Table of Contents Show

Such devices have existed as gyrocompasses for navigation since the beginning of the century and even Einstein was involved in their further development (although the earliest approaches date back to 1743).

Enough history, our current devices for determining rotations and accelerations are tiny marvels of nanotechnology without actual gyroscopes. Instead, they are IMUs (Inertial Measurement Units), which are based on silicon surface micromechanics and can now be mass-produced at very low cost. This is why they can be found in almost every mobile phone, the remote controls of games consoles, TVs, and also in drones, gimbals and numerous cameras (sadly, also in cruise missiles or intercontinental ones). We’ll stick with the term ‘gyro’ here, as this is the term most camera manufacturers use.

The hardware

Image stabilisation in the camera or lens is already dependent on IMU chips. For some time now, many cameras have also been able to indicate in two axes whether they are being held horizontally – just like the artificial horizon in an aeroplane. However, it is only recently that some manufacturers have been recording the information from the IMU together with the video, e.g. Sony in the current high-end devices and, since firmware version 7.9, Blackmagic in the Pocket models. This means that this data is generally available for use in post-production, whereas previously, an action cam, a mobile phone or a separate measurement sensor had to be mounted on a camera frame.

Why the effort?

What are the advantages? The stabilisation in the camera is often designed for sharp hand-held photos with longer exposure times. Moving shots are much more difficult to stabilise because the control software cannot always distinguish between desired and undesired movements. It is also unable to work in advance to optimise image stabilisation over the duration of the exposure.

Conventional post-production stabilisation software, on the other hand, works on the basis of pure image analysis. It is therefore also not always able to distinguish between desired and undesired movement and can easily be confused by moving objects in the foreground. This also applies to short-term disturbances such as flares in backlighting and, last but not least, rolling shutter (RS) effects, which cannot always be distinguished from movements in the image. With sources prone to RS, such as hybrid cameras or smartphones, this leads to the infamous ‘jelly’ effects, which are even more noticeable after stabilisation. The problem is explained well here in a video from Stanford University.

Sony Catalyst

Even the free version of this software called Catalyst Browse can use the gyro sensor data from cameras such as the A7S III (DP 21:05) or the A7 IV (DP 22:05) (according to Sony also the A1, A7C, A7R IV and

A9 II). At first glance, it only seemed to work with Sony lenses, but with third-party lenses it depends on the manufacturer and possibly the adapter used. The beautiful Sigma lenses from the “Art” series work with E-mount or the MC-11 adapter, according to users on the net it should also work with branded adapters and Canon lenses (not tested by us).

Unfortunately, no data is recorded with manual lenses, such as vintage glass from Zeiss, at 100 or 120 fps in any case. The gyro sensor data was also recorded if the internal stabiliser was already running during recording. If the stabiliser is set to “Standard”, i.e. it only works with mechanical tracking of the sensor, it has quite an effect, especially with small shaking movements in static hand-held shots.

With the new “Active” setting in the A7 IV, which also works with slight cropping via firmware, slow, controlled movements were also calmed down well. Overall, however, we would recommend switching off the internal stabilisation if you want to work with the software. The internal functions are not so good at dealing with intentional camera movements and are of little help against the rolling shutter – walks with the camera look much better in Catalyst.

Of course, Catalyst Browse cannot compete with DaVinci Resolve (DR for short), but it offers quite good options for initial colour correction including waveform display. Alternatively, you can also leave log recordings in their original form, as stabilisation with gyro sensor data – unlike image-based stabilisation – is not dependent on good contrasts. Fortunately, even the free version supports high-quality output formats such as H.264 in 10 bit and 4:2:2 with a high data rate (up to XAVC Intra).

Quality fanatics with enough storage space could also output in DPX, but this is basically nonsense, as the cameras only output GOP codecs with gyro sensor data. The analysis is very fast, the rendering rather slow. On the Mac, it is somewhat disappointing that ProRes is offered up to 422 HQ, but only in HD or with a maximum of 2K. Quite incomprehensible, as the other formats allow up to 4K. The stabilisation reduces the resolution in any case, depending on the crop adjustment, but not by half. Nevertheless, the free version already offers external monitoring via Blackmagic interfaces, ensuring precise image control during colour correction. It also shows all the metadata of the clips, and you will find much more than DR is prepared to read at Sony. However, batch rendering is only possible here with identical settings for the sources.

