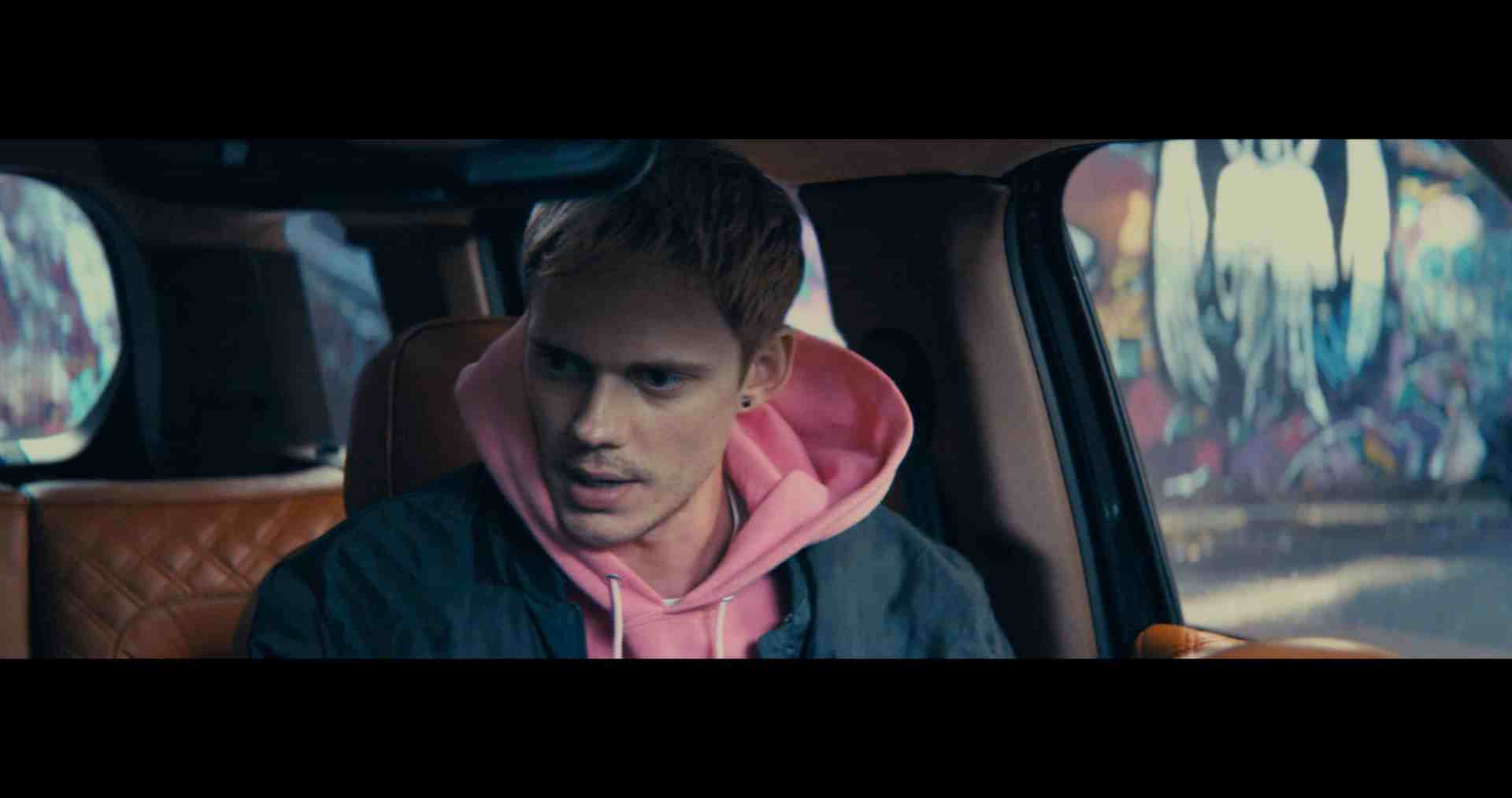

In this behind-the-scenes interview, we speak with Jindrich Cervenka, a seasoned VFX Supervisor at PFX. His recent work on Locked—a claustrophobic thriller set entirely inside a car—offered a unique set of challenges, from invisible compositing to seamless CG integration. In our conversation, he walks us through the creative problem-solving, the surprises, and the collaborative hustle behind the film’s visual effects.

