Motion Spell is the exclusive commercial licensor of the GPAC Open-Source Software – a software project centered around data packaging. “GPAC Project on Advanced Content” is a software offering a modular multimedia framework for packaging, streaming, inspecting and playing content; it provides tools for processing media content.

To put it in layman’s terms what GPAC actually is: It concerns a software for sending rich-media and broadcast content; rich-media describing interactive media content (like an interactive advertising banner on the web), and broadcasting content being prominently utilized by streaming services like Netflix and its competitors. In its self-presentation, Motion Spell further explains how “GPAC is best-known for its wide MP4/ISOBMFF capabilities and is popular among video enthusiasts, academic researchers, standardization bodies and professional broadcasters.”

Romain is an alumnus of Grenoble INP (École nationale supérieure d’informatique et de mathématiques appliquées), where he graduated with a Master’s degree in Computer Science. Romain

He is a self-proclaimed Open-Source Evangelist, Video Streaming & Broadcast Technology Entrepreneur and Advocate for Open Standards. His career began in 2009, when he joined Télécom ParisTech as a Research Engineer, where he accompanied experts on standardization in the media industry – and started building GPAC. By 2012, Romain switched to VideoStitch (renamed to Orah in 2017).

As the company’s name signifies, VideoStitch focused on video stitching – but it has broadened its services to 360 video and VR content creation since then. The most important software developed at Orah are: VideoStitch Studio, Vahana VR (a live stitching software) and Orah 4i (a live VR camera). During his time at Orah, Romain was responsible for architecture, development, coordination and delivery of the very first version of VideoStitch Studio. In the year 2012, Romain founded Motion Spell, where he – next to his duties as CEO – advocated the use of open-source software in commercial broadcast, video streaming, OTT and VR applications (for additional information about GPAC Licensing, read here: is.gd/GPACLicensing).

DP: Give me the sales pitch for GPAC!

Romain Bouqueau: GPAC is an open-source software. I would even go so far and say GPAC is not a software – but a project. A project focused on packaging. The majority of GPAC’s development is based on the ISOBM FF (ISO base media file format). ISOBMFF was developed in the nineties by Apple. Apple was one of these companies pioneering many media creation technologies, like Quick Time VR. The end of the nineties was a central period for the arts and creativity, when Second Life was a thing, for example – it was the Dotcom era. Back then, ISOBMFF was not ready yet, but the vision was promising. And that’s when both ISOBMFF and GPAC were born.

ISO, the International Organization for Standardization, had already MPEG for moving pictures. ISO wanted to move away from 2D-TV stuff, to something more accessible and interactive. They were unsure, but created a set of standards in the process, that people know today as MPEG-4.

Curiously, the ISOBMFF is something Apple gave away as a royalty free technology. Apple was a pioneer in that sense. Hence, Apple made ISOBMFF royalty free for ISO. As a consequence, ISO developed MPEG-4 inside ISOBMFF. This base media file format contains everything media related. GPAC is specialized in this.

So, GPAC started as a startup in New York City during the dotcom era. A few years later, by a conjunction of factors, GPAC became open source. That’s where our story begins.

GPAC has to offer are packaging, encrypting, streaming, inspecting and playback of media content.

DP: What conjunction of factors led to GPAC becoming open source?

Romain Bouqueau: The dotcom era ended. The economic crisis crushed many startups. The company where GPAC was initially developed collapsed; it was called AVIPIX, LLC and was based in New York City. But the software was very promising. Actually, some of the users based at Télécom ParisTech, the prestigious engineering school attached to the historic national telecom operator France Telecom, contacted the developers behind the software and said: “We would be interested in using your software as a research platform.”

Télécom ParisTech had issues losing control over the IP of some software they had produced. Free Software Licenses were still quite novel at the time. Those students had IP issues with their own code. You have to know: They had an equivalent code inside the university. They said: “We don’t want this to happen again. So, we would like it to be open sourced with a GNU General Public License – to make sure we can always use our own codes, and further develop it.

DP: How did you become involved with GPAC personally?

Romain Bouqueau: I was really interested in the free software movement. I was a musician. I’ve spent 10 years at the national music school C.R.R. Nice, and was very passionate about classical and organic music.