The full version of Catalyst Prepare offers ProRes HQ in 4K, but still no ProRes 4444. There is also the export of DNxHD and audio in WAV or MP3 (yuk). The functions for organising your media are considerably more extensive and copies can be created with checksums. It even offers a rough cut via storyboard and export as EDL. With a monthly subscription for €13.95, this version doesn’t cost the world if you just need it for a project. A detailed overview of the Catalyst versions can be found here.

Blackmagic

With firmware 7.9.1 (the x.x.1 update contains important bug fixes), the Pocket models from Blackmagic finally offer the recording of gyro sensor data – the hardware was already available from the start. Unlike Sony, the data is recorded regardless of the type of lens. However, for lenses with their own stabilisation, this must be switched off, otherwise the function will be suppressed. In the “Setup” menu of the Pocket 4K there is also a switch for “Lens Stabilisation”, which must also be deactivated. With electronically coupled lenses, the transfer of the focal length works automatically; with manual lenses, you have to enter this in the “Slate” when shooting. Unfortunately, subsequent entry in the DR metadata list does not work – an annoying trap, as manual lenses seemed unsuitable during our first attempts.

Fortunately, this is not true, because if we had already entered the correct focal length for the shot, the results for manual lenses were just as good as for electronically coupled lenses. Sony could certainly do the same, but they want to sell their own lenses. Blackmagic, on the other hand, has its own cameras and (at least so far) does not use gyro sensor data from cameras like Sony or GoPro. Although the gyro sensor data is continuously recorded, DR has so far only used the focal length of the first frame. A zoom during the recording therefore still leads to unsatisfactory results.

The analysis in DR 18.0.1 when set to “Camera Gyro” takes the same time as with “Perspective”, but the results are much better. This is especially true for RS, where side effects are particularly noticeable in the image-based methods after stabilisation. This ‘jelly’ effect is largely eliminated with Sony and Blackmagic using a gyro sensor – after all, the manufacturers know their own sensors and their readout speed. All that remains is a slight flickering of high-contrast, horizontal structures with vertical vibrations, which is visually almost reminiscent of poor de-interlacing. It is difficult to tell whether this is due to briefly increased motion blur caused by fast, hard impacts or to residual compression or stretching caused by RS. Adobe’s After Effects offers a function called “Camera Shake Deblur”, but this hardly brought about any improvement in our test clips.

You should definitely practise the strenuous, dancing gait with the camera, where you don’t straighten your knees and don’t put your heels down. The results will be much better if you work with shorter aperture angles than 180 degrees. Unfortunately, this can disrupt the cinematic illusion of fast movements, so you may have to add artificial motion blur in post after stabilisation. This is especially true for spatial resolutions above HD if the temporal resolution is only 24 to 30 fps. In contrast to the image analysis, only the “Strength” factor is offered for the gyro sensor, without “Cropping Ratio” or “Smooth”, so that you have somewhat less control over the stabilisation, similar to Catalyst Browse. Cropping is stronger at the highest value for Strength than with optical analysis, but so is image stabilisation.

The new Pocket 6K

At this point, we would like to take a brief look at the new Pocket 6K model. In terms of price and functionality, it lies between the first generation (see DP 01/20) and the 6K Pro (see DP 01/22). It has the sensor in common with the latter and is identical in almost all other respects. It only lacks the internal ND filters and the brighter screen. So if you don’t fully trust the internal mechanics and prefer to use your own filters and like to work with a viewfinder in bright light, this model is a good choice. Including the OLED viewfinder, it costs no more than the 6K Pro without it. Both 6K models are ideally suited for image stabilisation, as there is still enough resolution for 4K or UHD even after the necessary cropping.

