Along with other studios, the best scene of the “Sparas” (The courtyard of the jail) was done by Digital Domain, under the supervision of Aladino Debert. Aladino is a director and Visual Effects Supervisor for Digital Domain in Los Angeles, California, and responsible for the creative direction of projects and supervision of a team of 2D and 3D artists in addition to freelancers. He was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and attended the Pratt Institute for a Computer Graphics Degree. Over the years he worked at Metrolight Studios, VisionArt, Digital Domain (multiple times) and Radium/ReelFX in roles such as CG Generalist, CG Supervisor, Head of CG, Visual Effects Supervisor and eventually Director. His Showreel contains many projects, including (but not limited to) “Ms. Marvel” & Amazon’s “Carnival Row S2” “Lost In Space S2”, “A Series of Unfortunate Events”, STARZ “Black Sails” and “Outlander”, as well as loads of commercial work for Oculus, Nike, Microsoft, Nissan, Dolby and, to round that up, game trailers for Ghost of Tushima, Call of Duty : Black I, Destiny 2 and many more. You can find a full list (including videos) here: aladinodebert.com

DP: Hello Aladino! First of all, my condolences – it must have been no fun working on such a nightmarish creature.

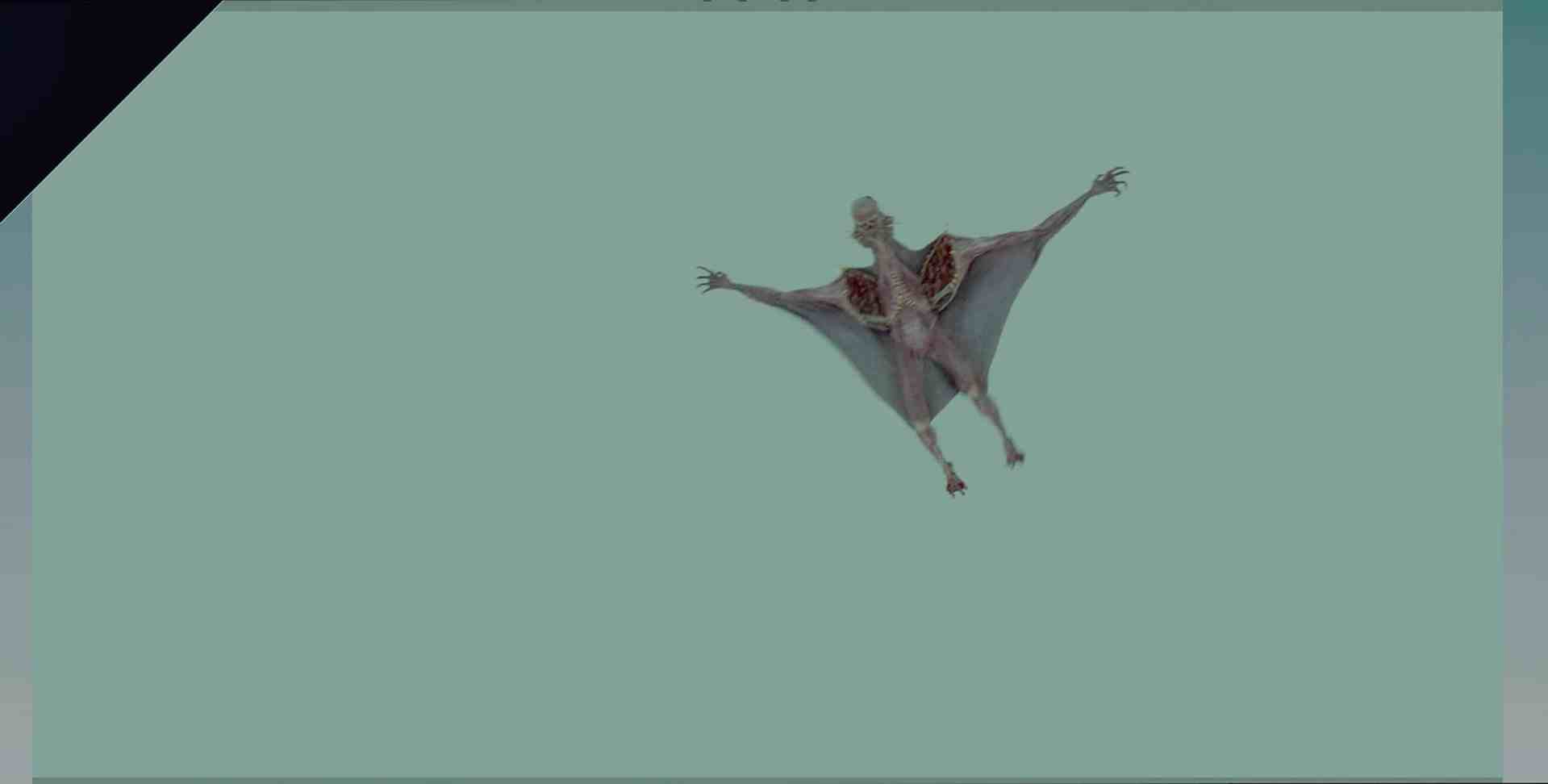

Aladino Debert: Are you kidding? It was absolutely fantastic! Humour aside, working on Sparas was an absolute blast, and I personally fought tooth and nail, pun firmly intended, for the opportunity to be involved in those sequences. Even before we knew if we would secure the project, we took the initiative to create a series of motion and performance tests, which we hoped would serve as a guide for the production team, showcasing the character‘s capabilities and contributing to the overall storytelling. Sparas was a rich and multifaceted character, brimming with complexity and personality. We were incredibly thrilled about the creative possibilities it presented.

