Table of Contents Show

LiDAR scanning for VFX and post-production using Leica RTC360 and RealityCapture sounds a bit technical – so let’s ask someone who has been doing exactly that, beyond some demo. Meet Lawren Bancroft-Wilson – if you’ve watched Goosebumps, The Terror or Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency, chances are you’ve seen his work—just not in a way you’d notice.

Senior VFX Supervisor and Producer Lawren Bancroft-Wilson bridges on-set precision with post-production magic, using LiDAR, photogrammetry, and evolving tech to make the impossible feel real. He’s a technologist at heart, constantly exploring how new tools can expand what stories we’re able to tell. That means dragging LiDAR scanners into creepy basements, urban crime scenes, or neon-lit chaos and somehow making it all usable in post.

With over 20 years on set, Lawren knows the joys and pains of capturing real-world locations for CG-heavy shows—and in this conversation, he opens up about LiDAR scanning for VFX and post-production using the Leica RTC360.

DP: Before we jump into the “how”: Can you give us the what and the why?

Lawren Bancroft-Wilson: While I’ve only been directly using LiDAR scanners on my own productions for the past 6–8 years, I’ve been working with LiDAR-derived data since the early 2000s. Even then, it was clear that anything we could receive in post that provided spatial context from set offered a major advantage—both in terms of speed and the quality of the final product.

