This article by Sabine Hatzfeld originally appeared in DP 03 : 2015.

For the film project “Le Gouffre”, Thomas Chrétien, Carl Beauchemin and David Forest quit their jobs, formed the Lightning Boy Studio and moved in together for cost and production reasons. A Kickstarter campaign brought the animated film with the unusual look to completion, which was nominated for an animago AWARD in the “Best Short Film” category in 2O14.

The trio met in 2006 at the Canadian college “Cégep du Vieux Montréal”(www.cvm.qc.ca). Carl Beauchemin and David Forest studied 3D animation, Thomas Chrétien 2D animation. In the third and final year of their studies, they decided to work together as filmmakers in the future. Thomas went on to complete a two-year 3D degree programme, while Carl and David gained their first experience in the industry.

After six months of developing the story, production finally got underway at the beginning of 2012 – despite all team members now working full-time. Carl and David worked as 3D animators at Modus FX on the first Canadian 3D feature film “The Legend of Sarila”, while Thomas worked as a VFX artist for mobile games at Gameloft(www.gameloft.com). There was only time for “Le Gouffre” at night or at weekends. So after six months, all three of them quit their jobs to work on their film full-time and only from time to time. To save costs, they also moved into a flat. We spoke to Carl Beauchemin about the project, which was successfully financed via Kickstarter towards the end. The film and makingof have been online on Vimeo since February this year(bit.ly/1zgSovu and bit.ly/1zMo3C1).

DP: Hello Carl, why didn’t you consider a crowdfunding solution or funding opportunity right from the start?

Carl Beauchemin: Our original plan was to get a government grant. But when you make a film for the first time, nobody trusts you. Our application was rejected three times in a row. At the same time, we realised that no company would support us as long as there were no presentable shots. That’s why we abandoned crowdfunding. Without actually rendered shots, how do you hope to convince people that you can make a good film?

DP: What hardware equipment did your budget allow for?

Carl Beauchemin: Each of us still had a good computer from our student days – because of the 3D homework. We also had a special computer at our disposal: in 2007 David submitted an illustration to a competition organised by cgsociety.com – and promptly took first place! The prize was a Maingear Shift(www.maingear.com), which we nicknamed “the beast” and which lived up to its name in the rendering.

DP: How was your pipeline structured?

Carl Beauchemin: The lion’s share of the work – i.e. modelling, animation, rigging, VFX, rendering – was done in Softimage. We also used ZBrush for the detailed work on some of the models. Concept art and storyboards were created traditionally on paper or in Photoshop. The compositing was done in After Effects and the editing was done in Sony Vegas. We also worked with Slipstream VX from Exocortex, a plug-in for Softimage. We used it to implement every particle simulation that can be seen in the film(exocortex.com/products/slipstream).

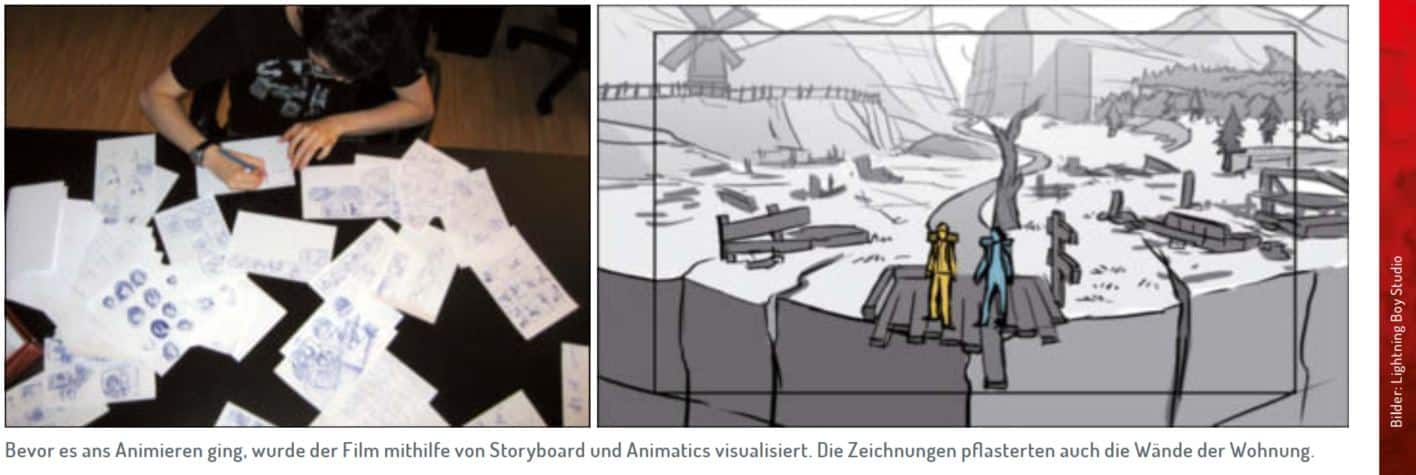

DP: How were Previs and Animatics used?

