The protagonist, Ember, is a tough, quick-witted and fiery young woman, whose friendship with a

fun, sappy, go-with-the-flow guy named Wade sets up shenanigans with the world they live in – the movie was directed by Peter Sohn (“The Good Dinosaur”), and he had help – among others – by Sanjay Bakshi as Visual Effects Supervisor and TD Markus Kranzler. And with the latter two, we had a sit down!

We had a sit-down with Sanjay Bakshi, who started at Pixar Animation Studios in April 2002 – as a tool developer in the studio’s tools department, where he worked on Finding Nemo, The Incredibles and Cars. Then he worked as a groom lead on Ratatouille, being a digital hairdresser responsible for the hair on humans and the fur on rat characters. Then he was Supervising TD on Monsters University, The Good Dinosaur and Onward. For Elemental, he was the visual effects supervisor. Bakshi is from Saskatchewan, Canada, holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in computer graphics at the University of Saskatchewan.

DP: Elemental looks like there is loads of CG-work in every scene – to get a reference, how big was your team?

Sanjay Bakshi: That changes throughout the production – and how many there were at the peak of production I can‘t say – hundreds across all kinds of department, and (this is just my impression) more then at the usual Pixar movies, because of the scope of the work.

DP: When you first saw the characters and script: What were your preparations, since simulation would be characters (With fire and water as protagonists), the environment would be either drowning or be on fire a lot of the time, and let‘s not even talk about water vapour for people …?

Sanjay Bakshi: Yeah, there is definitely “that” moment at the start – but we knew practically from the start how to change our “regular” pipeline – and that we would have to invest, so that not every shot would be “linear” though the classic pipeline. For example: Not every shot does have to go to an FX artist to work on – because that would be every shot of the movie.

We created technology, that animation artists could do some FX as well – where Ember isn‘t doing a lot besides subtle motion, an animator could do the work, and the fire simulation would happen automatically and behave in a predictable way, so that we would render it out and evaluate, “Oh, this one actually is fine, it can go through to the next department” or, “She does some non-standard stuff there, let‘s give it to an FX artist”. So, we built an automation for the fire simulation and the water simulation that allowed some percentage of the shots to go through without having a lot of FX, while still being made up of FX.

DP: I assume the simulation was done in Houdini?

Sanjay Bakshi: Yeah, Houdini was the backbone for our VFX pipeline. For fluid sims we use a lot of custom work – that‘s the nice thing about Houdini, you can customize so much and built your own tools inside of it.

For the flames, we used “Neural style transfer” – basically machine learning to stylize the flames. Stylized flames because when simulation runs, it‘s a realistic fire. And the Style transfer “organized” the flames, so to speak, into more stylistic patterns, that are simpler and more pleasing for characters – so that was all custom work. And then we developed the “HEXport” – the Houdini Export – when an animator checks in the shot, the simulation automatically runs.

DP: How do you do automatic simulation?

Sanjay Bakshi: Once we got the visual look for Ember, we asked animation to do a bunch of motion tests for us – like walking slowly, walking fast, jumping, sitting down, the generic stuff. Then we ran the simulations for those tests and saw where it behaved, where it didn‘t, and then tuned the parameters of the simulation – and in many instanced, we declared motions a “special case”. For example, when she is moving fast, we dialled down how many tear-offs occur. It was a bunch of hand tuning and a bunch of iteration, to get the parameter space in a place where standard motion would behave nicely.

DP: And with that development for Elemental, do you think of using those style transfers for upcoming movies to save time?

Sanjay Bakshi: In this case, it didn‘t save any time – we‘re still running the simulation and we‘re organizing it, just using these ML algorithms. It actually costs a lot if we use GPUs for it and it increased the amount

of time it takes for us to get our renders back. We didn‘t look at it as an optimization technique, but as a tool to get the look we needed.

But, speaking more broadly, we have other machine learning tools of in our pipeline for denoising and path tracing. So, we‘re always looking for ways that new algorithms and new developments can help us. I‘m sure considering the amount of activity in that space, that there will be other places we‘ll find tedious work to “offload”. There‘s no doubt that generative AI will be used to make something.

DP: Let‘s get to the Elementals itself: How did that work? Are there personal favourites?