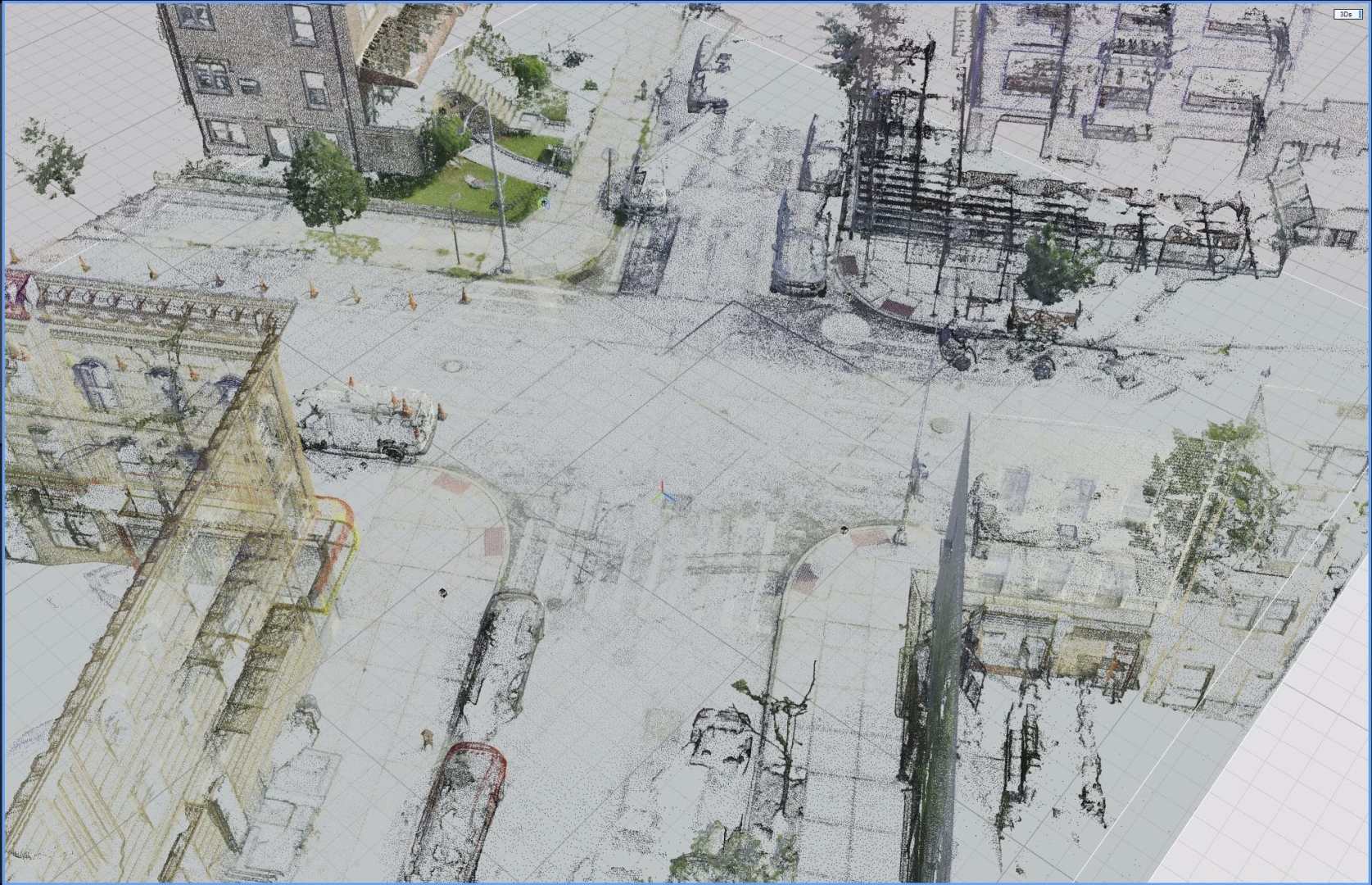

As with all CG work, visual fidelity and believability depend on how well we can match what we build to what was actually photographed. One of the core responsibilities of the VFX team on set is to translate real-world physics into usable digital data so that artists can recreate or extend those environments with precision. LiDAR scanning lets us capture the exact geometry of the world we’re filming in, which becomes foundational for camera tracking, scene layout, and asset building.

In the same way that filming a scene is about capturing and mummifying a moment in time, LiDAR allows us to do the same with the spaces and sets we shoot in. It’s not just about documentation—it’s about freezing the physical reality of a location so it can be carried forward into every part of the VFX pipeline.

DP: So, why did you choose this model of scanner?

Lawren Bancroft-Wilson: When I’m supervising a show, speed and accuracy are the deciding factors in choosing a scanner. The window to get a scan can close in an instant—one moment you have time, and the next the AD is calling for turnover or the crew’s tearing down the set. So we needed something that could deliver high-quality results without slowing anyone down. That’s what drew me to the Leica RTC360. It can capture a full-resolution scan with photos in about 2 minutes and 42 seconds, which makes it realistic to use in the unpredictable rhythm of a real shoot day.

Larger survey-grade units like total stations just don’t make sense for the kind of work we’re doing—unless we’re dealing with expansive topography, they’re overkill.

On the flip side, the BLK360 has had good feedback from colleagues for being compact and affordable, especially with its lower-cost registration software. But for the kinds of environments we’re regularly working in—larger interiors, deep exteriors, or setups that need registration precision—the RTC360’s speed, range, and reliability made it the better fit.

The only real downside is the cost of the registration software. Most VFX workflows shift to other platforms like RealityCapture once registration is done, so investing in the more expensive Leica software ecosystem is something we’ve had to weigh carefully—especially when other scanners come with simpler or cheaper options. But for our needs, the RTC360 has been worth it.

DP: When shooting a scan, do you always go for the biggest resolution?

Lawren Bancroft-Wilson: Not always. We typically go with a medium resolution and more scan positions. That gives us solid coverage without slowing things down too much. Especially on tight schedules, time is everything—and saving even a minute per scan can make the difference between getting the scan or losing the window entirely.

I always capture 360° images, and ideally, DSLR photogrammetry (or gaussian splat data) as well. That combo helps immensely in post for registration, colorizing, and photogrammetry. We concentrate scan density in areas with action or interaction, and gather broader reference when time allows. If a location will evolve across episodes, we make sure our scans overlap so we can align changes later.

Final delivery packages include .e57s, OBJs at various LODs, the original RTC files, HDRIs, photogrammetry, and any relevant art department materials.

DP: Once you have the data: How big is your storage, and how do you transfer it?

Lawren Bancroft-Wilson: Data sizes vary—from a few scans on a small set to 15–20 scans on a larger location. For a typical small set with 5–10 scans, the raw scan data usually ends up around 2 to 3 GB. That scales up quickly across multiple sets or full shooting days, so efficiency and redundancy become essential.

On set, we use the RTC360’s removable USB drives to store the raw scans. At regular intervals, we remove those USBs and back them up to encrypted NVMe SSDs using one of our VFX department laptops. We organize the file structure by episode, date, and location right away to keep everything searchable and production-aware.

From there, the data is transferred to a ZFS RAID system at our location hub, and then synced to the central VFX server at the production office. At any given time, the data exists in three places: the encrypted SSD, the location RAID, and the main VFX server. We never format or clear cards until absolutely necessary.

We deliberately keep our workflow independent of the DIT team. They’ve got their hands full with camera and colour workflows, so our team handles all scanning, backups, and asset management on our own cart.

