This article by Sabine Hatzfeld originally appeared in DP 06 : 2014.

A special film school opened in Mannheim at the beginning of this year. The non-profit organisation “Flimmermenschen” views film as a holistic cultural phenomenon. The programme is aimed at students, hobbyists and people from outside the industry, as well as short film makers and trainees – such as media designers for image and sound – who want to deepen their knowledge.

Behind the “Flimmermenschen” association is Dr Marc Reisner, a video artist and director(www.flimmermenschen.de). Reisner has produced over 100 intermedia theatre productions to date, from 3D and 2D to 16-millimetre film. He has worked with Christoph Schlingensief, Achim Freyer and Jimmy de Brabant, among others, and has already realised a theatre production in a real-time bluebox with 3D backgrounds.

He has also been teaching theatre, film and 3D animation at universities since 2000. He has noticed that many of his students are more film fans than film connoisseurs, and that the universities are training the film-making elite. But what happens to the rest? With the model maker who is interested in 3D printing? With the short film maker who wants to learn about VFX? Or students who want to know how an animation studio works?

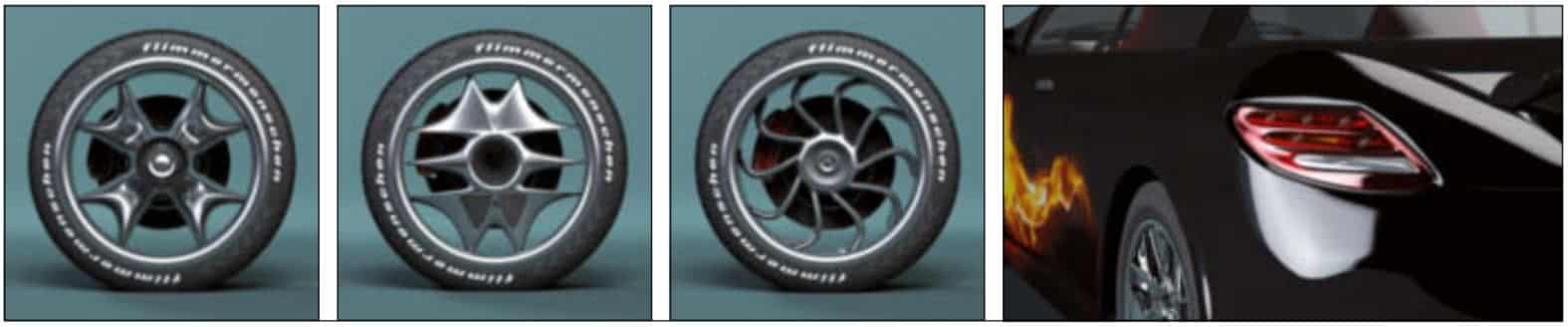

The idea of founding an association was born and the first half of the year was characterised by the pilot project “Polygon Racing”. This was not only about designing and animating cars, but the participants also investigated the laws of physics and turned their attention to topics such as the cultural adaptation of trailers or the merchandising concept of Disney/Pixar’s “Cars”. The subject of film is thus examined from several different angles. The course costs are quite reasonable and are on a VHS level: participants paid a total of 150 euros for twelve evenings over three months and received a certificate of attendance at the end of the course. This course was offered twice and there was also an expert course. This marked the end of the pilot phase. From September, the Flimmermenschen will then expand their programme to eight workshops. We spoke to Marc Reisner about the organisation’s concept and its plans.

DP: What exactly do you criticise about the current training situation? Marc Reisner: There are media education projects and film schools, but nothing in between. I like to use a football club as a comparison: not everyone wants to become a professional footballer, but even amateurs don’t want to remain at ball-stopping level, but perhaps achieve more. In other words, not everyone who studies film wants to become a filmmaker later on. But they also don’t want to sit in front of a trick box all day or have someone who has never been on a film set explain to them how to make a film. Universities only train the top end of the film industry. But who takes care of the rest?

DP: How did the organisation come about?

Marc Reisner: The association was founded in Mannheim at the beginning of the year. For years, everyone has been saying that Mannheim is the city of music, but that something needs to be done about moving images. There are a lot of great funding opportunities in Germany, but if you get little or nothing from them, it can happen that nobody gets moving. That’s why I said last year: we’ll just do it now. My experience in the theatre has shown that once the ball starts rolling, a lot of things happen by themselves.

DP: What is your goal?

