Table of Contents Show

My first contact with a Quantel Henry was during my training as a media designer for image and sound at Voss TV Ateliers in Düsseldorf at the end of the nineties. In addition to three Avids, a Discreet Logik Inferno and two tape-based editing systems, there was one of these wickedly expensive effects systems from England. Of course, each of these systems was housed in its own suites designed for customer visits and the more expensive the respective suite was, the less likely it was that a young, pimply-faced apprentice like yours truly would be allowed anywhere near it. So I could only get an idea of what a Henry was and what you could do with it bit by bit. But as soon as I had formed a reasonably clear picture, I knew that I wanted to work on the Henry.

you had to rethink things accordingly.

Of heavy boxes and rodents

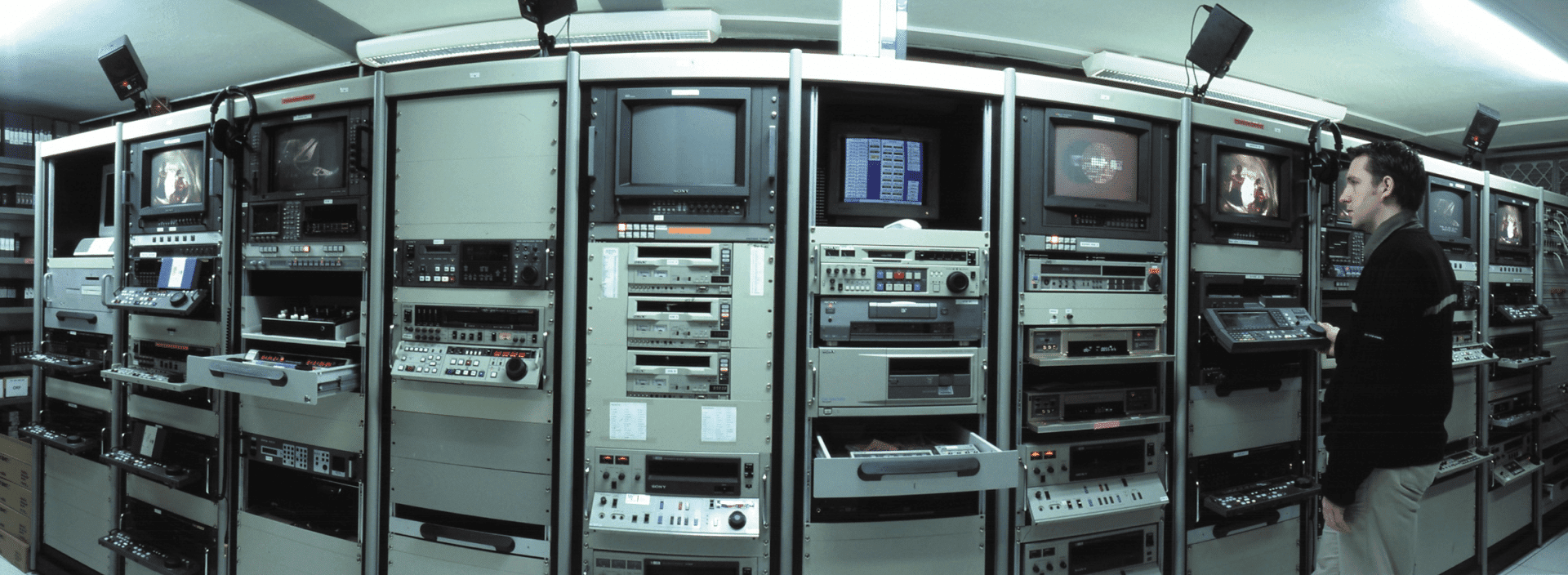

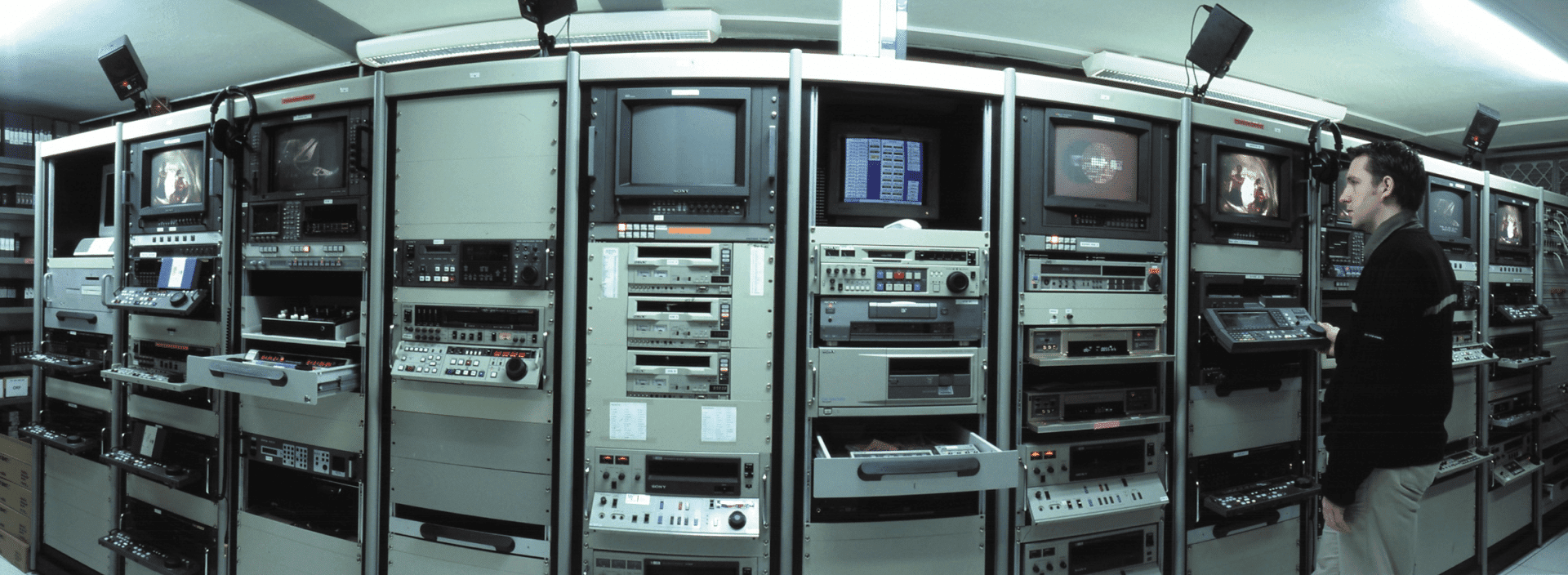

So what was this machine that the young apprentice found so fascinating? The Henry was an online compositing and finishing system from the British company Quantel. The Henry had proprietary hardware designed and produced by Quantel, which was directly addressed by software from the same company. Anyone who thinks Apple’s approach of closely integrating hardware and software is restrictive did not experience Quantel back then. Every major function within the software was assigned to a dedicated board in the mainframe. The whole thing was supplemented by memory.