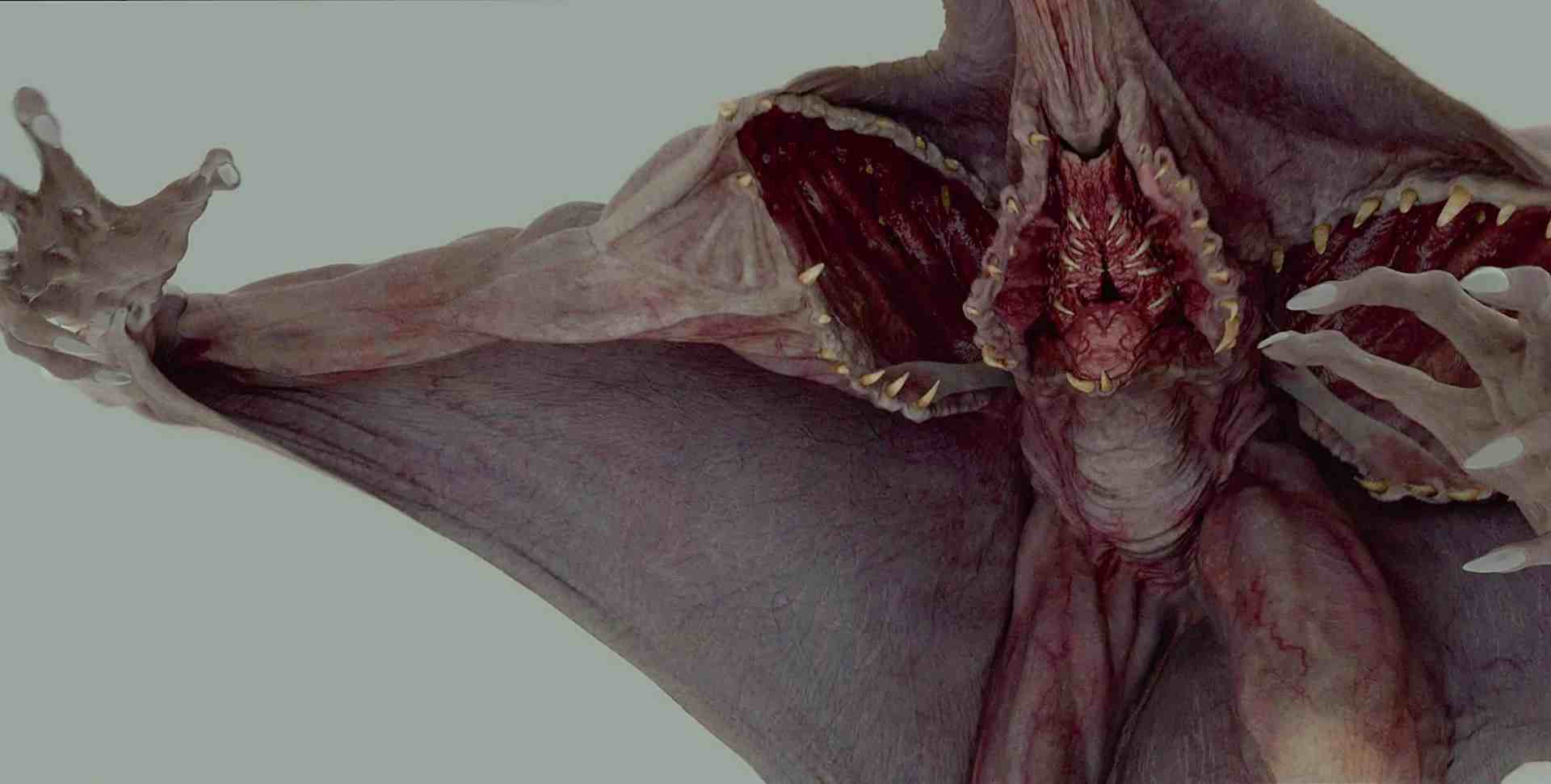

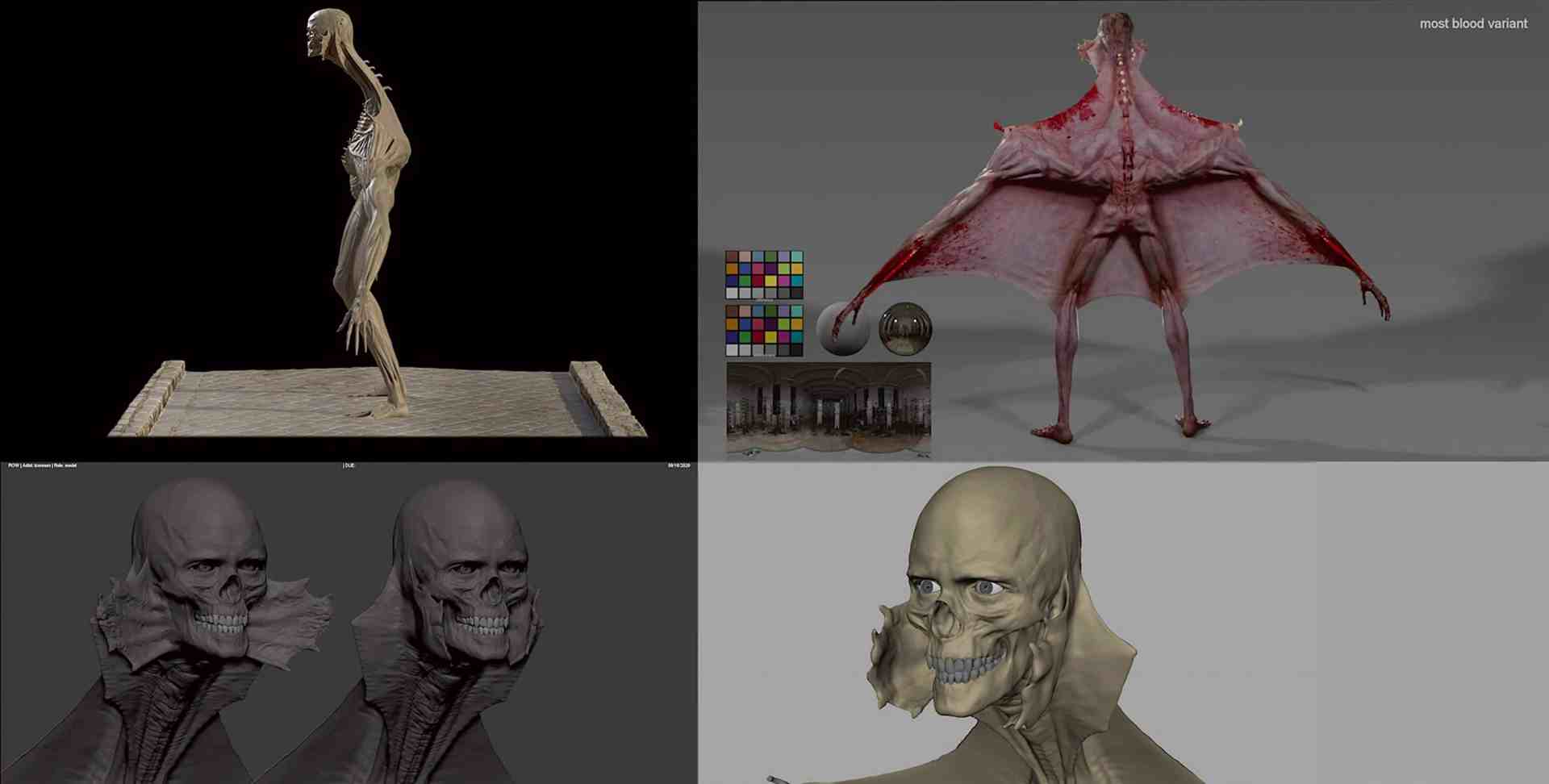

The production team had already started the design process and provided us with a couple of concept frames. However, we had to develop everything else from scratch, including his full anatomy, the way he killed with his forearm blades, which we added, and how he shredded his victims. There was no guidance on his movement or facial expressions, including the impressive flaps that revealed his skeletal face.

We used the initial style frames as a starting point and I collaborated with one of our designers, Chris Nichols, to generate concepts and ideas to present to the clients. Chris produced detailed turntables and renderings, and since he is skilled in both 2D and 3D, we ended up with sculpted models that we could use in our other departments. All told, Sparas, or really “the Sparas” since that’s his species, ended up in about 20-25 shots across a couple of sequences.

DP: Before we get into the monster: Could you describe your normal software pipeline that you used for Carnival Row?

