Table of Contents Show

Gene Roddenberry’s team shot the first pilot episode for “Star Trek” back in 1964. The Anderson Company, which was part of Desilu, the production company, was responsible for the visual and optical effects for both pilot episodes as well as the following episodes. However, the Anderson Company was already hopelessly overwhelmed when editing the effects for the first regularly filmed episode, “The Corbomite Maneuver”.

At the time, nobody was prepared for the mass of visual effects that a weekly science fiction series would entail. Before Star Trek there was “Lost in Space” and “Buck Rogers”, but here you were surprised if you didn’t see the strings on which a model was hanging. The quality standards for Star Trek were different.

Star Trek was also the first science fiction series to be shot in colour, which significantly increased the effort and problems involved. What’s more, the cinema was just showing what science fiction could look like: “The Time Machine” from 1960 or “Fantastic Voyage” from 1966, which won an Oscar for its groundbreaking effects, naturally also increased the pressure of expectation on the makers of Star Trek.

In desperation, producers Gene Roddenberry and Robert Justman hired Eddie Milkis, who had previously worked as an editor. He quickly realised that the sheer number of effects shots, or opticals as they were called at the time, could not be managed by one effects house, but rather by all the effects houses that existed in Hollywood at the time. And so Milkis became probably the first post-production supervisor in our industry, even though this job title didn’t even exist back then. He was listed in the credits as a production assistant.

The practice that is common in our industry today of distributing shots to several service providers and coordinating them in terms of content, design and economics by a studio-side supervisor thus took place for the first time on “Star Trek”. But visual effects not only created problems, they also solved some of them: Beaming the crew around Kirk and Spock was not only a futuristic means of transport, it also solved the problem of having to land the Enterprise or one of its shuttles in every episode – an effect that would have been much more costly than a dissolve between the take with the actors and a corresponding cleanplate.

The actual transporter effect was applied to this dissolve with the help of an Oxberry printer – moving aluminium shavings, illuminated by a strong light, transported our heroes to alien worlds. Incidentally, the fact that the Enterprise ended up with a shuttle at all was thanks to one of the first and probably most creative merchandise deals of all time. The company AMT Ertl was granted the licence to sell Star Trek model kits. In return, AMT promised to build a full-size model of the shuttle for filming – another way of keeping the ever-exploding budget down.

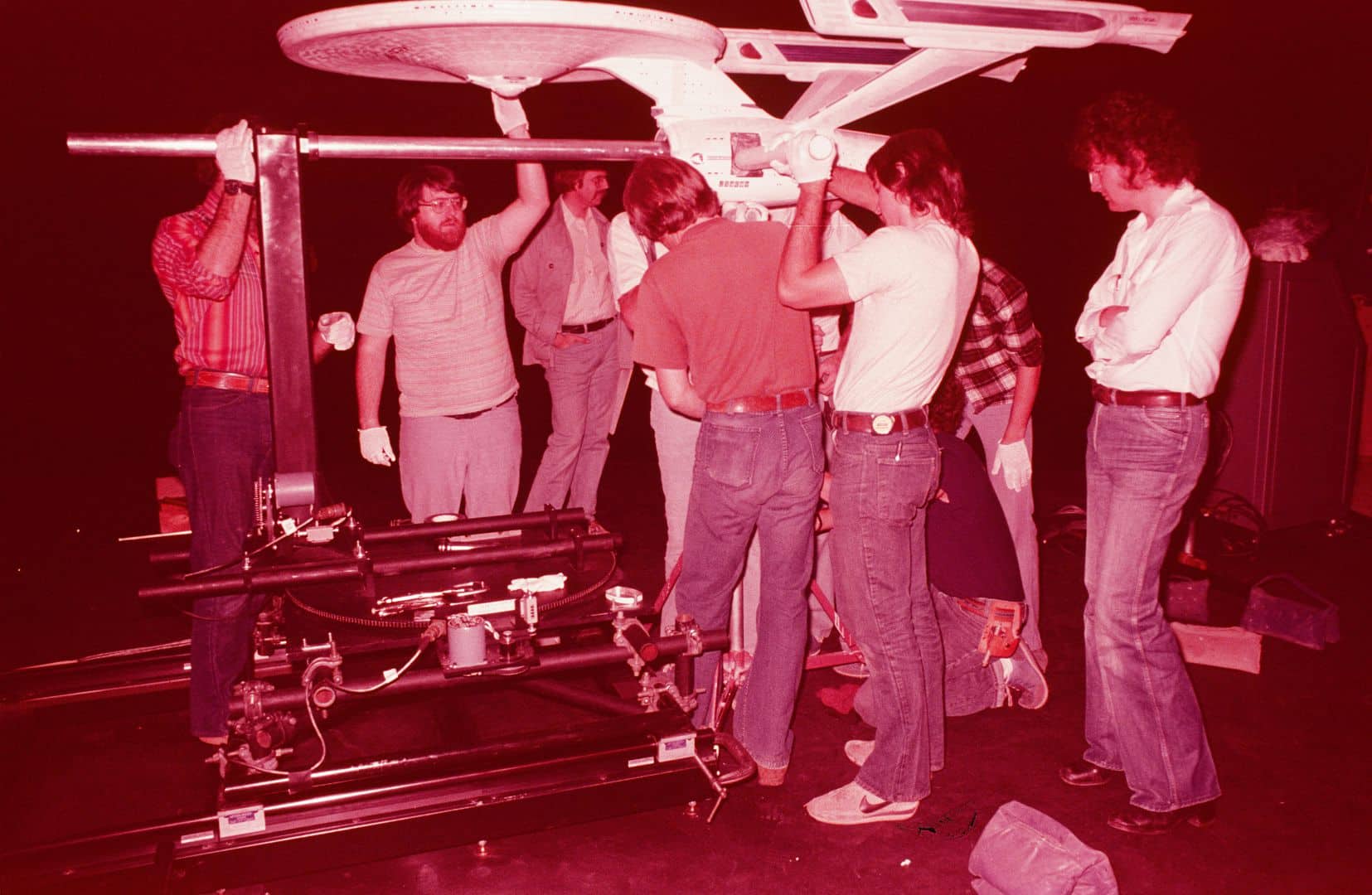

The Enterprise itself was built as a model in three sizes: A twelve centimetre model, one ninety centimetres long and a detailed version four and a half metres long. The materials used were balsa wood and plastic, which didn’t exactly make filming any easier, but modern materials such as fibreglass were still rather experimental at the time. There was also little motion control technology available, which meant that both the movements of the Enterprise and the lighting were limited. The shots of the Enterprise were filmed in black and white and then recoloured on the Oxberry printer and punched in front of the appropriate planet of the week.