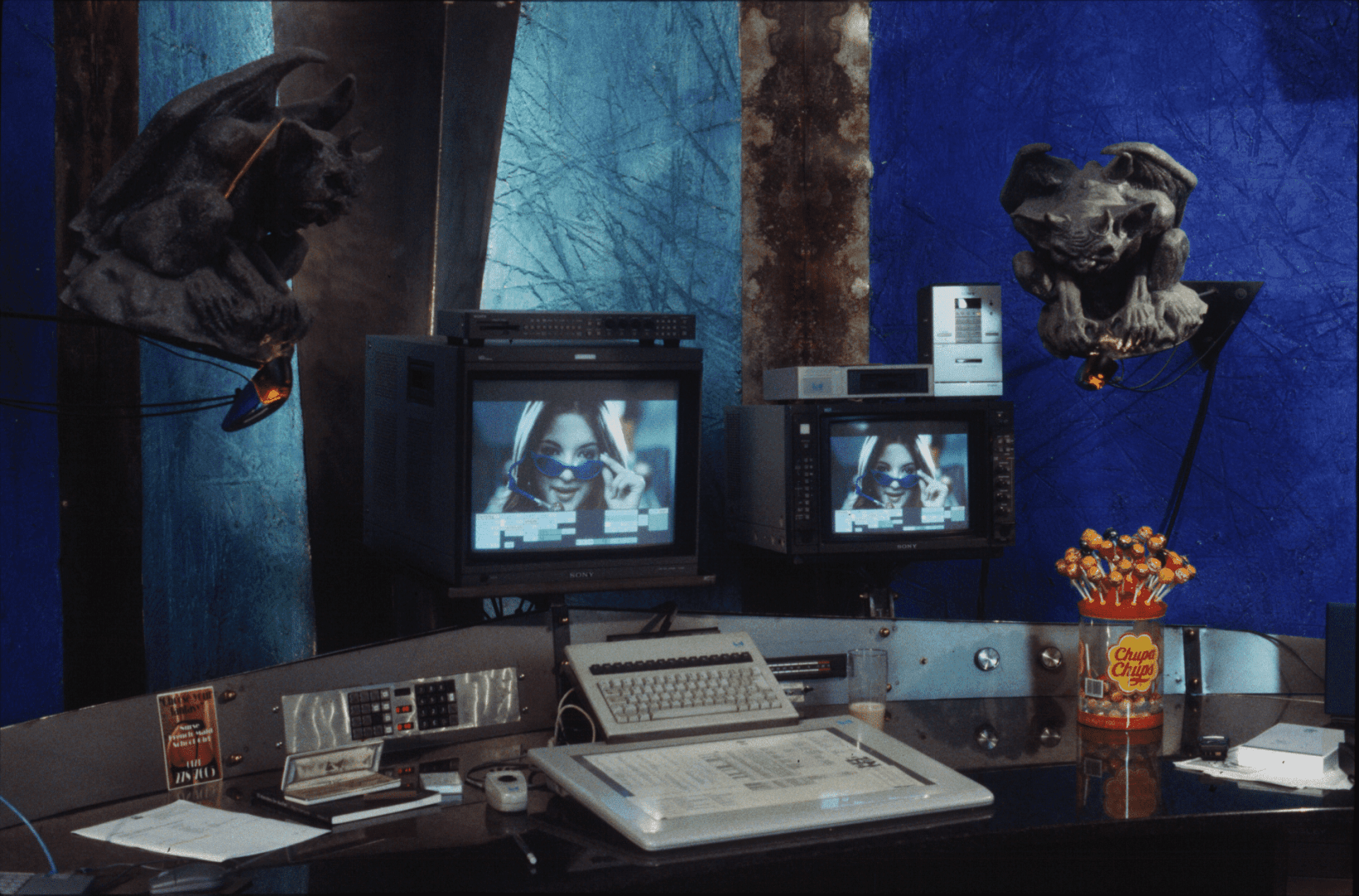

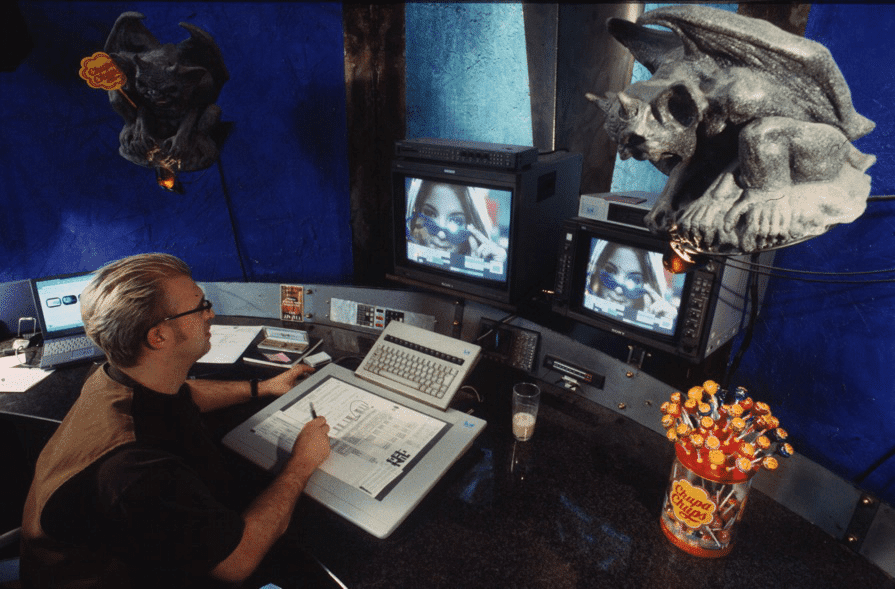

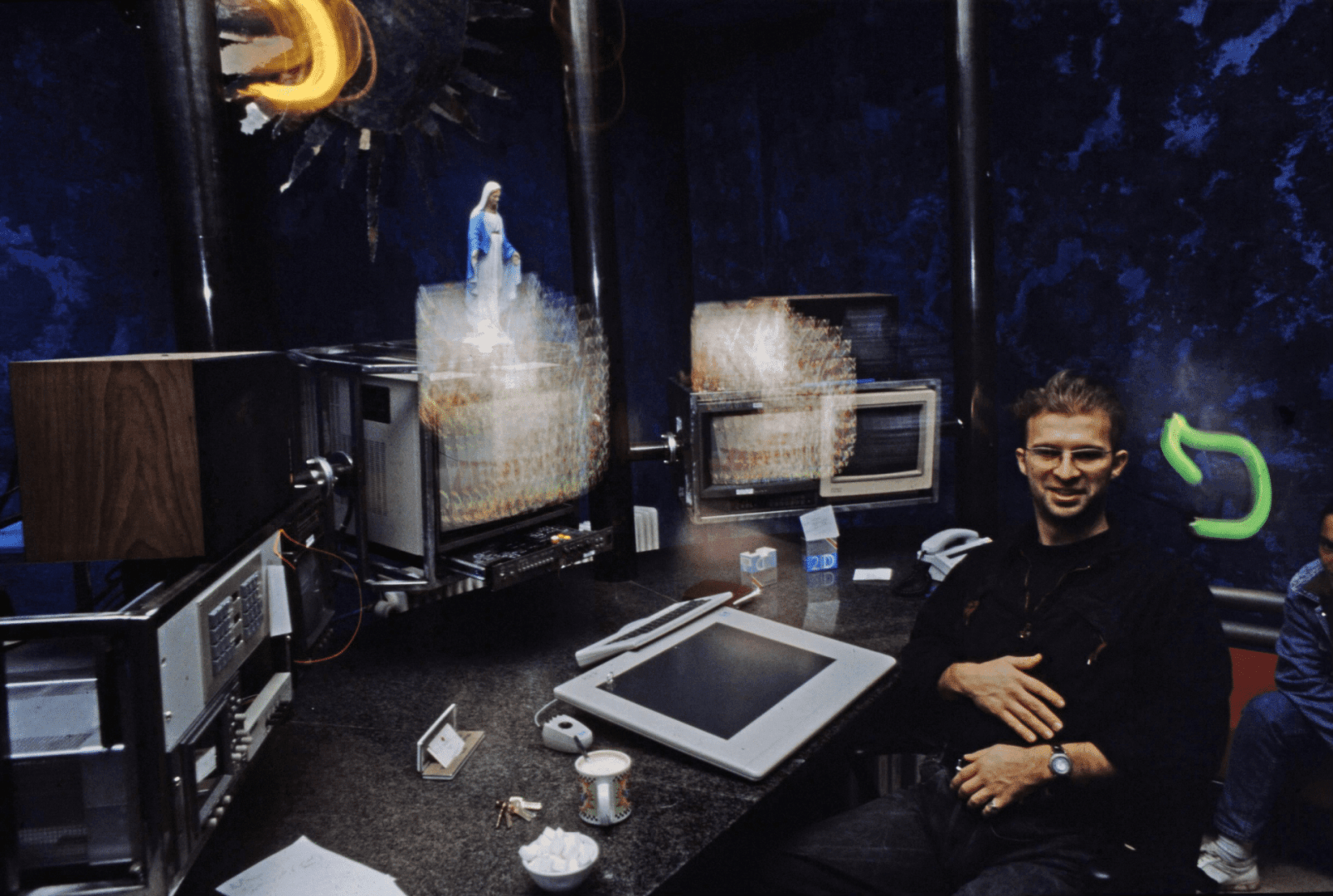

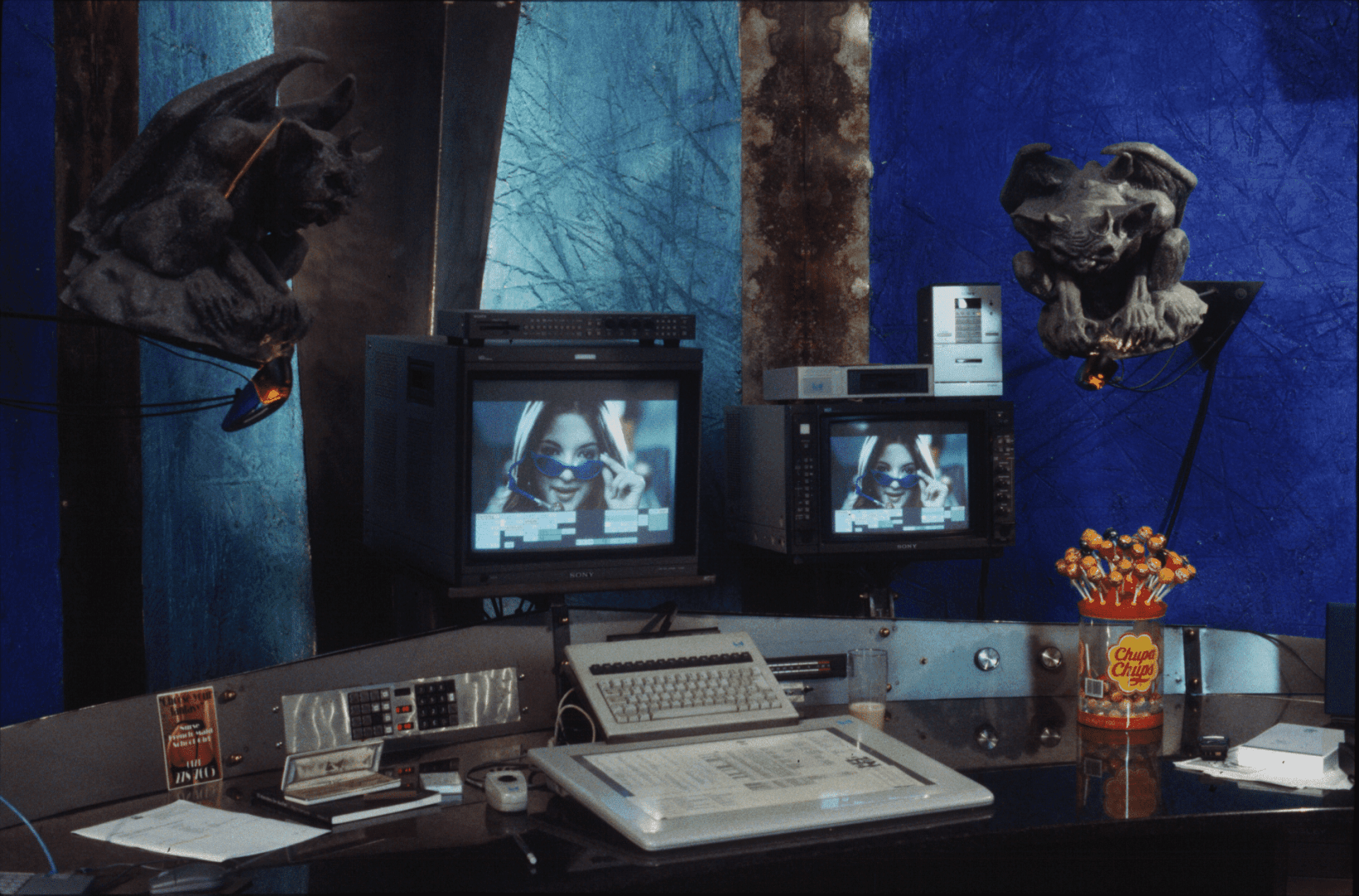

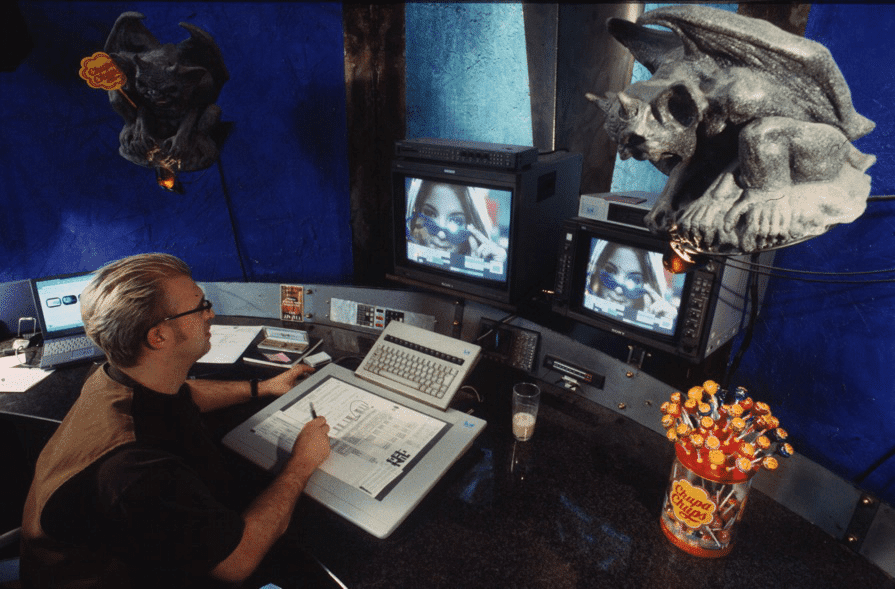

A considerable 30 minutes of memory for the time. In an incredible 720 × 576 pixels. But uncompressed. This memory was then distributed across two so-called Dylans. These were the Henry’s disc arrays and if you wanted to keep your discs in the right place, you’d better carry them in pairs. So, one mainframe, two Dylans and – bang – 24 units were occupied in the rack. Because you didn’t put a Henry under or on the table, but of course he sat in the cooled technical room. The artist was then given a keyboard in his suite, a – let’s say – generously sized tablet with a pen and a hardware accessory that is really hard to imagine today. A kind of thumbstick that you could hold in your hand, with four buttons arranged above it. Quantel officially called it the Hand Control Unit, everyone else called it a rat. And what did the future Henry Artist view his work on? On a class 1 Sony PAL monitor. The Henry was not familiar with a dual-monitor layout.