Aladino Debert: Our studio follows a well-established industry pipeline, which aligns with the current practices and the need for flexibility in hiring freelance talent while minimizing training time. We utilize industry-standard software packages such as ZBrush, Modo, and Mari for modelling and texturing. For shot production, we rely on Maya and Houdini for rigging, animation, effect simulation, and lighting, and Nuke for compositing. Additionally, as a long established studio, we have developed a range of custom tools that we regularly employ to enhance our workflow.

DP: With your experience in full CG work like the game trailer for Ghosts of Tsushima, did you approach this as a character or more as a “full environment”?

Aladino Debert: Interesting question. I’ve been in the industry for a long time, and every project I supervise or direct is influenced by my past experiences and, in turn, shapes my approach to future work. I personally am quite agnostic when it comes to tackling each shot, analysing the requirements at hand, and trying to make informed decisions on the most suitable tools and approaches.

And also being flexible when we find roadblocks, so adaptability is key when faced with obstacles along the way. I always say that we are in the business of creating pretty pictures, and the path we take to achieve that can vary. Whether it‘s working on full CGI shots or combining live elements with CGI, my focus is always on delivering the best possible final result.

Now, when it comes to Sparas, characters like him present an additional challenge. Because while they are not real, we strive to imbue them with as much realism as possible, from their appearance and behaviour to seamlessly integrating them into live footage.

DP: How big was the team of “Sparas” wranglers?

Aladino Debert: Due to the specific requirements of Sparas and the limited scope of the work at the time, we had a relatively small team of around 10 artists spanning various departments, including animation, rigging, and tech support. However, had we been able to continue working on the second half of the season, our team would have expanded to accommodate the additional workload. Unfortunately, due to Covid-

related delays, we were unable to continue as planned.

