And it turns out that a Film Academy graduate, who we still know from Animago 2014, was the executive producer for Pixomondo – Paolo Tamburrino. He is currently in charge of virtual production and VFX for Star Trek at Pixomondo. He is the go-to person for technically challenging projects and client engagements. With over 15 years of experience in animation and visual effects, he has been involved in many varied and award-winning projects.

Paolo is a graduate of Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg, where his graduation short film “Wrapped” was honoured with a VES Award and an Animago for Best Newcomer Production(bit.ly/wrapped_filmaka).

Since then he has worked in Asia, Australia, Europe and North America on projects such as Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Foundation, The 100, Upload and numerous commercials. Paolo is currently a board member of the Visual Effects Society in Toronto, a board advisor to the Realtime Conference and a member of the Programme Advisory Committee for Virtual Production at Humber College.

Paolo is at Pixomondo – which we all know. An Oscar, Emmy and VES award winning team for

Virtual production, visualisation and of course VFX. PXO is now a world leader in on-set virtual production and virtual production services, providing a network of the most advanced LED volumes, supported by an experienced virtual art department, resilient on-set supervisors and volume control teams for excellent in-camera VFX (ICVFX).

DP: Hello Paolo! How did you get into the Star Trek universe in the first place?

Paolo Tamburrino: The transporter room is on the left behind the coffee machine (laughs). Joking aside: Star Trek and Pixomondo have a long-standing partnership. In addition to Picard and the “Short Treks” (stand-alone short films for Discovery), PXO has been a visual effects companion in the ST universe since the first season of Discovery. In addition to multiple nominations including Emmy and VES Awards, PXO’s Star Trek team reached a first peak when we were nominated for an Oscar for Best Visual Effects in a Feature Film with J.J. Abrams’ “Star Trek Into Darkness”. To build on this, we were brought on board with the fourth season of Discovery and the very first script lines of “Strange New Worlds” – and created a special collaboration.

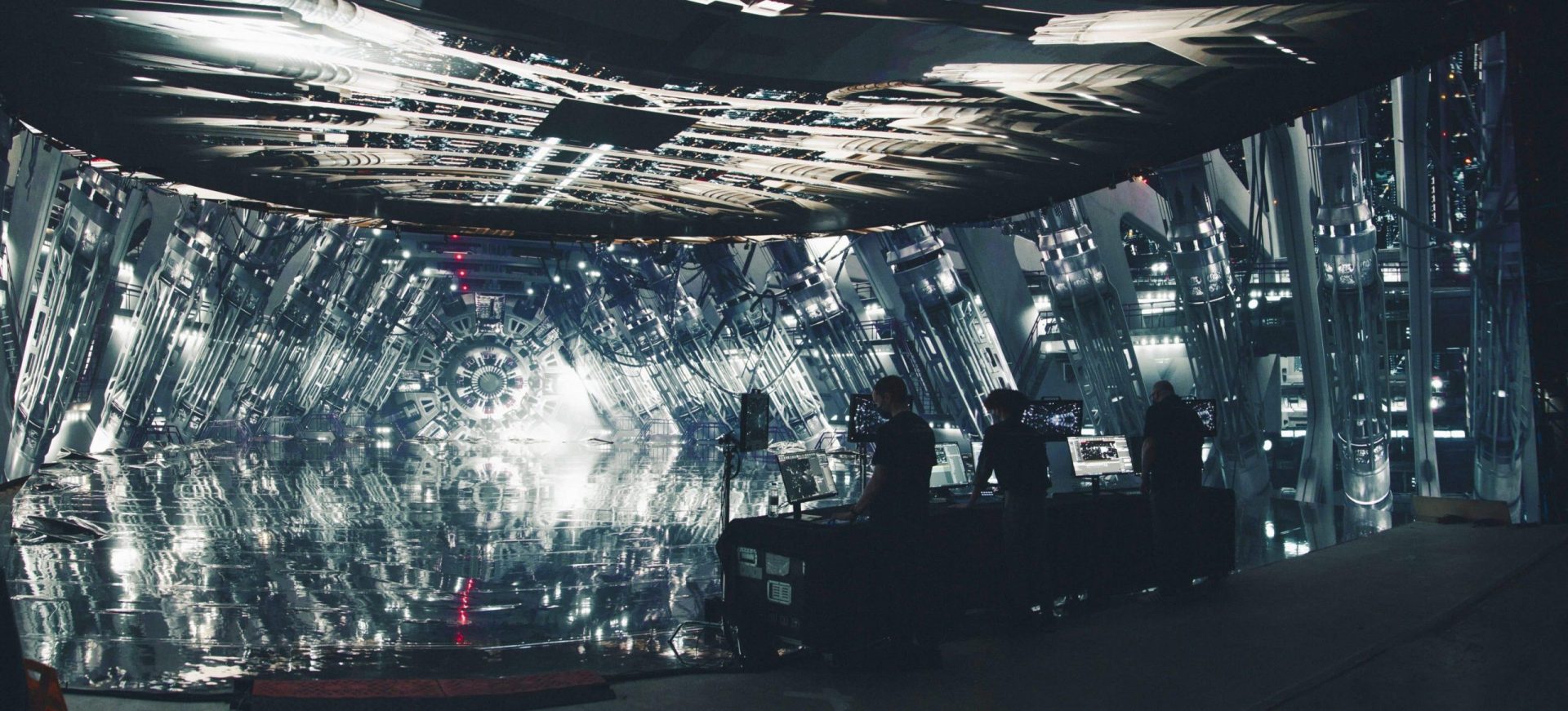

For the non-Trekkies: both series are set in different worlds and times. While Discovery is already visually established, Strange New Worlds pays homage to the original Star Trek from the late 1960s. The look has to be so in keeping with the original and “our” near future (It’s set roughly in the year 2259 of our era), while Discovery can appear much more futuristic. While we were starting to think about the production, the pandemic inappropriately (or appropriately) hit in 2020 and we set about reinventing the holodeck.

Because the pandemic really challenged us – like all film studios, we had to keep productions going. While the world holds its breath, bakes banana bread and puts all shows on hold (or cancels them altogether), we have made something of it: converting the VFX-proven production to the (at the time still distant) vision of real-time rendering in a virtual production! To be more precise: in-camera visual effects (ICVFX). This didn’t happen overnight – and fortunately Pixomondo had already invested over the previous years in addition to its core business of traditional VFXs and built up the necessary expertise.