In parallel, when I was 12, we got a computer at home. I knew that these computers were programmable. About a year later, my father offered me a book about the C programming languages. Honestly, this was out of reach for a 12-year-old with no one to help. But that’s when the idea started to infuse. Then some students from the local university came home with a set of floppy disks containing the Linux operating system and the GCC Compiler. That’s how I learned about the Free Software movement.

Years later, after a BSc in Physical Sciences at Grenoble INP (École nationale supérieure d’informatique et de mathématiques appliquées), I shifted to Applied Mathematics and Computer Science. My wish was to work on audio signal processing. But at that time, I was located in a small city and my only option was to take this internship at Allegro DVT, a company doing video streaming (Romain worked there from 2005 until 2009. Editor’s note). That’s how I came from audio to video. Then, within this company, we did IPTV (Internet Protocol Television) – it was sort of the beginning of IP-related stuff with video. Back then, the company was a really small startup that is now part of ATEME (which is a company focused on software for video compression. Editor’s note).

GPAC was developed at Télécom ParisTech. I started contributing to GPAC there (Romain was a research engineer at Télécom ParisTech for three years, from 2009 until 2012. Editor’s note). And with digital video, they not only wanted to introduce the digital aspect, but also interactivity – via audience feedback for your content, for example. At the time, we were using GPAC for that. This was really complex, since the networks were not on IPs, but on hybrids between something that would be like 2G Edge or 3G using broadcast

channels.

There was a project about enriching radio when moving the transmission to digital. This project was using GPAC. I knew it was free software. One day, while struggling with the technology, we discovered the project was maintained at Télécom ParisTech. We invited two researchers for a training – one of them was the founder of Avipix, Jean Le Feuvre. When I met this guy, that’s when the story started. They proposed me a grant to work on GPAC. So, I started to work as a professional open-source developer, and then, three years later, I set up my company Motion Spell.

DP: What led you to the founding of Motion Spell?

Romain Bouqueau: Before 2008, GPAC had a strong focus on creative technologies such as 3D, scene rendering with BIFS and SVG. GPAC can manipulate a lot of objects in a way similar to a browser. We had a wide audience. Those were researchers, students and PhDs, video enthusiasts, but mainly pirates… these pirates became CTOs or founders of today’s digital video industry.

GPAC was an open-source project funded by a public entity. There was not enough money there, so we were pushed to look for partnerships with industrial partners. However, our employer was slow and therefore inefficient to close deals. That’s how GPAC came to focus on OTT trends. And that’s why I decided to launch a licensing offer with professional services for the commercial users of GPAC.

When I entered the team as a professional developer, I said: “There are two things. One, I think, is that we have the potential to raise our audience. And two, we should focus on securing some funding.” I said that, because university was not a place where we could get a substantial amount of money, which we would need as a starting-off point to do things. We required more money, since we required more servers for testing our software – and we needed more devices. In those days, mobile devices were arriving on the market. Consequently, we were in dire need of some funding, but the university was not sufficient.

in the process.

Universities do not provide a good structure to handle commercial deals. They don’t provide the support, they’re really slow negotiators, and the same applies to legal affairs; sometimes it takes months to get feedback. Because of that, we needed something smaller, faster – something more appropriate for commercial users. Also, I wanted to build it cooperatively, so that the people contributing to the open-source software would get proper compensation.

Our developments were based on the MPEG-4 technology, but we were also contributing to GPAC. At some point, we said: “Okay, the MPEG-4 wave is fading. Everybody is using H.264 as a video codec. Everybody is using AAC as an audio codec. Everybody started using MP4 and fragmented MP4 with MPEG-DASH.“ We could see the convergence of it, and its great success. We felt there would be a new technology generation for streaming content over IP networks – that would be unidirectional. That would be what we call OTT today.

DP: GPAC consists of two toolboxes: Multimedia Packagers (MP4Box) and Multimedia Player (MP4Client).

How does this work?

Romain Bouqueau: When developing new technology, you need to be end-to-end. If there is a new technology, and you build an encoder for it. If you have a technology that is on the decoding side, you need an encoder to get some streams. We at Motion Spell are focused a lot on R&D, the standardization, and deployment-ready implementation.

If we wanted GPAC to be self-sufficient, we needed to have the packaging and the playback. Now, we have all of this. It’s integrated into one big piece of software. It consists of media blocks that get connected to one another. For example, a media block will ask a player for displaying or rendering. That’s the media pipeline. It enables you to stream content or play it back.

