Table of Contents Show

Why use a light meter at all? When photographing with modern digital cameras today, you rarely need such a device if you are not using professional lighting. You simply shoot in RAW and expose to the right, i.e. to the highlights (ETTR), and do the rest on the computer. With film, the whole thing is not so simple: if you were to expose every shot in this way, you would have a massive jump in light with every cut, even in a simple shot-counter-shot situation.

Okay, you can hold the shot with the most intense light just before clipping the highlights and shoot the others with the same values – the rest will have to be dealt with in post-production. But if light is to be set or even just a few reflectors are to be used, then professional light measurement becomes very useful. It is just as helpful to be able to use such a device to judge what you need to bring along for good lighting when scouting for locations.

Why only iPhone and iPad here?

Light meter apps for Apple devices have been available for a long time, while the corresponding metadata was not accessible to developers on Android until recently. And then, Android still did not support metadata for colour. However, this is not only necessary for measuring the colour temperature, but also for evaluating the raw data during exposure measurement. Simply analysing the average image data is not enough for this, as the pre-processing of the camera images in the mobile phone distorts the values in an almost unpredictable way: the direct reading of the image data can lead to incorrect measurements of up to two f-stops.

Developers report about twice as much time spent developing professional apps for Android, but they only achieve 10 to 50 per cent of the revenue compared to iOS. It therefore makes much more sense to produce professional apps for iOS first. The limited selection of hardware also makes customer support considerably less of a hassle. This is probably also the reason why the Android version of the software for Lumu (see below) was withdrawn. In addition, developers of measuring devices of all kinds love the limited number of hardware constellations that they have to test in order to achieve reliable results. Of course, cameras and the rest of Apple’s electronics also have greater tolerances than dedicated professional devices – after all, top models such as a Gossen Starlite 2 cost around 550 euros, even though it fulfils this one task alone.

Nevertheless, we also tried out one of the apps tested here, namely myLightMeter Pro, on Android. We used a Motorola Moto E5, which can be considered a very affordable mid-range mobile phone. Not only did it show that the deviation was greater without calibration than with the iPhone. This would not be a problem for an app with calibration, but unfortunately linearity was also significantly worse. This means that after a calibration with medium brightness, the values in dark scenes deviate in one direction and in bright scenes in the other – this is not really useful. The inexhaustible number of such apps for Android and hardware with cameras of varying quality would turn a reasonably representative overview into an encyclopaedia anyway. (What the hell is an encyclopaedia?)

What is a dome?

There are basically two types of light measurement: that of incident light and that of reflected light. Without special accessories, a mobile phone only ever measures the light reflected by the subject, so you are responsible for either measuring on an official grey card (with 18% reflection) or estimating the optimum exposure yourself by measuring highlights and shadows. For professional lighting, on the other hand, it makes much more sense to use a measuring device to determine the incident light. In order to measure more than just the frontal incident light, such a device needs a translucent hemisphere made of neutral white plastic, as in one of our reference devices, the Sekonic.