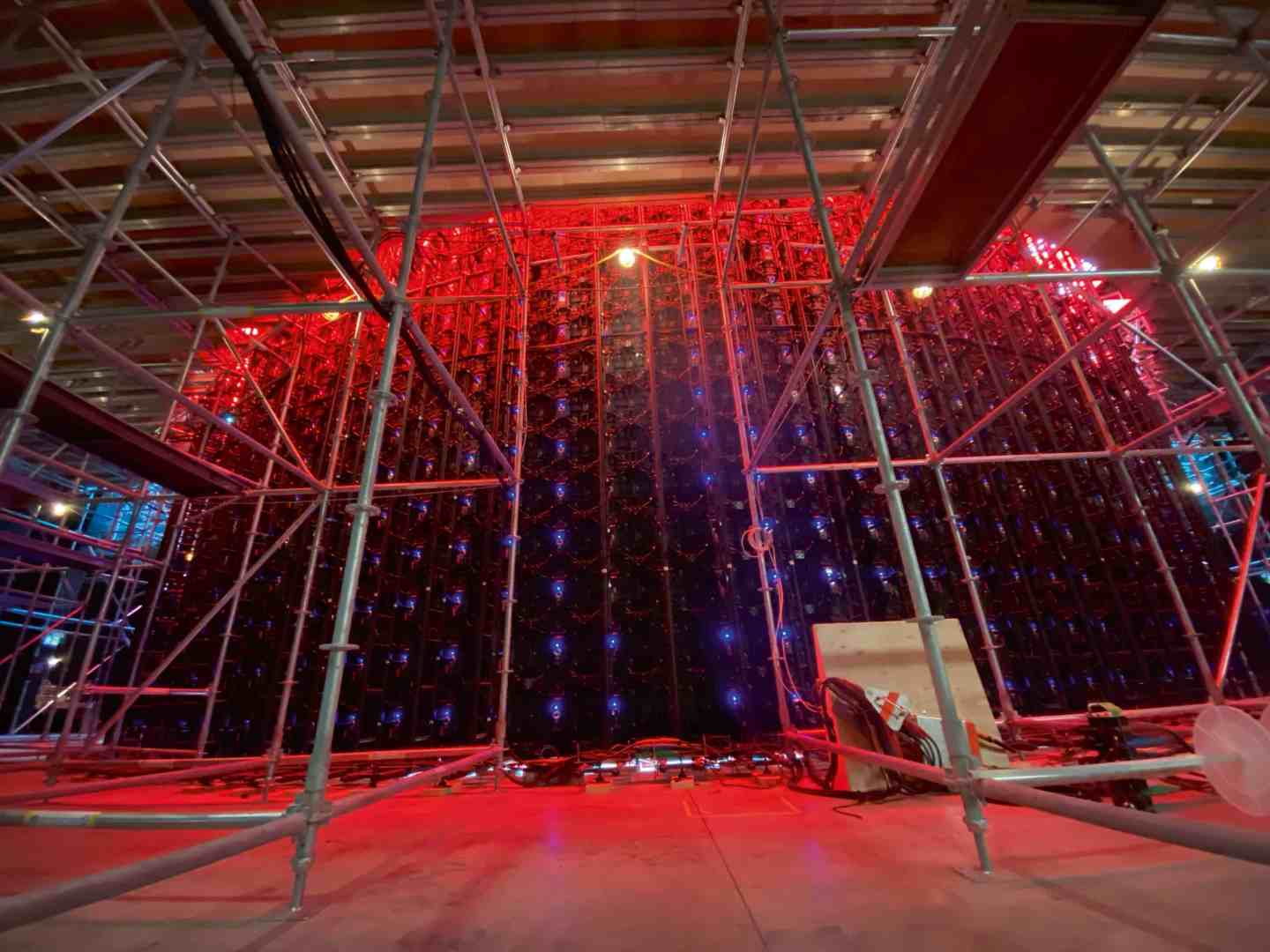

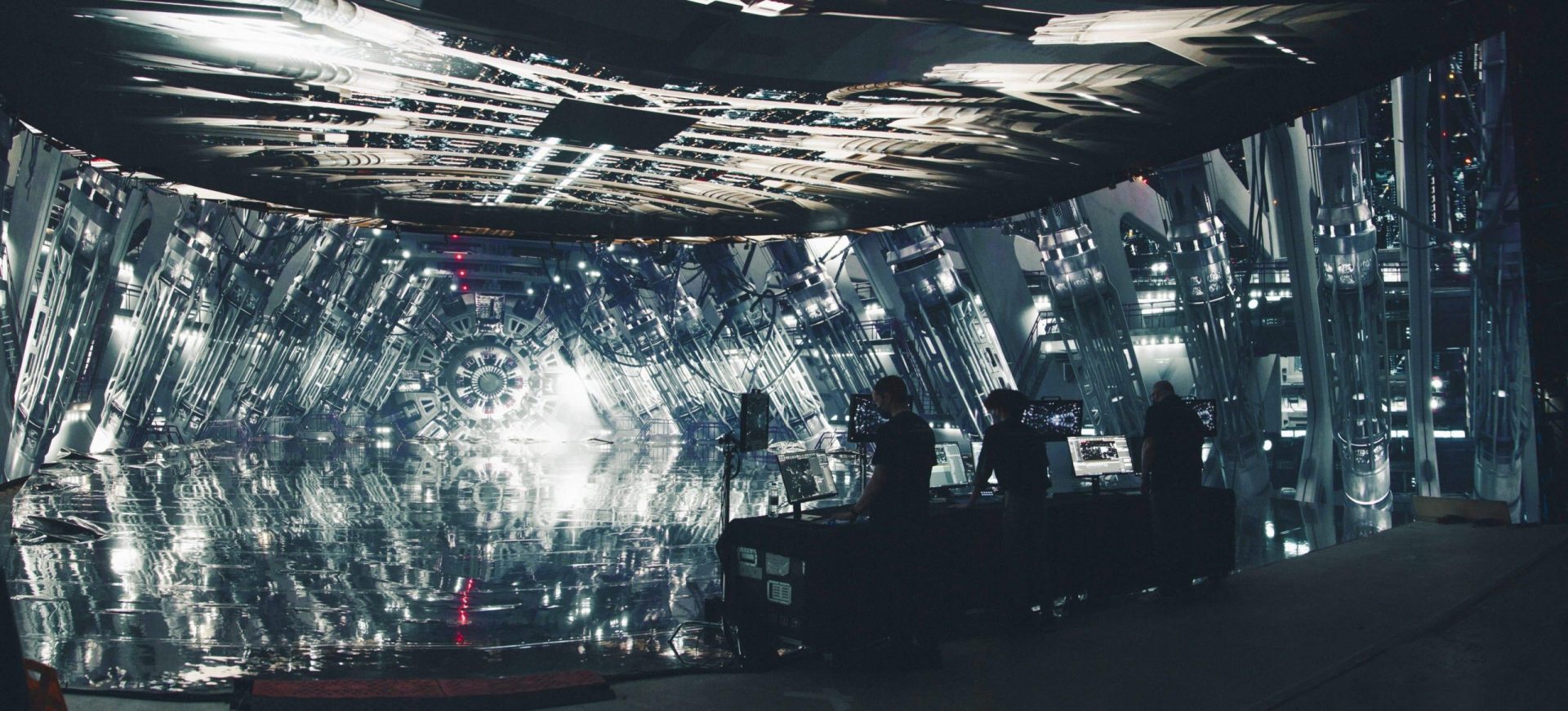

Being awarded the contract to build the first LED volume in Canada and exclusively create the worlds for it was the start of one of the biggest adventures in our history – and at the same time, it set the stage to realise Discovery and Strange New Worlds under the highest health and safety measures. And yes, we always wore masks on set for all shoots.

In addition to the ongoing pandemic, supply bottlenecks and stranded container ships in the canal, the LED volume – also known as the “holodeck” in the Star Trek family – had to be ready for operation within a few months. Mahmoud Rahnama (CIO-CCO) and Josh Kerekes (Head of Virtual Production) were in charge of the planning and execution of the LED volume construction and the associated infrastructure

tual Production).