This process of re-colouring also explains why the Enterprise often had a different colour cast in different episodes. It was particularly noticeable when the producers used another cost-cutting measure: the recycling of optical effects. Especially exterior shots of the Enterprise, when it was not shown in orbit around the planet of the respective episode, were often shown several times. For example, the Enterprise could fly around a planet with a reddish tinge, only to chase the Klingons a few minutes later in the most beautiful blue.

Especially in the third season, when the budget was radically slashed, this can be observed very often. But every trick in the book was used to transport viewers into the twenty-third century. The beams from the phasers were painted frame by frame for both the live action shots and the model shots of the Enterprise – whether the phaser was red, green or blue often depended in the end on which effects house was responsible for the respective shot.

Today, the effects may seem antiquated or even ridiculous in some cases, but you should really bear in mind that “Star Trek” was the first series to work with effects on this scale. Whereas other series had perhaps two or three visual effects shots per episode, one episode of “Star Trek” easily had twenty such shots on the television screen.

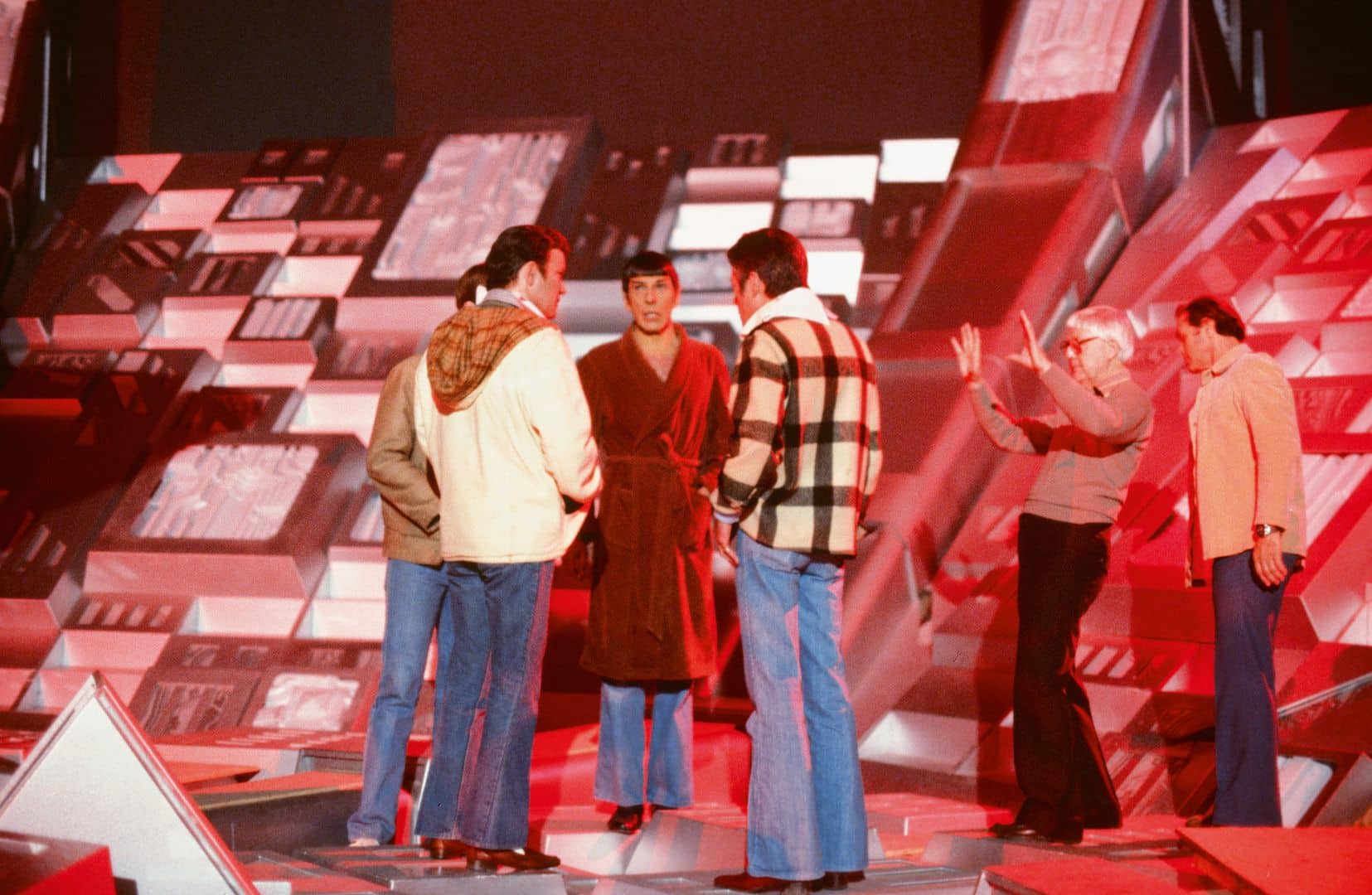

The Motion Picture was a test of many nerves.