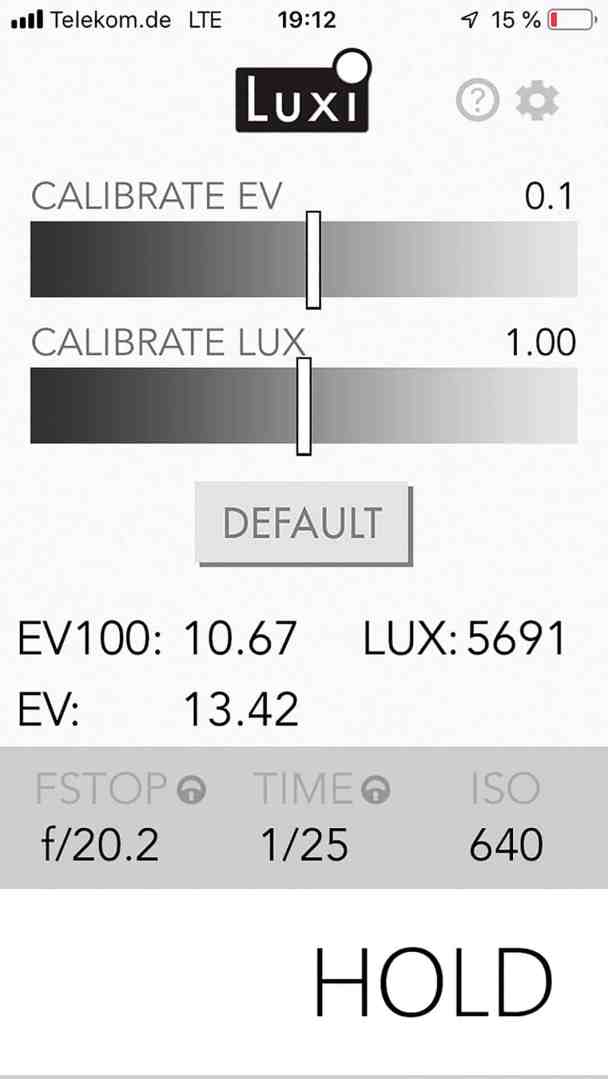

A Luxi is therefore certainly the most useful addition to the iPhone as a light meter. This is a white hemisphere made of plastic (the dome, see above), which is clipped onto the mobile phone and covers the front camera. The first model of this Kickstarter project is only suitable for some models such as the iPhone 4, 5 and SE and fits them very well. The only disadvantage of the older model is that it only fits properly if the protective cover is removed. The newer version called Luxi For All fits many mobile phone cameras and tablets, seems to be slightly less attenuating and is therefore about half an aperture more sensitive. It is also closer to the characteristics of a conventional light meter in its light distribution when light falls from the side, while the older model is slightly less sensitive to side light. However, you have to position the new Luxi just as precisely, and unfortunately it slips quite easily on the smooth surface of most devices in hectic everyday working life.

The approx. 25 euros charged for this may seem expensive for a simple piece of plastic. However, it was not only used to finance the production, but also the development of the suitable material and the free programme for it, which can also be used as a simple spot meter without the dome. Several of the professional programmes also work with the Luxi as a measuring device for incident light.

This already applies to the inexpensive myLightMeter Pro, and for Pocket Light Meter and Cine Meter II it is almost a matter of course, including a separate calibration. In principle, you can use any app that can be calibrated, because the dome absorbs some light. Just don’t forget to change the calibration again for spot measurement. By the way: The Luxis also fit on an iPod Touch if you don’t want to use your mobile phone. Another alternative to the light meter for those who despise mobile phones.

The candidates

One of our conditions was, of course, that the respective app still runs on the latest version of iOS, and we spared ourselves the trouble of taking our own measurements for apps with obviously devastatingly poor ratings from multiple users. However, the most important criterion for professional use is the ability to calibrate the app using a professional device as a reference. Understandably, the components for mobile phones are not manufactured or selected with the same tight tolerances that apply to a measuring device that costs several hundred euros just for this one task. Deviations are therefore to be expected from such devices without calibration.

Before calibration, our iPhone SE deviated from the average of the reference devices by around 1/3 f-stop, the iPad Pro by a good 2/3. In contrast, another sample of the SE was almost correct even without calibration. After calibrating as carefully as possible, we were particularly interested in the extent to which the devices still matched when the light intensity changed or when the temperature rose. There is a fairly wide selection of apps under iOS, ranging from simple, free programmes to freely available basic versions with advertising disabled or functional enhancements through in-app purchases to purely professional programmes. We have not included apps that first have to take a photo before anything can be measured. We have also not analysed various specialists for pinhole cameras, nighttime or long exposure photography.

How did we measure?

Our reference devices were a Sekonic L-508 Zoom Master, with which both spot metering and incident light metering are possible, and a Minolta Spot F with pure spot metering. Although both devices have been used in everyday shooting for a long time, they only differed by two to three tenths of a f-stop in the medium brightness range, which is quite insignificant. Most apps can only be calibrated in steps of 1/3 aperture, which is completely sufficient in practice – the aperture can hardly be set more precisely even on cinema lenses. Only Cine Meter II allows optional adjustment and display in 1/10 aperture. After adjustment at medium brightness values, both the iPhone SE and the iPad Pro matched the dedicated meters so well over a very wide aperture range that the display in this app did not deviate any further than the meters themselves.