(see also the corresponding news item on the Streaming Media Blog from Dan Rayburn at is.gd/GPACNetflix)

DP: In 2003, GPAC was made available as open-source. What milestones did GPAC go through since then?

Romain Bouqueau: Open-sourcing was perhaps the biggest milestone. After that, it got rapidly adapted as the recommended MP4Muxer of the x264 video encoder. This was important, because x264 was a huge success and it broadened our audience.

Around 2010, support for the OTT streaming technologies HLS and MPEG-DASH emerged. That’s what happened prior to founding my company, Motion Spell (which was founded in 2012. Editor’s note).

GPAC is pretty big. It’s 20 years of development, it’s around $20 million put in development over those years. It consists of a million lines of code. You have to make GPAC right, because otherwise, the maintenance becomes a burden.

In 2020, there was another milestone, when we, as Motion Spell, moved from our “set of tools with different functions” to a “set of modules”. Now, you’re just plugging modules together. People used to utilize

our packager, which was called MP4 box – that’s our main tool. But we are continuously moving away from the “single application model”.

In its most current iteration, GPAC allows you to have graphs. Let’s say you want a special effect. You can say: “I want this type of input. I want this special effect.” GPAC is putting all the bricks together. It’s inferring: “What are the missing bricks?”, and will make you different proposals as a consequence. But if you, as the user, are unhappy with GPAC’s solution, you can change the command line to your wish.

Regarding scripting, this is something we have extensively reworked for GPAC 2.0. It enables you to use scripting for everything – using Javascript, Python, and soon other languages like Go or C#. That allows the user to change the signal processing without dealing with the GPAC‘s code. The signal could be connected to effects or animations – but also streaming formats, or VR-related applications. As a result, there are a lot of different use cases.