Star Trek’s path to the cinema led through many stages of “development hell”. Several projects were considered and then cancelled until Paramount Pictures, now the rights holder of Star Trek after the acquisition of Desilu Studios, decided to send the Enterprise on a second five-year mission. Star Trek – Phase II was to become the cornerstone of a new television channel. Sets were built, scripts written, test recordings made – and then everything changed. After the success of “Star Wars” and “Close Encounters of the Third Kind”, Paramount now saw Star Trek as an opportunity to bring something similar to the big screen.

The script for the pilot episode of “Phase II” was thus developed into a two-hour opus and Robert Wise, known for “The Sound of Music”, “The Day the Earth stood still” and “The Andromeda Strain”, was hired as the director. Without going into too much detail about the drama behind the scenes, it is important to know that the script was constantly changed.

Screenwriter Harold Livingston was in a constant battle with Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry. William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy insisted on changes on their part and, to add to the pressure, Paramount had the film booked for a fixed date in cinemas. On the seventh of December 1979, “Star Trek – The Motion Picture” had to flicker across the screen or the studio would be heavily sued.

helping hands to bring the Enterprise to the big screen.

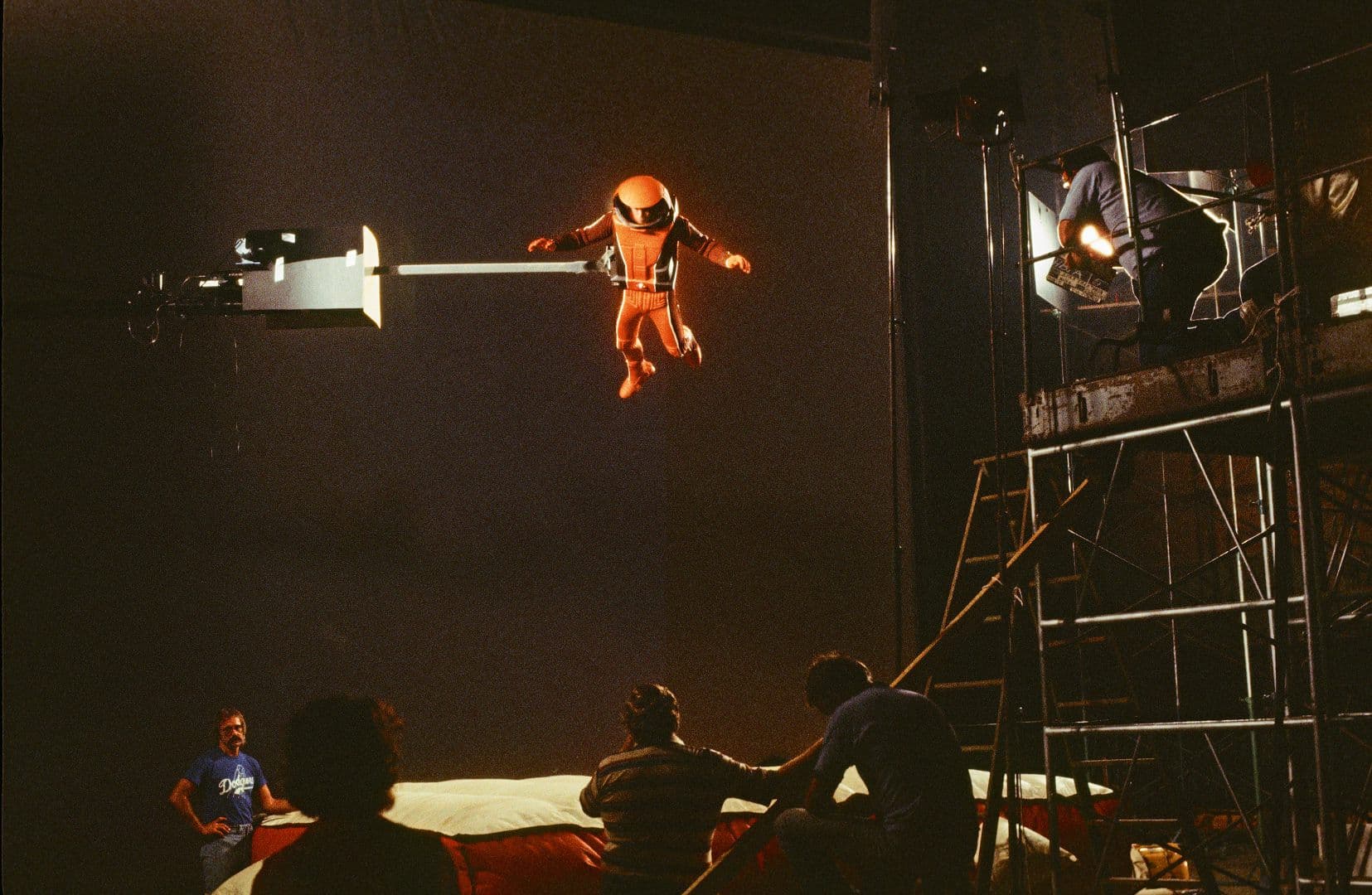

Robert Abel and Associates was chosen as the effects house at the time. This company had made a name for itself in Hollywood with groundbreaking commercials for the time – but also with notorious delays and exploding budgets. Concerned about this situation, Paramount brought Douglas Trumbull onto the project as a consultant in August 1978. Trumbull had already been responsible for the visual effects on Stanley Kubrick’s “2001 – A Space Odyssey” and was working at the time for the Paramount company “Magicam”.

When it became clear that Abel and Associates would not be able to meet the deadline, which was so critical for Paramount, Trumbull took over the visual effects and was thus given carte blanche on the project in many respects, also with regard to the finances. Meeting the release date was so important to those responsible at Paramount that the budget was increased several times and ended up at 44 million US dollars – originally calculated at 15 million.

But even Douglas Trumbull could not cope with the mass of visual effects on his own, which is why John Dykstra’s Apogee Studios also came into play. While today it is common practice for several companies to work on the effects of a single film, this cooperation caused additional logistical problems at the time. While Trumbull’s Entertainment Effects Groups Pipeline relied entirely on 65 mm film, Apogee worked with Vistavision. All live action scenes were shot on anamorphic 35mm.

