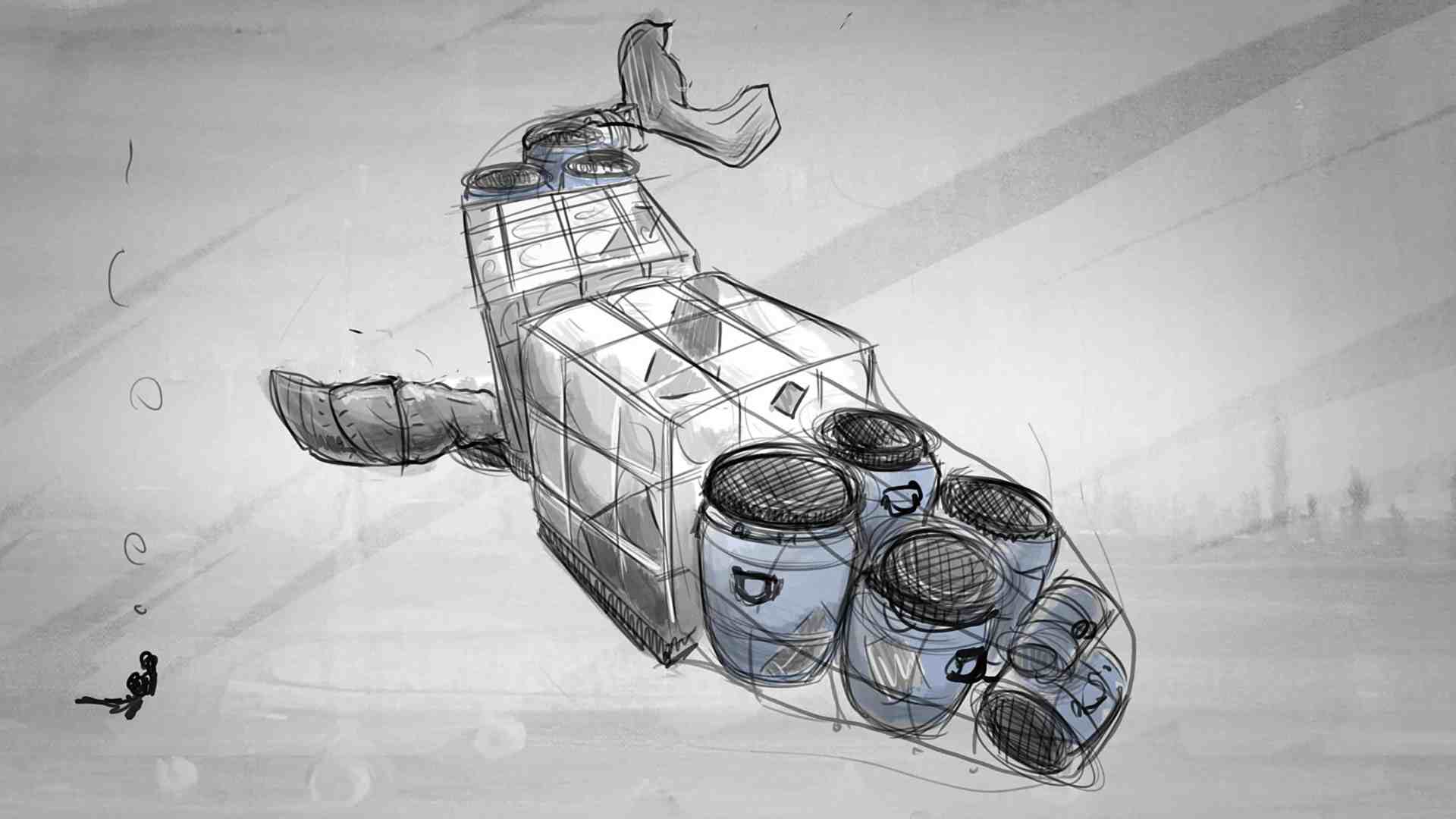

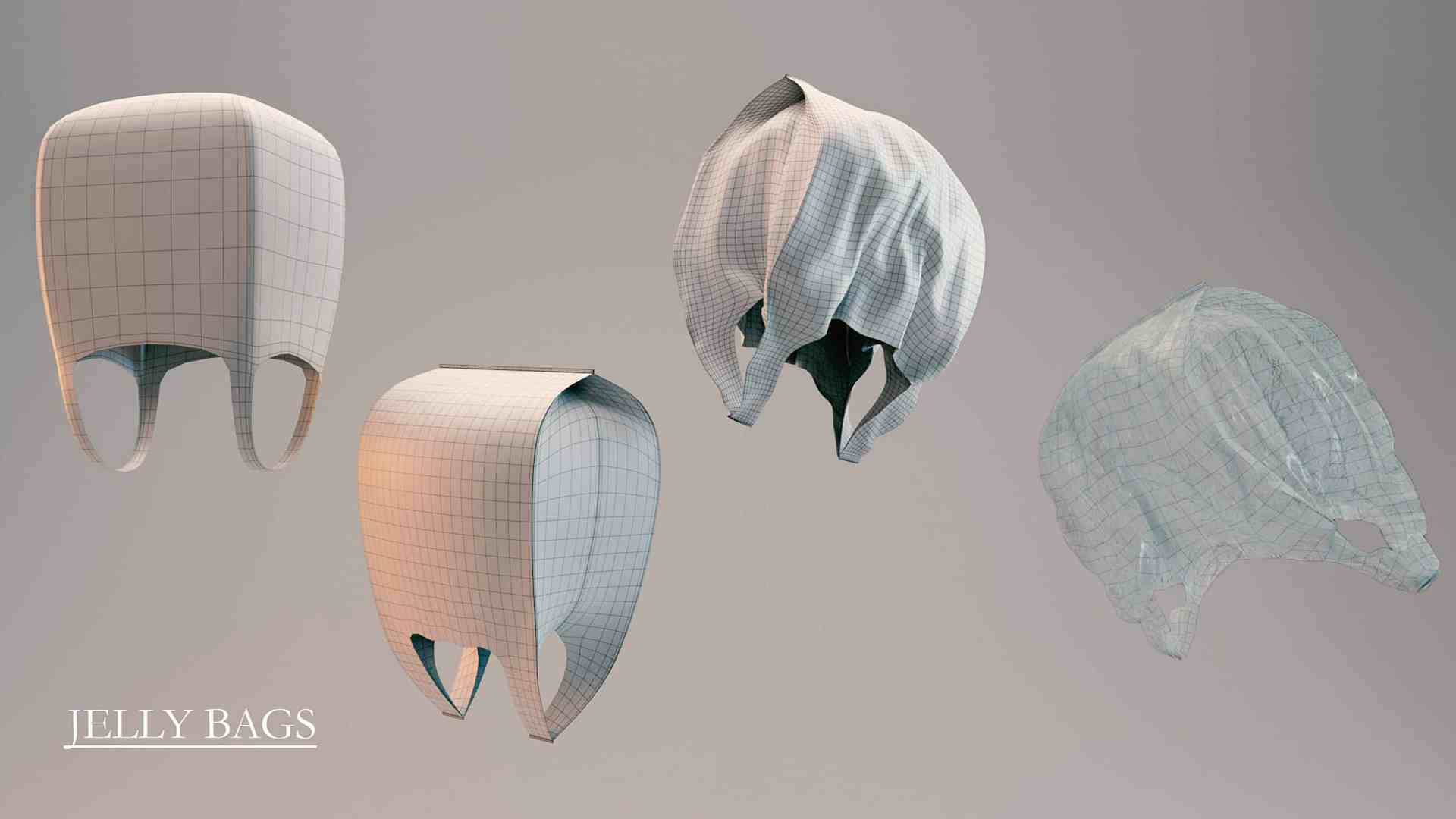

Pascal Schelbli: I can’t give you an exact number, but there were definitely a few rounds. It all started with a picture of a ray with a flip-flop flap on its back. Then came the moray eel, which was finalised very quickly. With the whale I had tried different types of bottles, with the bag the decision was with or without tentacles, the pufferfish almost ended up being a detergent container and the straw was first given a seahorse fin.

Marc Angele: “Realising Pascal’s designs in 3D was quite tricky, especially with the transparent creatures. We first had to find out how everything would behave underwater in order to model it correctly. The transparencies weren’t easy to create either.

We went round and round to find out which areas should be opaque or transparent so that the character and its expression could still be easily read. This was particularly difficult with the pufferfish. We decided to make the upper part a little more opaque and yellowed so that its face could be recognised at all. So every creature had its difficulties. The challenge with the whale was to find the right scale for the textures. A whale is huge, but the textures should look like a small PET bottle. It took us 2-3 versions to get that right.