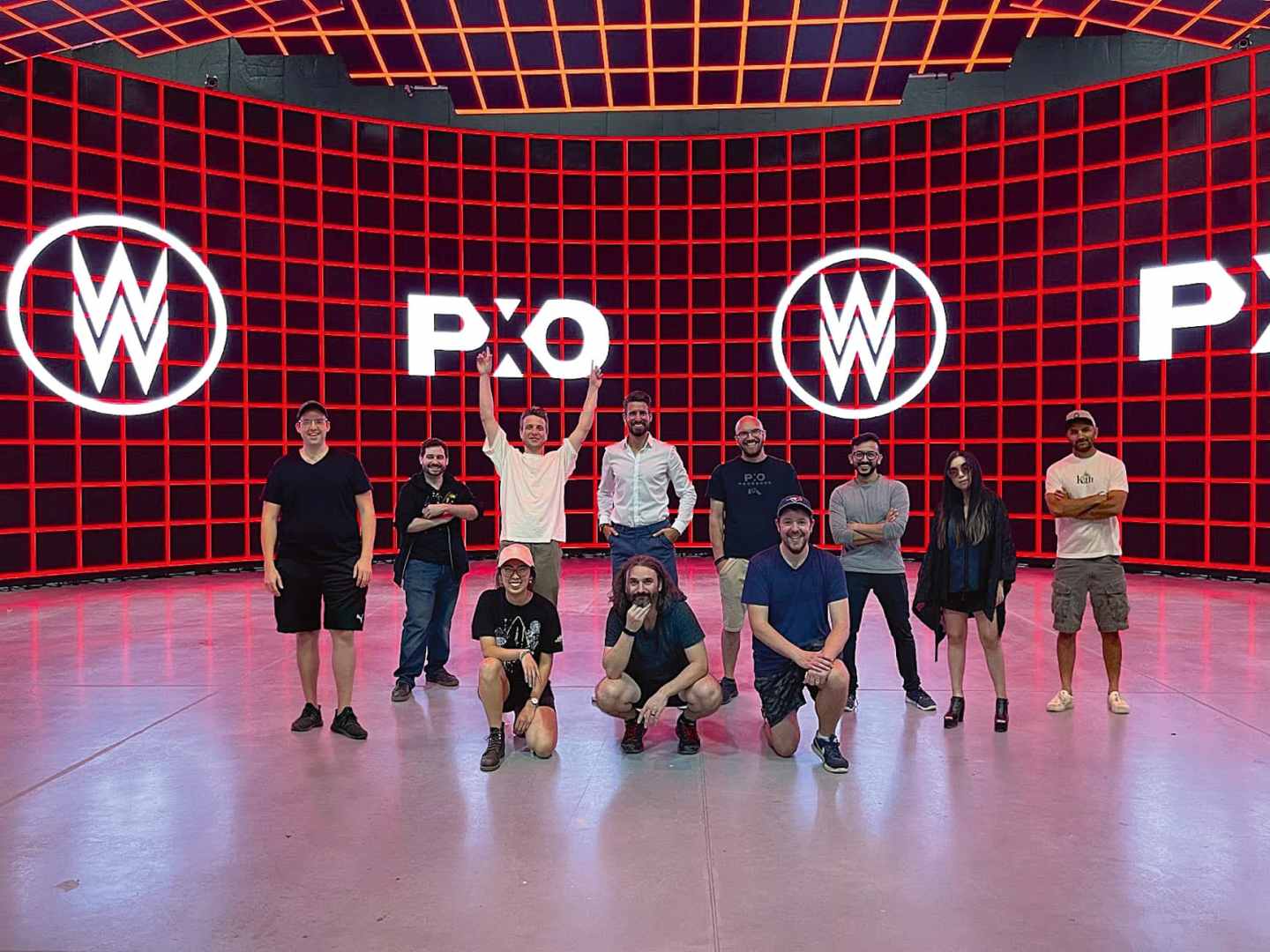

Front row from left: Linda Vo, Owen Deveney, Matthew Pella

While the LED volume slowly began to take shape over the Christmas holidays, my focus was primarily on developing and defining workflows and processes, building the team and producing all the virtual worlds and associated visual effects for Star Trek: Strange New Worlds. Together with our in-house VFX and VP supervisor, Nathaniel Larouche(nathaniellarouche.com), who oversees both Discovery Season Four and Strange New Worlds, we acted as external partners to the studio’s in-house VFX teams, overseeing the script development and conceptualisation phase for the creation of the virtual worlds through to shooting and post-production.

Complex planning and risk assessment was crucial! There are several reasons for this – the most important is the certainty that the worlds will perform visually and technically at the highest level on the day of filming. In contrast to VFX, virtual production (ICVFX) cannot afford to make any mistakes. A delayed, interrupted or even cancelled shooting day can have fatal consequences.

In order to minimise the risk, we made sure that all departments were involved in the creative process and that procedures were understood. In addition to the use of VR and remote reviews via Zoom, we introduced interactive stage reviews and were actively involved in the production and shoot planning in an advisory capacity.

DP: And what does that mean?

Paolo Tamburrino: We had to find a language that could be used to communicate the complex processes and technical possibilities and limitations of virtual production (ICVFX). A corresponding amount of development went into the creation and correct adaptation of the production, art department and camera/lighting department. To this end, PXO developed show-specific technologies to integrate virtual production processes “more naturally” into the established film environment, including the integration of DMX (which was not yet available at the time) in order to film almost seamlessly with several DoPs and directors in an LED volume.

In addition to the technically complex processes and approvals for the filming of the respective worlds, we introduced the development of a hybrid model for digital assets and thus took the step towards end-to-end utilisation. While planning the virtual worlds, we were aware that there would be traditional set extensions, establishers and dynamic FullCG shots in addition to ICVFX – and we had to take this into account for digital assets with Unreal Engine and traditional rendering. Due to the ongoing pandemic and local restrictions, both shows were produced in alternating shots.

The even tighter shooting schedule and maximised number of worlds was only possible thanks to the close collaboration between our core virtual production team (led by Asad Manzoor, Head of VP Content) and our amazing stage crew. Fortunately, at peak times we were able to call on the expertise of our colleagues in Germany and complete one of the first more complex worlds in Strange New Worlds within the given time frame.

DP: And what did you do there?

Paolo Tamburrino: Simply put, in just under 12 instructive months and 20 unique worlds later, we had not only successfully written the fourth season of Discovery and the first chapter of Strange New Worlds, but also created a new (and I think exceptional) team between the studio and the VFX house.

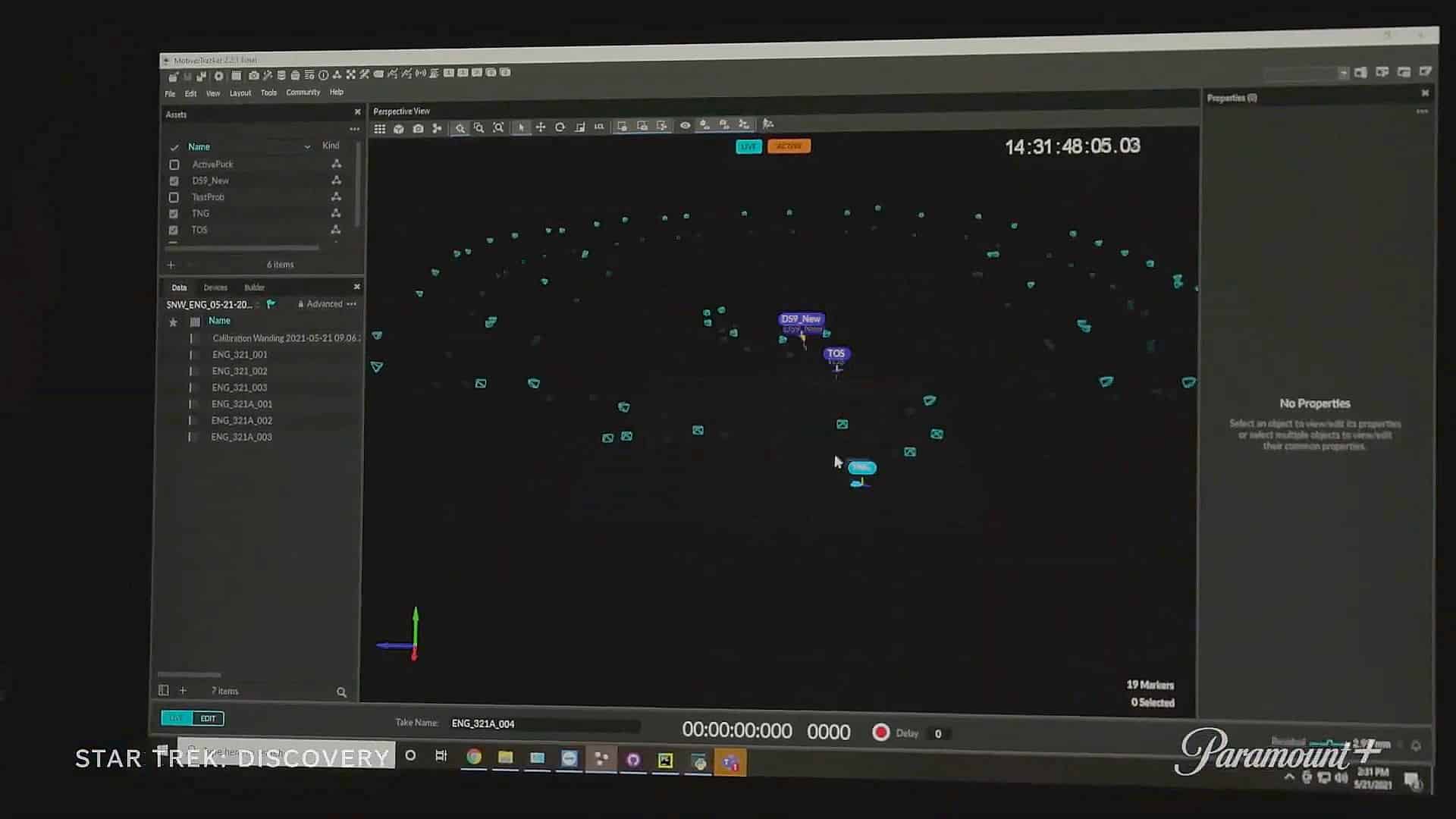

But let’s start from the beginning: we not only created twenty virtual worlds, but also optimised the shoot visually and technically with the entire Pixomondo team – so in addition to the operational tasks at the brainbar (including the calibration of motion capturing, data synchronisation, integration of virtual and physical lights and SFX, as well as all other functions of the LED volume), a team dealt with the “blending” between the digital and real set a few days before the shoot.

