For The Fantastic Four: First Steps, Digital Domain contributed nearly 400 shots spanning character builds, creature effects, and dialogue-driven sequences. At the centre of the work stood The Thing, Baby Franklin, and the retro-futuristic robot Herbie, with Digital Domain tasked to balance comic-book authenticity and emotional believability.

We spoke with Phil Cramer, VFX Supervisor at Digital Domain. Jan Philip “Phil” Cramer is Visual Effects Supervisor at Digital Domain and a veteran in character animation and facial performance work. Over more than a decade at the studio he has led on marquee Marvel projects: turning Josh Brolin’s performance into Thanos in Avengers: Infinity War/Endgame, crafting the title character in She-Hulk: Attorney at Law, and working on Deadpool, X-Men: Days of Future Past, Ender’s Game, among others.

DP: Could you walk us through Digital Domain’s overall contribution to The Fantastic Four: First Steps. Nearly 400 shots across multiple characters and sequences?

Phil Cramer: We had the unique opportunity bringing some of the most Marvel iconic characters to life. Our main focus was creating the Thing, Herbie, and Baby Franklin. We also helped work on Johnny Storm, Mr Fantastic’s experiments, and Sue’s powers. A lot of our work was centered around the Baxter Building, our heroes’ headquarters. Our focus was often the character and dialogue driven story beats, leaning on Digital Domain’s character experience.

DP: The Thing was an asset shared across multiple vendors. How did you establish consistency in performance and look across studios, and what role did your Masquerade3 pipeline play in this?

Phil Cramer: Over the years, sharing between vendors has more and more become a standard, especially on Marvel shows. Fantastic Four, however, was a special example of camaraderie unlike anything I have seen before. From day one, each vendor’s VFX supervisor would join a weekly design meeting with Ryan Meinderding, Head of Visual Development at Marvel Studios. After The Thing’s look was locked down, I was tasked with finding the best capture and FACS combination to suit every vendor’s needs.

Once our Motion Capture Supervisor Connor Murphy identified Masquerade as our main facial solver for the show, Digital Domain processed and provided over 1500 post-viz assembly shots to The Third Floor, ILM, Sony Picture Imageworks, Framestore, and our internal team. This became a critical building block for our main character, The Thing, and allowed everyone to start from the same point.

In comparison, for Thanos, we only shared the asset itself, but the facial work would fall on each vendor’s proprietary system together with the huge development burden to come up with the same look twice.

DP: Masquerade3 is mentioned as a key innovation. Could you explain the major advancements of this version compared to previous pipelines?

Phil Cramer: Masquerade3 has significantly advanced our facial capture pipeline. The biggest change is the markerless approach, which completely streamlines the entire process. This means the actor can suit up, put on a helmet camera and jump straight into the scene. Normally, we would need to apply the facial markers at least 1 hour before the shoot, with touch ups as needed throughout the day. During Covid, masks would constantly smudge the markers. Due to this, we would constantly need to rely on re-calibrating the system based on the subtle changes to the marker layout. On She Hulk, for example, we were drawing in daily calibrations.

In addition, we are now able to run solves on the entire footage captured and run it via a command line blindly. In the past, we would receive “selects” per shot and have facial artists process this data. Now, we are literally running our system on the ENTIRE dataset overnight. This mass processing allowed the FACS system to be used by the Third Floor for postviz, as well as all the final vendors.

A nice little side development for The Fantastic Four: First Steps occurred during our additional photography shoot. Ebon Moss-Barach had to have a beard due to his other commitments. With a markered system, this makes the data useless (in part because the beard covers the markers or makes the markerset inconsistent). With Masquerade3, this proved to be no issue and we were able to solve at the same quality all Ebon shots with a beard.

DP: Processing 60 hours of facial footage sounds like an enormous data challenge. How was the workflow structured between capture, processing, and integration into final animation?

Phil Cramer: Over the past few years, our facial processing has evolved drastically. While we used to process the data on a per shot basis, we now are batch processing all captured data per character. This means, we no longer have facial artists spend significant time on each individual shot. We focus on an overall correlation between the actor and the character via animation. Once this is established, we can consistently produce results at very high quality, but solved blindly via the command line.

We would mimic every night the entire facial delivery from Marvel with matching animation files. This was critical to allow all other finals vendors as well as the postviz vendor, The Third Floor, to utilize the Masquerade3 facial solve provided by our team. Once this became a critical step for each vendor, we set up an assembly team under Connor Murphy. He processed and set up over 1500 “layout” files with facial and body mocap. This helped keep all data consistent and allowed for the most advanced starting point.