PFX

PFX is one of Central Europe’s most dynamic visual effects and post-production studios, headquartered in Prague with additional offices in Bratislava, Berlin and Warsaw. Known for their versatility across genres and formats, PFX has contributed VFX to major international films, including Land of Bad and Medieval. With a team of over 400 professionals and a focus on both creativity and technical innovation, the studio brings a full-service approach to everything from CG environments and digital doubles to compositing and pipeline development. Locked was a standout project for PFX—not only for its technical demands, but also for the way it tested and strengthened collaboration across newly integrated teams.

Film Introduction – Locked

Locked, directed by David Yarovesky, is a high-concept thriller that unfolds entirely within the confined space of a car. Tightly plotted and visually ambitious, the film turns its single setting into a tension-filled universe, demanding precision in every frame. With no real driving scenes and a heavy reliance on VFX to sell the illusion of movement, lighting shifts, and environmental change, Locked required intricate planning and digital artistry. PFX handled nearly half the film’s shots—about 750 in total—making them a key creative force behind the film’s immersive visual style.

DP: So, how did PFX get involved in Locked? Did the production just slide into your DMs, or was there already a working relationship?

Jindrich Cervenka: We were brought onto the project by Highland, the distribution company, and executive producer Petr Jákl. We’d previously worked together on Land of Bad, so the relationship and trust were already there. This was our first collaboration with director David Yarovesky.

DP: When you first heard “the whole movie happens inside a car,” what was your first thought? “Easy day at the office,” or “we’re going to need a lot of tracking markers”?

Jindrich Cervenka: I didn’t actually hear about it first—I saw it. And my first thought was that this was going to be a pretty chill project. The film was split into six reels, and in the early stages, I saw reels 1 through 4, which didn’t include the end of the film. So it looked like it was mostly going to be about keying behind car windows and a bit of work with digital doubles.

The edit was still open, and I thought that the 3.5-minute shot at the beginning would be cut, shortened, or edited after we talked about the budget. We had a fixed time frame in which we had to deliver, and at first it looked like everything was under control. But then reel 6 arrived, and that long opening shot hadn’t changed. That’s when I realized—it was going to be a real challenge.

Shortly before this project, we joined forces with a new team in Poland, and it was clear from the start that we’d need their support to meet the timeline. We didn’t have much time to sync up, which made things interesting. Sure, we’re all from the same industry, but every company has its own way of working—different structures, different workflows, different pipelines. Getting aligned quickly wasn’t easy, but it pushed us to communicate better and work smarter. Looking back, it was a real learning moment that made us stronger as a group.

The first preparations, of course, were done with David Yarovesky. We had several long video calls where we clarified what was supposed to happen where, and what was more or less important.

DP: Roughly how many shots did you end up doing for Locked, and how big was the team handling the VFX? Was it a distributed setup or mostly in Prague?

Jindrich Cervenka: In total, we worked on around 750 shots, which came out to about 45.75 minutes – roughly half of all the shots in the film. Altogether, 60 artists worked on the film, along with 3 supervisors, 4 team leads, 3 coordinators, and 3 production staff – plus others who handled the operations of the individual branches. Our teams in Prague, Bratislava, and Warsaw worked on it for a total of 4 months.

DP: Were you on set during production? With the car being the entire universe of the film, I imagine VFX needed a seatbelt too.

Jindrich Cervenka: Unfortunately, no. I love being on set, being part of important decisions, and having an influence on things. But I wasn’t present for this particular shoot. However, Robert Habros, who was the on-set VFX supervisor, did a great job.