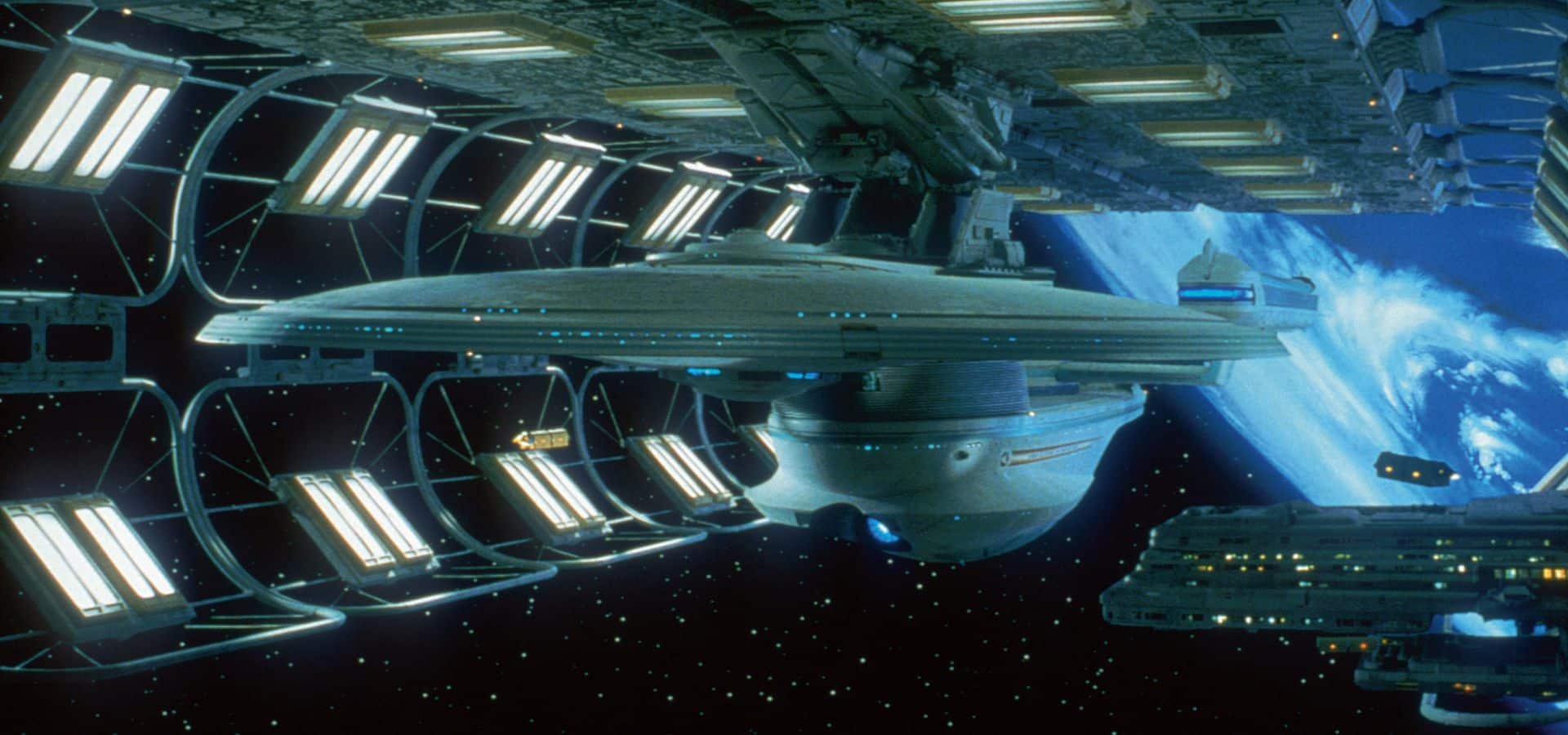

The film contains some beautiful shots and groundbreaking effects: Marvellous flights through the giant alien probe called “V’ger”, all an evolution of the slit scan process from “2001”, the wormhole effect, and of course the almost nine-minute flight around the completely refurbished U.S.S. Enterprise – to this day a breathtaking sequence that fans like to call “ship porn”. Never before and rarely since has the Enterprise looked so good. And yet, to this day, one still has the impression that the film comes across as long-winded, elegiac and bloated. Here, too, the fans have found a fitting name: “Star Trek – The Motionless Picture”.

There is a reason for these lengths – in addition to weaknesses in the script. The effects were largely completed so late that they were used in full length in the editing process – there was simply no time for a proper editorial process. In the end, it was so tight that director Robert Wise personally took the still wet film reel of the fifth act to the premiere.

Nevertheless, the circumstances surrounding “Star Trek – The Motion Picture” were nothing less than a perfect storm for the fledging VFX industry. The deadline was set in stone, the film had to be finished. If you study the credits of this first cinema adventure carefully, you will realise how many remarkable careers began here.

The Genesis trilogy

The budget, which had exploded from the original fifteen to forty-four million dollars, was still a very sour pill for Paramount to swallow. Nevertheless, they wanted to send the Enterprise on another journey, perhaps this time a little more profitably than with the first film. Paramount turned to Harve Bennett, then a producer in the TV department of Paramount Pictures. When asked if he could make a Star Trek film for less than 44 million dollars, he replied that he could make three of these films for the budget. He was to keep his word: “Star Trek II – The Wrath of Khan”, with a budget of 11 million dollars, was to become one of the most successful films in the franchise.

Industrial Light and Magic, although still busy with “Return of the Jedi”, opened its doors to other clients at this time, and one of the first was Paramount Pictures for the Enterprise’s latest adventure. Some shots could be recycled from the first film – just like they did on the TV series. When the Enterprise leaves Earth, it’s a radically edited version of the dry dock sequence from “The Motion Picture”, and the simulated battle with the Klingons has also been seen before.