Carl Beauchemin: They were essential parts of our workflow. We spent months working on the animatic. We wanted to make sure that the timing was right and that the storyline was coherent. With the help of the Previs, we were able to create a rough version of our sets to get an idea of the proportions.

DP: What inspired you to make this film?

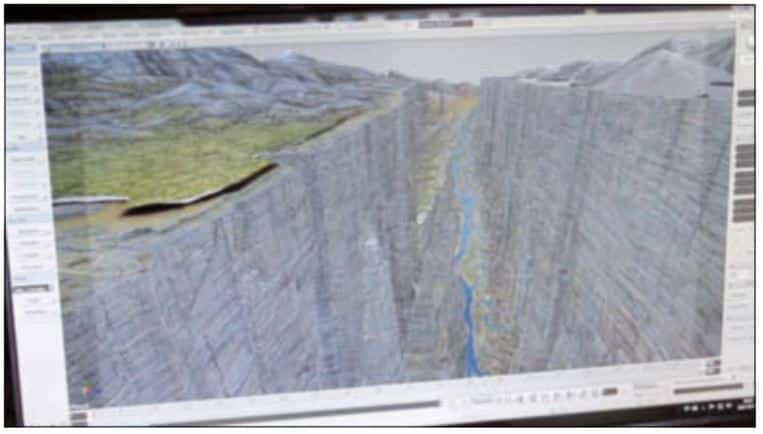

Carl Beauchemin: “Le Gouffre” is set in an undefined location. We did look at pictures of canyons, but we didn’t copy them one-to-one, we changed the scale and adapted them to our desired film look. For the characters, we focussed on a timeless look. We left out details such as zips or logos so that the design didn’t come across as too modern. Our aim was to give the film a special atmosphere, comparable to a legendary tale.

DP: How did the unusual look come about?

Carl Beauchemin: We had a very specific look in mind and it took us a long time to realise it. In the end, we had to paint all the textures by hand and find a clever way to put the shots together. During this process, we realised that in order to create a unique visual style, we had to forget everything we learned about compositing in school. Instead, we looked for a way to do it all in Photoshop with layers and paint brushes.

DP: How did you actually realise this for the sets?

Carl Beauchemin: For the sets, we first unfolded the meshes with UVs to assign the textures in medium resolution everywhere. This allowed us to make sure that everything looked good and looked painted from a distance. Up close, on the other hand, it sometimes looked really bad, but that didn’t matter: in such cases, we took a screen capture of the set from the camera angle of the shot and painted all the high-resolution details in Photoshop. We also often quickly created a greyscale texture shader for rendering in order to get more details on a new texture. Then we just had to project the whole thing back onto the original mesh. Of course, this only worked if the camera panning was not too strong. Otherwise you would have seen that the projection was expanding in a somewhat strange way.

DP: How did you approach the look of the characters?

Carl Beauchemin: Because they were animated, we couldn’t use the same projection technique. Instead, we relied on good, hand-painted textures and lots and lots of passes. We had a separate mask for the head, hands, eyes and hair, as well as for each individual item of clothing. We treated each light as if it were a colour layer. So we selected the exact colour we wanted to use in the lit scene and assigned it as a solid colour instead of having the layer in an additional mode. That helped us a lot to get rid of that classic CG look.

DP: Did you actually consider using an inexpensive MoCap system for animation references?

Carl Beauchemin: No. Firstly, that was never our intention and secondly, our budget wouldn’t have allowed it anyway. However, we ran through all the shots ourselves and edited them into a reference real film. This allowed us to see whether the flow of the film worked. We always tried to place the cameras in the same way as in the animated film so that we could also test whether the cuts worked. But the biggest advantage of the video reference material is that you can see all the fine little movements. This allowed us to make the animation in the film look as real as possible.

DP: What challenges did you face when rigging the film?

Carl Beauchemin: We already knew how to rig in Maya. But as we wanted to realise the project in Softimage – the programme we mainly worked with after our studies – we had to learn everything from scratch. So the first character rig was quite a challenge. It took us a month to finalise it. But after that it was just a matter of repeating the same steps. We made sure that the same parts of the rigs had the same names for all the characters. This allowed us to transfer the animation of one character to another, which sped up production considerably. This mainly concerned movements such as running, cheering or sowing. To simplify the process of animating faces and fingers, we had Visual Panels at our disposal. This allowed us to select animation controllers quickly and intuitively. But our biggest challenge was the bridge. It consisted of over 70 duplicated individual parts, so the rigging had to be well thought out right from the start.