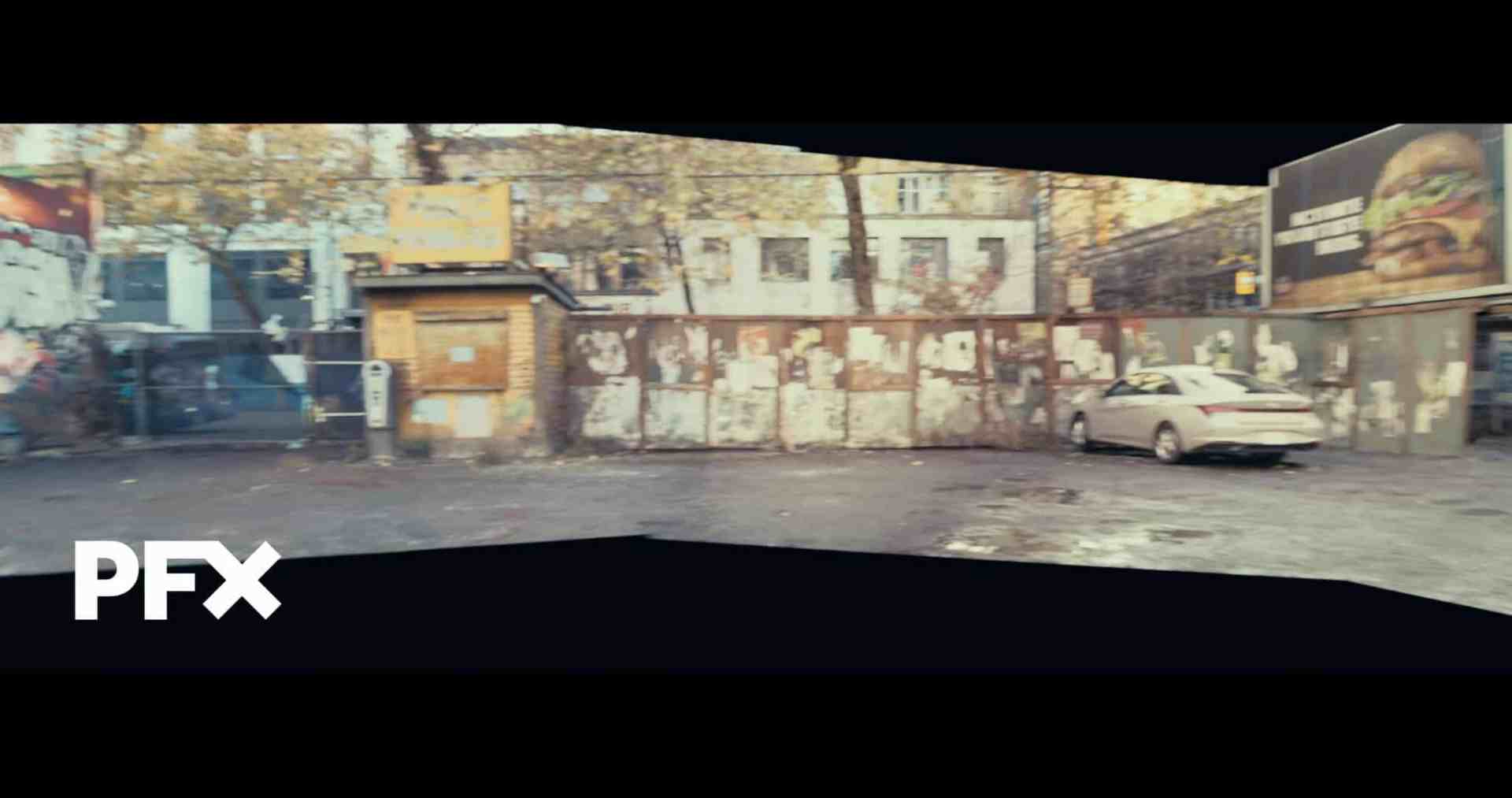

DP: No real driving in the film — so how much of the outside world was green screen, LED, or full CG comp?