Nevertheless, the film has a completely contrasting look, much denser and more compressed than the opulent first film. This is also reflected in the techniques used. For example, the Mutara nebula, in which Admiral Kirk duels with the eponymous Khan at the end, was not created using slit scan technology, but in a water tank. Different coloured liquids with different viscosities were mixed and filmed at a high frame rate. The Enterprise in battle with the U.S.S. Reliant were then visually superimposed over this nebula. “Star Trek” probably benefited greatly from the experience ILM had gained with “Star Wars”, especially with the use of motion control and the impressive orgy of destruction at the end of the film.

The masterminds at ILM used another clever trick in the two battle sequences between the Enterprise and the Reliant: In order to have a believable scale during the explosions, especially of flames, details that were destroyed were built as a partial model on a larger scale. This meant that a warp nacelle could explode without looking as if it had been hit by a gigantic Bunsen burner.

In another respect, however, “The Wrath of Khan” broke completely new ground and has a unique effect sequence that can hardly be underestimated for our industry as a whole: the genesis sequence, in which the creation of a planet from the impact of a torpedo on a dead celestial body to its transformation into a living planet with mountains, valleys, meadows and lakes is shown in a one-shot, is the first completely computer-generated sequence to be used in a cinema film. It was created before Lucasfilm Computer Graphics Division. This division was renamed Pixar shortly afterwards.

Two years later, “Star Trek III – The Search for Spock” followed. Ince again the effects where made by ILM, and the aforementioned Genesis sequence was once again recycled. The film is quite solid in terms of the effects, but suffers a little from the conditions in the TV department. The scenes on the Genesis planet unfortunately show that they were filmed in the studio and not in Hawaii, as cinematographer Charles Correll wanted. The destruction of the iconic Enterprise, however, is still an eye-catcher even after almost forty years and has definitely aged well.

“Star Trek IV – The Voyage Home” is not really a film that makes you think primarily of groundbreaking visual effects,as most of the film is set in the 1980’s San Francisco. What is remarkable, however, is the journey through time that Kirk and his crew manage by warping around our sun. During this flight, we see a somewhat etheral scene in which the CGI heads of our heroes morph into one another. Back then, the actors were scanned in a construction that seems crude today and which, in retrospect, can be seen as the great-grandfather of today’s light stages. Quite remarkable for the year 1986.

Never change a winning team

“Star Trek V – The final Frontier” was not only to be William Shatner’s directorial debut, but also to continue the success of “The Voyage Home”. However, competition in the 1989 cinema summer was fierce and ILM was already busy with films such as “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” and “Ghostbusters II”. Worried that ILM would only be able to let the “C-Team” work on Star Trek V, the decision was made in favour of the effects house Assoicates and Ferren from the east coast of the USA.

As with “The Motion Picture”, they opted for an effects house from the advertising sector and overlooked the fact that this company did not necessarily have the right pipeline to handle the effects for a science fiction motion picture. The distance between Hollywood and Long Island, New York caused additional problems in the approval processes, as did the lack of experience and the obvious disinterest in the effects of director William Shatner.

Many of the effects in the “Galactic Barrier” appear overlit, the Enterprise is poorly integrated or not integrated at all and the overall proportions in the film don’t seem appropriate. The approach of Associates and Ferren was also fundamentally different to that of ILM. While ILM had already refined the bluescreen technique for itself at the time, Bran Ferren was absolutely unwilling to work in this way.

To make matters worse, between “The Voyage Home” and “The Final Frontier”, the model of the Enterprise had been loaned out to film an attraction at Universal Studios. The effects company responsible had sprayed the model with a matt finish, presumably to prevent blue screen spill. The elaborate mother-of-pearl effect that the Enterprise had been given for “The Motion Picture” had to be reapplied over a period of several weeks.

Whether or not, as William Shatner claims, better effects or even the ominous stone creatures he wanted for the film’s finale but was denied for budget reasons would have made the film better in the end is up to debate. What is certain is that “The Final Frontier” was considered a flop at Paramount and the sixth and final film with the original cast only came about because Paramount did not want to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of “Star Trek” without a film in the cinema.

For “Star Trek VI – The Undiscovered Country”, they once again relied on the experience of ILM, who were able to contribute their expertise to the destruction of the Klingon moon Praxis and the morphing of the model Iman into William Shatner.

Back to television

While “Star Trek” had established itself well as a franchise in the cinema, Paramount wanted to bring the Enterprise back to television. And even though “Star Trek – The Next Generation” was seventy-eight years past Kirk, Spock and co. in the future, there were to be some synergies between the franchise in the cinema and the new series on television in the here and now. For the pilot episode “Encounter at Farpoint”, ILM was once again commissioned to create the visual effects for the new Enterprise.

Probably the most important shot here is the scene in the opening credits in which the Enterprise goes to warp speed. The rubber band effect, where the front part of the ship appears to be flying away while the rear part is still stationary, was created by a combination of motion control, slit scan and the use of a streak camera.

The original plan was for ILM to create a kind of stock library of effects shots, which would then be used as required during production, thus minimising the need for new effects shots. However, it was soon realised that, apart from the usual fly-by shots, each script required very individual settings, so this library could only be used to a limited extent.

It was originally assumed that around ten new effects shots would be needed per episode. However, this very quickly levelled off at an average of sixty effects shots, and in particularly effects-heavy episodes it was as high as one hundred. However, the aforementioned warp effect was so complex and cost-intensive to produce that there were only two different shots available for the 178 episodes in which the Enterprise went to warp – because even though the effect only lasts a few seconds each time, the pure shooting time for a single shot was two days due to the many passes and long exposures for the rubber band effect described above.