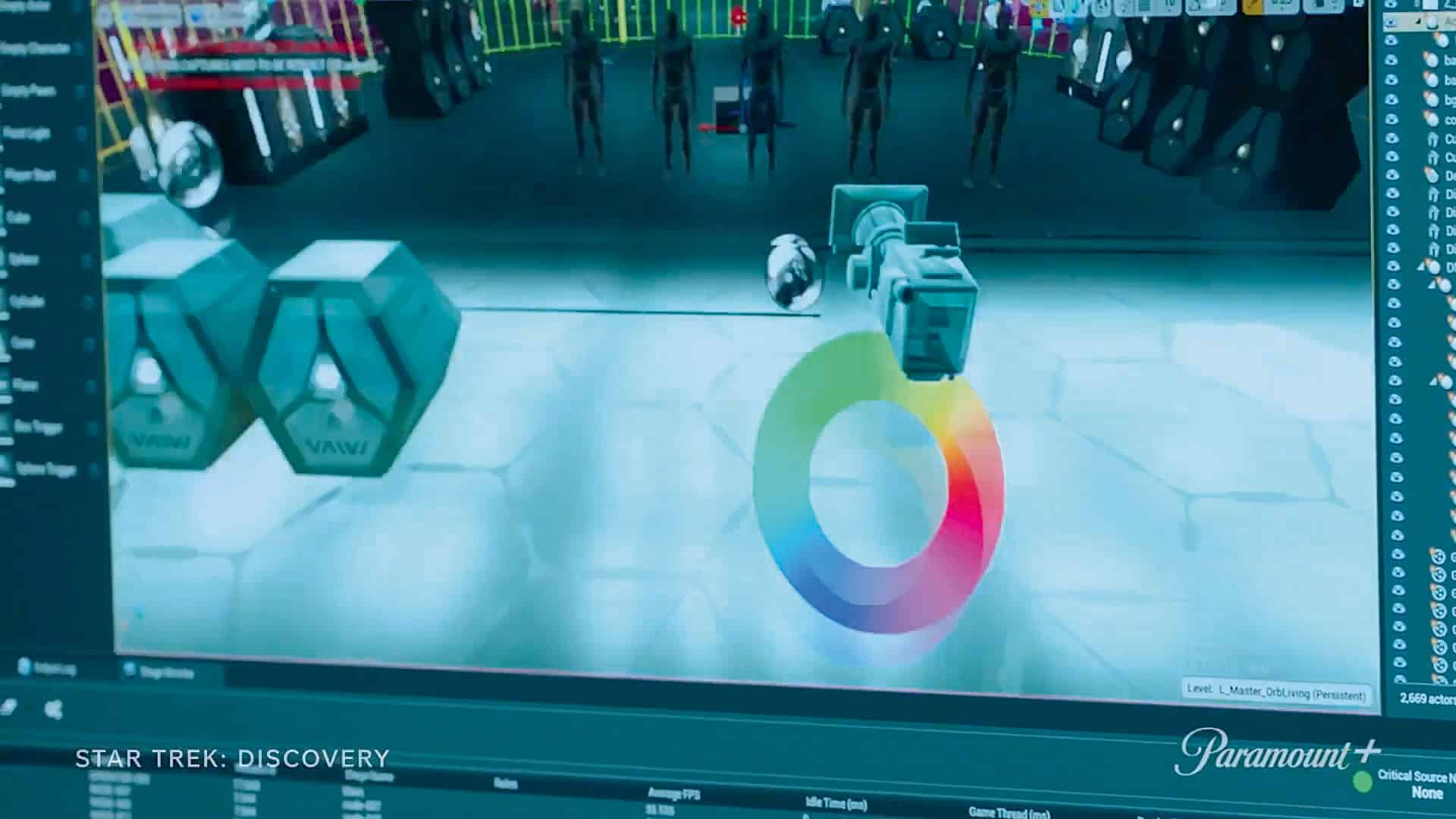

This means pragmatically: minor layout corrections, the adjustment of dynamic lights, the setting of animation cues and colour corrections in the Unreal Engine (CCRs) are particularly important here – because during the “Blend Day”, the set, virtual world, camera, lenses and LUT are brought together for the first time, and the interfaces and details can be seen “in real life”. The decisive factor here is always the result captured by the camera.

Blend day is probably the most stressful and creative phase for our stage crew. The final touches are added in close collaboration with the DoP, the lighting department and the director. And while the set has two more days of rest, we optimise the performance and carry out stress tests.

Matthew Swanton, our Lead UE Technical Artist, says: ‘On stage, the tracking markers are always on the camera, and not on the performers. This enables us to render a correctly equalised image on the LED wall for the camera perspective. To do this, we have to ensure that we can always deliver 24 frames per second during the optimisation and stress test phase. So we look at both the usual problem areas that can occur in setups and that we can also operate two cameras onset at any time. We do use large workstations with extreme power, but… It’s never enough.

Furthermore, such technical blockers are essential to solve unforeseen technical problems, as some of the things we need to realise such a virtual production are not yet compatible with the Unreal Engine. In this important final phase, we can find possible problems and solutions, and at the same time ensure that the shoot is successful.

DP: How many cameras are you using on set?

Paolo Tamburrino: We normally film with two, maximum three cameras. At the beginning, we decide which of the two cameras has priority, as both are accompanied by a “Frustum” rendered from the Unreal Engine on the LED wall. To avoid background overlaps on both cameras, one is selected as the hero cam so that if it is unavoidable to have both Frustums in one take, only the background on the second camera needs to be partially replaced.

The third camera, on the other hand, is used to record the acting performance and the captured light/reflections, where it is already communicated in advance that the virtual background must be completely replaced in post. If you want to know more about this, just google “Frustum”.

DP: So isn’t the second camera outside the LED volume?

Paolo Tamburrino: The distance varies. Normally we can have two cameras in one volume without obscuring the sensors. To do this, we sometimes have special setups and mobile units of tracking cameras that we use to track through elements and/or out of the volume for particularly large and long crane sequences. These are things that we play through on Blend Day, even if it looks silly to run around outside the stage with cameras and check the sensors.

Finally, we attended the shoot – together with the film studio’s VFX team – and made sure that all systems, including motion capturing, worked perfectly and that it was possible to switch between different times of day, lighting scenarios or even worlds on the same day of shooting.

The great thing about VPs is the creative freedom they offer during filming – but they need to be well prepared! The final touches are made in post-production, where we partially or completely replaced backgrounds where necessary due to seams (caused by construction-related gaps and motion tracking sensors between the wall and ceiling), retouched stunt or lighting rigs or added more complex animations. Otherwise, the worlds were prepared for VFX to create dynamic flights and FullCG shots – the approximate ratio here was 80:20 ICVFX shots versus prepared shots.