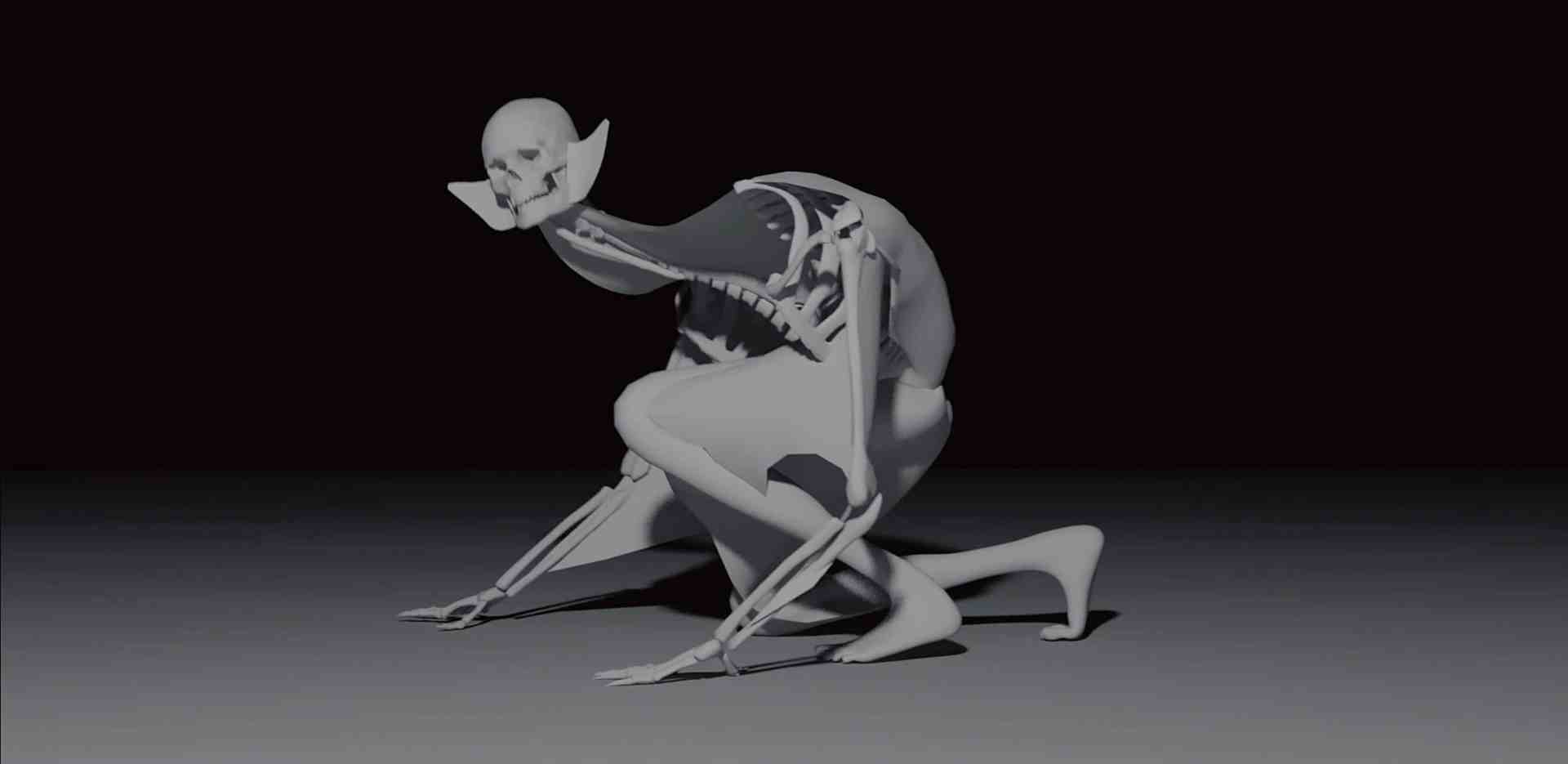

DP: To be honest, I can‘t even begin to imagine the rig inside that thing – tri-point shoulders, secondary and tertiary wings, moving teeth in very unusual places, shockingly wet skin, and a walking anatomy somewhere between a bat and a gorilla: What did the rig look like in software?

Aladino Debert: Right from the beginning, we knew Sparas would be a unique and technically challenging digital character for us. That‘s precisely what made it so appealing to us, and why I pursued the opportunity with such enthusiasm. To answer your question, yeah, the rig was very complex considering the wide range of movements Sparas had to perform, including walking, flying, and engaging in various forms of killing, all while maintaining a sense of realism and coherence in the geometry.

To address these requirements, we developed three separate rigs. The animation rig allowed for the character‘s primary movements, while the CFX rig was responsible for handling dynamic elements such as hair and membranes. Additionally, we had a rig specifically dedicated to simulating the musculature of Sparas.

Given the heavy nature of the final geometry, we also created a low-polygon version of the character within the animation rig. This allowed us to work more efficiently while still preserving the necessary level of detail. Furthermore, for the intricate “Feed me!” segments in Sparas’ midsection, we initially developed an independent rig to ensure its complexity and functionality. Once we successfully tested it on a separate platform, we integrated it into the complete animation rig for seamless integration.