DP: And how did you decide which combinations of creatures and rubbish you wanted to create?

Pascal Schelbli: After googling pretty much all existing plastic parts and known sea creatures and trying to combine them, the ones that made it into the film were the most exciting combinations.

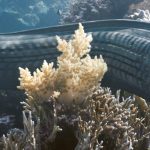

DP: And with the moray eel, were you able to simply throw the tyre structure onto the surface?

Pascal Schelbli: No, unfortunately it wasn’t that easy. However, the moray eel was pretty straight forward and the first object that was finished. In terms of art direction, there wasn’t that much to do here either, as my character designs were actually already very detailed and we shot reference images of each creature underwater.

Marc Angele: From a lookdev point of view, the moray eel was by far the easiest creature. Fynn Grosse-Bley, our modelling artist, had already worked in a lot of detail. All I had to do was brush a bit of dirt on it and tweak the shader a little. However, the moray eel had the biggest appearance in our film with five shots and was therefore not easy for rigging and animation. Noel Winzen, our Creature TD, really got stuck into it.

Noel Winzen: The biggest difficulty in rigging was the complex movement pattern of a moraine. The undulating movement had to remain as “art-directable” as possible, which is why a procedural solution was not an option for us. At the same time, the movement could not simply stop when all controllers had reached the end of the moraine. The solution was to create a setup in which the controllers are position-unbound, so the order of the controllers doesn’t matter and in this way we could simply guide each controller back to the beginning as soon as it reached the end. From a technical point of view, this meant that we could find the next point (u-value) on the spline for each controller and use this 0-1 value to control a colour ramp, whose colour output could then in turn control the rotation or translation. We were also very lucky to discover and film a real moraine during our shoot. Using this footage, we were able to re-animate the movement of the moraine one-to-one and see if we needed to make any improvements to the rig. In the final film, we reduced the wave-like movement again to give the impression that the moraine was made of a rubber tyre material.

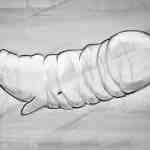

DP: The whales and the puffer fish have transparent materials under water – how did you manage to make them realistic?

Marc Angele: Texturing and shading was one of the most difficult tasks of the project. Under water there is a different IOR for materials than in the air, so all reflections behave completely differently. For example, a surface underwater reflects 100 per cent from a much steeper angle, so the Fresnel effect is much more visible. Fortunately, we took a lot of reference material with us when we were filming in Egypt and were able to observe the effects very well.

In the end, however, we didn’t quite stick to the physically correct values, as our viewing habits are different and the resulting effects would probably have confused the viewer. When modelling, however, we absolutely had to stick to reality. After a lot of back and forth, we realised that we couldn’t fake too much in the shader. The models really had to be modelled exactly as they would be in reality – double-walled, for example. For the pufferfish, we modelled a geo for each bubble, which was given an IOR for air. This allowed us to precisely control each element in the shader. However, the additional geo didn’t really make the simulation of the inflation any easier.

DP: And the rendering was a challenge?

Marc Angele: Once the creature had been textured and shaded for the first time, the effort involved in the individual scenes was no longer so great. In the beginning, we created a light rig to simulate the underwater world with sufficient control. The rig consisted of a water surface with wave displacement, an HDRI sky that only lights up above the water surface, a lot of environment fog below the water surface, a directional light for the sun and a light with a caustic texture for the typical water effects. We shot the Caustic Texture in Egypt on the bottom of the pool of our hotel, which later became one of the most important assets.

We were able to simply apply this light rig to all scenes, make a few adjustments and render directly. The rendering itself took very different lengths of time. The scenes with the transparent creature took a very long time because we had to turn up the ray depth extremely high. The other scenes were rendered fairly quickly. All in all, it was easy to handle because we have a great infrastructure at the Film Academy with a huge render farm.