We also use iPads on set—not only to monitor video feeds and track scan logging when we’re away from video village, but also to operate the RTC360 using Leica Cyclone FIELD 360, which lets us manage scan setups, monitor progress, and validate data capture in real time.

DP: And how much groaning does the DIT have on set?

Lawren Bancroft-Wilson: We try to keep the DIT out of it entirely—and I mean that in the kindest way. We’re great friends with our DITs and camera teams, but their workloads are already maxed out managing camera, colour, and creative requests. Adding another stream of data and logistics to their plate just isn’t fair or practical.

So we manage everything ourselves within the VFX department. That includes LiDAR, HDRIs, photogrammetry, reference photography, witness cameras and all associated backups. Our data wranglers handle all of it using our own gear and streamlined workflows.

In terms of on-set post-processing, we do a bit of early organization and preview—Lightroom for photography QC, and sometimes quick inspections of the RTC360 data using Cyclone FIELD 360 or Artec Studio to look at our Artec Leo scans. But for actual registration, we typically remote into a more powerful machine back at the office where Register 360 and other software is installed. This gives us the option to start reviewing data between wrap and the next call time, without holding up any on-set operations.

DP: How do you connect with the VFX vendors’ pipelines?

Lawren Bancroft-Wilson: We typically deliver unstructured E57s and OBJs at various levels of detail, which tend to be the most broadly supported formats across vendor pipelines—whether they’re using Houdini, Maya, Blender, Unreal, or another tool. Vendors will usually ingest those into their own systems and convert or reprocess as needed, so we focus on delivering clean, organized, and reliable source data.

We don’t enforce a standardized naming convention across vendors—each one will restructure things for their own pipeline anyway. Instead, we focus on keeping our own naming internally consistent. It may not match theirs, but it’s stable and predictable, and that makes it easy to batch convert, remap, or sync across a season. Changing separators or abbreviations mid-show can really break automated tools, so we’re careful to keep that clean.

One thing I’ve found helpful is to always include all expected folders, even if some are empty. If a folder is missing, it creates doubt—did it just not get filled, or did someone forget to include it? Including a full folder structure each time reinforces confidence in the handoff.

We maintain a clear folder structure across the full life cycle of a scan:

- Artec Leo Scans and project Files

- Leica RTC raw scan files and Register 360 project files

- E57 and LGS exports

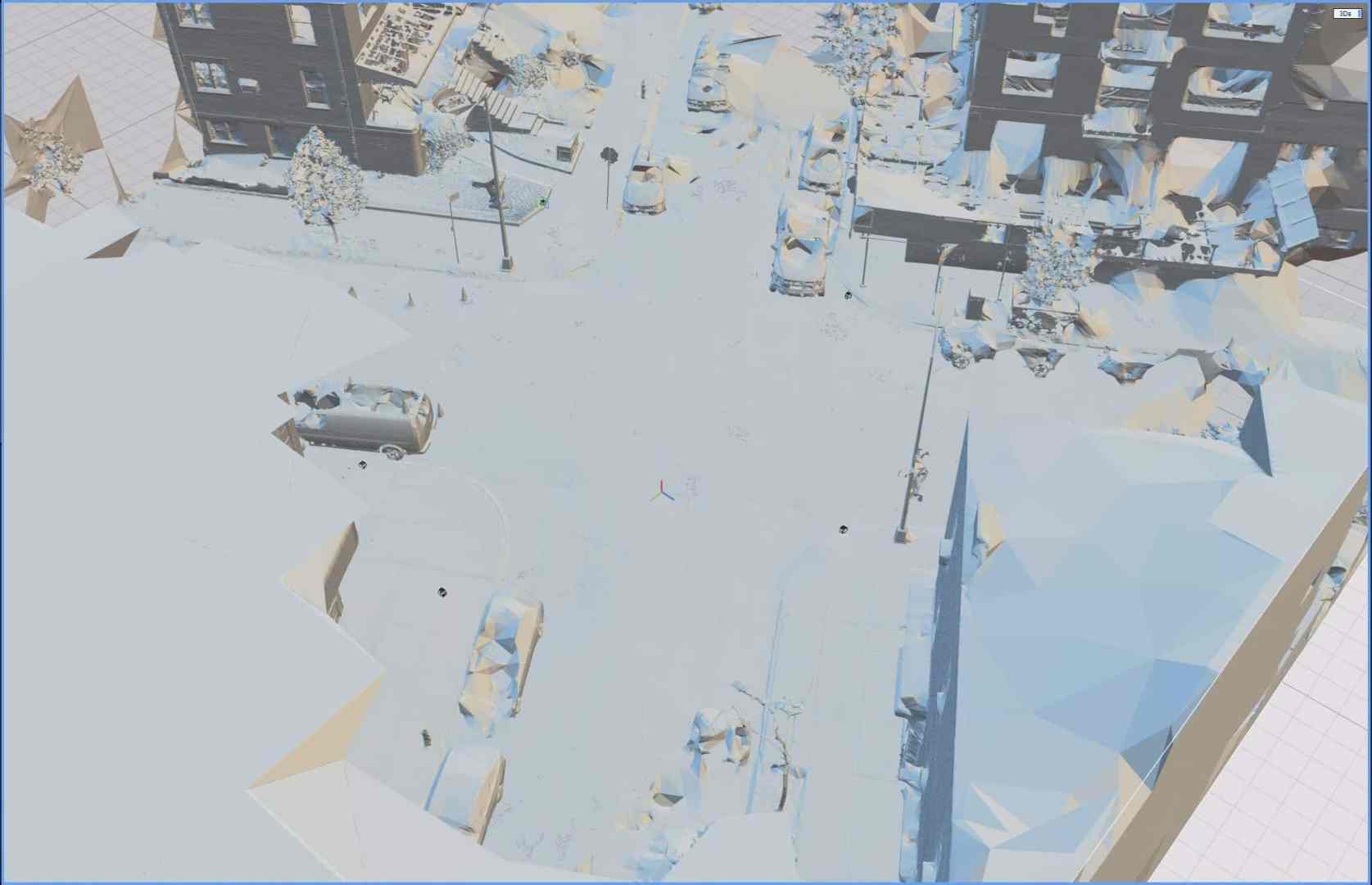

- Epic RealityCapture scene + OBJ LODs

- Photogrammetry and DSLR imagery

- Art Dept Files

- Deliverables folder for vendors, with consolidated materials from all departments

That final vendor-ready folder combines LiDAR OBJs/E57s, HDRIs, photogrammetry, photography, and occasionally artwork or layout drawings. While we track the deeper breakdowns internally, the deliverable is kept as simple and reliable as possible on the outside.

In terms of tools, we use RealityCapture to prep and export geometry from E57s, and sometimes Blender or CloudCompare for QA or visual checks. CloudCompare has memory issues at times, but it’s still handy. Ultimately, most vendors are going to bring everything into Maya first—so as long as the data is clean and lightweight enough to open reliably, that’s the bar we aim to hit.

DP: So, when you get to the set – can you walk us through your Lidar-List?

Lawren Bancroft-Wilson: As overall supervisor, I’m often not the one doing the scans myself—that usually falls to one of our data wranglers or on-set VFX supervisors, depending on the team structure. But we treat scan days like any other shoot day: with prep, coordination, and a whole lot of communication.

Ahead of time, we’ll speak with the 2nd AD to get scanning listed on the call sheet and work with locations to secure access to spaces we might not normally reach. The locations PAs are usually briefed to help us move through the set efficiently. We also coordinate with the DP, gaffer, and key grip to understand the lighting plan, wild wall positions, and whether the set will be scanned in one configuration or several.

We try not to scan too early in the day. Often the set is still being finalized, and it’s tempting to get in there quickly, but you risk scanning a version of the set that’s going to be tweaked, blocked differently, or partially stripped out before first shot. Instead, we usually wait until a key setup is finished or during natural breaks like turnarounds, costume changes, or lunch.

Blocking is also a big factor. You may discover that what seemed like background is now in direct focus, so we try to wait until the first few takes to confirm where the action is concentrated. That informs how dense the scan coverage needs to be in different zones.

Lunch is great—if the crew goes and the lights can stay up, we can sometimes get a full scan without disrupting the schedule. But any plan to scan during lunch means speaking well ahead of time with the gaffer and key grip to make sure, if any of their team is needed to stay behind, they’re able to break early. VFX never wants to stand in the way of anyone and their well-deserved lunch.

We don’t typically place special references into the environment—at least not for LiDAR. The scanner captures what’s there, and on most sets, there’s enough unique geometry and dressing to orient the cloud. We’ll use grey and chrome balls for lighting reference, but those are captured separately and are not tied directly to the LiDAR itself.