Sanjay Bakshi: The fire was really hard to figure out and took a lot of time. And water as well – we spent as much time on Wade (The “Water” protagonist) as on Ember.

We spent a lot of time to on Wade when he was speaking – to create ripples on his face for every kind of mouth shape he made. But those ripples would capture reflections from the environment. And adding to that, we have a lot of bubbles going on. And then on his top of his head, we had a waterfall wave. Yeah, Wade wasn‘t easy.

Initially we were kind of seduced by all of those techniques. And Peter (Sohn) was really loving it because he really wanted Wade to feel water-y. We had all of those things in it, and then we thought we were done and we went to animation and they animated the first scene and they were really concerned.

We couldn‘t see those subtle acting performances we‘re doing, because there‘s so much going on inside of Wade that was detracting from the performance (in terms of the reflections and the bubbles). So even though we had spent as much time on Amber and Wade, we actually had to stop production for a minute and dial back some of those things.

They‘re all still there, but for balance, we had to dial them back. An example: You might notice that the bubbles aren‘t really in the centre Wade‘s face. They‘re more on the sides and in his body. The number of ripples that get produced is really subtle now. And the reflections are really curated to be in specific parts of his body. So, in the end, I think water was more complicated. The other thing is that water is hard to light and looks so different in different lighting environments – it‘s inherently invisible. Fire always looks the same – it‘s emissive, so that was another for our lighting team: Amber always looked great and Wade was very challenging to make look appealing.

On the other end, we really needed it to be “correct” in a way – there is good story reasons for the effects, like when fire characters get close to water characters, the water characters react, they start to boil, they start to steam up. And it‘s trying to show that these elements don‘t get along for physical reasons. Ember doesn‘t fit into this world and she has an effect on them that makes them feel uncomfortable. And that‘s why she wants to stay in fire town and not explore as much. So it was integral to the story that this was done in a simulated way.