It is interesting to note that the producers of the new series were seriously considering realising the effects entirely in CG at the time – in 1987. It would be another six years before another science fiction series – namely “Babylon 5” – was prepared to take this risk. The documentary “The Trek not taken” (included on the Blu Ray edition of “The Next Generation” Season 3) shows fascinating test footage and is astonishingly open about the decision-making process as to why the decision was ultimately made in favour of classic model shots.

What was a massive innovation in “The Next Generation”, however, was that it was edited on D1 video. This decision not only brought cost savings, but also greater flexibility. Phaser beams could now be created on a real monitor, effects footage could be used and reused much more flexibly and new effects systems such as Quantel’s Mirage and later Harry and Henry were used. And it was only with this change that the desire for a serious stock library could be fulfilled: From the third season of “The Next Generation”, the effects shots were also no longer optically printed, but digitally comped. And so the same shot of the Enterprise could also appear in orbit around different planets.

The transition to CGI

The success of “The Next Generation” heralded the first golden age of Star Trek. This became apparent in 1993 when a second Star Trek series was launched in parallel for the first time with “Star Trek – Deep Space Nine”

was launched in parallel. While CGI elements tended to be the exception in “The Next Generation”, such as the crystal being in “Silicon Avatar”, “Deep Space Nine” was to have a main character, the shape-shifter Odo, whose production included regular morphs. The company responsible for this was VisionArt Design & Animation; this iconic effect was designed by Dennis Blakey, who was deservedly honoured with an Emmy for his work.

in 1995, “The Next Generation” left the TV screen for the cinema, making way for “Star Trek – Voyager”. Star Trek on television was a well-oiled machine at this point, and so things were done the way they had always been done. In terms of the spaceships and stations, this meant that in the mid-nineties, most of the filming was done with models and miniatures. But science fiction was booming and so there were several other shows vying for viewers’ favour.

One of these was the ambitious “Babylon 5” by J. Michael Straczynski. The exterior and effects shots for this show were entirely CG, rendered on several Amiga 2000s with Video Toaster hardware and the associated Lightwave 3D. That way, Foundation Imaging, the VFX vendor for “Babylon 5”, avoided the purchase of expensive Silicon Graphics hardware. This cost saving turned out to be so successful that the producers decided early on in the course of “Babylon 5” to realise the effects “in house” using the same business model, and so Foundation Imaging was relatively quickly left without its biggest customer.

Star Trek Voyager was just in its first season at the time, but thanks to successful lobbying, more and more of the effects went to Foundation Imaging. Foundation Imaging took over the CGI model that Amblin Imaging had previously created for the title sequence – in fact, the CGI model was used in three shots, in the others it is a classic model – and prepared it so well in the episode that from the fourth season of Voyager onwards virtually all exterior shots were created in CG on this basis. However, the need for CGI also grew on the sister show “Deep Space Nine”.

The more the conflict with the Dominion came to a head in the show, the more opulent the space battles became – these scenes could not have been realised with classic models and motion control. Originally, there was to be a fixed separation, with Foundation Imaging responsible for “Voyager” and Digital Muse for “Deep Space Nine”. A nice plan, but it didn’t do justice to the reality of production. For example, Foundation Imaging helped out with the finale of the fifth season of “Deep Space Nine”, “Sacrifice of Angels”, to stage the conquest of the space station by the Dominion.

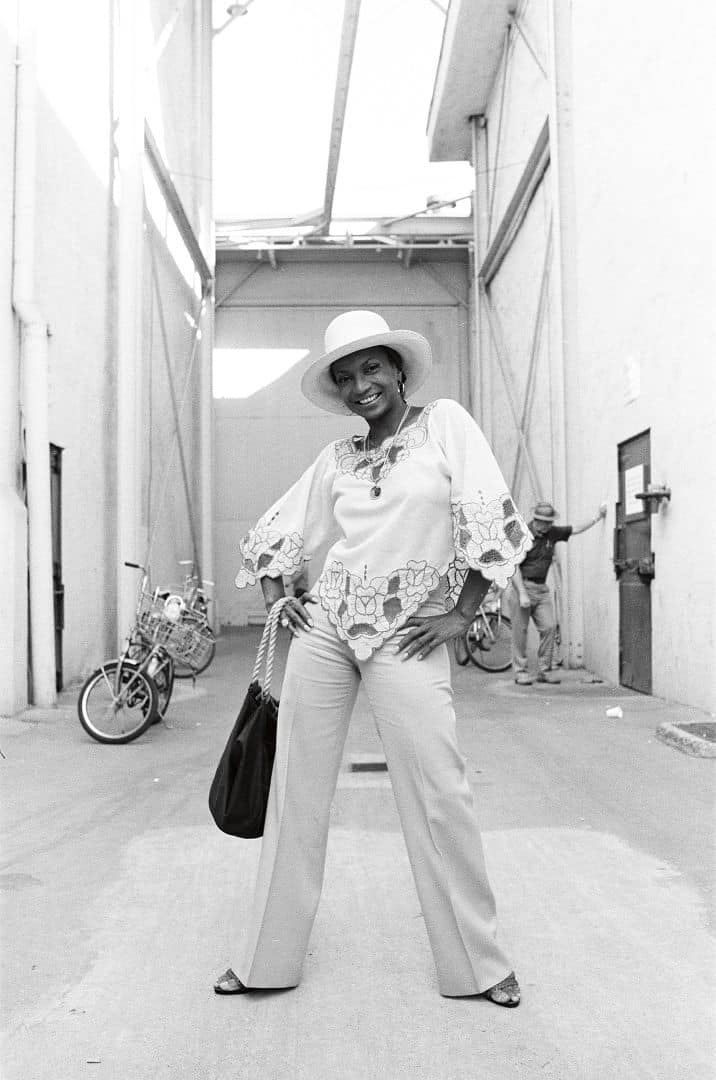

How to meet up legends

The “Deep Space Nine” episode “Trials and Tribble-ations” was a highlight in more ways than one. In view of the franchise’s thirtieth anniversary at the time, the idea was to take the crew around Sisko & Co. back to the time of Kirk and Spock – and have them meet their heroes there. The concept gave the producers quite a headache. Although Paramount had just released “Forrest Gump”, a film that accomplished exactly the same task – integrating a contemporary actor into old archive material – the question remained as to whether this was also possible within the constraints of a television series.