In keeping with the Henry’s minimalist design, the broadcast monitor also became a GUI monitor. The user interface could be shown and hidden by swiping to the side with the pen. So it was natural to spend eight, ten or sometimes even fourteen hours in front of these things clocked at fifty hertz. The fact that you went home afterwards with a bit of a headache probably needs no further explanation. What we should mention, however, is the price. As the Henry was available in various expansion stages, was later supplemented by the Editbox at the bottom and the Henry Infinity at the top, and price lists were well-kept trade secrets, it is very difficult to give a clear answer here.

But to give an order of magnitude: You could easily buy your own home with the money you wanted to invest in Quantel equipment. It is said that a fully equipped Henry Infinity could be bought for 1.4 million Deutschmarks in 1998. And Quantel knew how to collect this money: Important customers were flown to Newbury in the company’s own helicopter to convince themselves of the merits of their future Henry.

Welcome to Henry

The price and the proprietary hardware explain why it was so difficult for my younger self to get hold of and learn the Henry in the first place. This machine had to be well booked to amortise the enormous purchase and maintenance costs. Nobody wanted to risk a greenhorn accidentally deleting the current Persil campaign because he needed storage space for his first attempts. To make matters worse, YouTube and the like did not yet exist as a source for tutorials.

So without an experienced artist to take me under his wing, it wasn’t going to work. But with some negotiating skills, I managed to convince the two Henry artists in my training company. Now I was finally allowed to take my first steps on the legendary machine myself. Some time later, I finally got my hands on five training tapes, which I played on my VHS recorder until they were unrecognisable. This is what the granddaddy of online tutorials looked like.

The Henry’s interface was very special. The decision to turn the broadcast monitor into a GUI monitor at the same time required a number of decisions. The lower quarter of the screen was reserved for the menu, the rest consisted of either the content to be edited or the desk. Anyone who thinks of a PC desktop when they hear “desk” is unfortunately only partly right. This is because Henry used a completely different analogy to visualise the handling of data than pretty much every other software manufacturer.