Jindrich Cervenka: We received a detailed lidar scan of the parking lot where a large part of the film takes place, along with plates from a total of 8 cameras, which were used as projections on simplified lidar geometry. For the driving scenes, we had 180-degree plates from 6 cameras. We didn’t have to replicate any backgrounds in CG for the interior shots—the footage captured by the shooting crew was completely sufficient for our work. Of course, it wasn’t just about the backgrounds, because our shots were mostly filmed in a studio, where the car set was missing windows. So we had to have a complete CG version of the car, including the interior, which was used in the side mirrors and for reflections in the windows.

DP: When the same tiny set is being shot for weeks, continuity is king. How did you handle that from a VFX point of view — especially lighting and reflections?

Jindrich Cervenka: This wasn’t easy. As long as the car was parked, we just divided things into day and night, and we could reuse setups, which worked well in most cases. But the moment the car started moving and the background changed dynamically, it became quite difficult to set consistent rules for all the compositors so that everything would work together smoothly.

The problem was that there were a lot of lights in the background that the car was supposed to drive through, and then a bunch of random lights shot in the studio—which just didn’t match. The only thing you can really control is which parts of the car react to the background lighting and which to the studio lighting, and how to blend those two so it feels believable. Once the car started moving, it had to be done shot by shot, and there was no way to apply one universal rule. So we handled it case by case, depending on the shot and the editing context. There were a lot of back-and-forth iterations.

DP: Did you pre-vis anything to plan these sequences out, or was it more of a “shoot first, fix in comp” approach?

Jindrich Cervenka: For the bullet time shot, we had a visualization that was used as a guide during the shoot, within the limits of what was possible. Even though it was a bit ambitious, I think the final image turned out pretty well. In the part where Eddie gets out of the car, we had to figure things out ourselves and make it fit into the edit. We did several rounds of postvis with the director to understand exactly what we were building. So apart from the bullet time shot, we had to handle everything on our own.

DP: Let’s talk tech. What was your go-to software stack for this one — modeling, comp, render, the usual? Any surprises?

Jindrich Cervenka: For the Locked project, we didn’t need to come up with any new tools for VFX production. We only had a few assets that we reused. Here I’ll go back to the beginning of our talk and the challenge of this project. One of the key challenges was coordinating with a newly integrated part of our team and aligning quickly with David (the director) on shot context—all within a tight timeframe. We’re used to fast-moving projects, and this one really put our internal app “Crossbow” to the test. It helps us with bidding, asking questions, sharing knowledge, and getting oriented quickly. Locked was a great case where the app proved its value. It even pushed us to improve it further. And today, honestly, I can’t even imagine working without it.

DP: I heard you didn’t use CAD data from the car manufacturer. That’s kind of rare. Why build the digital SUV from scratch?

Jindrich Cervenka: For our CG asset, we used the lidar scan as a base—there was no CAD data available, although I’ll admit I would’ve welcomed it. Still, the lidar gave us enough detail to make sure everything on the car was where it needed to be. We needed a detailed model of the car, including the interior, mostly for the reflections we were adding. In a few shots, especially near the end of the film, we had to replace the car with a CG version because a completely different SUV had originally been filmed. In some cases, we only swapped out parts of the car when we wanted to preserve the real-world physics of the shot.

DP: How did you handle tracking in such a cramped, reflective, and not-so-marker-friendly space? Custom tools? Mocha? Despair?

Jindrich Cervenka: Yes, we use 3D Equalizer and have great people who know how to work with it. There’s nothing more to it for now.

DP: What was your approach to rendering? Offline brute force? GPU rendering? Cloud farm?

Jindrich Cervenka: At PFX, we render on a CPU farm within the VFX department. The render engine we used was V-Ray for Houdini, and our farm gives us enough power that we didn’t need to rely on any external render farm solutions. In this case, we didn’t encounter any bottlenecks worth mentioning.

DP: Any AI-based tools sneak into your pipeline?

Jindrich Cervenka: Yes, definitely. We’re working on implementing AI as a tool for artists—to help them do less manual work. As you mentioned, for example roto, and also DMP or cleanup tasks. We also use it for concept work, and sometimes I use it when giving feedback. It’s a great brainstorming tool that, in some cases, helps me quickly and clearly show where we want to go. We’re integrating it more and more into our process, but definitely not in a way where we’re trying to replace artists.