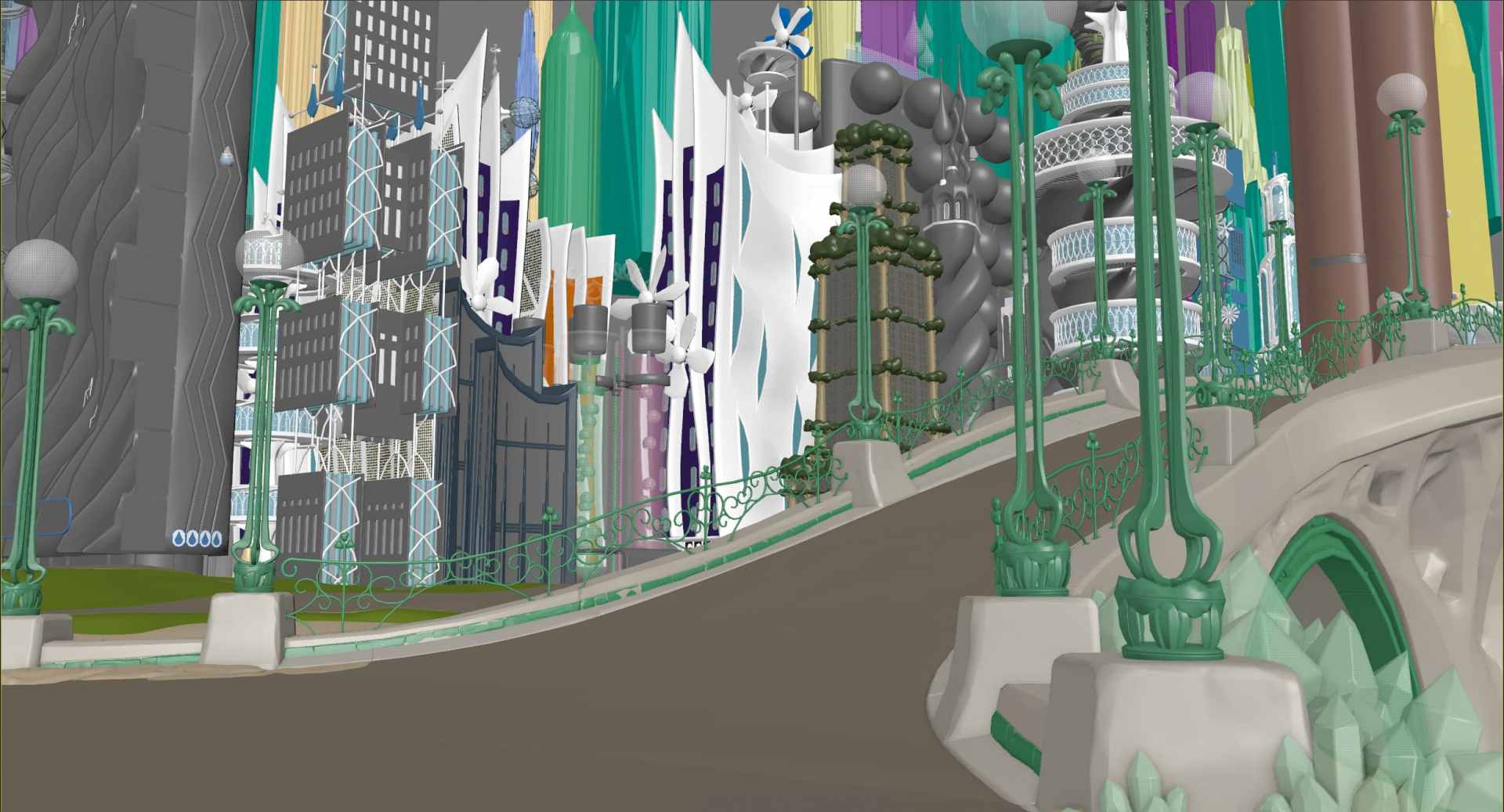

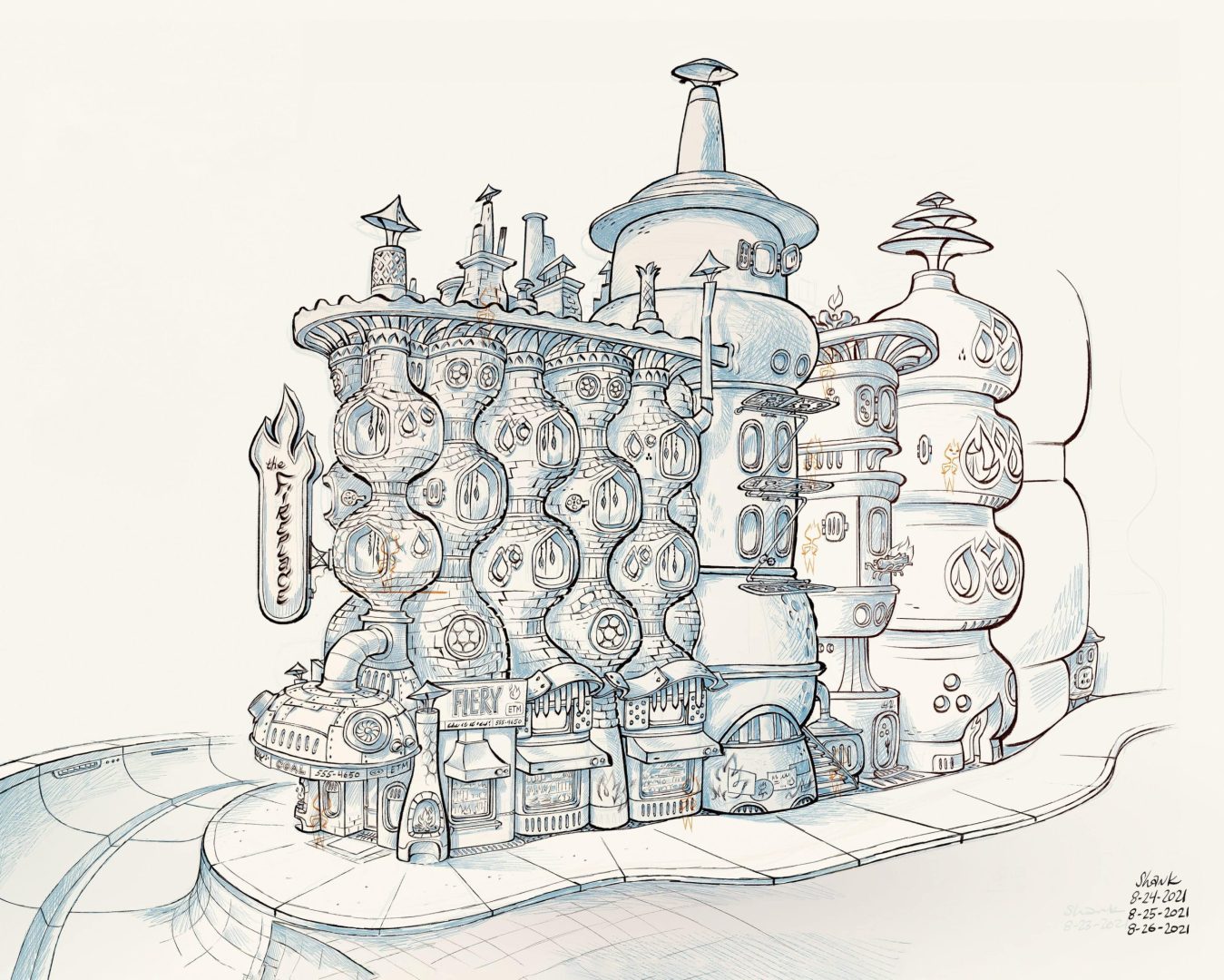

DP: Did you use procedural modelling – like with Zootopia and the CityEngine in Elemental?

Sanjay Bakshi: Yeah, we used procedural building for the artwork of the city, when

we were dialling in the look and feel of the districts, not so much in the final frames.

DP: Like all the previous Pixar Movies, there is stuff happening in the background – I always imagined that gets added by some artists on a Friday afternoon, because it is funny. How do you put in those jokes?

Sanjay Bakshi: Well, that depends – usually those ideas come from all over the team – everyone who thinks they have an idea approaches and asks “Should I put that in?” and that gets curated. But our crowds team has a little bit more liberty. They‘re doing a lot of stuff in the background and sometimes they don‘t ask. Sometimes they‘ll do something just to make their jobs more interesting and will get away with it, and so it‘ll go through and then they‘ll tell us “Oh, we added that thing back there”.

Markus Kranzler ist bei den Pixar Animation Studios in Emeryville bei San Fransisco als Technical Director tätig – nach Stationen bei Trixter, Scanline und MPC ist er beim „Studio mit der Lampe“ gelandet und hat dort unter anderem an „The Good Dinosaur“, Finding Dori, Cars 3, Soul und Coco mitgewirkt – und jetzt an „Elemental“. Übrigens: Unser Favourit der FMX Trailer, Rollin Wild, ist unter seiner Mitarbeit entstanden. Die komplette Liste findet sich auf Linkedin (bit.ly/linkedin_markus) oder Imdb (is.gd/imdb_kranzler)