While the classic PC is based on the analogy of a desk with folders and files stored in it, Henry used the analogy of a cutting table, which was widely used at the time. This desktop had three reels, i.e. film racks, on which clips could be stored. This was quite logical, as most of the artists who were to work with Henry came from the analogue film world and had had little or no contact with classic PCs. Henry was released in 1992, when digitalisation was still really new territory.

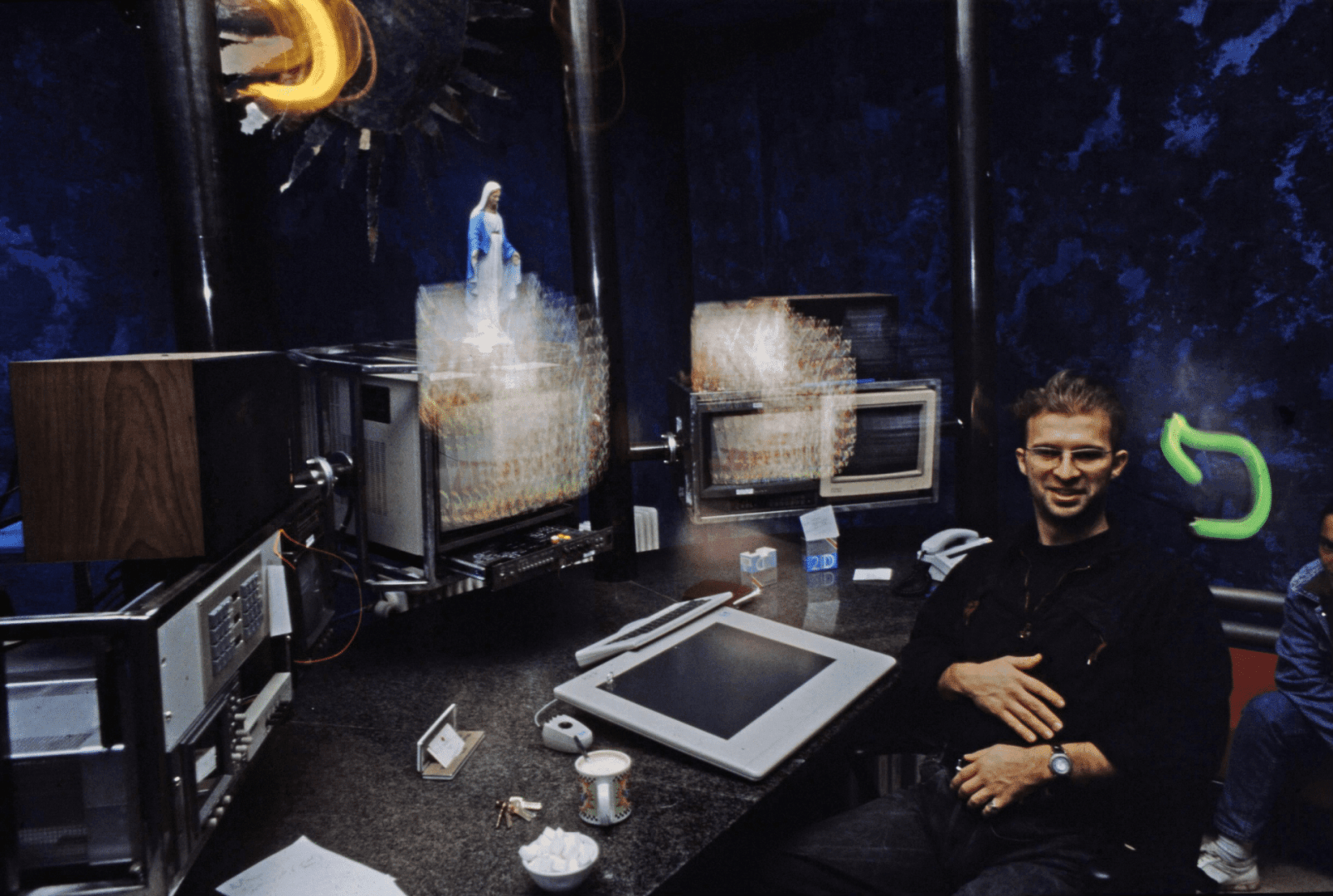

Clips could be sorted and edited in the centre and right-hand reels, while so-called packs could be created in the left-hand reel. Packs were several clips that could be layered on top of each other and then taken into the “Blender”, the compositing area of the Henry. And there you had transforms, blur, colour correction and keying at your disposal. That was it. No 3D environment. No node tree. Plug-ins? When I asked about plug-ins, a very self-confident Quantel employee simply said: “Mr Zapletal, a good artist doesn’t need plug-ins”. Fortunately, Quantel had integrated its then already famous Paintbox into the system and tracking took place in a module called “ALF” – Auto Lock Follow. The marketing team had once again gone all out for the christening.

At that time, the number of layers I could take into the Blender was limited to six. You can’t really imagine it today, but that was enough for a lot of comp tasks back then or you just worked in several steps. Nevertheless, I was absolutely thrilled when “my” Henry got an update. Suddenly I had a Henry V8 under my fingers, so eight layers in Blender.

But there were also two other features: Firstly, I now had a small audio mixer with eight motorised controls next to my tablet, which then moved according to the set level when the clip was played. This was pretty pointless when editing commercials, but it was a party trick favoured by many customers.

Secondly, clip history. The setup no longer had to be saved separately in the library, but was virtually “attached” to the clip. A rendered clip could now simply be inserted into an edit, cut, blended or used in any other way and then removed and edited again at any later point in time. This was an incredible time-saver and made my work on the Henry much faster.

Speed is everything.

And that brings us to the Henry’s real strength: speed. Because this resulted not only from the incredibly fast proprietary hardware at the time, but above all from a very well thought-out user interface. The menus were organised in a strict hierarchy from left to right, with no windows or nested menus. All in all, the Henry had an estimated three hundred different buttons. That’s what you call focussing on the essentials. The consistent use of the tablet was another reason for this speed. If you had the rat in one hand and the pen in the other, you could work incredibly quickly. The thumbstick and the four buttons were context-sensitive, so you didn’t need any shortcuts in Henry. The keyboard was only needed in the library for saving and searching. And the use of the pen was also miles ahead of its time. Swiping outside the tablet area was the way to switch between full-screen view and menu view or to retrieve a clip that had been thrown away. Because in the Henry there was neither a rubbish bin nor an undo function. A clip that was no longer needed was placed on the “CRF” – the cutting room floor. The analogy to the cutting table was also consistently applied here. And if you did need it, you simply swiped the pen outside the desktop – and it was back on the pen.