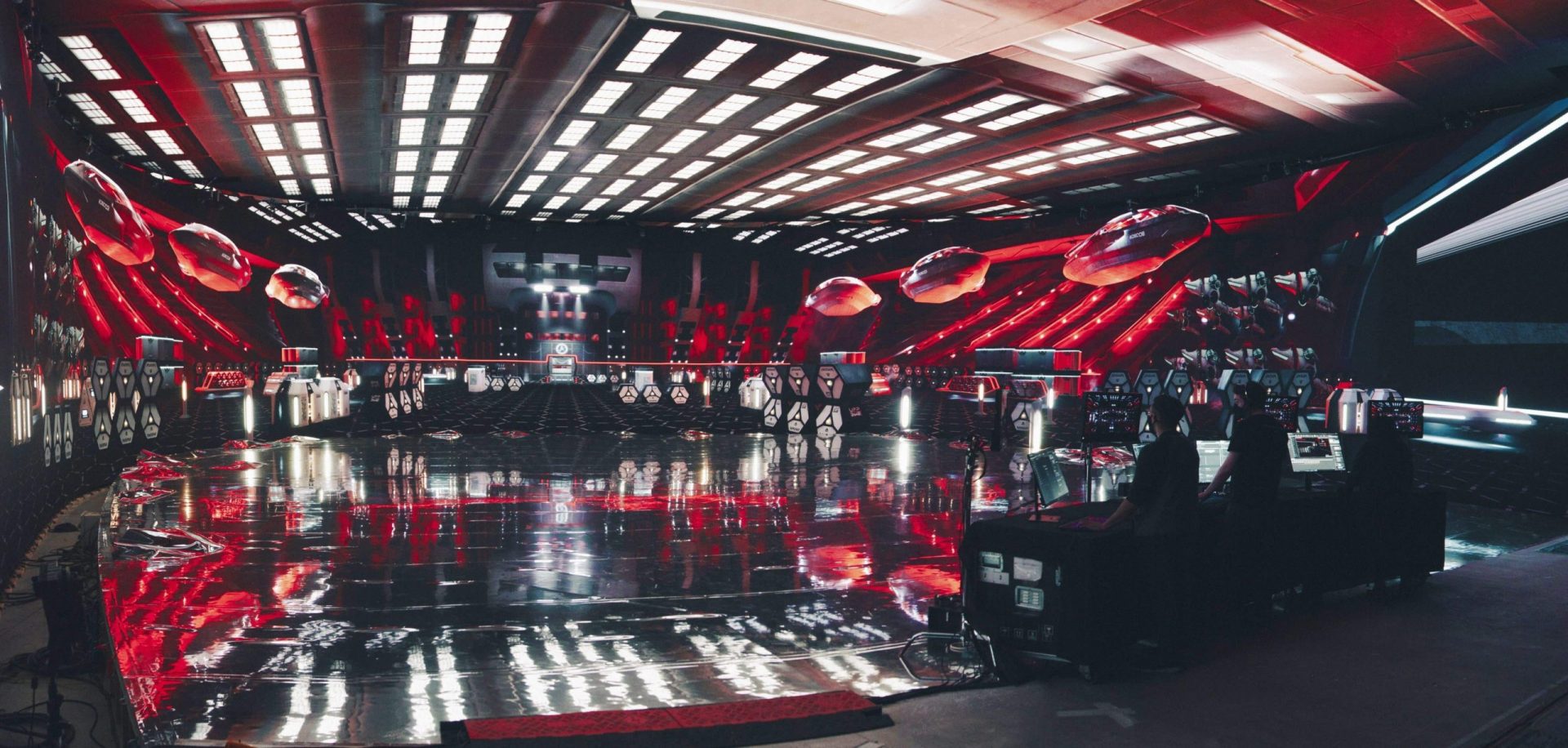

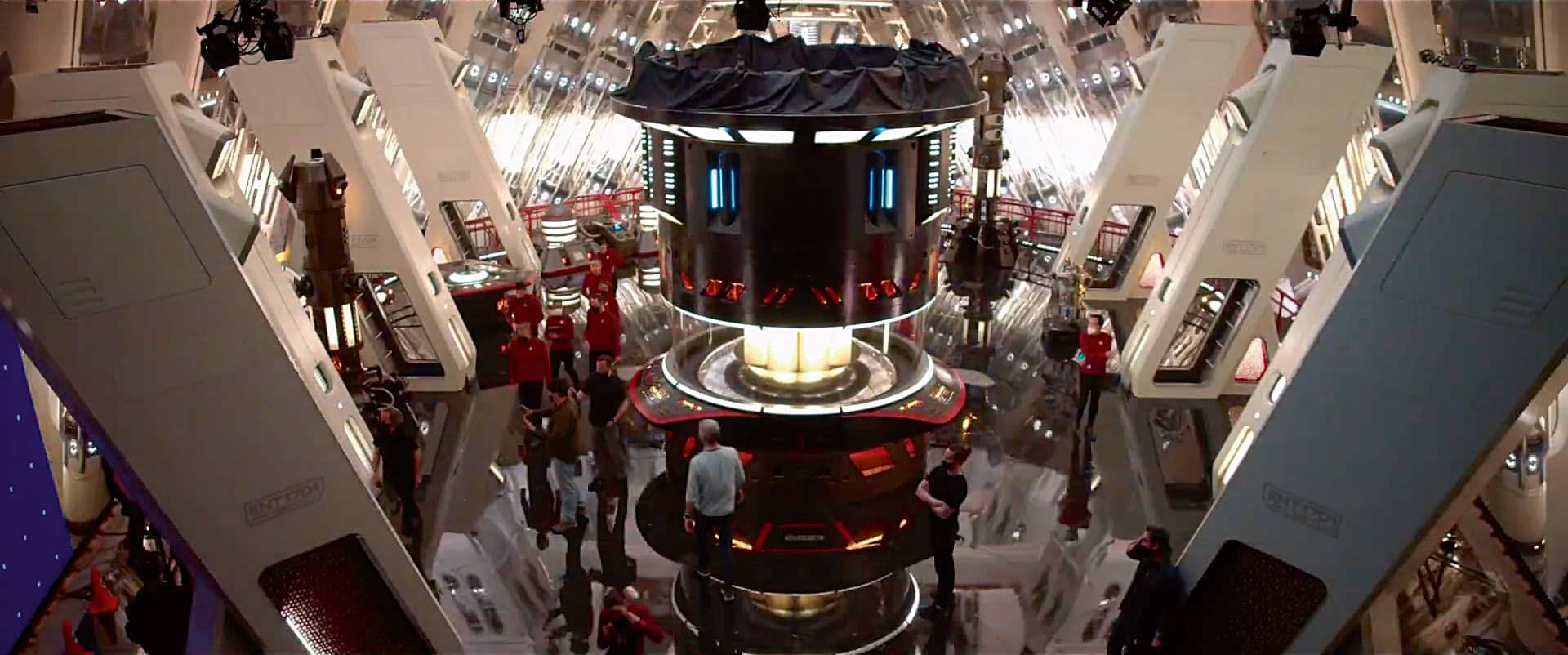

DP: What do the stages look like?

Paolo Tamburrino: Pixomondo currently operates three customised LED volumes. Two of them are located in Toronto and one in Vancouver. Toronto (YTO01) is Canada’s first LED volume and Star Trek’s primary stage, while the second stage is modular and is used for advertising projects and research and development, among other things.

Vancouver, on the other hand, was made even larger for a multi-vendor production and was honoured with an entry in the Guinness Book of Records. If you want to know more, you can find more information at Whites here – whites.com/virtual-production. And anyone who doesn’t believe how big the LED stages are will unfortunately have to rely on the Guinness Book of Records (laughs).

| Here are a few key figures | ||

| Toronto (YTO01) | Toronto (YTO02) | Vancouver (YVR01) |

| Stage: 2090 m2 | Stage: 1495 m2 | Stage: 2045 m2 |

| LED volume: 510 m2 | LED volume: 185 m2 | LED volume: 650 m2 |

| Shape: Horseshoe (22 m diagonal) | Shape: Semi-circle (19 m diagonal) | Shape: Circle (24.25 m diagonal, 310 degrees) |

| Ceiling height: 7.25 m | Ceiling height: 6.2 m (individually motorised sections) | Ceiling height: 8.5 m |

| Wall panels: 1800, ROE LED-BP2 | Wall panels: 720, ROE LED-BP2 | Wall panels: 2500, ROE LED-BP2 |

| Ceiling panels: 650, ROE LED-CB5S | Ceiling panels: 175, ROE LED-CB5S | Ceiling panels: 760, ROE LED-CB5S |

| Projects: Star Trek: Discovery, Star Trek: Strange New Worlds (Paramount ) | Projects: Beacon 23 (Spectrum), Rabbit Hole (Paramount ), In The Dark (CBS Studios), McCafe, World Cup, Genesis, TD Wealth | Projects: Avatar: The Last Airbender (Netflix) |

DP: Suppose you could remodel the stage: What would you change?