DP: How did the team balance the comic-book heritage with the cinematic portrayal of a believable infant?

Phil Cramer: Franklin had to be a believable baby at the core of it all. He was meant to be as realistic as a baby as possible, with no special powers. This was so important that we conducted a full test with Matt Shackman about two years before the release of the film. We even used my own newborn son, Cosmo Cramer, as the test baby to better understand how to consistently and convincingly replace a real infant..

We knew consistency of the babies was the highest priority. We captured endless performances of the baby actor portraying Franklin. We captured a wide range of baby motions in 4D for training and as potential face replacements. In the end, we used all sorts of techniques to create Franklin, but the dominant approach focused on head replacements with a full CG head.

DP: For Baby Franklin, you used both Charlatan and a baby-friendly scanning booth. Can you explain how those workflows were adapted to make the CG infant believable while working within (ethical and) practical limits of filming with real babies?

Phil Cramer: From the very beginning, the baby was high on every list of show priorities. We needed an effective solution to capture the best possible performance, while also respecting the limited on-set time for baby actors. Because of this, we had around 30 stand-in babies that VFX needed to make look like one single, consistent baby character.

Capturing a precise performance from a baby is practically impossible as they cannot be directed. And, we did not want the audience distracted by an artificial baby’s performance. Director Matt Shackman came up with the notion of accidental acting. Every day, we’d set up the same critical scenes with the hero baby and stunt actors in the hope to get the right beat on an emotional level. This was a very important aspect for the resurrection sequence after the final battle, when Sue stops breathing, and the Fantastic Four along with Baby Franklin gather around her, believing they’ve lost her.

For most of the other scenes, we needed a versatile baby setup with a strong CG asset at its core paired with lots of training and reference material. Clear Angle helped us set up a baby rig that allowed a young baby to be sitting in it for hours at a time, with easy access for the parents. We needed to ensure we can capture the highest level of detail under the lowest possible light to protect the baby’s eye.

DP: You also worked on fire, invisibility, and ultrasound effects. How did you approach combining procedural effects with narrative-specific ones like the pregnancy ultrasound?

Phil Cramer: Sue’s power from the get go had some really interesting, classical looking FX work. The highlight for us was the baby ultrasound. Our FX team tried to generate pleasing looking, but highly detailed internals. We wanted to reveal the baby in many layers, but it could not be too medical. So, we tried a more ethereal approach to show the inside of the human body, focused on refractions and different lens aberrations. The beauty of this scene was critical. In fact, it was one of the first development tests we did on the show utilizing a stunt woman with a prosthetic belly.