DP: What was the single most difficult shot in the film to pull off, and what made it a pain?

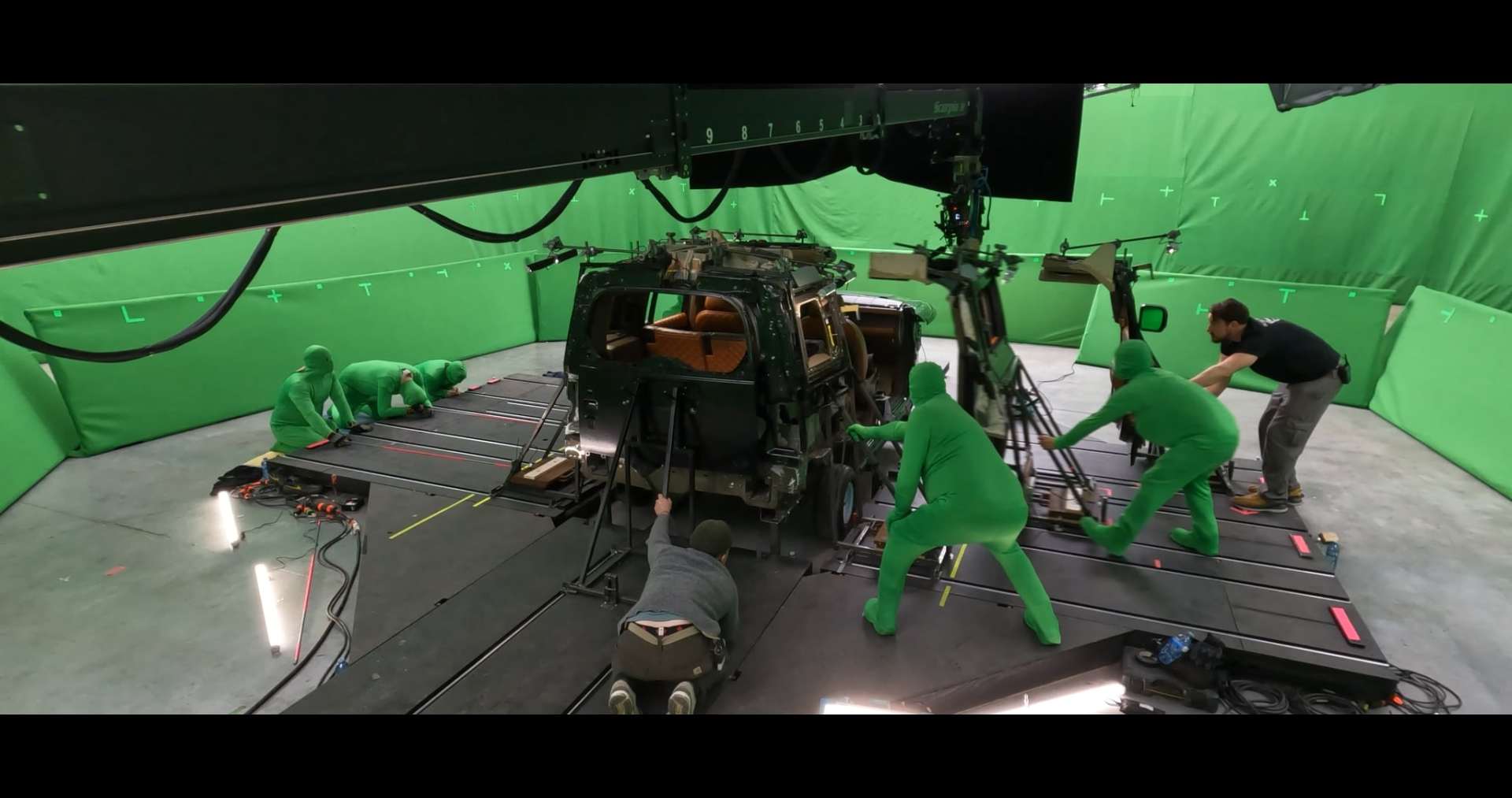

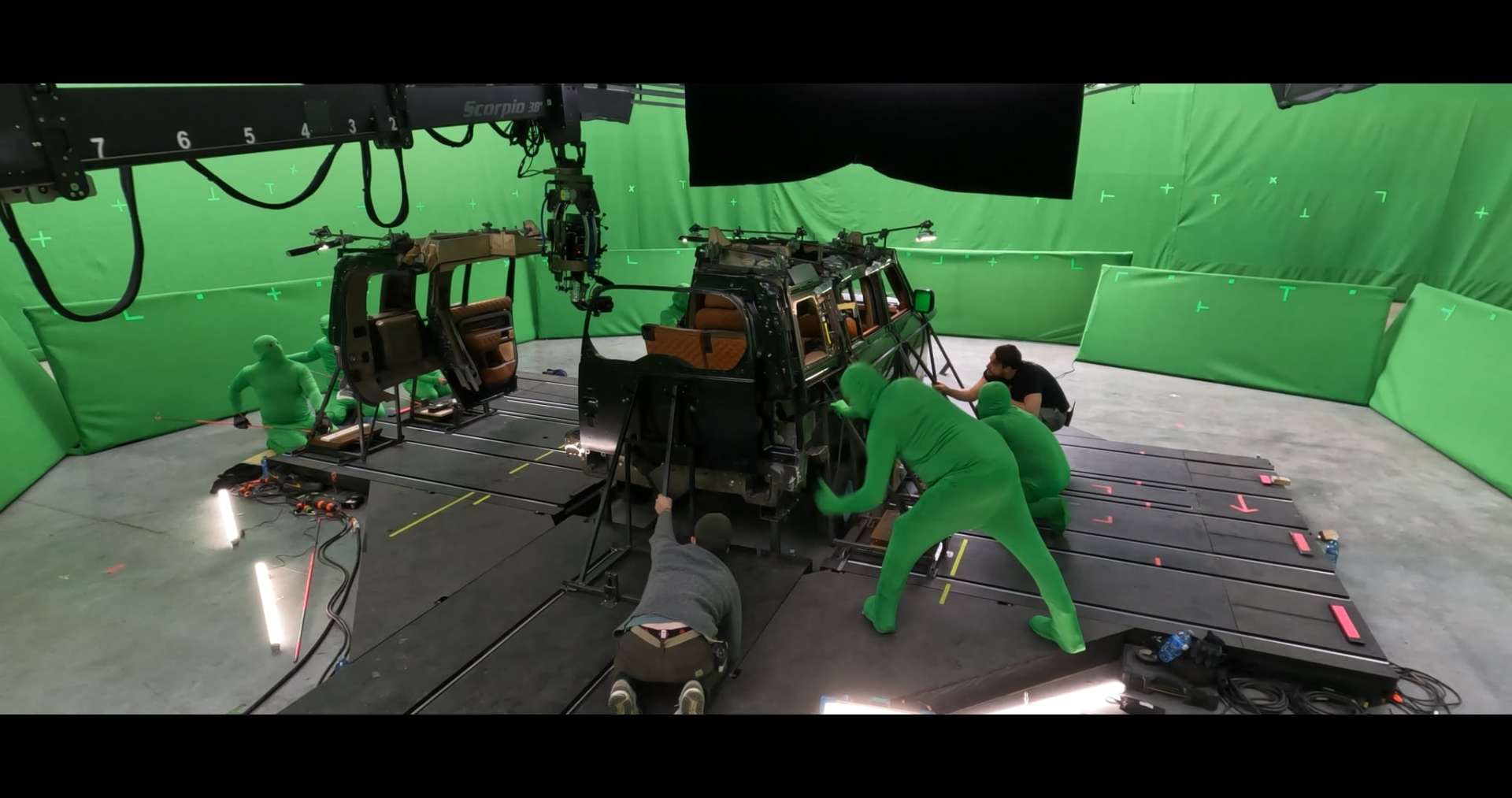