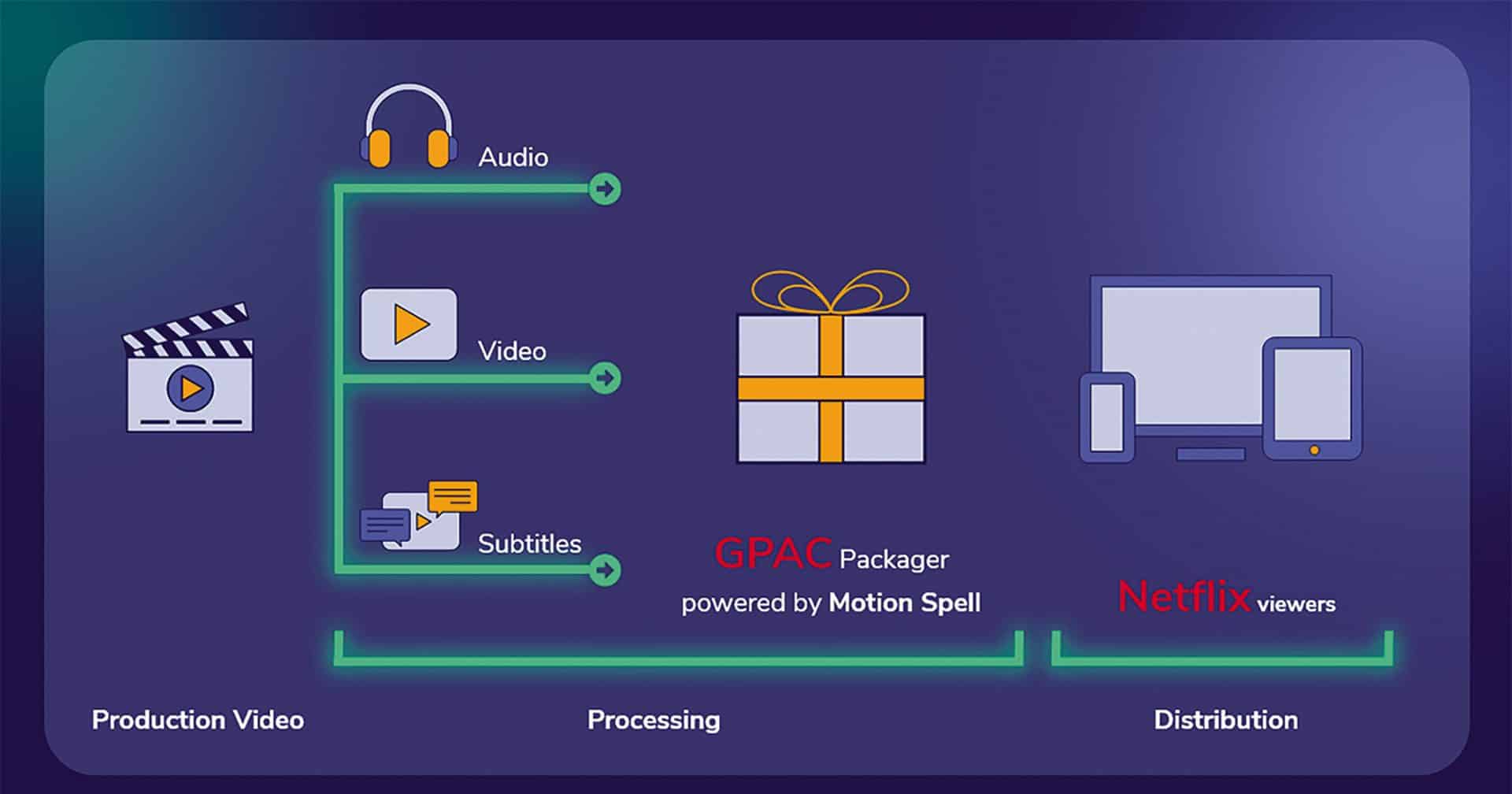

DP: After an 18-month transition with Netflix, for the integration of GPAC Open-Source Software into Netflix’s worldwide content operations, the process finally succeeded. What was that like?

Romain Bouqueau: You have to know: There are many GPAC contributors! It used to be a packager for YouTube before Google did their own packaging. There were many projects and businesses build on top of GPAC. I think that’s part of the reason why Netflix wanted to use it. After some discussion and testing in tandem with Netflix, they said: “Okay, we’re going to deploy GPAC.” That’s when the 18-month phase started.

It’s important to understand that Netflix is a metrics-driven company, which makes them a bit of an outlier on the streaming market – in my opinion. If Netflix notices an increase in re-buffering or users jumping off watching the episode of a show right in the middle, they can infer an underlying problem. The same applies to when the metrics improve. A better packager will result in better caching, less latency, and reduced loading times.

For Motion Spell, as an open-source business, we’re here to help. Netflix saw GPAC as a good fit; if Netflix has questions, we provide professional services. GPAC allows Netflix to be flexible. For example, Netflix just announced a few days ago they would stream their first live-show (see the news item by Jenny Priestley at tvbeurope.com: is.gd/NetflixLiveStreaming. Editor’s note).

If there are constraints with the open-source license, you can buy the commercial license. The open-source version comes without any licensing fees. The important thing is: Depending on the quality of a client’s packaging, the distribution comes with attached costs. If the packaging is not sufficient, the client is distributing more bits than needed. For a company at the scale of Netflix, distributing less bits means saving costs.

DP: What are some of the major pain points with GPAC right now?

Romain Bouqueau: There is going to be a new release, which will have Dolby Vision support. Otherwise, GPAC is really stable. There are few issues. We use our resources for writing code efficient. It’s all battle-tested. I encourage users to test it.

On the packaging side, there is ProRes and HDR stuff. We have good support for metadata, where ISOBMFF is not the main format for production, but alternatives like IMF. For companies with limited scale and resources, it makes perfect sense to go back to ISOBMFF, which allows them to use the same platform for dealing with their content and distribution. For example, if a client is storing content using ProRes, they can use GPAC to enable ProRes; they can leverage the metadata (like GPAC’s capabilities of annotating content). You can use GPAC to prepare your content for streaming. Button line is: You can re-use components between different workflows. As I said, I think that makes sense for smaller businesses.

DP: Motion Spell also provides consulting for Netflix’s R&D division, right?

Romain Bouqueau: Yes. When people have problems, they report this via Netflix backtracker, so that we can investigate cooperatively. Having said that, the big problems are already solved.

Netflix has so many different users, so many metrics, so many end devices, so many different versions of its content. For us at Motion Spell, it allows us to see many different cases at the same place. This is not about issues raised by different users over a long time period. Smaller businesses than Netflix struggle with the multiplication of contents and devices.