However, the functionality that I still miss today with my Wacom is the “dropping” of a clip. If you had a clip on the pen, for example to take it to another module such as the Paintbox, and you changed your mind, you simply lifted the pen a little further up from the tablet and the clip was put back in its original place – i.e. dropped.

And there was another area where Henry consistently lived out the speed – in editing. Just as there was no node tree, there was also no timeline. Clips were cut together on the desktop in the centre and right reel. This could either be done with “unfolded” clips, where you could see every single frame (realistically a maximum of four frames, more did not fit into the PAL resolution) or with “folded” clips, where every single cut image could be seen as a thumbnail. If you had attached two clips to each other, you could move the cut by dragging the pen up or down between the two clips using a yellow handle. quantel called this technique “gestural editing”. Operations such as fades or wipes (it was the nineties after all) were carried out directly in the Full Screen Viewer or via the menu on the desktop.

If you came from AVID, it was all very confusing, but once you got the hang of it and had a good logic of how to organise your rushes, your edit and your comps on the three reels, you could cut incredibly quickly. But where there was no timeline, there was also no multi-layer timeline. And so with graphics such as corner logos, URLs and the like, you were spoilt for choice – either you rendered the corresponding logo separately on each individual edit, which could get really out of hand, especially with cut speed ramps, or you committed all your edits and then overlaid the graphics completely. In this case, it was necessary to save everything properly in the library so that you could still see what had happened when afterwards.

Who needs folders..

The library – this was probably the slowest and toughest part of the Henry. While all the other components had their dedicated boards with incredibly fast processors, the library was managed by a 20 megahertz Motorola CPU. So just listing the entire library could give you time for a coffee break. More problematic was that the library had no folder structure or even the concept of a folder. You could either scroll through the library and manually search for the clip you wanted or use the search function – which again called the terribly slow Motorola CPU into action. If you consider that originally each pack, which was basically the setup for a comp, had to be stored separately without a folder, it becomes clear how important a proper naming convention was here. Unfortunately, among my colleagues at the time, the longer the session and the more nonsensical the customer feedback became, the more and more swear words crept into the names. I won’t reproduce them here for obvious reasons; no-one back then would speak to their mum in the way they called these set-ups. In the end, we knew that the wilder the name, the closer it was to the final version.

Clip History was perhaps not intended to help with the beauty of the language, but with the management of the many setups. Because – at least that’s the theory – if every clip that is blended in a timeline carries its setup with it, you would only have to save one timeline and thus have everything saved. And this worked well in many scenarios. But as soon as speed ramps, sandwich fades or the aforementioned graphics over several cuts came into play, it became difficult and you had to save individual steps again and the library grew again.

Under the bonnet, however, the library was really ahead of its time. I still remember two features very well: firstly, Frame Magic. The name sounds pompous, but in the end it simply meant that every frame in the library was well referenced, thus preventing frames from being loaded twice unnecessarily. With thirty minutes of PAL memory, this was a highly desirable feature. When copying clips, new media was never created, only referenced. When conforming or loading archives, Henry always checked whether this media was already in the system. This was a surprisingly good way to manage the limited memory.

Whoever writes archives, stay alive ..

Speaking of archives. Just like ingest and playout, these were tape-based. So not LTO or a similar data format, but based on D1 and later Digital Betacam. The media was written to the video tape and all meta and audio data to an MO – a magneto-optical disc with an incredible 640 MB of memory. Once a job was finished, the MO was placed in the Henry drive, a tape machine was connected and every single clip, including any handles in the timeline, was played onto the tape.

If there were comps with clip history in the timeline, the source clips used were also played. If the same job then had to be reloaded, all of this was loaded again. However, since Frame Magic also applied here, meaning that in case of doubt only things were archived that had not already been archived on this tape before, at some point Henry began to rewind and rewind the tape wildly, loading two minutes here, then shuttling to the other end of the tape to load another ten frames from here, and then back to the beginning again. Watching this dance was always a bit fascinating, because even after years of using the device, you could never quite believe that all this actually worked so smoothly and that you had actually loaded your entire project back cleanly at the end. Incidentally, there was no file-based archive solution – with 10 MBit, the Henry’s optional TCP/IP module was only suitable for exchanging stills, fonts and EDLs.

Incidentally, this tape-based archive feature was one of the reasons why Quantel was so popular with the Henry in advertising. It was extremely robust and customers had the security of knowing that they could still access all the data cleanly a year after completion, cut a twenty-second cutdown from the thirty-second, remove the new jammer and insert the next flavour. And if in doubt, you could quickly request tapes and take them to another vendor.

The Infinity Saga

In the meantime, I had completed my training and got a job as a “Junior Henry Artist” at “Das Werk” in Frankfurt. My jaw dropped at the interview when I was shown four Henry suites. Here I was also given my first Quantel pen, including a satin-lined box. This pen was even more important to me than the fancy new title of my first permanent position. For me, it was a kind of accolade: if you had your own pen, you were in the club. At least that’s how it felt back then. Speaking of the club: with four Henrys, there were of course a lot of artists from whom I could learn a lot. One of them, however, was very enthusiastic about performing the aforementioned swiping and swivelling movements on the tablet, so I was afraid more than once that I might pop his pen out of my eye next.

Incidentally, my new colleagues had a nice little trick for learning from each other. When they didn’t have customers, they simply patched the output of another Henry onto their own control monitor. This meant that they could keep an eye on what the colleague next door was up to with one eye – provided it survived the pen attack – and learn a thing or two. This was so easy, of course, as the Henry’s GUI landed directly on a video-out. So you only had to patch a normal video signal.

Most of the time, however, this was not possible because customers were present. Because with all this speed, Henry was designed to be used in customer sessions. It’s hard to imagine in the post-Covid era, but it was quite normal for customers to attend almost the entire production on site. Understandable, after all, they paid around 1,500 Deutschmarks for their Henry session – per hour. For this, not only should there be sushi on the table at lunchtime and the customer’s sofa be nice and comfortable, but the artist should also have a chat, listen to the briefing and, incidentally, finish the film. In this respect, the typical Henry Artist at this time was just as much an artist as an entertainer, sometimes also a shrink or hairdresser. Filigree tinkering was done on Flame and Inferno, later perhaps also on Shake, the Henry was stretched. It sounds like marketing speak, but the superior speed and fast user interface at the time – in addition to the extremely reliable archive solution – made Henry very popular. Conventional PCs of the time simply couldn’t keep up with the rendering power of a Henry.