Marc Reisner: Of the hundreds of students I’ve taught so far, almost all were film fans. But none of them had the slightest understanding of film. Most film schools have the same problem: People apply who can list film titles but don’t know what happens in the 90 minutes in aesthetic and technical terms. But that’s only one aspect. Conversely, the medium of film influences our language and shapes our role models. The mobile phone was invented by an Enterprise fan, Dr Martin Cooper. Minority Report” showed us what good, interactive design is all about. The disco boom was triggered by “Saturday Night Fever”. You don’t even have to go to the cinema to be influenced by film. Our society breathes film.

DP: The advisory board is made up exclusively of academics – what about industry professionals?

Marc Reisner: Our target group is people who are interested in film for whatever reason, who want to learn more about it or who are looking to enter the industry. Didactic concepts are also of particular interest to us. Hence the scientists. We have the professionals on board through the advocates.

DP: Your first course “Polygon Racing” is designed to teach 3D knowledge to non-professionals. But isn’t that what 3D professionals are for?

Marc Reisner: Exactly. That brings us back to the football club. In our first course, for example, there was a set designer who wanted to spice up his models. He bought a 3D printer for this purpose. Building a propeller out of wood is pretty time-consuming; printing one out is not. You don’t always have to think of Hollywood films to make good use of 3D. Another course participant from the automotive industry has a lot to do with Previs in order to explain the functionality of industrial robots, which are difficult to take to customers. An agency would charge huge sums for a virtual representation, but the participant is now so fit that he can produce simple visualisations himself. This saves time and money and does not result in any transfer losses.

DP: Do you also target young people who are interested in training in the field of animation/VFX?

Marc Reisner: Most young people watch a Pixar film and then think that they want to do this professionally because animation is cool. We give them an overview of how an animation studio is organised, which departments are involved and what the basic work steps are. If you know afterwards that you’d rather study graphic design after all, you’ve already gained something. As I said before, my impression is that most young people have no idea what it means to work in the film industry. This is precisely the knowledge we want to impart.

DP: To what extent could professionals also benefit from a course?

Marc Reisner: The expert course is not intended for real 3D professionals, but for those who have completed the basic course and already have a basic knowledge of 3D. We don’t want to train digital artists, we just want to open doors. There are plenty of training opportunities for 3D artists. To be honest: far too many.

DP: How is Flimmermenschen financed as a non-profit organisation?

Marc Reisner: Through donations, voluntary work and small grants from the city. We are also generously supported by Musikpark Mannheim through the premises they provide and by Autodesk, Adobe and Dosch Design.

DP: How do you communicate real conditions in the industry?

Marc Reisner: As I have shot a lot myself and also taught lighting for a long time, I would like to bring in real film practice. At the moment, however, there is still a lack of equipment in every nook and cranny. Our first course also focussed on 3D because the technical requirements in this area are somewhat lower. Real framework conditions are demonstrated using examples from current cinema films. In “Polygon Racing” we take a detailed look at “Rush” and work out with the participants what 3D is actually needed for in the cinema. There will also be “Flimmertalks”, where film-makers will talk about their day-to-day work, such as Chris Vogt from Pixomondo.

DP: With “Polygon Racing”, you combined animation knowledge with expertise from collaborations with racing drivers and car specialists – but is that how all the big studios work? Why do you think your approach is so special?

Marc Reisner: Because we are not a film studio and it is sensational for the average German to think outside the box. It may be normal for film-makers to absorb the topic they are currently working on. However, many students or people from outside the field first have to take this step. Which brings us back to the topic of methodology: How do you find out where the centre of rotation of a car is when it is moving around a bend? We filmed with a chassis designer who explained this. And then every course participant was able to try it out for themselves.

DP: Why is “Polygon Racing” being offered in a different form in the new programme?

Marc Reisner: There are several reasons for this. Firstly, we have received a few enquiries from outside the city. People who don’t live in Mannheim won’t be travelling to us once a week for two hours. It was therefore clear that we had to offer our courses in blocks if we wanted to appeal to people from the surrounding area. Secondly, I myself had the feeling that the course was becoming more and more like software training. And that’s exactly what we don’t want to offer. We want to demonstrate the concepts and not spend hours clicking buttons.

DP: Who are your lecturers?

Marc Reisner: I taught “Polygon Racing” on my own. That was our pilot project, which allowed us to try out a lot of things. As I said, from the autumn we will be switching to a workshop programme with courses running from Friday lunchtime to Saturday evening. As a result, we have also been able to attract lecturers who simply take a weekend off for us. For example, director and digital artist Andreas Dahn will be coming along and doing something on the subject of VFX planning. Music video legend Robert Bröllochs will also honour us (editor’s note: Modern Talking, Scooter, Xavier Naidoo …) and offer something on the subject of filming with amateur actors. Together with Tilman Bischoff from “Planet Schule”, I’m currently developing a course on space physics and cinema. “Gravity”, for example, is very much about realism, but in the decisive scene the dramaturgical element prevails. That’s why we want to ask the ESA what materials an astronaut’s safety rope is actually made of. There certainly isn’t one like the one in “Gravity” in reality.