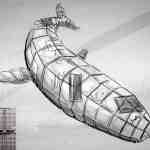

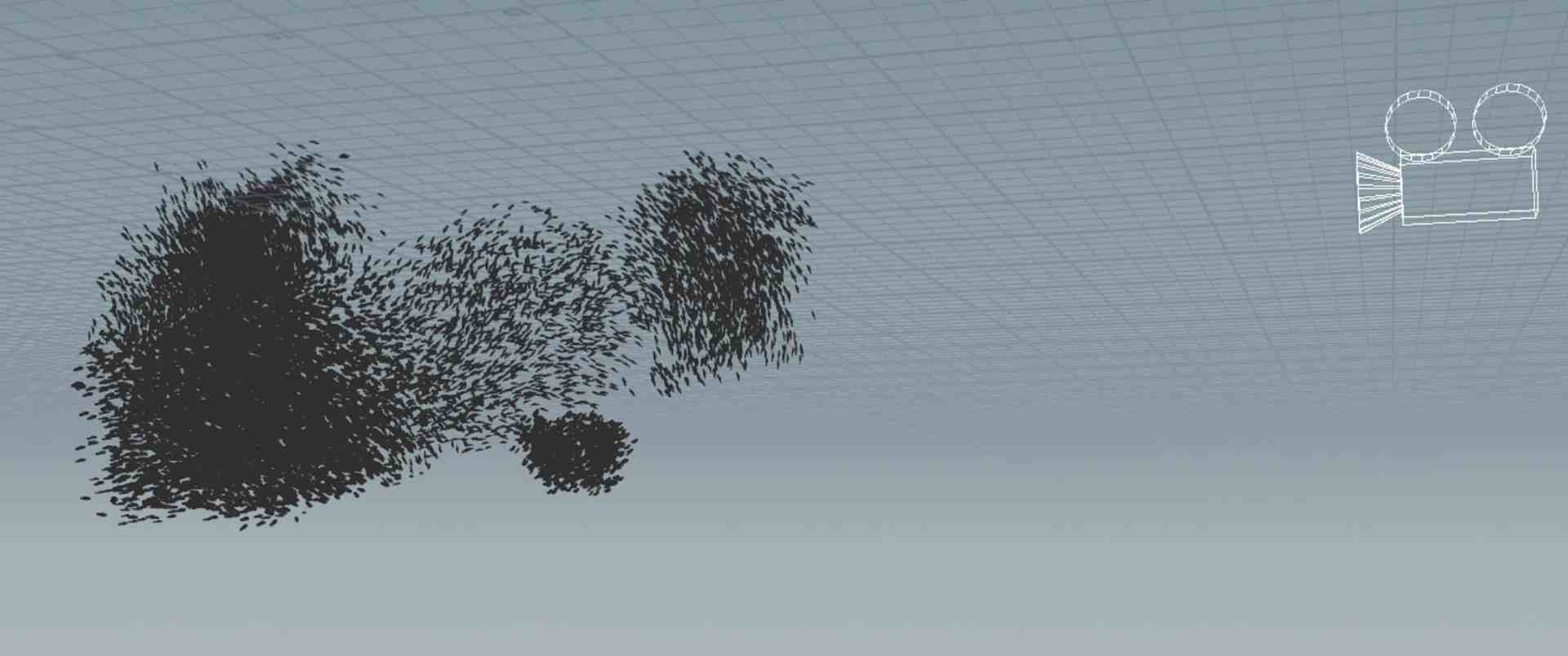

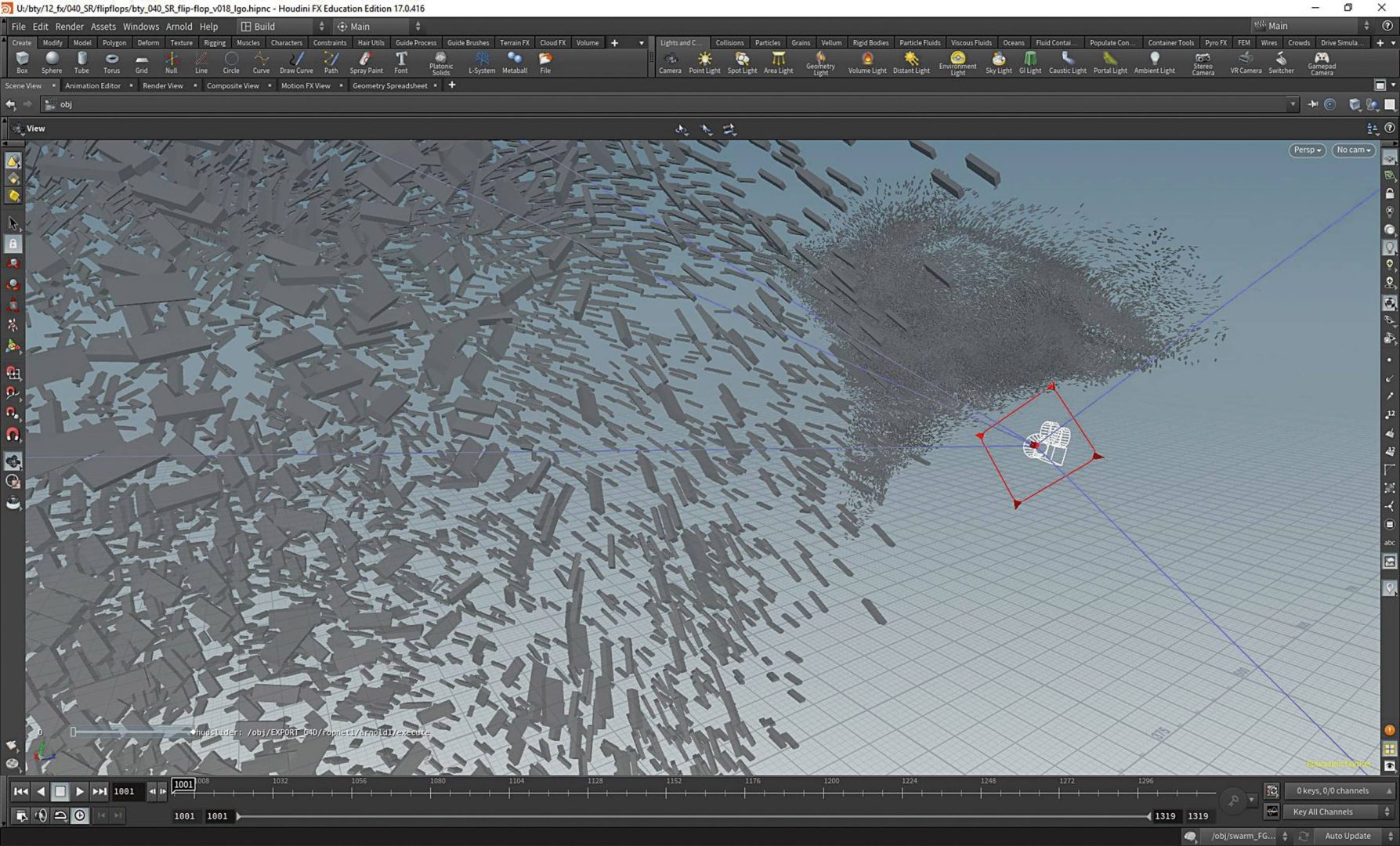

DP: The flip-flop swarm was certainly a simulation marathon with the art direction of “Fish Behaviour”. What was your approach?

Lukas Gotkowski: The flip-flop swarms were created in Houdini. We created point clouds in 3D space and used vector fields to move and align them. These fields were generated in such a way that they depict the movement patterns of a school of fish. The movement of the particles could be customised with additional parameters to change the speed or size of the individual small shoals. In this way, we were able to manipulate the movements not only realistically, but also with artistic control. After creating the simulation, several models of the flip-flops were attached to the particles to transfer the position and orientation of the particles. In addition, further variables that were helpful for shading – e.g. size and colouring – were distributed to the points. The data was output using the Arnold exporter (*.ass files) so that it could be prepared as flexibly as possible for Arnold in any software package.

DP: As water is always complex, how was the exposure – especially the sunlight that “illuminates” parts of the flip-flop swarm – achieved?

Pascal Schelbli: We filmed the pool water from the hotel where we were staying during our shoot and used it as a gobo. As I said, “The power of the filmed material”.

Marc Angele: We used the same light rig in the flip-flop scenes as in the other scenes. Here, however, it was very important to turn up the environmental fog a little. This is the only way to create a certain depth in the room and make the swarm look big and powerful. As a side effect, this also created more god rays in the volume, which resulted in beautiful variations due to the movement of the swarm.

DP: The animation of the underwater creatures is the centrepiece of the look: what were the differences in approach for you in order to achieve the necessary realism?