I’ve been lucky to work with directors and DPs who really get it—who understand the value of what we’re capturing. When they do, they’re often the ones calling for quiet or holding crew so we can get the data we need. I’ve even had actors step in to help explain what’s going on when someone doesn’t realize why we’re taking a moment to scan. Not everyone knows what the LiDAR is for, but when the leadership does, it sets the tone for the whole crew.

We’re all there to create the best final product, and we’re all specialists in our own fields—knowing what we need, but still wanting to get home to our families and friends after a long day of shooting. So being respectful of what other departments need, and showing how VFX can support them too, always pays back in multiples when it’s our turn to ask for help or time.

DP: And when there is a time-constraint, because of a not-closed set, or some public access or a tsunami wave coming over the horizon: What is the “minimum viable scan” you go for?

Lawren Bancroft-Wilson: We run into this kind of situation all the time—tight windows, limited access, and not nearly enough time to get everything we’d ideally want. So when it comes down to it, we focus on scanning the areas of primary action and key camera coverage. That gives the vendors something grounded to work from and avoids a complete reliance on eyeballed matchmoves.

We also try to make sure the scans connect—if we can capture just enough locations to link the space together, even loosely, we can usually get it to register properly in post. If we know there’s going to be a return visit or the location changes over time, we’ll prioritize overlap zones to help line things up across scans.

At the same time, we’re often working in parallel—while one person handles LiDAR, another might be grabbing quick photogrammetry, or even just walking the space with an iPhone for video reference. It’s not glamorous, but that kind of continuous visual record can be a lifesaver later.

For lighting, we’ll still try to get a proper bracketed HDRI with the DSLR, but if time’s tight, we may also shoot a fast one with a 360° camera—it’s not perfect, but it’s better than nothing. The goal is to capture as much useful context as possible without slowing down the production.

And while public access or crowds aren’t usually a huge issue for us—our locations team does a great job locking things down—there’s rarely a scan where we get everything we want. So we aim for strategic coverage, get what we can, and over-communicate later so everyone knows exactly what they’re working with.

DP: When VFX-supervising during the shot, do you use additional tracking markers?

Lawren Bancroft-Wilson: To be honest, we haven’t typically used dedicated tracking markers like you’d see on larger LiDAR setups. But we’re always contending with glass and reflective surfaces. In those cases, aside from giving them a hit of AESUB Blue vanishing spray, we’ll sometimes use little squares of green camera tape across reflective areas—especially glass—to help define geometry that might otherwise go missing in the scan. That said, the RTC360 handles reflective surfaces like cars particularly well. Combining a scan with photogrammetry and Gaussian Splatting you can fill out a scan quite well.

DP: Let’s talk about the actual machine: With TSA and other agencies running amok, can you take it on a plane? And what is in your carry-on for travelling with the RTC?

Lawren Bancroft-Wilson: I’ve flown with the RTC360 a few times now, mostly between Canada and the U.S., and surprisingly, it’s been pretty smooth. TSA agents are usually curious, but not alarmed. I find it helps to explain that it’s basically a more advanced version of the LiDAR tech already built into many iPhones. That usually clicks for them, and once they hear it’s for film work, curiosity often replaces suspicion.

That said, I try to carry the scanner on with me whenever possible. I’d rather have it overhead than risk it getting bounced around or stuck in customs. The tripod usually goes into checked baggage, along with other less sensitive gear. I’ve had issues in the past with shipping, especially internationally—mismatched waybills or delays through customs clearance—so now I try to keep it on my person if I can.

I use a Leica GST80 Tripod for the RTC360, especially when scanning in windy or exposed locations like Tofino or coastal environments. Stability is key for both the gear and the data.

For storage and transfer, we travel with a mix of encrypted SSDs and a local ZFS RAID system that stays with us on location. We also carry an iPad Pro, which we use to operate the scanner via Leica Cyclone FIELD 360, and a MacBook, which we use for backups, QC, and general scan management.

And yes, we travel with AESUB Blue vanishing spray—especially useful for scanning props with reflective surfaces like stainless steel, glass, or painted metals. It’s not cheap, but it’s one of those tools you’re glad to have when you need it.

DP: When you got everything set up: How long does the actual scanning take in your workflow? And how much effort and concentration does it take? Could an intern handle it, after the first pass?