The answer came when the team led by VFX supervisor Gary Hutzel showed the producers a scene from the original episode “The Trouble with Tribbles”. They were a little confused as it was just a normal scene. It wasn’t until the second playback that they noticed the security officer in the background, who was not an actor from the sixties but a VFX artist from the nineties. With this proof of concept, one of the most elaborate Star Trek episodes of all time was given the green light.

As the original model of the Enterprise was on loan to the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, Gary Hutzel had a new model built. Unfortunately, the models of the Klingon ship and the K-7 space station had been destroyed in the meantime, which is why new models had to be built as well. To this day, it has to be said that the effort was well worth it – the effects still hold up today and the attention to detail of everyone involved can be seen in every scene.

Rarely have VFX and the on-set team worked so closely together as on this episode. Parts of the original sets of both the Enterprise and the K-7 space station were recreated. The typical lighting of the original series was meticulously recreated. The original negative of the old episode was completely rescanned and the corresponding scenes were matchmoved. With the help of a lot of compositing and rotoscoping, wonderful scenes were created in which O’Brien and Bashir help Scotty and Chekov in a brawl against the Klingons and Dax is allowed to pine after her dream Vulcan. No expense or effort was spared for the exterior shots either.

Meanwhile in the cinema

When “The Next Generation” said it’s farewell to the television screen, this crew went straight to the big screen. Within two weeks, the existing sets were polished up for the cinema and the long-awaited, but ultimately somewhat disappointing, meeting between Captain Kirk and Captain Picard took place.

Even if the film falls short of its potential, the makers did take advantage of one opportunity – they got rid of the model of the “Next Generation” Enterprise that the VFX artists hated in a spectacular way. The NCC-1701-D was often referred to as the “Hilton Hotel in space” due to its wide curved shapes and its aesthetics borrowed from the 1980s. In fact, the model was extremely difficult to stage due to its size and proportions. So what could be more obvious than to blow it up?

The resulting sequence is truly impressive: the Enterprise’s large saucer section separates from the engine section about to explode and tries to escape, but is pushed into the atmosphere of a planet by the force of the explosion and crash lands in a jungle. This landing in particular, as this massive saucer mows away row after row of trees and leaves a trail of devastation, is a prime example of believable shots with miniatures and models.

Two years later, it was time for the Next Generation crew’s first independent adventure. “First Contact” not only had the Enterprise crew travelling through time again, it also brought back the most feared antagonists: the Borg. To give the huge collective a face, the filmmakers created the Borg Queen. In order to showcase this symbiosis between the natural and the artificial, there is a scene in the film in which the Queen’s head, complete with mechanical spine, is placed in a torso. Here, too, plenty of matchmoving, CGI and morphing were used – if there was anything at all to criticise about this scene, it was that the original one-shot was subsequently intercut.

“Star Trek – Insurrection” followed and, like the two previous instalments, got the Industrial Light & Magic treatment. Only with the last of the four “The Next Generation” films, “Nemesis”, did the effects go to another company, this time to Digital Domain. And as with the television series, the trend here was increasingly towards digital models, although the company did not want to completely abandon the miniatures – these were used in the Enterprise’s ramming manoeuvre with the Reman ship.

Back to budget

in 1999, “Deep Space Nine” ended its run with seven seasons and 176 episodes, followed two years later by “Voyager”. The management at Paramount wanted to launch another Star Trek series, this time, in keeping with the times, a prequel. For “Enterprise”, they used completely digital models for the first time. They also had the foresight to produce the series not only in 16:9, but also in HD – even though the effects were only produced in 720p.

Unfortunately, “Enterprise” was not very successful. Various factors, which were summarised by the producers at the time under the term “franchise fatigue”, but which were much more complex, did not put “Enterprise” under a favourable star. The fact that “Nemesis” was squeezed in between “Lord of the Rings – The Two Towers” and “James Bond – Die Another Day” at the box office didn’t really help either and so the third season of “Enterprise” was supposed to be the end. Only the switch from film to HD video and slashing the budget by half made the fourth season possible, which is still regarded as the best by many fans today.

Remastering

But before “Star Trek” was sent back to sleep after seventeen uninterrupted years on air, a whole new chapter began that brought its own challenges in terms of VFX: remastering.

Let’s go back a little, more precisely back to the first motion picture, “Star Trek – The Motion Picture”. As described at the beginning, the film was made under enormous time pressure and never received a proper polish. Director Robert Wise considered the version that was shown in the cinema at the time to be a rough cut. To make matters worse, an “extended version” was released on the American channel ABC in 1983, in which unused material was added in, bloating the film up even more.

This version included a scene in which Kirk leaves the Enterprise and the entire studio construction, including tripods, can still be seen on the right-hand side. in 2001, Foundation Imaging, together with Daren Dochtermann, David C. Fein and Michael Matessino, set about creating a real director’s cut of the film under the direction of Robert Wise – twenty-two years after the release of the original version.

Cuts were trimmed, the sound was mixed better and effects shots were either reworked or in some cases even completely recreated. For example, obvious logical errors were removed, such as the fact that Spock holds his hands protectively in front of his eyes on the planet Vulcan to avoid looking at the sun, which was simply not present in the original edit. And “V’Ger”, the film’s antagonist, also finally takes shape in the Director’s Edition. In the original version, you could always see the energy cloud surrounding V’Ger and close up shots, but never the ship in its entirety, which was somewhat underwhelming.

Last but not least, dialogue scenes were removed that were obviously only there to explain missing effects shots on the narrative level. And all this… in standard definition. With the advent of Blu-ray and streaming services, to call this cost-cutting measure by the studio “short-sighted” in retrospect is a grandiose understatement. It was to take another 20 years before the 4K remaster of “The Motion Picture” was released in April 2022.