DP: Hallo Markus! Woran hast du bei Elemental gearbeitet?

Markus Kranzler: Dieses Mal war ich hauptsächlich an den Wasser- und Luftcharakteren beteiligt. Und diesmal war es auch eine sehr enge Zusammenarbeit mit der FX-Abteilung, denn letztendlich sind die Charaktere ja Effekte. Das heißt, ein Teil ihres Wissens, wie sich Volumes und Fluids verhalten, wurde direkt bei uns angewendet. Das war diesmal ein Prozess, wo sehr viele Leute und sehr viele Parteien involviert waren und zusammengearbeitet haben. Das macht es natürlich interessant – wer will schon immer das Gleiche machen?

DP: Die Pipeline wurde also einfach komplett durcheinandergewirbelt?

Markus Kranzler: Im Prinzip ja – natürlich haben wir nun sehr belastbare Pipes, vor allem weil wir auf USD gesetzt haben – aber Optimierungsbedarf gibt es immer, vor allem wenn man mit solchen Datenmengen arbeitet. Die Zeitverzögerung zwischen „Ich habe die Charaktergeometrie“ und „Ich kann es zum Rendern schicken“ war doch recht … groß. ziemlich groß. Und es gab einige Reifen, durch die man springen musste – einige der Tools sind erst entstanden, als wir sie brauchten. Dementsprechend gab es am

Ende der Produktion einige Stellen, an denen man es auch anders hätte machen können. Aber jetzt wissen wir, was wir bei den nächsten Filmen streamlinen können!