In low light, these somewhat older meters were already “out of range”, while the app still delivered results that seemed plausible in comparison to the very light-sensitive Sony A7S. Similarly, an older iPhone 5 under iOS 9 still delivered precise results even in very bright light. Models such as the SE, which already contains the 6th generation camera, showed a deviation of 2/3 aperture upwards in very bright light. However, this was only the case in direct summer sunlight from behind on a white diffusion screen; the exposure was then around 9 EV above our grey card at medium brightness for the calibration. This phenomenon only affects the newer devices (or their iOS?), and at least Adam Wilt, the developer of Cine Meter II, is already getting to the bottom of this observation.

Some apps also measure the colour temperature. As we didn’t have a spectrometer available for testing – after all, a Sekonic C-700 Spectromaster costs around €1,300 – we compared this display with the measurements of some cameras. When using a Luxi, the measurements for daylight or incandescent light were quite good with a deviation of 200 to 300 K and quite sufficient for determining a suitable filter. With the more critical energy-saving lamps, the precision was worse, and it was also somewhat less accurate using a grey card.

For beginners and free of charge

With Lightmate by Luis Laugga, the easiest to use of the free offers, fans of classic photo cameras can certainly be happy. This is especially true if the in-built light meter has already died or batteries are no longer available. It is clearly laid out, very easy to understand and is capable of spot metering. Simply tap and wait until the metering circle stops flashing. The only disadvantage: as the values are displayed directly in the image, they are more difficult to read in bright areas of the image. Calibration is not possible, so you can only determine the deviation with a reference device and, if necessary, take it into account by setting a different ISO value. Film cameramen will miss the appropriate exposure times, but here the intermediate step of 1/45 second comes quite close to 1/48 or 1/50.

Lux – Professional Light Meter for Film Photography from Avicora allows calibration in 1/3 f-stops via the compensation value and is also quite clear and easy to use. However, contrary to what the name might suggest, it does not recognise the traditional film speed of 24 fps – this refers to analogue film in cameras. It does, however, offer 1/50th of a second or whole-numbered fractions thereof if the “Shutter Stops” setting is set to “Thirds”. This free and ad-free app is therefore also suitable for filmmakers, the only things missing are separate support for a dome, logging and the display of the colour temperature.

Affordable middle class

Light Meter – Street by Oliver Bojahr for 3.49 euros is one of the simplest of the commercially available products. It is based on the measurement of the camera image in the iPhone, but also allows spot measurements by tapping a point in the image. A simple recording button switches between continuous measurement and holding the current measurement. The display is very clear and, after entering the ISO value, you can easily display suitable time/aperture combinations; the last measurement is also saved when you exit the app. As a nice gag, the now almost forgotten mnemonic phrases are displayed in the style of “Sun laughs – aperture eight”. In American, this is called Sunny 16 (de.qwerty.wiki/wiki/Sunny_16_rule) – not because it is brighter there, but because the ISO values are taken into account. The app (as well as an English version) and the operating instructions on Github have been completely Germanised – the author is from here, after all. However, in favour of a quick overview, it only shows whole f-stops or EV values and does not offer any calibration options or film frequencies. On the iPad, the display can be rotated, but the camera image always remains in portrait format. This app is primarily suitable for photographers who are at war with the English language.

Pavel Bukhonov’s Light & Exposure Meter is ad-financed and can do much more. This app is also aimed more at photographers and is available in English and Russian. At least the values can be calibrated, albeit only in steps of 1/3 aperture and not separately for incident light with Luxi. It does not recognise film frequencies, but with 1/45 second you come very close to the standard exposure time. It can also display the colour temperature and log the values, even with thumbnail and location and time information. Unfortunately, you have to interrupt your work to upload or save the individual logs first. The often full-screen and time-controlled adverts for games interrupt your work even more and are extremely annoying if you don’t unlock the app for 5.49 euros. However, some reviews in the App Store suggest that adverts may still be displayed, which would border on fraud. An enquiry to the support address given in the store was unsuccessful, as our emails did not reach them – we therefore decided not to activate the app for testing.