However, this experience was not the only reason why Paramount and CBS in particular, who now held the rights to the TV series, began to think more long-term. The effects of the original series in particular no longer really stood up to modern viewing habits. After there had already been several “digitally mastered” versions of the series as a video release, a remastering was to take place in 2006, just in time for the fortieth anniversary of the series, which would bring the original series into the 21st century:

All 79 episodes were re-scanned, re-graded, the sound optimised and, what was definitely considered controversial at the time, new CGI scenes of the Enterprise were produced. CBS Digital, which was responsible for this, faced several challenges: Firstly, the aesthetics, the pace, the whole style had to match the legal content from the 1960s.

The credo that Mike and Denise Okuda, who worked as consultants for CBS Digital, issued to the team was simple: the effects had to look like the original team behind Gene Roddenberry would have done them if they had had the technical possibilities of 2006. Nevertheless, the constant repetition of shots, which was unavoidable in the original version for cost reasons, should no longer occur. The aspect ratio remained conservative: the old series was designed for 4:3 and that’s how it should stay.

Anyone watching it on a modern-day disply will have to live with pillar boxes. But there was another problem in addition to tight deadlines: as the show was cut to film and the uncut rushes were no longer available, the new scenes had to be exactly the same length as the original shots. It became even more complicated when effects shots were faded. But no expense or effort was spared when it came to cleaning up the old negative.

What the software did not recognise as dirt or scratches was painstakingly painted out frame by frame on Flame and Inferno. The new “remastered” versions are now available on Netflix, iTunes and the like. However, a special feature is reserved for Blu-ray owners: Here you can seamlessly switch back and forth between the original and remastered effects.

The CBS Digital team worked on these remasterings for three years. After that, “The Next Generation” was to receive a similar remastering, but the challenges here were completely different. Unlike the original series, “The Next Generation” was comped and edited on video. This meant that over 25,000 rolls of film had to be retrieved from the archives, scanned in HD, cleaned and graded. However, a different approach was taken for the effects shots, as the negative with the individual elements of the effects was still well preserved.

And so the shots from the eighties and nineties were scanned layer by layer and recomped in Flame. Although some of the planets were given more detail, the camera angles and movements remained very close to the original. Other effects, such as screen inserts, beaming or phaser beams were recreated in HD, but only very rarely did they deviate stylistically from the SD original. In “The next Generation”, the preserving approach was even greater than in the original series.

One would expect that “Deep Space Nine” and “Voyager” would also be brought up to date afterwards, but fans are still waiting in vain for this to happen. Remastering the first season of “Next Generation” alone cost CBS Digital nine million dollars at the time. At the same time, Blu-ray sales were slowly dwindling in favour of streaming.

To make matters worse, as already described, “Deep Space Nine” and “Voyager” relied more and more on CGI in their initial production rin. The assets were considered lost in the meantime, as shops such as Foundation Imaging have since closed their doors. You can get a small glimpse of how good “Deep Space Nine” would look in HD in the documentary “What we left behind – a Look back at Star Trek Deep Space Nine”.

Thanks to very successful crowdfunding, the producers of that documentary were able to remaster fifteen minutes of footage in HD – including the breathtaking battle from “Sacrifice of Angels”. It seems that someone had made a backup of old Lightwave files after all. Whether and when fans will be able to enjoy full length high-definition episodes of these two series is still uncertain. Some are hoping for AI upscaling, others for Paramount, the streaming service where Star Trek now has its home.

in 2005, “Enterprise” went off the air and Star Trek disappeared into its second slumber. Star Trek was not due to return until 2009, but in a big way. The Enterprise was to return to the cinema and also be freed from the moderate budgets that had accompanied the film series from the second part onwards. The film was directed by J.J. Abrams.

The whole look was to be younger, more modern and more realistic. The effects were once again handled by Industrial Light and Magic, this time under the direction of Roger Guyett. What really sets the film’s effects apart is the focus on a realistic environment. A scene in which Kirk and Sulu jump onto a drilling platform high above the planet Vulcan was actually shot on a replica of part of this platform outdoors.

The rest of the platform was added in CG afterwards, but you can tell that the actors are in a tangible environment and that they are standing in real sunlight. None of this is unusual today, but when you consider that films like “Revenge of the Sith” were shot entirely in front of blue and green screen just a few years earlier, it’s fair to say that “Star Trek” (2009) was definitely a trend-setter here.

in 2012, “Star Trek – Into Darkness” continued in the same vein. And in the meantime, the shots were also distributed to several service providers, which is why Kirk & Co. were also worked on at the Pixomondo locations in Frankfurt and Stuttgart. 2016 saw the release of “Star Trek – Beyond”, the latest member of the Star Trek cinema family. Over 900 people around the world worked on the VFX, at least 300 of whom were credited in the end credits after tough negotiations. With streaming, increasingly on Paramount , Star Trek is currently experiencing its second golden age and continues to set standards in terms of VFX.

Conclusion

While in other franchises it was the visions of the respective creators that pushed the boundaries of what was possible with VFX, with Star Trek it was often more a matter of necessity. In the beginning, the pressure to take viewers to alien worlds in twenty-six episodes a year made them inventive. Paramount’s blind booking of “The Motion Picture” acted as an incubator for the still very young VFX scene in Hollywood and the Genesis sequence was an opportunity for Ed Cadmull’s team at Pixar to show where CGI was still going.

Later, “Voyager” filled the gap in Foundation Imaging left by “Babylon 5” and paved the way for CGI in the science fiction genre, from which other shows such as “Battlestar Galactica” would also benefit.

The fact that Star Trek’s effects were often enough orientated towards what was feasible is what makes them so interesting for our industry. Because in the end, the famous song line is true: “Space may be the

final frontier, but it’s made in a Hollywood basement.”