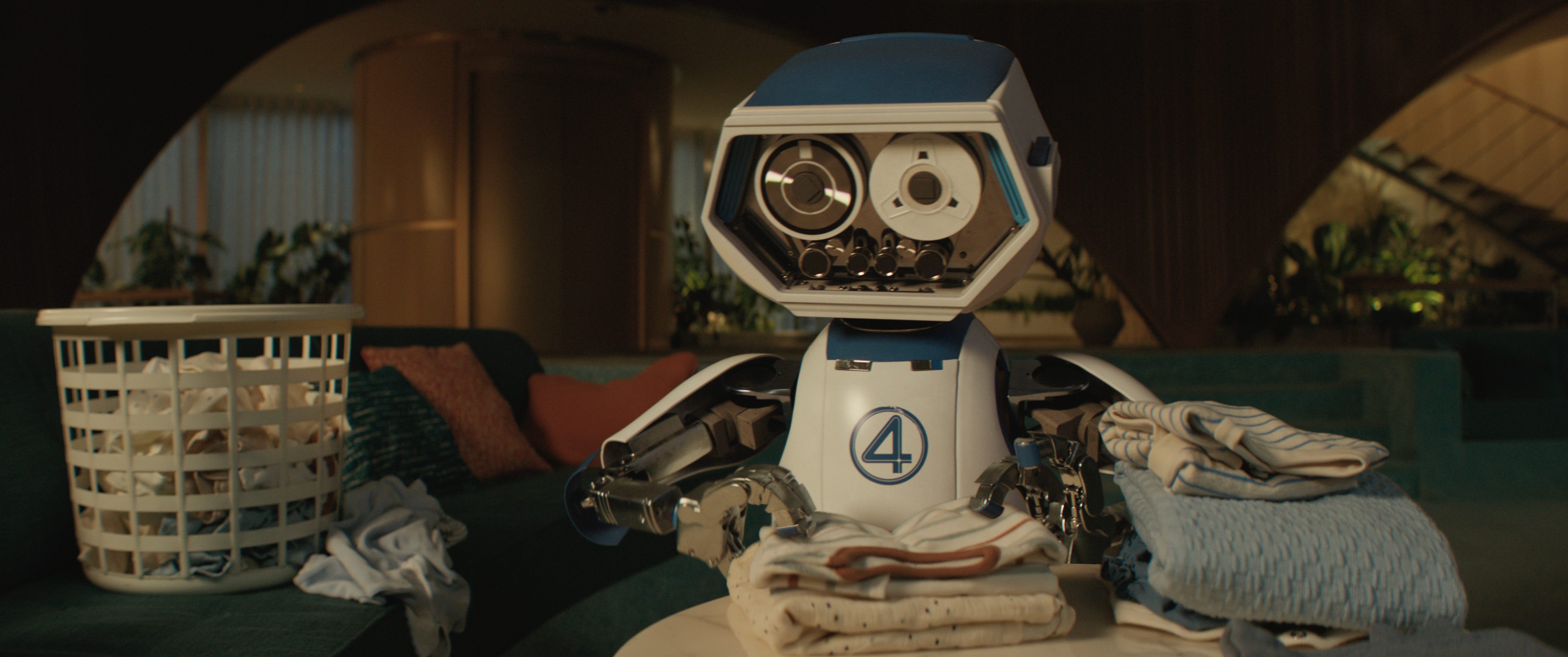

DP: HERBIE seems to combine hard-surface modeling with comedic character animation. What kind of rigging and animation workflow did you build for him, and how did you integrate “mechanical logic” with slapstick humor?

Phil Cramer: Herbie is such a wonderful part of the Fantastic Four universe and we wanted to make sure he fit right into the 60s style world. On set, there was a matching puppet that was used to show the actor’s where Herbie is at any given moment and that they could interact with. A puppeteer was also present at all times.

Most of the Herbie motions were based on the overall puppeted performance. We would normally track the overall body motion, but then enhance it in animation. This added to the realism, as he kinda was real. I love characters with limitations, and Herbie is one just like that. It helps ground a character into realism. Herbie was quite limited to his ball motion (yes he could fly, but he would barely utilize his skill). Herbie ended up being a lovely house robot that anyone would like to have.

DP: Nine costumes for The Thing, plus facial hair simulation. How did your team manage asset complexity and cloth/hair simulations across so many variants of basically a pet rock with anger issues?

Phil Cramer: The Thing’s character is not like many others in comic book lore. He is not happy with his super powers, in fact he wants to hide them. He is also ashamed of his new look. He is constantly trying different ways to hide his body and face, even to the point of growing a beard. I love this kind of a character. It shows the imperfections we so often miss in superheroes.

Our Asset Supervisor Ron Miller made this process feel easy. Once we established a good collision mesh for the Thing’s body, we dressed all the costumes against it. Production helped us a great deal by having a stand in actor in a prosthetic suit available for any shot. He would always wear the correct costume tailored to The Thing. This really allows you to ensure you match the properties of the design, rather than make a CG costume.

DP: The film leans heavily into a 1960s retro-futuristic design language. How did that aesthetic influence your VFX choices, from Baxter Building interiors to character look development?

Phil Cramer: All the FX were meant to have the same 60s feel as the actual world did. So we set out to look for traditional looking FX from that era, but done with today’s tools. Sue’s refraction edge break up falls in this category. We wanted to find an effect that would look like classical color blocking, while being executed in a modern way.

For the baby proofing sequence in the Baxter Building, we had to look for all sorts of period correct baby proof devices. Lots of fun for the team to find classical fire detectors, etc.

DP: With characters like The Thing and Baby Franklin, there’s always the “uncanny valley” problem. What were the biggest creative decisions to make them feel both comic-book authentic and emotionally relatable on screen?

Phil Cramer: The Thing himself was grounded in the artwork of Jack Kirby. The goal was a character reflecting the design and spirit of the original Thing by Jack Kirby. We wanted to find ways for the lighting to shape him similar to the 2D drawing, i.e. very bold light and shadow play.