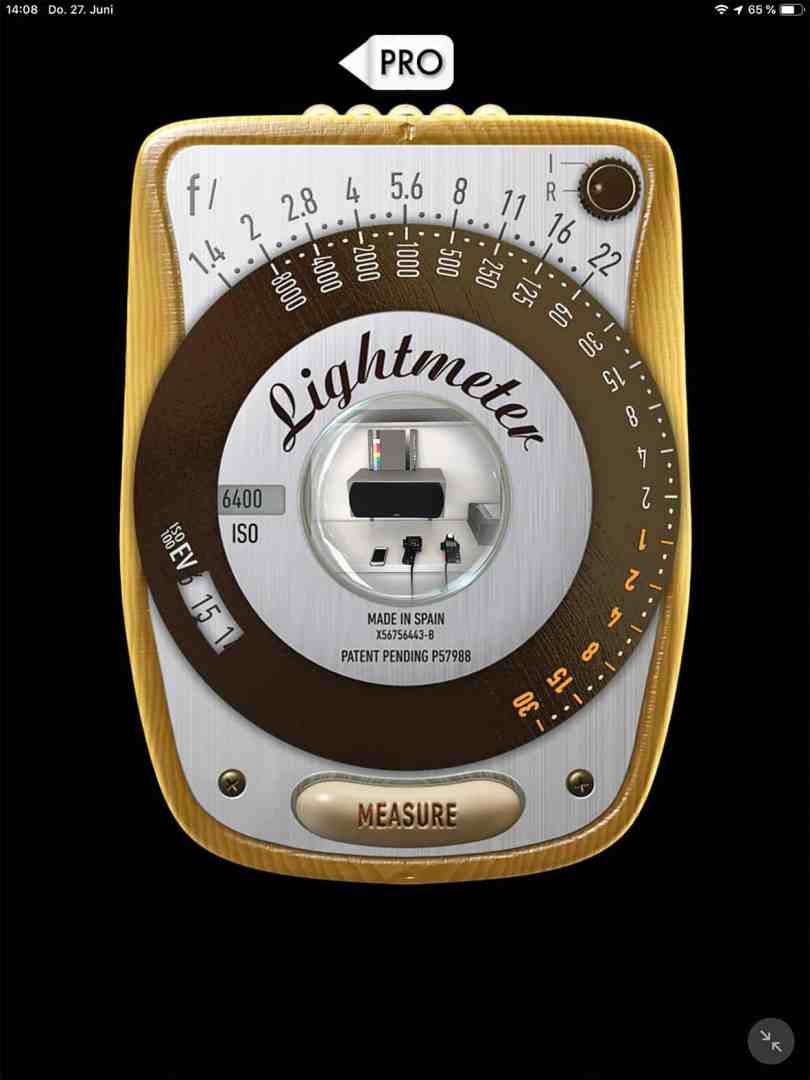

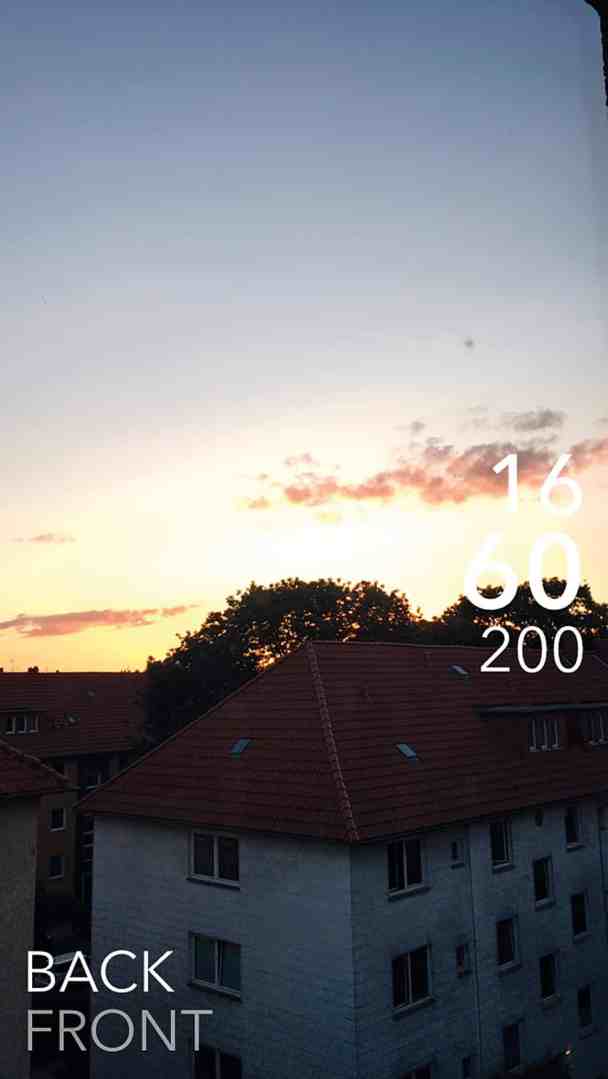

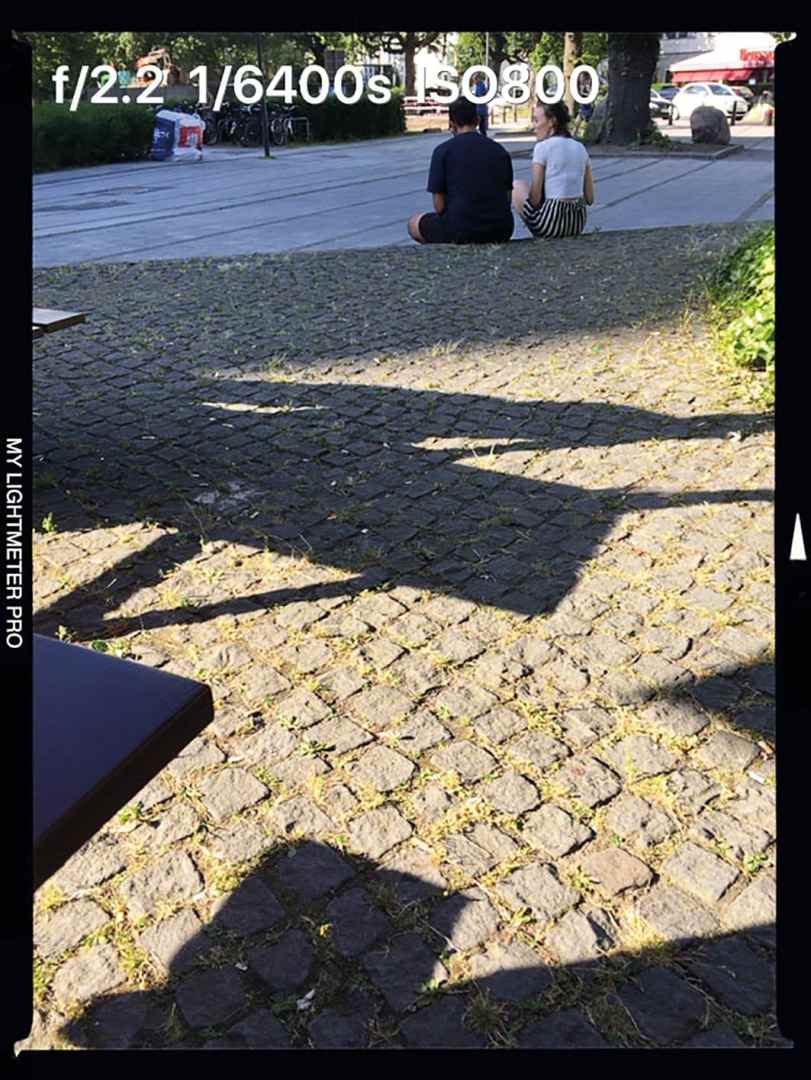

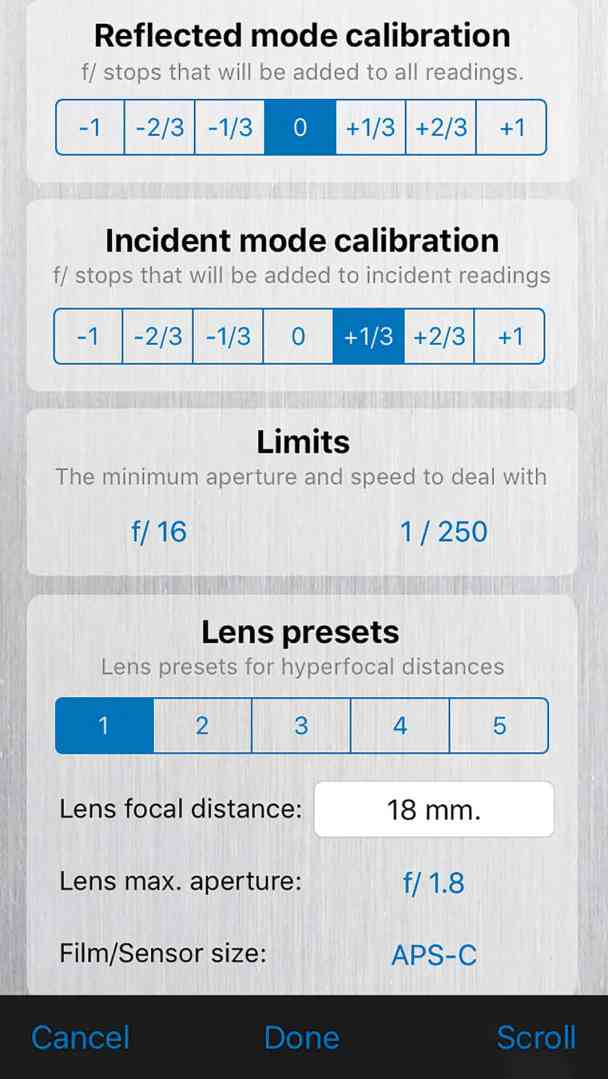

More serious is myLightMeter from David Quiles Amat, which simulates a beautifully designed vintage-style meter in the low-cost version for 2.29 euros (see Android). In the Pro version for 5.99 euros, it can do pretty much everything a photographer could wish for with spot and dome. There are also film frequencies, at least with 1/25, 1/50 etc., and the calibration in the settings is done separately for reflected and incident light (even if only in steps of 1/3 aperture). Separate exposure compensation for subject composition is offered directly in the meter. The app can calculate average values from several measurements, but there is no colour temperature measurement. Unfortunately, there is also no location or time information in the log function, which simply saves an image with exposure values