Paolo Tamburrino: An espresso machine! There’s enough cold filter coffee on every set… But apart from this remodelling: If we look at the perspective of what we should build into “the stage”, then we have to raise the bar in terms of quality AND storytelling – “we” as the “Star Trek team” and as Pixomondo. To this end, I would like to see the use of machine learning, which can help with physical challenges such as the calculation of virtual depth of field. Outsourcing the repetitive steps is an avoidable source of error on long shooting days.

And after the depth of field calculation: there are dozens of things that can be wonderfully outsourced here with machine learning after a few shows (and the corresponding training data) in order to get much more “in camera” into the “ICVFX” – and of course to have to clean up less in post.

Physically speaking, I would like to see higher walls, which are usually limited by the physical size of soundstages. Higher walls would allow us to show more of the world – for example, to look interactively into the sky or from the top of the virtual world. Currently, the ceiling is mainly designed to illuminate and provide reflections – accordingly, we use low-resolution LED panels, while the actual world is available in high resolution with up to 360 degrees. Added to this is the expenditure of resources and costs in post, which could be avoided – because in addition to cost-cutting measures, we ultimately want to provide the artists with creatively challenging tasks.

When we talk about the VP stage, I see newer LED panels in the future that are not only more true to colour, but also more flexible (bendable) and usable outdoors. There are some initial products, and hopefully something exciting soon – if smartphones already have foldable screens, it must be possible!

Speaking of exciting: not every show needs an LED volume. I can definitely imagine modular or floating configurations outside a building or soundstage. This would not only make the application more cost-efficient, but also more flexible, e.g. for set extensions.

Just imagine adding elements to the classic Star Trek episodes in the TMZ – a mobile set-up with a screen in front, and tracking and projection equipment in the background. “ZACK, we’ve got an alien standing around!” or at least an alien cactus, or with a few panels an alien city in the background. It would also be exciting to have an advanced motion capturing system that allows you to move between worlds. At the moment we are still tied to a fixed location. What if we could move seamlessly through different worlds with the camera?

Apart from hydraulic platforms and other constructions within the LED volume, there could be mouldable or mobile floor panels. Complex escape routes are still difficult at the moment. However, I think that we should talk to the stage builders in classical theatre in the near future – or with our colleagues from the event industry!

There are obviously other things that I can imagine and would like to see. Basically, all applications should serve to tell the story and associated world in a more interactive and real way and give the actors the opportunity to immerse themselves in their worlds even more deeply than before – but I hardly need to say that (laughs).

DP: And what kind of team does it take to populate a new galaxy?

Paolo Tamburrino: Virtual production, primarily in combination with ICVFX rendered in real time, is completely new territory, especially on this scale! The roles are still in the discovery phase and vary from company to company, so they are not standardised across the industry. That’s how it is for us at the moment: Our PXO-internal Virtual Production team, which is responsible for the holodeck (LED volume) and virtual worlds as well as VFX shots, consists of three core groups: Virtual Art Department (VAD), Stage Operation (The “Brainbar”), and traditional VFX Departments. There are also R&D, Production and other departments.

VAD forms the interface between the traditional Art Department and Virtual Production, and is a fixed and important component during the script and conception phase. The earlier this department or team is involved as part of the overall process, the more efficient the collaboration will be. The virtual art department works closely with the art department, scriptwriters and, if available, the director and camera department.

VAD can contribute to the conception by researching and designing the worlds, as well as creating mood boards and key art, which gives all departments the opportunity to form a clear understanding of what the actual world or set will look like well before shooting begins. Furthermore, in the first phase, the VAD team offers the opportunity to create a prototype of the world, which makes it possible to estimate the dimensions of the LED volume at an early stage and correct them if necessary, while at the same time blocking the first look and lighting scenarios together with the DoPs. Previously, this was only possible for the director through Previs. VAD allows for natural and interdisciplinary collaboration between all departments.

The team consists of a project leading art director, VAD supervisor(s), VAD concept artist, generalists and lighters (specialised in Epic’s Unreal Engine) as well as technical artists, some of whom come from the video game or development sector. If you are interested and want to be part of creating the industry standard – check out pixomondo.com/careers! And if you already have expertise in animation, games or VFX, why not take a look at the Virtual Production Academy?

DP: And the stage team?

Paolo Tamburrino: Our stage team is a mixture of the event and film sector, which is occasionally supplemented by hybrid roles for specialised Unreal operators. It can be compared to the production of advertising films, where there are dedicated flame operators and colourists for the “online”. We operate in a similar way at the brainbar.

During the acceptance tests and the “Blend Day”, dynamic lighting adjustments, DMX, playback, scene optimisations, colour corrections using CCRs (Unreal Color Correction Region) and various other tasks are carried out in real time with the customer at the stage. In addition, our team is available for prop and set scanning using LIDAR or photogrammetry, which is processed internally for virtual production and/or VFX. The work is completed by our established VFX departments – primarily Assets, CGFX and DMP. And all under one roof!

DP: How do the teams coordinate?

Paolo Tamburrino: Virtual Production allowed us to move into other dimensions with the latest generations of cloud solutions, especially during the pandemic, and to involve talent worldwide. Entire worlds could be created globally and virtually through Perforce and Teradici, among others, despite ongoing lockdowns and travel restrictions.

But let’s be honest: virtual production, primarily ICVFX, is still a rare segment that cannot simply be created from VFX or games. The conception and production of the worlds as well as the execution on stage and possible post-VFX shots require a broad range of expertise and a willingness to learn. Creatively and in production – all areas in which experienced personnel are in short supply and existing talent is currently “unicorns”.

DP: And what is the Virtual Production Academy all about?

Paolo Tamburrino: We at Pixomondo have recognised the acute need for personnel and the challenges it poses and, in addition to internal training (which you always do as a serious VFX studio anyway), we have created the Virtual Production Academy(VPA). Together with partners such as Epic as well as established conferences, we as a team and company try to share our knowledge in order to set an industry standard and train the next generation of artists and production professionals.

The VPA not only supports artists, but also filmmakers who want to familiarise themselves with the technology and techniques before starting production and integrate them into their project. So, anyone interested in VP should pay a visit! virtualproductionacademy.com

DP: Since Pixomondo has been in the Discovery universe since season 1, what assets have you been able to “take with you”?

Paolo Tamburrino: While the production of the VFX assets from previous seasons dates back several years and was based on a different pipeline, new industry standards such as USD,

Arnold and Unreal Engine allow us to build an end-to-end pipeline. So we have that in mind – but there have been some fundamental changes to formats in recent years. Basically, we want to reuse existing assets, but these still require additional effort to conform with new rendering, among other things.

In addition, there is the conversion for real-time rendering in Unreal. It is currently not quite possible to translate traditional VFX assets 1:1 into Unreal. Added to this is the increased complexity of utilisation within an LED volume. The assets need multiple resolutions and methodologies in order to be displayed with high quality and performance in different camera settings and movements in both full frame and frustum. Sounds strange, but a simple alembic cache is not enough.

Strange New Worlds has already set the first milestone in switching from the traditional VFX asset workflow to a hybrid model in order to focus entirely on real-time rendering in the future. Ideally, this will allow us to build a complete and dynamic asset library. This library will enable us (if everything works out) to use assets both on an LED volume and in the “traditional” shot work.

In addition to consistent quality and ensuring performance on an LED wall, it also saves resources – and in the “concept art phase” we have completely different possibilities to “poach” in the asset library together with our customer, for example by using rotated elements in landscapes – at some point there will also be a kind of “kit bashing” in the LED volume!