But what kind of jobs were done at the Henry? Large cinema projects were not his profession, if only because of the SD resolution. However, Henry was at home in advertising. From classic adaptations and look development to complex new productions. The minimalist interface allowed the artists to always react very quickly to the wishes of the clients present. And so the rapid swishing on the oversized tablet sometimes had a bit of a shell game about it. You could quickly create a lot of effect for the customer with just a few movements – the rendering speed did the rest to give the customer the – quite justified – impression that they were getting a lot for their money. In addition to advertising, we produced an incredible number of music videos, trailers, station IDs, image films and the like.

What was also new for me at the plant: the four Henrys at the Frankfurt plant were in the highest expansion stage, “Henry Infinity”. Infinity stood for an infinite number of layers. However, I soon realised that it was not possible to simply add a ninth and tenth layer to the eight layers that I had previously known as the maximum from Herny – the entire architecture and the UI design did not allow more than eight layers to be managed simultaneously. This is why Quantel introduced so-called super layers. If you wanted to integrate even more layers into a comp, you could, for example, “push” layers three, four and five into a super layer. The three layers then became a new one, the content of which could then be accessed within the blender by double-clicking on the layer icon. However, these super layers had to be calculated separately by Henry. In the end, superlayers were a glorified prerender.

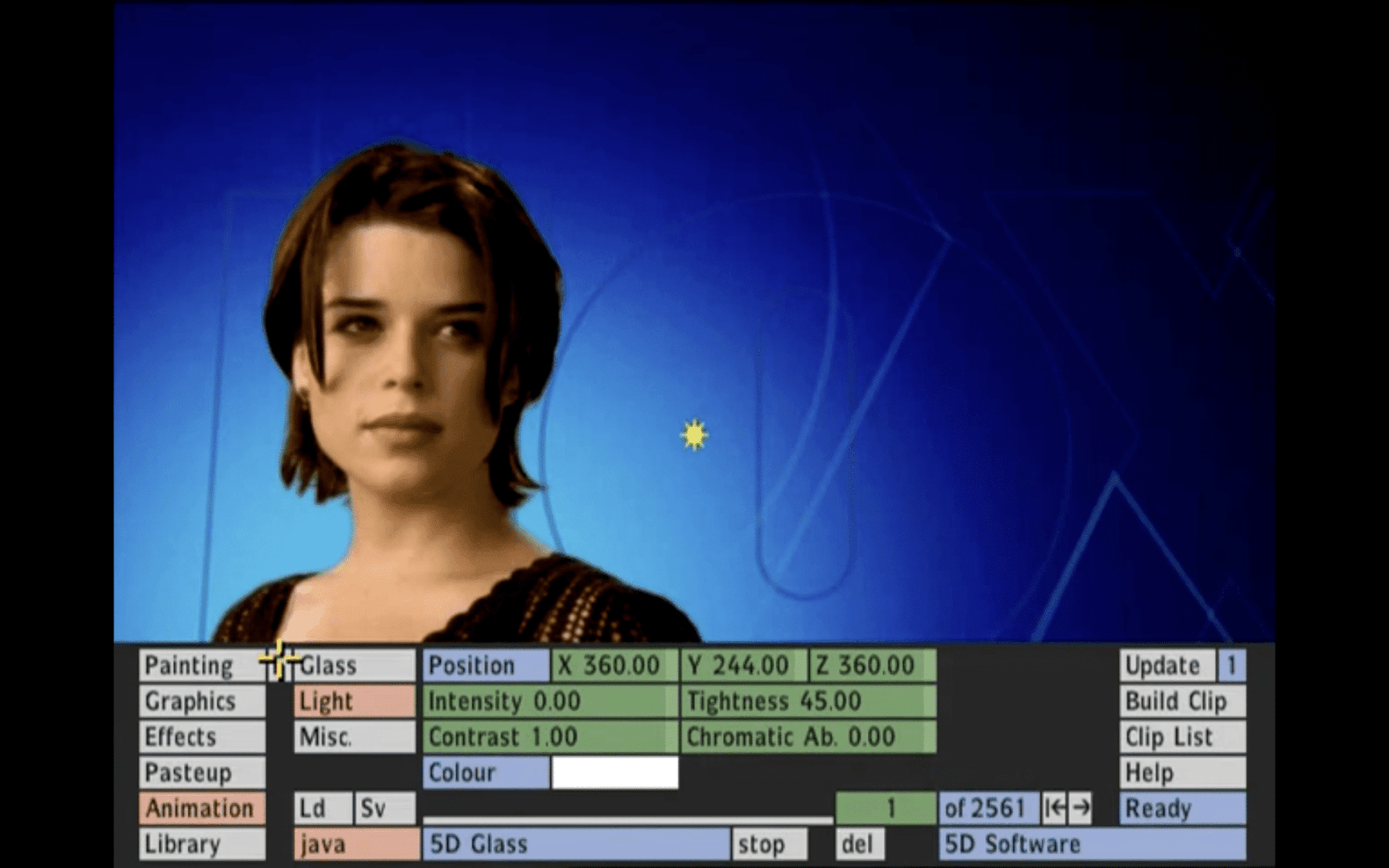

The Henry tries his hand as a team player

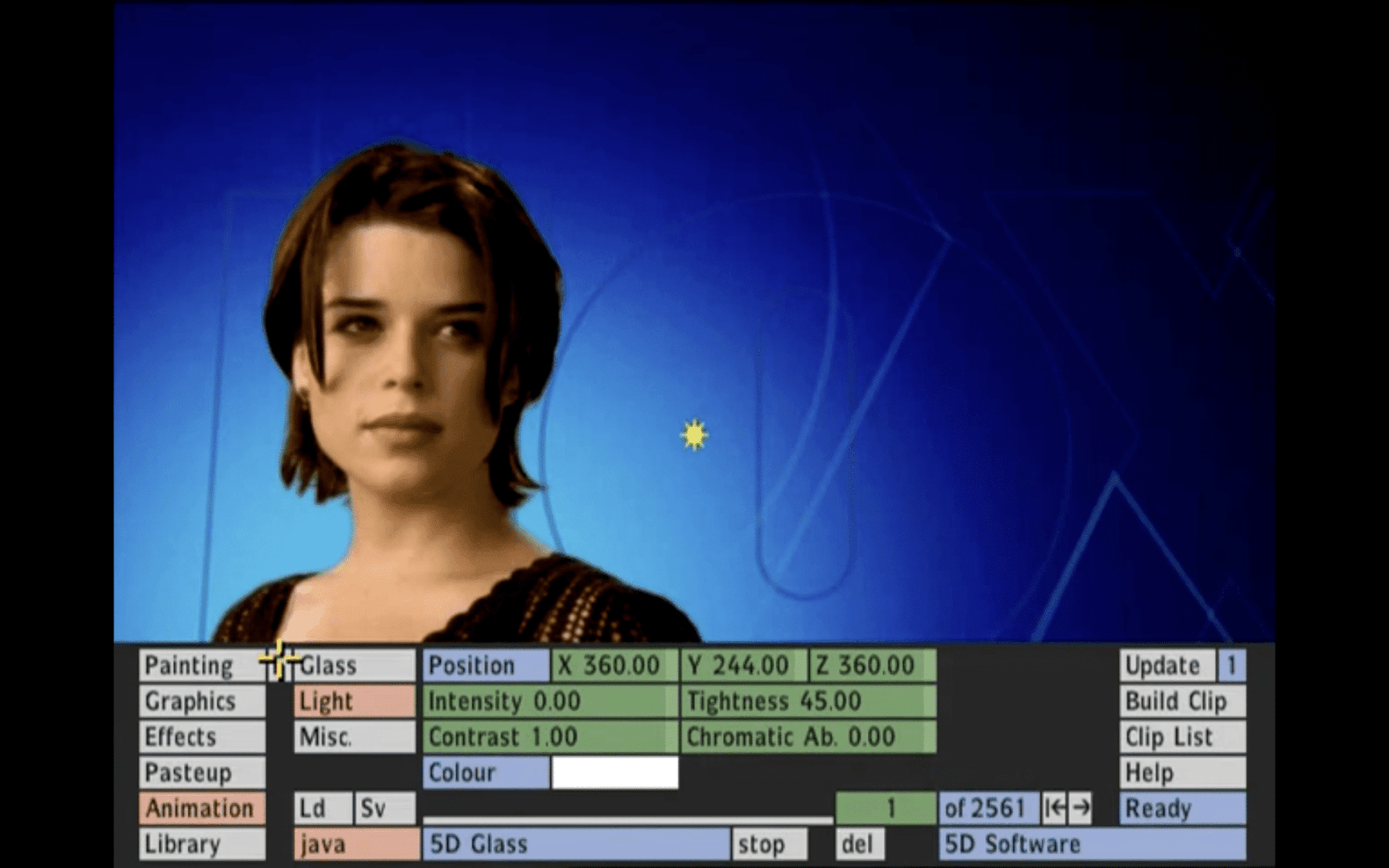

Quantel’s strategy of relying on proprietary hardware was slowly reaching its limits in other areas too. At the beginning of the 2000s, the pressure to open up the system grew. The plug-in manufacturer at the time, 5D, introduced the “Masher”. The Masher was a PC connected to the Henry via TCP-IP, on which 5D plug-ins could then be executed. The parameters could be set via the Quantel GUI. However, as everything had to be sent to the masher for updating via an extremely slow connection, the entire speed and interactivity of the Henry was reduced to absurdity.

Another approach was “Java on Quantel”, which used the aforementioned scripting language to introduce functions that were not possible by default. In its last major update, the Henry finally got something like a keyframe graph, a long-cherished wish of the Quantel community. Unfortunately, the same problem arose again: Java was never known for its speed and the diversions via a third-party interface created such a bottle neck that hardly any artists used the feature. The biggest problem, however, was that the hardware was not resolution-independent. You could choose between PAL and NTSC – but not just like that in the middle of the project: if you had to switch the resolution, all the material was deleted from the Dylans. Oversized files had to be broken up in Photoshop just to be reassembled in Henry. All of this was no longer up to date and the development of the Henry had come to an end.