DP: Which ZBrush tools were useful to you?

Carl Beauchemin: We used the ClayTubes brush the most, which is great for refining details, especially when used in conjunction with the Smooth brush. The brush also behaves very similarly to the one we used in Photoshop to paint our textures. Other useful brushes I can mention are Pinch and Slash3, which we used to paint all the crevices and details of the rock face or the folds in the clothing. The Decimation Master also turned out to be a lifesaver. We often had to create high-resolution set elements in close-up at the last minute. This plugin helped us to export meshes that had a lot of detail but could still be rendered quickly. ZAppLink also proved useful in our painting process, as it allows you to seamlessly integrate image editing software – in our case Photoshop – into ZBrush.

DP: How did the work with Sony Vegas go?

Carl Beauchemin: This editing software was used for the entire editing process. We updated the edit almost every day. That was brilliant for keeping an overview. We always knew exactly what had already been done and what hadn’t. We stacked many video tracks on top of each other: 2D animatic, film references, animation captures and final renders. When we added a new clip, we could play the whole sequence to make sure everything ran smoothly.

DP: Which renderer did you use?

Carl Beauchemin: Since we didn’t have the resources to render complex shaders and lighting, we used basic shaders, mostly surface shaders and lamberts. All the details were in the painted textures, so we didn’t need anything more complex than that. We even faked the subsurface scattering in some textures, such as the ears of the characters. Rendering was done in Mental Ray, the default renderer in Softimage. The renderer did a good job and produced our frames at a decent speed.

DP: How long did the rendering take?

Carl Beauchemin: We rendered frames every night and at weekends – for over a year. I can’t tell you the exact number of hours, but it must have totalled around 15,000. We couldn’t use the services of a render farm for budgetary reasons.

DP: How did Kickstarter help you in the end?

Carl Beauchemin: This crowdfunding platform was our last resort – and our best decision during the entire project. We ran out of money in mid-2013 and were looking for ways to pay our musicians and sound designer. This meant that a campaign, wherever it was launched, simply had to work. One crucial point was that we already had followers. Not many, but just enough to reach a few hundred people who shared our Kickstarter page with their friends after the launch. One of our goals right from the start was to build a fanbase. To do this, we set up a production blog and published concept art, insider information and lots of tips and tricks that we had learnt from our work there every fortnight. At the same time, we filled our Facebook page and continually posted in various CG forums. After a year and a half, we had quite a decent number of followers. But it took a long time and a lot of effort to build up this fanbase.

DP: But at that point you were already able to show your first results.

Carl Beauchemin: That’s right, we were already very far along in the film production. So, fortunately, we were not only able to show a lot of shots, but also cut a trailer that caught people’s attention. It was also very obvious that we had already invested a lot of time, effort and money in this project. So the message was not: “Give us money so that we can realise our dream”. Rather, it came across that we had already done everything we could on our own. Now it was just about that little push we needed to complete the project. I think this approach touched people and helped make this campaign such a big success: With 711 backers, we raised a whopping 24,155 Canadian dollars instead of the planned 5,000.

DP: Looking back, would you do anything differently?

Carl Beauchemin: No, I don’t think so. The biggest problem for us was that we misjudged the time. It took us two years to produce the album instead of one year as planned. Looking back, there was no other way to achieve the quality we wanted. Basically, our naivety and enthusiasm were an advantage. Because if we had known beforehand that it would take two years, we might have waited a few years until we had more money together. One of us would probably have changed our minds and decided to call the whole thing off. “Le Gouffre” probably wouldn’t have turned out like this if we had waited longer.

DP: What’s next for you?

Carl Beauchemin: The film has finished its festival run and is now online. It has been incredibly well received and we couldn’t be happier. From the beginning, our goal was to get the attention of people working in the film industry. We wanted to show what we can do as a team. We hope that this project will lead to new partnerships. As Lightning Boy Studio, we want to develop and direct projects. However, we are keen to work with other studios that take on the administrative parts such as renting space and hiring staff. We also all have our own jobs: after completing “Le Gouffre”, David and his wife founded “MrCuddington”(mrcuddington.com) and now create illustrations for board games from home. I now work as a 3D artist at Pascal Blais Studio(www.pascalblais.com), which specialises in animations for commercials, and Thomas works as a director and VFX artist at Hibernum Creations(www.hibernum.com), a mobile games company.