The new firmware

There have been a few more changes with firmware 7.9. In particular, the edge enhancement for the focus area, which was previously criticised by many users as inadequate, can now be set very flexibly, including the choice of colour and continuous control of the contour display. The autofocus has become considerably faster and more accurate with the appropriate lenses, even if Blackmagic cannot compete with Sony or Canon in this area. It is not without reason that the cameras have “Cinema” in their name and are aimed more at scenic work, where human focus assistance is usually used. Nevertheless, there is already an app for this: “Focus Puller” by Robert Meakin enables remote control via Bluetooth and even continuous AF on iPhones with LIDAR (albeit without object recognition).

Recording to SSD via USB-C is said to have become more reliable with 7.9.1 and you can now change the recording medium directly in the GUI. Control via ATEM mixer supports the use of the Pockets as a studio camera. However, in addition to all the improvements, there is also one point of criticism: the previously grey recording button has now been coloured red and only has a red ring when recording is in progress. This is not as obvious as the previous display, even if the running timecode is displayed in red. At this point, many people would like to see the previous appearance again.

Gyroflow

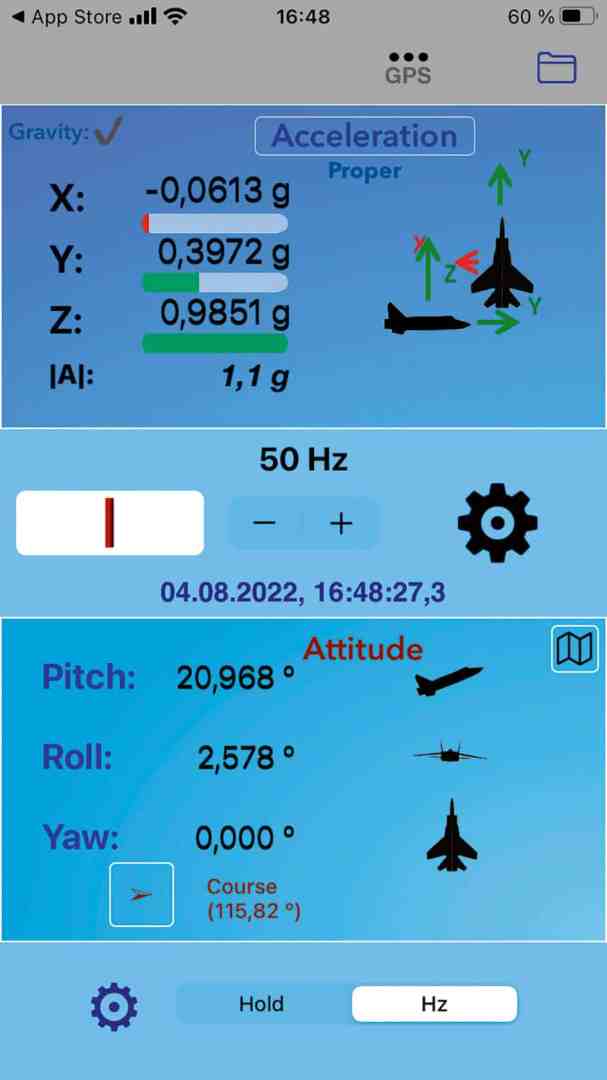

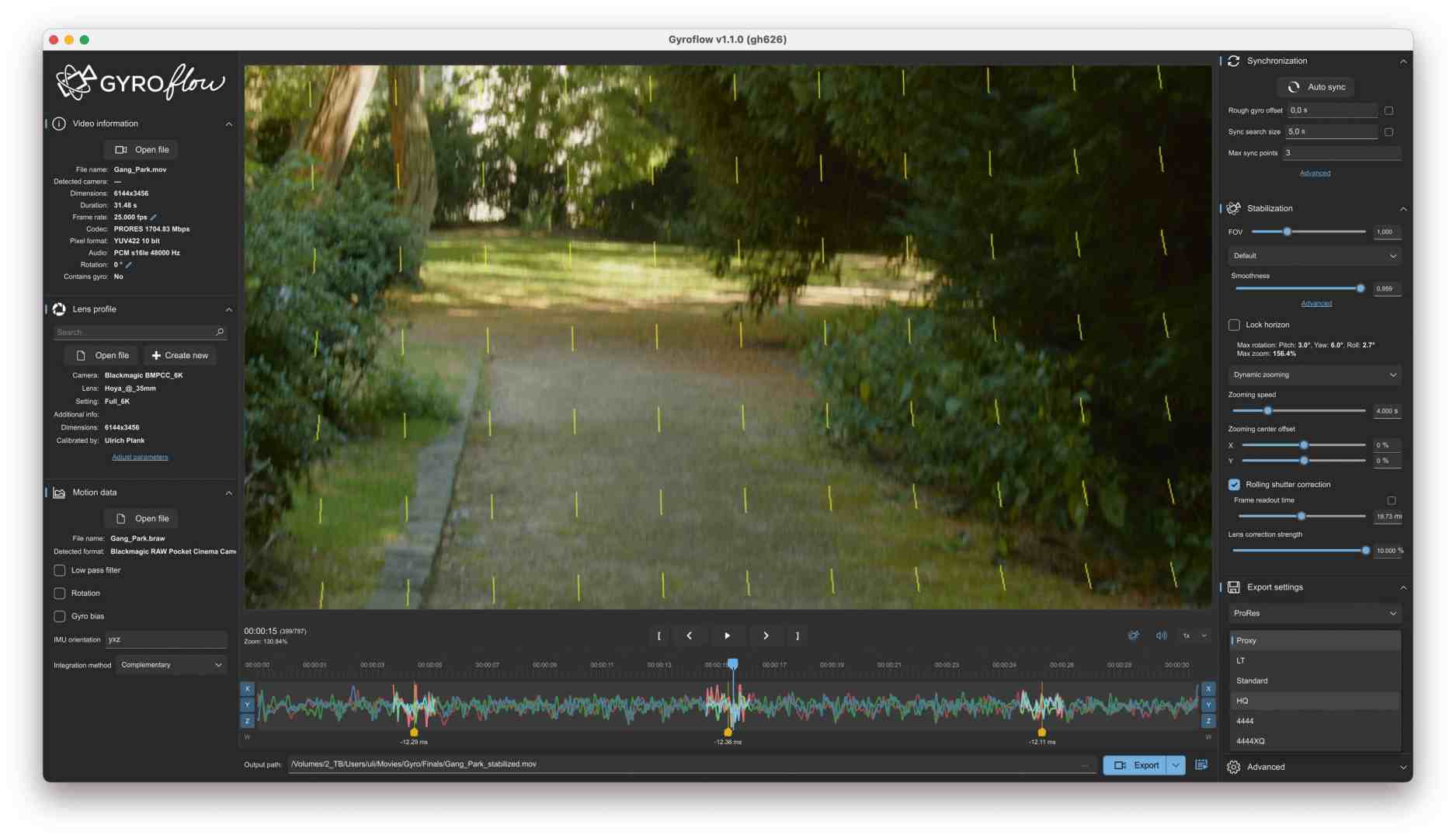

A free alternative is this donationware for all three platforms, which was recently further developed to version 1.2.0. It supports the widest range of cameras and also allows the use of additional sources for the stabilisation of cameras without gyro sensor data. These sources include iPhones with the GFRecorder or Androids with Sensor Logger, as well as GoPro from Hero 5 and other action cameras and even separate IMUs. Of course, such sources must be synchronised with the desired video. The software offers full support for this, in addition to a generally well-functioning auto sync, there are differentiated intervention options.

Not only can you load recordings from the above-mentioned Sony cameras directly, but with the new version you can also load recordings from cameras from Blackmagic or Red. However, ProRes from the pocket cameras does not contain any gyro sensor data. It should therefore be BRAW, in which case the programme uses the motion data it contains. The SDK from Blackmagic must be installed beforehand, but Gyroflow automatically points this out with the first BRAW clip and installs it on request. If at least the camera and lens are still available when metadata on the focal length is missing, Gyroflow can even solve this problem.