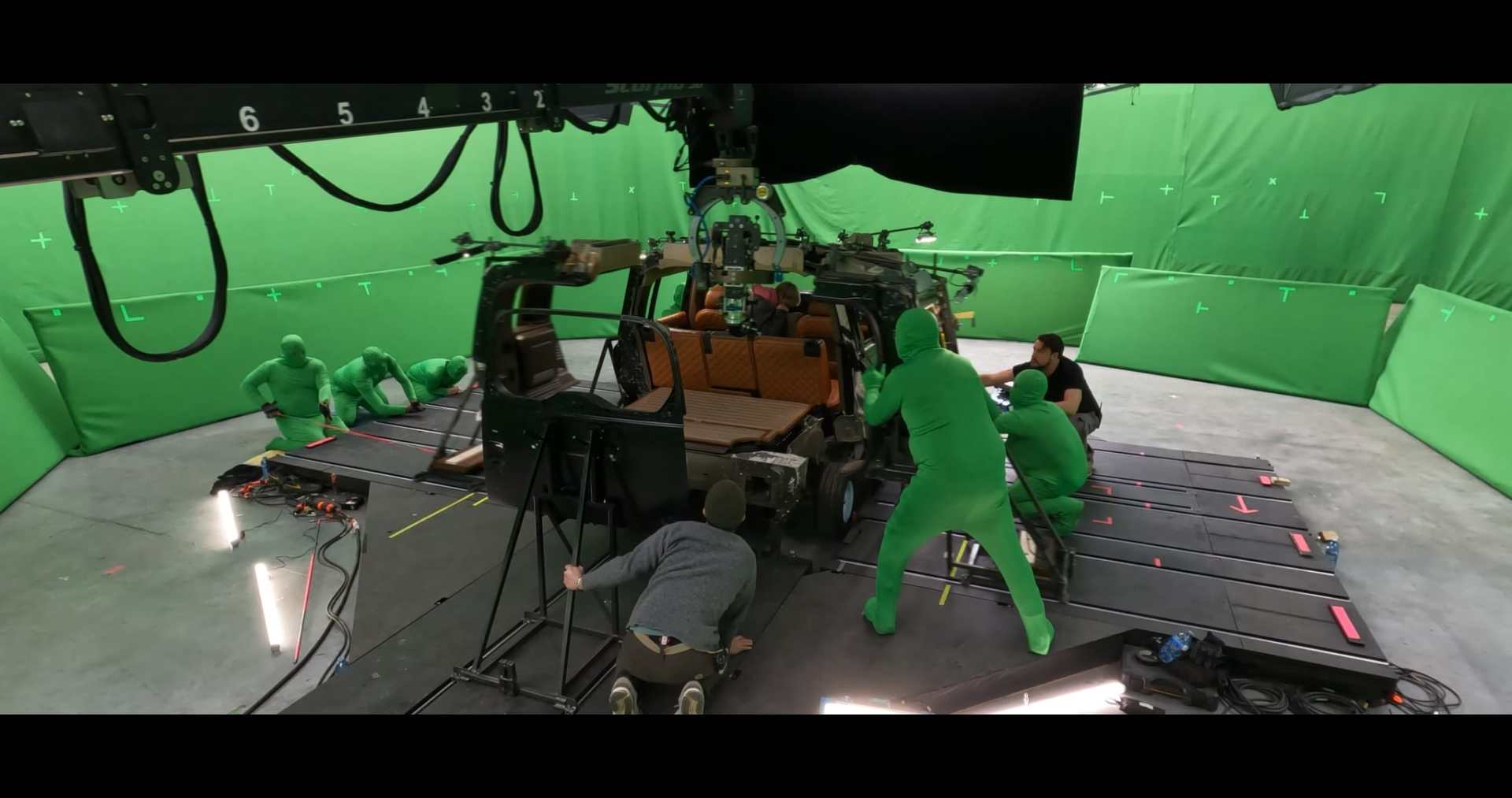

Jindrich Cervenka: At the beginning of the film, there’s a 3.5-minute shot where the camera circles around on a crane inside the car interior, which the crew gradually disassembles and reassembles to allow the camera to move smoothly. This was definitely the most difficult shot in the entire film.