DP: When you got the plates for the first fight in the prison yard: How much “after work” was necessary to adapt it to your preparations?

Aladino Debert: After receiving an initial temporary edit, we began assessing the requirements for achieving the shots. Luckily, the final lock was achieved relatively quickly. However, given the extensive use of stunts, wire work, landing mats, and wire harnesses in those shots, we were fully aware that a significant amount of clean-up work lay ahead. Additionally, we needed to expand the set in all directions. To accomplish this, we utilized a Lidar scan of the set and created a comprehensive digital model of the inner courtyard of the prison, which was employed in nearly every shot of that sequence.

DP: With its transparent skin: How much of the modelling was left to the simulation team?

Aladino Debert: Great question. The principal crew members on this process were Modelling Lead Tristan Connors, Rigging Lead David Lantos and CFX Lead Kim Nielsen, and during the early stages of working on the model we intentionally kept certain aspects vague, as we were uncertain about what could be achieved with the muscle rig. This allowed us the flexibility to revisit and refine those areas later in the process. For example, when it came to Sparas‘ muscular and prominent shoulders, we initially built some definition into the model. However, once the muscle rig was being developed, we handed over that task to the dedicated department, allowing them the freedom to improvise. Through simulation tests and iterations, they ultimately arrived at the final look and feel for Sparas‘ shoulders.