in your own photo album. The “Read File” function allows you to read out the exposure of existing photos from your mobile phone, but without spot metering.

The unique selling point: it displays the hyperfocal distance for the selected aperture, even for infrared photography if required, and you can save up to five presets for your own lenses, taking the sensor size into account. The wealth of functions requires a little more learning, but there is a detailed instruction manual available for download as a PDF (English). The f/tools offered by the same author facilitate numerous photographic calculations, such as aspect ratios, cropping, motion blur, airy disc etc. and are also worth every penny at 1.09 euros. Both apps are obviously real hobby projects of the author and in this price range my recommendation (the Classic version is also available for Android).

The pros

Nuwaste Studios’ Pocket Light Meter, which used to be ad-supported, is now available for €11.99 without adverts. This is the cheapest app that can also display the typical film exposure time of 1/48 second and measure the colour temperature (uncalibrated). The measurement of the incident light can be calibrated in 1/3 f-stops, but unfortunately, despite the support of a Luxi, no separate calibration is offered for this – not an insignificant weakness. In addition, the app deviates a little more from the professional measuring devices than Cine Meter II in very low or very strong light. The greatest positive is the logging, which not only records all measured values, location, time, own notes and the respective image, but can even automatically store this information in a dropbox. With better calibration, this app would be perfect. However, if you only use one of the two measurement types regularly or change the correction value manually, you are already well equipped with this clear and easy-to-use app.

essentials.

with automatic upload is exemplary.