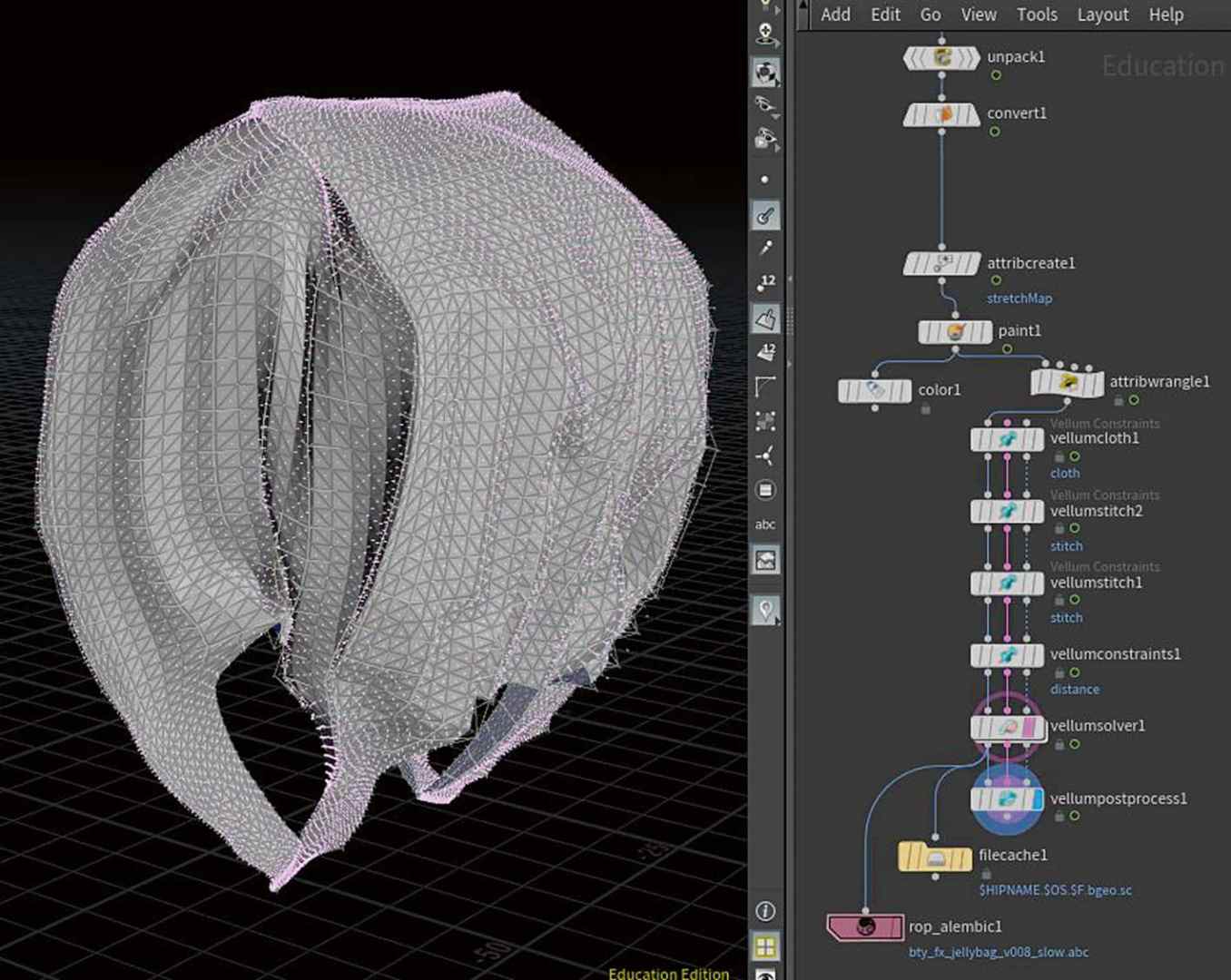

Pascal Schelbli: I think I’m speaking on behalf of both of them here, but I think what saved our butts was that we shot an underwater reference of all the materials. I also think that the turned backplates also contribute to the realism. Keyword bags: The challenge was that the geo moves “crumpled” to the animation and that could be solved a little more elegantly nowadays. We used Vellum to create a cloth simulation and generated the crumpling through displacement.

Marc Angele: Yes, I can only emphasise what Pascal says. The references were simply worth a lot! Personally, it was also extremely helpful for me to dive myself and see the underwater world with my own eyes.

I hadn’t realised before how many particles were floating around in the water and how short visibility is – keyword: environmental fog. Or just observing all the Fresnel effects underwater was very helpful for later understanding. Of course, we used the internet and the BBC series “Blue Planet” to help us visualise the movements of the individual animals. So to summarise: references, references and references.

DP: If we look at the entire pipeline: Looking back, where could you have worked “easier” or changed the order?