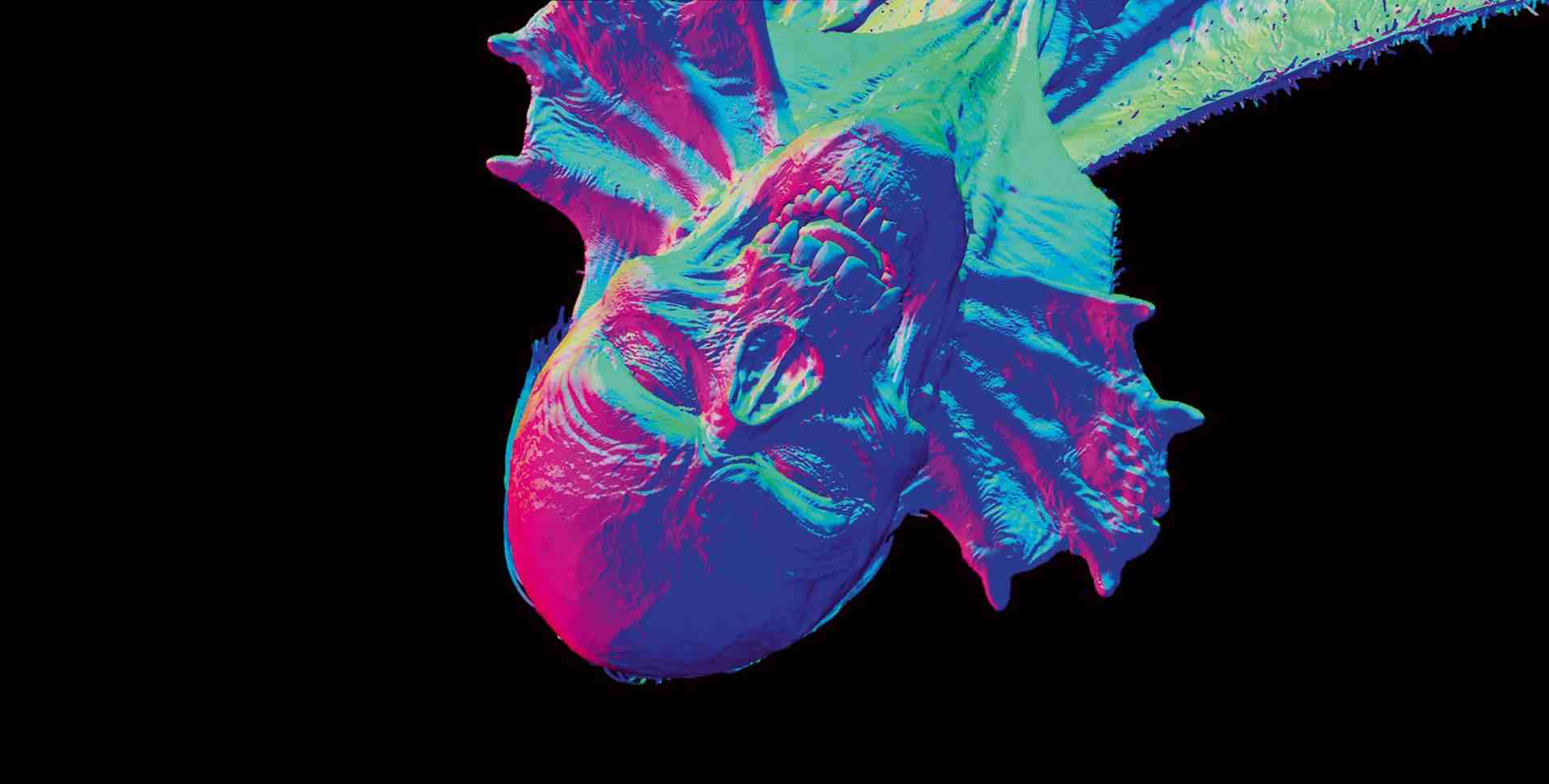

DP: Speaking of simulation and modelling: The muscles underneath the alarmingly damp skin: Could you walk us through your setup for the skeleton and the layers it was made of?

Aladino Debert: The rigging was, as I mentioned before, a set of rigs rather than a single one. The animation rig was relatively straightforward, consisting of low and high poly versions of the geometry, providing precise control for performance purposes. Once the animation was approved, the geometry was passed on to the CFX and muscle simulation departments, both using Houdini but working separately due to their specific requirements.

The CFX team focused on adding Sparas‘ hair and “peach fuzz” throughout his body, plus making sure the membrane of his wings, when folded or flying, behaved realistically. On the other hand, the muscle team took the approved animation and ran it through their muscle rig. This rig, resembling a living anatomy book, incorporated every muscle of Sparas‘ body, allowing for realistic interactions between them. However, it wasn‘t a fool-proof system, and there were instances where animation had to be involved again to address issues that arose with the muscle system. It involved a back and forth process until the desired look and functionality were achieved.

DP: Did you make different versions of the Sparas? A “fast flying one” and an “old one” (which is shown in episode 6, if I remember correctly) and the hero model? Or was it just one?

Aladino Debert: Unfortunately, as I mentioned earlier, our involvement in the later episodes of the show was impacted by the pandemic-related delays. As a result, we only had the opportunity to create one version of Sparas and were not involved in subsequent iterations or appearances of the character.