The biggest issue was tracking. Because of the removable car walls, we couldn’t rely on the foreground and had to create two separate tracks—one for the background and one for the interior, where nothing stayed in place. We had to create reflections in the windows and side mirrors, and since none of the car walls were consistently in position, we ended up doing a lot of 2D cheats and manual adjustments.

Our matchmover did everything possible over three weeks of work, but even so, the glass constantly shifted slightly against the plates. It didn’t help that everything in the interior was curved and we had no clear edges around the window frames. This shot was a battle from start to finish. There were a huge number of retouches, keying, masking, and 3D renders. We dedicated a significant part of our Bratislava office to just this one shot, and its production ran in parallel with the rest of the film for almost the entire timeline.

We tried to make things easier by breaking the shot down into 96 smaller tasks, but in the end, someone still had to stitch it all together—and that compositor probably won’t forget it any time soon. Even reviewing the shot wasn’t easy. Each iteration required a lot of attention, and one round of notes could easily take me two hours.

It was one of those shots that kept evolving, with new details popping up even late in the process. But eventually, version 95 was marked as final.

DP: Was there a shot where you expected trouble, but it actually went super smooth?

Jindrich Cervenka: The bullet time shot really surprised me. We had to stitch together five different takes, and at first it looked like it wasn’t going to work—mainly because the camera rotation speeds were different and there were a lot of CG elements. But in the end, the shot actually went pretty smoothly. What we focused on most was the trajectory of the gummy bears – I’d say even more than the bullet itself. I think we genuinely enjoyed working on this one, in the fun sense of the word.

DP: Any takeaways from Locked that you’ll be applying to future projects?

Jindrich Cervenka: The project helped us most in thinking about how to organize and assign work across the different teams within the PFX group. Locked definitely pushed us a bit further in this area. What was crucial was getting oriented in the project as quickly as possible and passing on information efficiently. For dailies, we use an internal app that allows real-time review of any shot at any stage, either in the full context of the film or in a custom context we define. It lets us compare versions and shots side by side and publish notes directly to Ftrack, including status updates on individual tasks.

During our dailies, artists keep sending in versions right up to the last moment—even during the session itself. We can break down and evaluate any part of the project immediately, without caching or manually pulling things into the timeline. I try to keep everyone involved in the full context, and for me personally, it’s really distracting when I have to deal with technical stuff just to see the shots the way I need. In this app, I can do anything I need in 2 or 3 clicks—and everything works in real time.

DP: What’s your current “can’t-live-without-it” tool in your VFX pipeline?

Jindrich Cervenka: It’s the same app I mentioned in the previous paragraph—it’s called Crossbow. This app lets you break down a project to the smallest detail, bid it, plan production, and offers several different ways to create notes and comment on shots. It’s directly connected to Ftrack through a real-time two-way bridge. I use it for both client communication and internal communication, and with every project, we keep improving it. It’s been in development for four years now and is already very robust—I truly rely on it.

DP: If someone else had to pull off a similar car-only movie, what would be your top three tips to save their

Jindrich Cervenka: It’s always a matter of budget and the time available for the project. But in this case, I would recommend shooting a lot of the scenes in front of an LED screen. More than half of the film takes place in a car, and using an LED screen would have allowed us to capture many sequences directly in-camera.

DP: Got any upcoming projects where you’ll get to build on this pipeline — or are you already working on something completely different?

Jindrich Cervenka: Definitely—Locked was completed in Q4 of 2024. We work on many projects at once, and by now, we’ve moved even further ahead. Just a few days ago, I finished work on season 3 of Foundation, and right now I’m focusing on internal system development, taking a short break from projects for a few months. PFX has grown a bit, and with that, new challenges are showing up—some we’re currently dealing with, and some are still ahead of us.

1 comment

Comments are closed.