Pascal Schelbli: We didn’t have a pipeline. (Laughs) But now I almost only work with one and, looking back, we could probably have been a lot more efficient. Marc has become a pipeline pro in the meantime and thanks to him we always had our server in order. But he can definitely say more about that.

Marc Angele: Haha, yes, it wasn’t quite as bad as Pascal says. We already had a small pipeline that loaded all the tools correctly and made sure that the render farm didn’t do any rubbish. But of course, today we would automate a lot more and use production management tools to get a better overview of the whole project. Maybe then we would have finished a bit more efficiently and faster. But The Beauty only had 15 shots, so it was doable without a big pipeline.

DP: And if we look at the experiences from “The Beauty”, what tricks and experiences do you still use today?

Pascal Schelbli: From a director’s point of view, definitely the preparation! Yes, this is sometimes difficult in the industry as a freelancer for reasons of time and money, but a detailed animatic with elaborate designs and precise references is much more effective than, for example, describing the film/product in words.

I still find the combination of documentary material and VFX a very exciting form of storytelling, as you manipulate an obviously unadulterated image with 3D elements. Quasi deep fake in a creative way.

Marc Angele: With this project, we were able to take a lot of time to take a closer look at something, learn new technical approaches or simply push an iteration further. I still benefit today from the knowledge I acquired during that time.

Because we had enough time, we were also able to organise two reshoots, which really improved the quality of the shots. Unfortunately, there’s rarely time for such things in everyday working life, so I wish I had more time for quality in almost every project.

DP: Where would you take the theme if you were to make “The Beauty 2”?

Pascal Schelbli: Sustainability was and still is very important to me and I also have a new film about sustainability in the post.

The idea of combining two things is nothing new per se, but if I were to choose a similar theme again that could work under the same guise, it would be groundwater pollution from pesticides and microplastics: frogspawn with polystyrene beads or algae made from nylon threads perhaps.

DP: How long did you work on the film and how big was your team?

Pascal Schelbli: It took us 20 months from the first sketch to the finished film. When the idea and the “story” came up, we had a great team of friends who joined the crew: David Dincer, who studied image design, specialised in the course of his studies to become an excellent underwater cameraman. It was then clear that we would actually shoot it and not do FullCG. Marc Angele supported the project right from the start and brought excellent shading, lighting and compositing skills to the table. They were joined by Noel Winzen, an animation and rigging genius like no other, Lukas Gotkowski, the Houdini magician, Fynn “ZBrush” Große-Bley, Aleksandra Todorovic and Tina Vest, who produced this elaborate project, and of course Alexander Wolf David and Robin Harff, who also gave us goosebumps on the audio level.

TEAM

Director & Concept: Pascal Schelbli

VFX Supervisor: Marc Angele

Producer: Tina Vest, Aleksandra Todorovic

Creature TD: Noel Winzen

TD: Lokas Gotkowski

Underwater Cinematography:

David Iskender Dinçer

CG Artists: Pascal Schelbli, Marc Angele,

Noel Winzen, Fynn Große-Bley,

Lukas Gotkowski

Editing: Pascal Schelbli

Grading: fatrat Colour Grading

Voice Over: Charlie Gardner

Film music: Alexander Wolf David,

Petteri Sainio, Meike Katrin Stein

Sound Design & Mixing: Robin Harff

Production company: Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg GmbH

filmakademie.de

is.gd/filmaka_beauty

DP: Where has the team ended up in the meantime?

Pascal Schelbli: I’ve moved back to Switzerland and work here as a freelance director and 3D artist. I’m part of a collective called PULK, which consists of similar creatives. Marc and I have already done a few advertising jobs together and, as already mentioned, are working on a new film together.

Marc Angele: I now live in Berlin and Zurich and am also self-employed. Sometimes I work directly for clients and agencies on my infrastructure, but I also often freelance for a few big London VFX houses. Most of The Beauty team are now freelancers, which I’m personally really happy about as it means we’re always working together.

After training as a graphic designer, he developed into a motion designer/CG artist. He directed various corporate films and broadcast openers and then began his studies at the film academy, which he completed with “The Beauty”. Today he works as a freelance director and CG artist in Zurich. pascalschelbli.ch

Marc is a CG and VFX supervisor in Berlin and Zurich. He studied Animation & VFX at the Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg and graduated with the film “The Beauty”. He also loves working on set and has experience on over 60 different sets. marcangele.ch