DP: What hardware is the “einsnull” spacecraft equipped with?

Marc Reisner: There are eight iMacs (i5, with 8 GB). They are all networked together and as a lecturer I can access every computer. If you’re working with young people, you can always put two on one computer. The adults prefer to try things out for themselves.

DP: Which software packages do you work with?

Marc Reisner: As we are sponsored by Autodesk and Adobe, we work with Maya and the usual suspects such as Photoshop, After Effects and so on. For our space project, we realised that physicists can’t do very much with the rigid bodies in Maya. That’s why we are once again looking for software that allows physically correct simulations. We also have a direct line to Sebastian Dosch from Dosch Design, who provides us with everything our hearts desire. Autodesk is an important partner for us, because they have a lot of experience with 3D programmes at the intermediate level, especially in the English-speaking world. We were able to learn a lot from them, for example how to use Maya for biology lessons. In any case, people in America like to work on a project basis, which is very similar to our approach. In Germany, practically nobody dares to tackle the subject. It only starts at university level.

DP: What’s the deal with the Flimmertalks?

Marc Reisner: We organise these guest lectures for the public in cooperation with the Cineplex Mannheim. Anyone who wants to can come. In terms of the film industry, Mannheim is not exactly the centre of the universe. Therefore, there are many interested people who are not necessarily interested in our course programme. As we are a non-profit organisation, I think it makes sense to say: “We have people who have something to tell. Come and listen. Regardless of whether you attend our workshops or not.” It’s important to us that you can simply experience what it means to work in the film industry and to be “on fire” for your job. Many people still think that you go there, shoot a bit of film and spend most of your time lying by the pool. Especially outside the professional world, a frightening number of people still equate mobile phone videos with cinema films. It’s kind of the same thing, they say, they just have more money in Hollywood. They never talk about performance, blood and tears. That’s why we had Uwe Boll on in the last Flimmertalk – we know all about his reputation as a director. But he is someone who makes films and doesn’t talk about projects that never come to fruition because nobody wants to pay for them. His talk made a lasting impression on many members of the audience, as it was suddenly no longer about the quality of his films, but about how to get big projects off the ground. As a producer, he currently has a film in the pipeline with Antonio Banderas and Gwyneth Paltrow, namely the film adaptation of Picasso’s life (directed by Carlos Saura). He really had a lot to tell.

DP: What are your contacts with studios like Pixar?

Marc Reisner: Pixar, Pixomondo and many others are just a phone call away. That’s our unofficial technical and content support, so to speak. For example, Tanja Krampfert from Pixar supported us in the development of our first course “Polygon Racing”. Some of the participants are currently undergoing vocational orientation – we have students who are still familiarising themselves with the buttons on the mouse. So you have to realistically question what they can learn from a full professional if they are still struggling with the basics.

DP: What is the role of the organisation’s advocates?

Marc Reisner: If you make the bold statement that film has something to do with culture, you will quickly realise that all areas of cultural education are occupied by the long-established institutions: Theatres, museums, music schools. That’s why it’s important first of all to bring people together to stand in front of us and say: film is important too. Film is also culture! The advocates are all people who are really committed to our cause. Some of them will also be giving workshops in the new seminar programme, such as the film director Stefan Hillebrand or Robert Bröllochs, as already mentioned.

DP: Why are there only a few people from the 3D industry listed in the programme?

Marc Reisner: Quite simply, it’s about anchoring the flicker people in the region. All the advocates come from the Rhine-Neckar metropolitan region or have at least worked here before. The advocates are primarily there to show regional politicians that they support our concept of film education. An artistic director of the National Theatre is more effective than a 3D artist from England.

DP: Is the principle of “Polygon Racing” transferable to other subject areas and are you planning to expand the range of courses?

Marc Reisner: Definitely. As I said, we started out in the virtual world because it offered many structural advantages. We are now extending the findings from the course to other subject areas: For example, there have been numerous requests for us to do something like a “basic film course”. So not a course where you learn what a long shot or close-up is, but one that explains how film works in the first place. We forget far too quickly that we are used to watching films. But a Martian would ask: “What does that have to do with reality? The film has an edge, and you can’t touch the woman in the shower, and nothing is wet here. It’s actually just moving blobs of colour.”