Most companies use GPAC, but they rarely talk about it publicly. A few days before our press release was published, announcing our collaboration with Netflix, Facebook made an announcement – about Instagram facing infrastructural problems. Those problems prevented users from uploading videos. The issue behind this is a scaling issue on the infrastructure. Facing that problem, Facebook was able to reduce the computing needs by 94 percent. What they did is: Instead of transcoding everything, they used the GPAC packager. Facebook communicated this via its tech blog openly (read at: is.gd/InstagramEncoding, blog article by Software Engineering Manager Ryan Peterman and Software Engineer Haixia Shi. Editor’s note).

In order to maintain GPAC and add features, we need 5 percent of 14 million every year, which is 700,000 US-Dollars needed every year. That’s a lot of money – but that’s just for infrastructure. We don’t finance ourselves through advertisements. The money comes from somewhere else. To give you an example: There are prominent people from universities supporting GPAC’s research, It’s Motion Spell’s job to secure commercial users and shed light on its benefits (to learn how costs are estimate for GPAC: is.gd/GPAC_CostCalculator. Editor’s note).

In general, there is less funding in this type of technology, as compared to others. Most companies simply conceive of GPAC as open-source infrastructure not in need of any support. Having said that: A small number of companies understands the importance of this and contributes.

DP: If GPAC and Motion Spell are off your mind – what do you enjoy watching on Netflix, Romain?

Romain Bouqueau: I really like the Bandersnatch episode of Black Mirror. It’s an interactive episode, which excites me as a technologist. It was released in December 2018.

Terminology mentioned

An overview of the most important abbreviations and technical terms mentioned during the interview. Source: Wikipedia.org

2G: Is the short notation for second-generation cellular network, a group of technology standards employed for cellular networks.

3G: Is the third generation of wireless mobile telecommunications technology. It is the upgrade over 2G, 2.5G, GPRS and 2.75G EDGE networks, offering faster data transfer, and better voice quality.

Advanced Audio Coding (AAC): Is an audio coding standard for lossy digital audio compression. Designed to be the successor of the MP3 format, AAC generally achieves higher sound quality than MP3 encoders at the same bit rate.

C Programming Language: Is a general-purpose programming language created by computer scientist Dennis MacAlistair Ritchie.

Dynamic Adaptive Streaming over HTTP, also known as MPEG-DASH: Is an adaptive bitrate streaming technique that enables high quality streaming of media content over the Internet delivered from conventional HTTP web servers.

FFmpeg: Is a free and open-source software project consisting of a suite of libraries and programs for handling video, audio, and other multimedia files and streams.

GNU General Public License: Is a series of free software licenses that guarantee end users the freedom to run, study, share, and modify software.

H.264/MPEG-4 AVC: Is a video compression standard based on block-oriented, motion-compensated coding

HTTP Live Streaming, also known as HLS: Is an HTTP-based adaptive bitrate streaming communications protocol developed by Apple and released in 2009. Support for the protocol is widespread in media players, web browsers, mobile devices, and streaming media servers.

IPTV (Internet Protocol Television): Describes the delivery of television content over Internet Protocol (IP) networks. This is in contrast to delivery through traditional terrestrial, satellite, and cable television formats.

IMF file format: Is an audio file format created by id Software for the AdLib sound card for use in their video games. The default filename extension is also “imf”. The abbreviation stands for “id music file” or “id’s music format”.

ISOBMFF (ISO base media file format): Is a container file format that defines a general structure for files that contain time-based multimedia data such as video and audio.

Over-the-top (OTT): Is a media service offered directly to viewers via the Internet. OTT bypasses cable, broadcast, and satellite television platforms.

MP4: Is a digital multimedia container format most commonly used to store video and audio, but it can also be used to store other data such as subtitles and still images. It allows streaming over the Internet.

MPEG (Moving Pictures Experts Group): Is an alliance of working groups setting standards for media coding (e.g.: compression coding of audio, video, graphics, and genomic data; and transmission and file formats).

MPEG-4: Is a group of international standards for the compression of digital audio and visual data, multimedia systems, and file storage formats.

Multiplexing, also known as Muxing: Is a method by which multiple analog or digital signals are combined into one signal over a shared medium.

Quick Time VR: Is an image file format developed by Apple for QuickTime.