Franklin was its own story. He is not purple or made out of rock. Everyone has seen a baby before, so everyone will be able to judge. Our goal was to approach every shot in a unique way, and to not give away our hand. As far as performance was concerned, we always needed to ensure the baby behaved like a baby in that age… so no superhero things. Franklin could only do what a 4 – 6 month old baby could do… which is close to nothing :)

DP: Were there specific sequences where VFX had to “step back” to let the actors carry the scene, and others where VFX had to “take over” entirely?

Phil Cramer: I feel Digital Domain’s scope of work is dominantly in the “step back” category. Meaning, we ended up having a lot of the story driven sequences of all our main characters. It wasn’t about anyone in particular, but the Fantastic Four team learning and planning together as a family. The Thing behaved pretty much like an actor. He was not about action, but acting. So our job on set was to stay out of the way. We wanted to encourage the creative process between these four brilliant actors, and make them forget about the technology.

DP: Marvel films often balance spectacle with continuity across the MCU. How did you ensure your work fit seamlessly into the larger Marvel visual language while still creating something fresh for Fantastic Four?

Phil Cramer: The Fantastic Four: First Steps was intentionally set in a different multiverse to feel free and fresh. We tried to make each effect and character look and feel different from the regular MCU. Having worked on so many MCU features and episodicals, this was a nice, new experience. It all started with the 60s look of Matt Shackman’s world. From there on, every aspect was meant to break the typical approach. As an example, the Things had to be based on Jack Kyrbi’s original work. He was meant to bring the original drawings to life… in a modern form.

DP: The Thing’s beard became both a character trait and a technical challenge. Was this a case where creative direction and technical innovation directly influenced each other?

Phil Cramer: Our Thing went from growing a stubble to a full fledged beard. Funny enough, so did the actor. We initially asked him to shave to accommodate the technology, but later allowed a full beard in support of his role on Season 3 of The Bear.

Growing the beard gave The Thing a lot of character, but, in turn, made the emotions harder to sell for the animation team. Our Animation Supervisor Frankie Stellato and his team did an amazing job still selling the same range of emotions, even with his face hiding under a full beard. Interestingly enough, a beard of that size is quite static. We ended up using a rigid body sim for the beard and it became part of our regular CFX dailies.

DP: You collaborated closely with other VFX vendors. What worked best in terms of pipeline sharing, and what lessons can the industry learn from this cross-studio cooperation?

Phil Cramer: Sharing is caring, especially on a Marvel show. Fantastic Four provided a very open environment for all companies to get together and share ideas. Early on, we all collaborated closely with Ryan Meinderding in a very open design process with all VFX supes involved. Marvel then tasked me with creating a common capture list for all the vendors, to ensure everyone gets what they needed to make their characters work.

This led us to evaluating Masquerade3 as the main solver for all vendors. It ensured everyone started with the same animation and the same base FACS shapes in their rigs. We did group Thing animation reviews with Production VFX Supervisor Scott Stockdyk, which really helped dial the character in. I think we all learned a lot from that process and I have a lot of respect for my fellow supervisors at ILM, Sony and Framestore. It was a unique experience and I hope we maintain this open approach on future projects.

DP: Looking ahead, do you see more projects adopting this kind of multi-vendor, shared-pipeline approach, especially around proprietary tools like Masquerade3?

Phil Cramer: I hope so. I feel this process helped everyone involved. In general, we need to avoid over-capturing/processing. These large scale VFX productions can be improved by being smarter about the capture and processing. Rather than having each vendor replicate the same ingest and training costs, this streamlines the process, and without really reducing the creative. It is like digital housekeeping.

DP: What would be your recommendations for artists or studios attempting similar workflows, shared assets, markerless capture, large-scale character development?

Phil Cramer: The assembly phase, led by Connor Murphy, was the crux of this shared production. It served as a central hub through which all motion traveled through, like a universal layout pass with both body and facial mocap.

How can you replicate that as a student or younger artist? I feel with the dawn of AI, lots of fun tools have become accessible. There are different forms of AI capture to simplify the body performance. Unreal offers some of the finest body and face retargeting. Try to replicate the core steps to capture a character.

DP: And finally: what’s next for you and your team? Are there upcoming projects you can tease for us?

Phil Cramer: My team is going from small to big… After focusing for two years on babies, we are now working with Godzilla and his friends :)