The echo

With “generationQ”, Quantel launched a new product series that could work independently of resolution and whose proprietary hardware was controlled by a Windows PC. In theory, a “best-of-both-worlds” approach. In practice, the designers of the time unfortunately did not succeed in transferring the strengths of the Henry to the next generation. The user interface lost its speed and the successor eQ was never able to achieve the stability of the Henry. And so the Henry lasted longer than many would have thought. Although the Henry was no longer actively advertised by Quantel from 2002 onwards, in April 2003, when I joined the then newly founded ACHT Frankfurt, there were two brand new Henrys in the rack. The memory had been expanded to an unbelievable one hundred and twenty minutes and had found its way into the case, the rest was well known and should actually serve us well until 2005. However, the Henry became more and more of a conform and mastering tool, the effects were done on contemporary machines like the 5D Cyborg – but that’s a whole other story.

When you talk to artists who worked on the Henry back then, there’s always a bit of nostalgia. The Henry was so fast, the interface so straightforward and the functions not so overloaded. But you mustn’t forget that the Henry could be like that because it was the child of a different era. With only one resolution and just two relevant aspect ratios, without internet formats and without large teams working across several continents. Without workflow tools and shot management. The Henry was designed to allow a single artist to work on a film together with their clients. Long before approvals between two meetings took place on a smartphone. And to be honest, I don’t miss the rat on the table or the booming fifty-hertz monitors. But that swiping on the tablet was cool.

![a group of people in various poses with a focus on a woman in white attire overlayed with the text switchx and the tagline switch anything keep what matters the scene is set against a beach background at dusk digital production A group of people in various poses, with a focus on a woman in white attire, overlayed with the text 'SWITCHX' and the tagline 'SWITCH [ANYTHING]. KEEP WHAT MATTERS.' The scene is set against a beach background at dusk.](https://i0.wp.com/digitalproduction.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/beeble-switchx-hero.png?resize=110%2C110&quality=72&ssl=1)