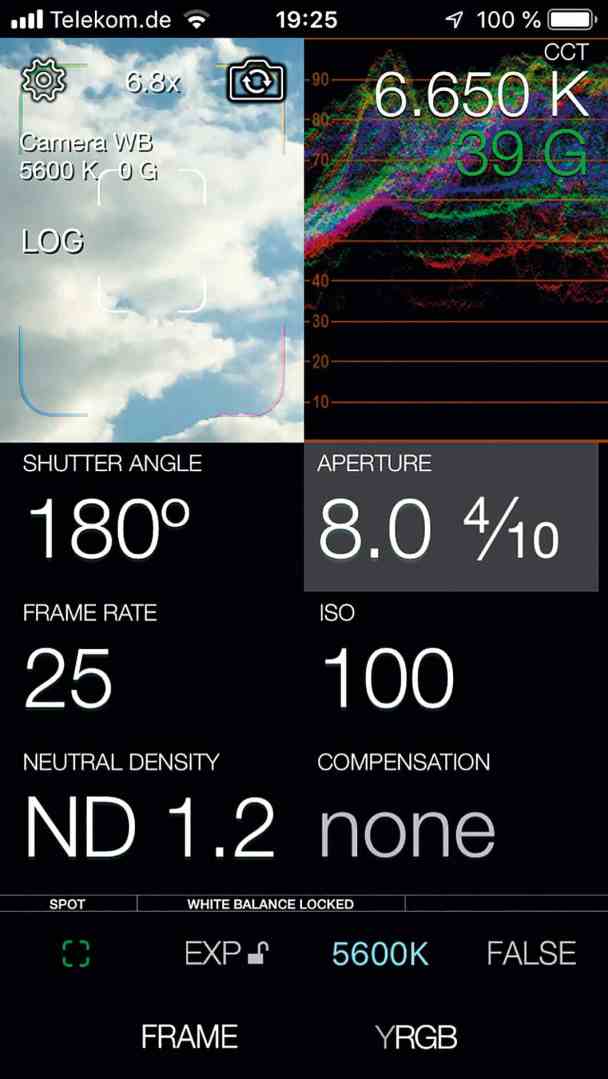

Cine Meter II by Adam Wilt is in the top class. Although it costs 30 euros, it leaves hardly anything to be desired. In addition to all the requirements already mentioned, not only the display but also the calibration can be carried out in 1/10 f-stops. The latter can also be performed separately for the front and rear cameras and separately for Luxi. The measured values are very precise after calibration and can keep up with the dedicated measuring devices (apart from the slight oversensitivity in full sun, which is probably due to the newer Apple hardware, see above). However, an accuracy of a tenth of an aperture is not a decisive criterion in practice, even a third of an aperture is good enough – which lens can be adjusted so precisely?

Cine Meter II can display the colour temperature and the green-magenta shift (also known as Duv) with Luxi or using a grey card from iOS 8, but of course it does not replace a spectrometer, as it is only based on a normal camera with three basic colours. The author explains the problems of such a colour measurement on his website: http://www.adamwilt.com/cinemeterii/colormetering.html (including detailed comparison tables). The calibration of the colour measurement is also described there. Based on this measurement, the app provides filter values for correction to the desired target value. Another typical feature of film is that you can specify a running speed and then set the aperture angle. Since, for aesthetic reasons, you usually don’t want to adjust the aperture or the time when there is too much light on film, you can specify an ND value instead.

apps for camera operators.

with Cine Meter II.

While the exposure measurement is very precise, the waveform and false colour display can only be used as relative values because they are influenced by the camera software. This is nevertheless very helpful if, for example, the even illumination of a green screen is to be checked. The only weakness of this app is the logging: the current values are only written to a CSV file at an adjustable interval. You then only have pure lists available, no images and no location information. However, a long press on the displayed image at least generates a screenshot. Nevertheless, logging in the manner of the Pocket Light Meter would be a very helpful further development. The complex yet intuitive user interface is explained with many practical tips on the author’s website, the links can be found directly in the app under “Help”.

Devices with their own electronics

Cine Meter II is the only device (apart from the manufacturer’s app) that also supports the Lumu Lite, including the colour trim function. Lumu is a Kickstarter project from Ljubljana in Slovenia, very nicely packaged with a leather case in black or silver, but unfortunately out of stock by now. It is a much more complex measuring device for incident light with its own sensor and electronics, which in its second incarnation as Lumu Power 2 is only built for Apple devices with a Lightning socket (the manufacturer will have good reasons for this). Unfortunately, the newer version no longer works with Cine Meter II and is available in different versions from 249 to 499 US dollars, taking into account the requirements of film professionals.

for Luxi.

Lumu Power is said to be more accurate than its predecessor with a maximum deviation of only 2/10 in lateral light, and it can also capture grazing light from behind, which is shielded by the mobile phone in the Luxi. Users praise the Lumu for better light sensitivity than many expensive light meters and very good temperature compensation. The rotatable dome makes it more flexible in use than the Luxi, and photographers appreciate the measurement of flash units, which an iPhone cannot provide. We have not yet been able to test the device, nor the Illuminati Light Meter. This goes one step further: the electronics are housed in a separate device for 299 US dollars and communicate with the app via Bluetooth. It is therefore independent of the direct connection to a mobile phone or tablet and its operating system or internal hardware.

Comment

Yes, you can use an iPhone as a professional light meter. If you want to keep all your options open, you need the Luxi, Pocket Light Meter for perfect logging and Cine Meter II for very precise measurements and filter determination. That would be around 65 euros, which is still far less than a solid light meter (without the mobile phone, but an old iPhone 4s or 5 will do).