Lawren Bancroft-Wilson: The scanner itself isn’t hard to use. The learning curve on the RTC360 is pretty manageable—most people on our team can pick it up quickly and run a basic scan. But what separates someone who can operate the scanner from someone who can really integrate it into a shoot day is the ability to read the flow of set, time it right, and communicate confidently with other departments.

That’s the real skill—not pushing the buttons, but understanding when it’s okay to hold the floor for two more minutes and how to ask for that without creating friction. It’s knowing how to stand your ground without slowing the day or rubbing anyone the wrong way.

We’ve had a mix of people handling scans on different shows—sometimes me, sometimes the on-set VFX supe, and often our data wranglers, who have been absolutely outstanding. On my last show, they had a great rapport with the crew in New York. Everyone respected the work they were doing because it was fast, precise, and never felt like a time suck. They were always present, watching the cues, ready to move when the window opened, and tracking what was done so we didn’t miss anything.

I think it’s important that everyone on the VFX team understands how to scan. Not just for redundancy, but because it builds appreciation for the challenges that come with it—and that understanding feeds back into better decisions in prep, shoot, and post.

DP: Earlier models had problems with directed IR Light sources – is that still a problem?

Lawren Bancroft-Wilson: To be honest I haven’t come across any IR light issues.

DP: Imagine a perfect world, and you are shooting with the best directors, DoPs and an unlimited budget: What would your wishlist for the perfectly Lidar-Scanning compatible set be?

Lawren Bancroft-Wilson: I’d love to scan more natural environments—beaches especially. If you gave me a week to scan a beach, I’d gladly do several tech scouts to figure out the exact time of day and conditions. Ideally, I could become the go-to choice for remote beach scanning around the world.

Sets are fun, too—but the biggest luxury would honestly just be time and space. A perfect LiDAR-compatible set isn’t necessarily about what’s built—it’s about having the freedom to access it without having to dodge crew, lighting tweaks, or production pushing forward. Give me a few hours alone with a space, and I can get you something great. That’s rarely the case in the real world, though.

I think a dream setup would be a hero location that we’re returning to multiple times throughout a show, where we’re given the chance to scan it thoroughly once, without pressure. That gives us a full base model we can build on, align to, and update with smaller detail scans as the production progresses.

So really, any set where everyone’s comfortable, there’s enough room to work, and we’re not rushed to get in and out—which is to say, no set ever.

DP: And when we look into your projects in 2035: What would you expect in features of your next-next scanner?

Lawren Bancroft-Wilson: One of my big hopes is that future LiDAR systems become even more integrated—capturing not just geometry, but lighting and color data in a way that’s accurate and production-ready, straight out of the scanner. The dream is to walk onto a location, scan it, and come back with a photorealistic digital twin that’s ready to drop into a techvis or layout workflow with minimal cleanup.

I’d love to see more computational photography integration too—leveraging the advances we’ve seen in phone cameras and neural imaging to better capture color fidelity, material surfaces, and depth in one cohesive package. Better built-in cameras on the scanner itself would help, but ideally the whole imaging and geometry pipeline gets smarter and faster. And then there’s usability. I’d want something lighter, faster, more power-efficient, and more accessible—both in price and ease of use.

But the real holy grail is how we use the data once we have it. I’d love to use LiDAR to start virtually scouting, blocking, and planning—using the captured space as a living reference for storyboarding and camera planning, maybe even from within augmented reality or wearable displays. The faster we can get from reality capture to creative application, the better.

Just recently, I attended a showcase by Sony and Pixomondo near Vancouver, BC, where they demoed their Akira system—a cutting-edge virtual production setup with precise, repeatable dolly control and an advanced motion base for vehicles, all set against beautiful LED walls running high-fidelity Unreal environments. But what really stood out came at the end of the presentation, when they previewed work involving Gaussian Splatting—capturing environments with traditional cameras and generating point clouds in just a few hours that could be pulled into Unreal Engine for techvis, previs, or even to display on an LED wall.

The potential there is huge. Being able to capture a real-world space quickly and have it usable almost immediately across multiple production tools is exactly the kind of leap we need. I think the future lies in combining high-fidelity LiDAR like the RTC360 with real-time photogrammetry or Gaussian Splatting, giving us a fast, detailed, and usable digital version of a location—without a long environment build and approval cycle. And once you factor in emerging AI tools for re-texturing, relighting, or even expanding those worlds, it feels like we’re right on the edge of something transformative for how we digitize and interact with real environments.

1 comment

Comments are closed.