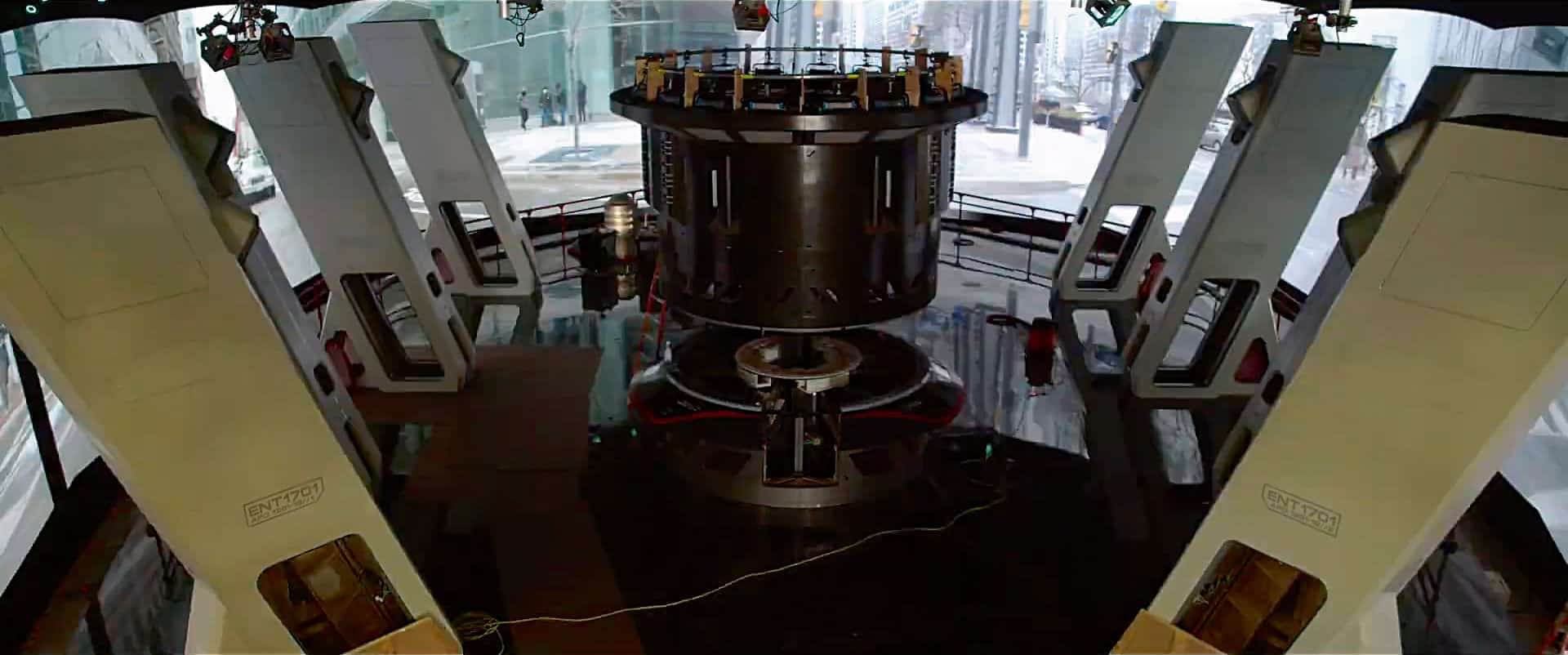

DP: How do the possibilities of a large stage influence the set design?

Paolo Tamburrino: The architecture of an LED volume can of course influence the set design. In order to avoid (still) existing technical limitations, e.g. of LED panels, special technical constructions can lead to the set having to adapt to the architecture. However, the atypical format can usually be broken up by pre-planning and the use of props in the foreground – or used much more extensively with French reverse (two or more actors stand at the same point, but the choice of background makes them appear to be standing next to each other. – Editor’s note).

The “horseshoe” format is currently one of the most common configurations – but not the only possible stage design. There are now many different scenarios and integrations of LED walls. In general, the design of the LED wall is discussed in advance with the various groups and customised so that the worlds and sets presented can be implemented in full. If you get involved and think along, the use of virtual production can also have a constructive influence on the set design (depending on the time frame and complexity of the worlds, of course) and clearly differentiate it from previously seen sets.

One example of this is the “Enterprise Saucer Section”, which can be seen in Strange New Worlds, Episode 105. Here, PXO’s Virtual Art Department provided an optimised section of the Enterprise as a 3D model to the Art Department, which used 3D printing and manual labour to produce a real prop on which the protagonists could perform on an almost seamless real-digital spaceship. (Number One and La’an signing the hull segment. You know what happens next! – Editor’s note)

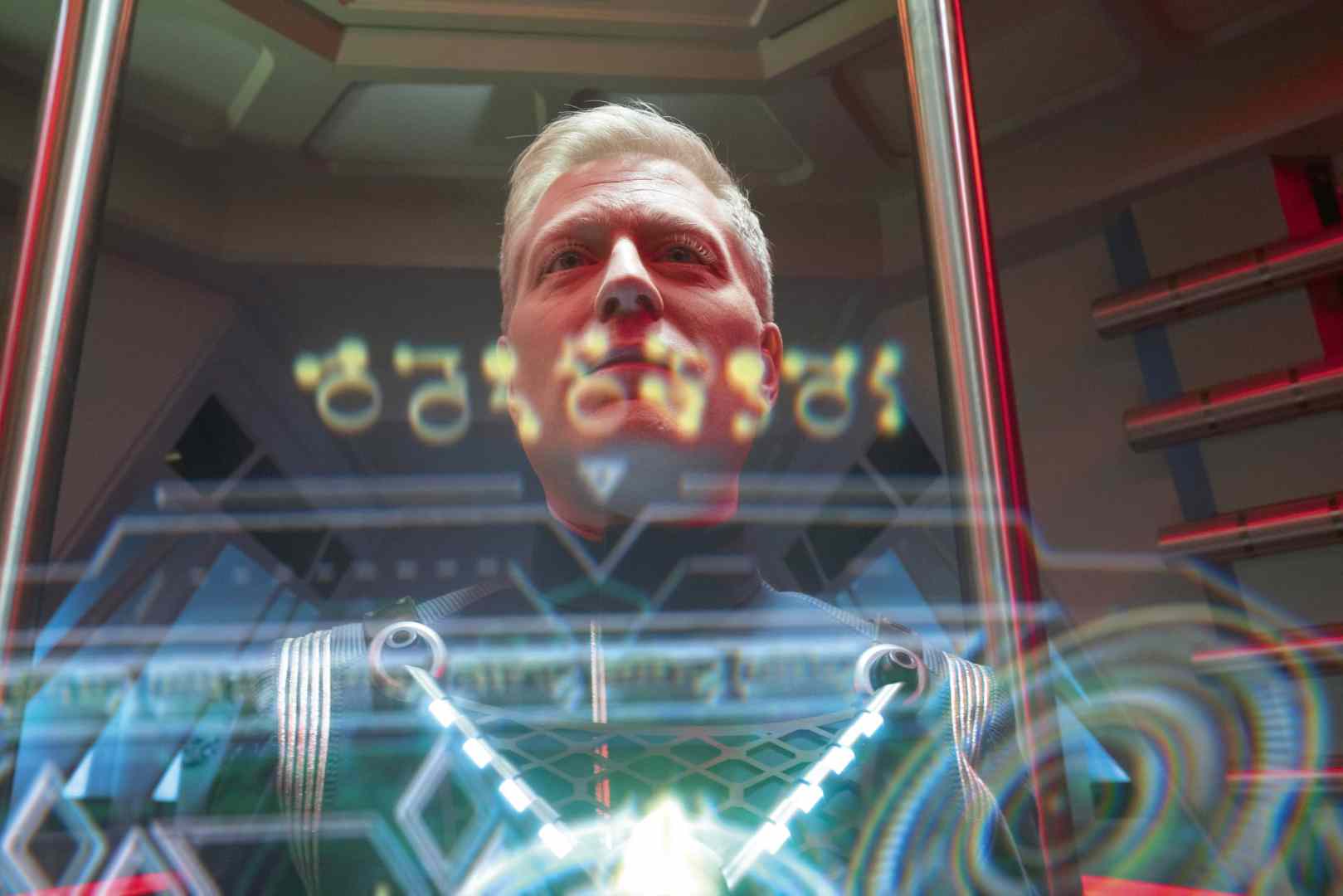

As a rule, VAD follows the specifications of the art department and harmonises the worlds on the basis of prop and set scans as well as material samples. It does not matter which world or time you are in. Virtual production sets already include interiors, expansive landscapes, abstract worlds and even photo-real cities. Compared to traditional filming, virtual production in the form of ICVFX makes it possible to realise previously unseen visions. One example of this is the Comet Alien Chamber, which can be seen in Strange New Worlds, Episode 102.