For perfect results, you still need a lens profile. This can be created directly in Gyroflow using the test chart and analysis programme. The software then asks whether you would like to share it with the community

Community – which is of course only fair, as is a donation to this excellent project. You can already find ready-made profiles for many combinations on the net using the search command. You will also need the exact value for the rolling shutter. The readout times for numerous cameras can be found at CineD, for example; if necessary, you can also visually adjust the value on a particularly conspicuous individual image.

The adaptive zoom can be controlled by other parameters, so that Gyroflow offers the most comprehensive adjustments for optimum results. Of course, this takes time, but the programme can deliver results comparable to those of commercial applications even with the standard values.

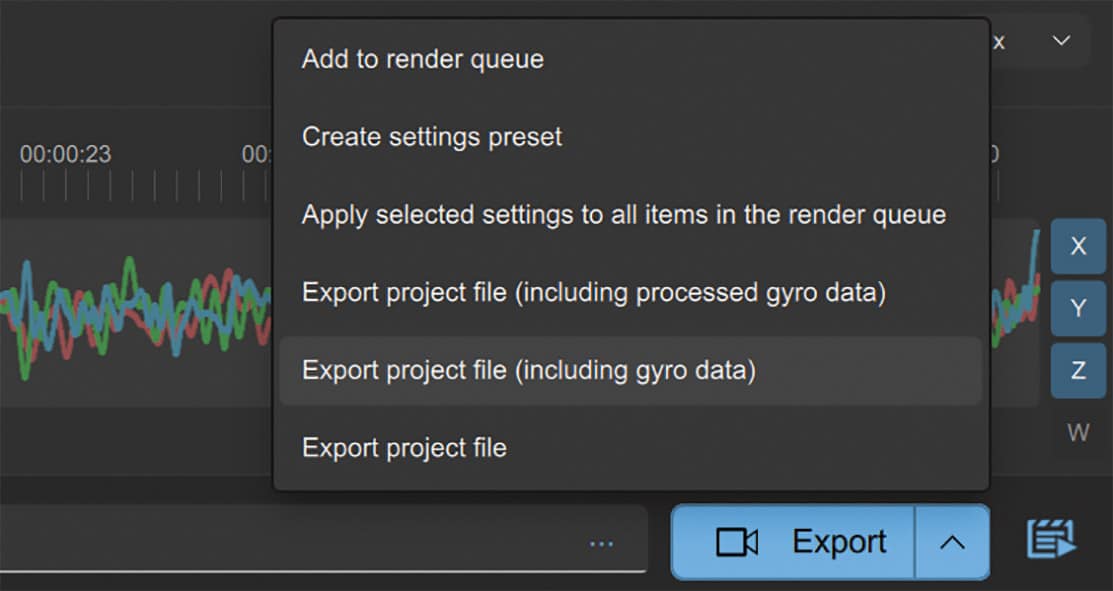

Gyroflow also leaves nothing to be desired when it comes to output; the stabilised material can be exported in very high-quality formats, but can also be compressed directly with x264 or x265 in good quality. Alternatively, you can output the stabilisation information generated in the program. With an OpenFX plug-in, this information is available directly in DR and other NLEs; all you have to do is enter the full path of the *.gyroflow file.

This means that all sources that the relevant video programme can process can be used without conversion. As BM has the above-mentioned SDK for BRAW with support for gyro sensor data, there is nothing to prevent third-party manufacturers from integrating further options. Conversely, it would be great if BM could use the data from Sony cameras, as the stabilisation in DR is at least as good as in Catalyst.

Comment

All three options deliver better results with unsteady shots than stabilisation by analysing the image content via software, especially with regard to rolling shutter artefacts. This puts Blackmagic’s pocket cameras largely on a par with the hybrid cameras from Sony or Canon in this area, albeit only after processing in post. The performance of Gyroflow is particularly impressive and does not have to hide behind the commercial solutions.

It would be desirable for DaVinci Resolve to be able to use a subsequently entered focal length, or even the recorded focal length per individual image for electronically coupled lenses. This would make it possible to realise the famous ‘Vertigo’ effect with counter-rotating zoom from the hand. Further utilisation of the gyro sensor data is conceivable in conjunction with the photogrammetric determination of 3D camera paths for VFX – there is still a lot of potential for development.