DP: Die Charaktere – vor allem Ember, die Feuer-Protagonistin – tragen eine Art Kettenhemd. Da darunter aber alles „Simulation“ ist, wie bekommt man das im Shading sauber hin?

Markus Kranzler: Normalerweise wäre das einfach eine Surface Map gewesen – mit Transparenz und so weiter hätte man das über die Shader „nachgebaut“. Da aber darunter etwas passiert, mussten wir die einzelnen Kettenhemdringe tatsächlich als Geometrie aufbauen und shaden. Also Instanzen in Houdini, in unserem Fall.

DP: Die Szenen sind also extrem klein, übersichtlich und einfach zu handhaben?

Markus Kranzler: (lacht) Ja, natürlich. Bei Elemental waren die generierten Daten sogar ein neuer Größenrekord für Pixar-Produktionen.

DP: Wenn es also um Geometrie und nicht um „Solid Surface“ geht, muss man dann auch für das Shading animieren? Wenn die Figuren atmen, ändert sich ja die Lichtemission?

Markus Kranzler: Da haben wir tatsächlich die Kollegen aus dem Rigging unterstützt und für bestimmte Signale Parameter in das Rigging eingebaut. Diese Signale konnten die Animatoren dann steuern und wir haben im Shading dieses Signal ausgelesen. Bei Ember ist das sehr offensichtlich – sie ändert ihre Farbe, wenn sie wütend wird. Und das ist ein Parameter, der im Rig gesteuert wird, und so bekommen die Animatoren ein visuelles Feedback, und wir haben ein Signal, das wir auslesen, in diesem Fall die Fuel Source der Feuersimulation.

DP: Aber wenn die Feuermenge variabel ist, wie kontrolliert ihr das über die Zeit?

Markus Kranzler: Das kann man sich vorstellen wie Compositing in 3D – also wir haben die Geometrie modelliert und animiert, darauf aufbauend die Simulation in Houdini, aus der wir verschiedene Elemente extrahieren und diese separat behandeln. Also, wie viel Einfluss hat dieser Arm auf die Gesamtmenge der Elemente zum Beispiel. Wobei wir da – dank der Signale im Rig – an manchen Stellen auch schon vorher eingegriffen haben, bevor es ein richtiges Volumen war. Das war notwendig, um zum Beispiel bei Feuer die Outlines, also den roten Rand um die Grenzen des Characters, herauszuarbeiten. Also wirklich so, wie man es aus dem 2D-Compositing kennt: Bestimmte Signale werden in ihren Ebenen verändert.

DP: Und wie habt ihr das gemacht?

Markus Kranzler: Das war ein riesiges Knotennetz in Houdini und hat pro Bild Stunden gedauert. Ach ja, wir haben die Daten für die Charaktere pro Bild generiert, nicht in Sequenzen.

DP: Man sollte meinen, dass das Gebiet ideal für maschinelles Lernen ist …

Markus Kranzler: Ja, punktuell setzen wir das schon ein – den Denoiser in Renderman zum Beispiel. Aber auf der Filmseite wird es immer auf das einzelne Projekt ankommen – die Neural Style Transfers zum Beispiel hängen davon ab, wie stilisiert der einzelne Film ist. Aber bei Pixar ist das nur ein weiteres Tool in der Kiste, das wir benutzen, wenn wir es brauchen – aber im Moment sehe ich keinen Druck, Projekte zu starten, die mehr R&D darauf verwenden.

DP: Und wie viel Zeit hat euch das bei Elemental gespart?

Markus Kranzler: Wir hatten schon einige Iterationen. Der Vorteil war, dass wir eine gewisse Technologie von Disney Research bekommen haben und dementsprechend eine solide Basis hatten, auf der wir experimentieren konnten und mit der wir die Styles entwickelt haben. Bei Elemtal hatten wir natürlich eine große Auswahl, was wir dem Algorithmus als Input geben, aber es hat eine Weile gedauert, bis wir die richtige Balance zwischen stilisiert und realistisch gefunden haben, und wir haben oft mit Pete Sohn zusammengesessen, bis es „richtig“ aussah.