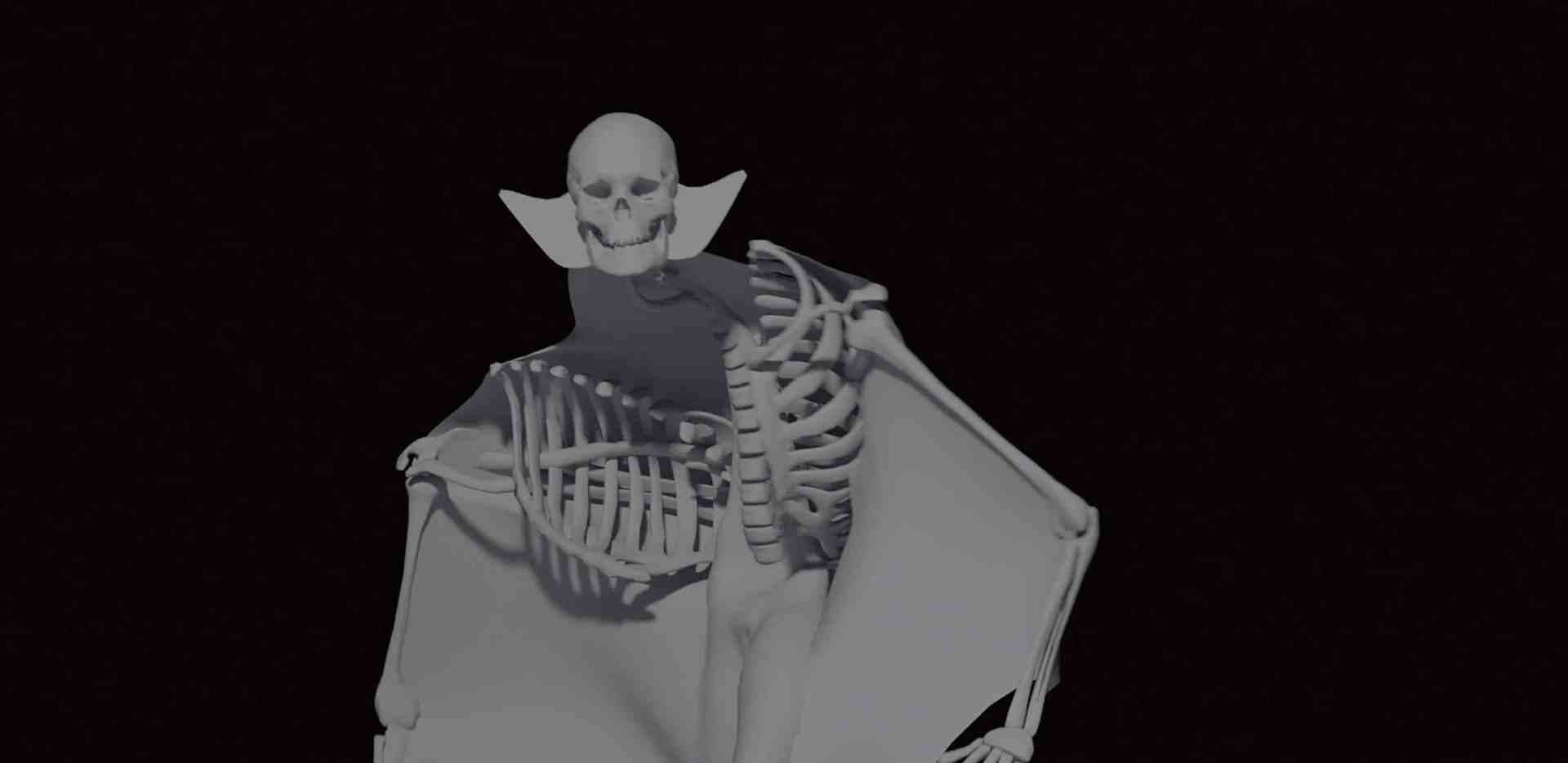

DP: And with the “secondary wings” in the face: How much work was it for the animators to time that?

Aladino Debert: The design process and animation for Sparas‘ face flaps was a complex and iterative one. Initially, the flaps were intended to remain open at all times, but due to Sparas’ role as a changeling who often appears as a human, we decided early on to find a way to close the flaps around his skull. So we used a scan of his face as a basis for the model and when closed, Sparas bore a remarkable resemblance to the actor portraying his human form.

This closure was crucial in enhancing his believability as a human character. Animating a skull to display expressions is challenging, as anyone who’s ever tried to animate one can attest, and the face flaps provided an additional tool to convey emotions effectively. Additionally, it added to the overall personality of the character‘s portrayal.

Creating a performance that both frightened and captivated the audience required numerous iterations and fine-tuning. It was a delicate balance to strike, but we kept at it until we achieved a result that was both terrifying and fascinating. We were thrilled with the outcome and the impact it had on the overall storytelling.

DP: If you had to do it all over again, what would you do differently?

Aladino Debert: Well, every show has its own set of lessons to teach, and I believe in embracing those lessons rather than dwelling on the past. I understand that the process of bringing a show to life is complex and ever-evolving, and not every decision I make will yield the desired outcome. So it‘s important to acknowledge the fluid nature of the creative process and not be too hard on oneself when things don‘t go as planned.

However, I do wish that we had the opportunity to continue working on the remaining episodes of the season. Unfortunately, scheduling conflicts caused by the impact of Covid prevented us from doing so. It‘s disappointing when external circumstances interfere with the creative journey, but it‘s a reality we have to navigate and adapt to.

DP: And what happens with the files now that there won‘t be a Season 3 of Carnival Row?

Aladino Debert: They get archived under the “Tricky Projects” folder [laughing].

DP: What are your upcoming projects where you could use some of the experience from Carnival Row?

Aladino Debert: Like I mentioned before, every show hopefully teaches you lessons you can use on the next adventure. And interestingly, due to those Covid-related delays, I have worked on two shows since finishing Carnival Row. First came work on the first season of “Ms. Marvel” and I have recently completed “Citadel” for Amazon and the Russo Brothers.