Originally described in the script as a translucent glacial cave in which the protagonists find an alien egg-shaped construct that reacts to Spock’s voice. We found the visual and interactive concept exciting and this inspired us to take the idea to the next level. To this end, we pitched the idea of transferring the hieroglyphics on the “egg” to the ice wall and linking them to the practical set with the help of an internally developed integration.

The director and scriptwriters were so intrigued by the idea that they reworked the associated act and enabled the characters to interact with the surrounding world. The light board operator was able to control in real time the elements and animations we had programmed on the virtual glacier wall together with the real light rig of the alien “egg”, transforming the scene into an interactive choreography. If that sounds like “we’ll just have a go”, it’s not. To date, not a single VAD environment has been discarded. This is mainly due to our extensive planning and the close interaction between VAD and the Art Department. The worlds are adapted in tandem with script development as early as the concept and prototype phase, so that assets have to be corrected at an early stage but not discarded.

Generally speaking, I would say that ideally the worlds should be modular in order to achieve the highest possible asset reutilisation and to use them at several locations, so-called hotspots, at variable times of day, lighting moods or weather conditions. Bear this in mind, especially when it comes to asset management – you never know when you might need a warp core!

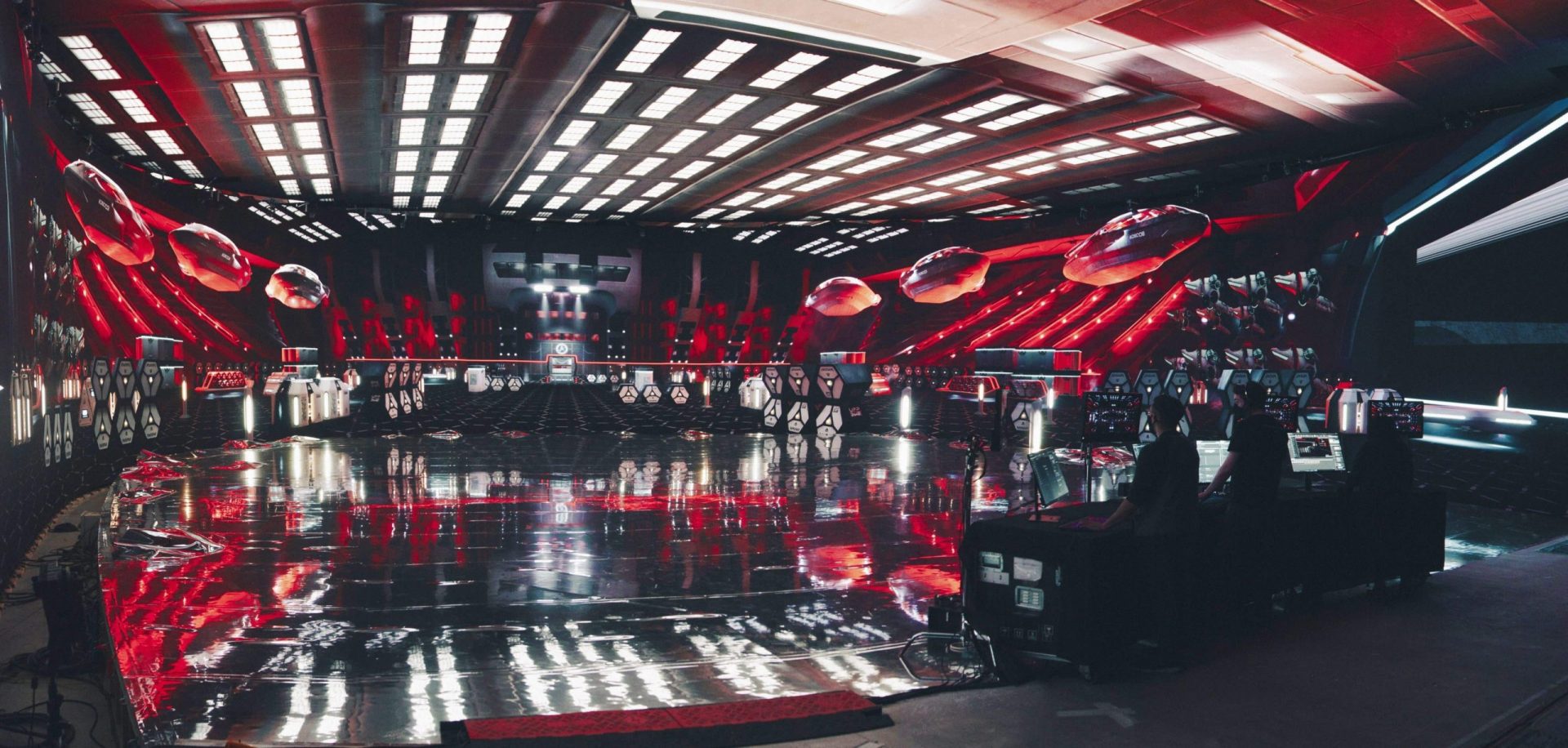

The trend is for LED stages to be designed either modularly for targeted applications or, if required, as a large volume so that you can realise a complete journey within a world. Currently, this is only possible with predefined and customised hotspots. Of course, we also want complex animations and digi-doubles to fill the worlds with life. With Unreal 5.1, the next generation of LEDs and our internal developments, we are getting closer bit by bit!

DP: What are the challenges and tasks that determine your day-to-day work?

Paolo Tamburrino: Producing a show that consists of virtual production and visual effects takes the responsibilities and workload to a whole new level. With all the new challenges, it’s more like the job of a traditional film producer. With VP, you sit down with all of the studio’s stakeholders and filmmakers from the very beginning and take an advisory and sometimes leading position in the production process.

This also means that project planning goes far beyond the dispatch and delivery of VFX shots. In addition to pre-production, which consists of many meetings with all departments, the planning of reviews, approvals, R&D, maintenance work on the LED volumes, technical upgrades through to filming include almost everything.

But it doesn’t stop there: Budgets also have to be projected and adjusted. In addition, alternative solutions have to be found and tested, e.g. miniature builds, element shoots, aerial photogrammetry (to reduce costs or catch up on missed milestones). The production of virtual worlds for ICVFX is a complex process and depends on various departments outside the VFX house. Collaboration with the art department is crucial here. Why am I picking on the preparation so much? Quite simply: Shooting shifts are very difficult to realise. it’s almost impossible to “quickly” change something in the engine, which is why preparation is everything.

Last but not least, customer education is also very important. Anyone who comes from the VFX sector knows how long it took to establish the technical language and working methods – which are still not necessarily accepted on set today. Now it’s time to expand and redefine these once again and to train previously “untouched” departments. A long process that, when successfully executed and adapted, leads to sensational collaboration and results.

To create a project like Discovery and Strange New Worlds with dozens of individual worlds requires – to put it simply – a pioneering spirit, creativity, technical expertise and “fearless” production. Communication, training and constantly expanding responsibilities are the order of the day. But it never gets boring! And where else can you say in the morning “I’m in the engine room of the Enterprise all day today!”

DP: If we go in the other direction: What kind of shots and designs aren’t working yet? Is there anything where you prefer the green screen?

Paolo Tamburrino: As with VFXs, virtual production should be used when there is a problem to solve. There are many variants: content-related, logistical, financial and much more. Ideally, ICVFX help the actors in their performance and the overall production quality to shine. There are also organisational and sustainability aspects. But if we want to make a rule of thumb: Around 6 script pages has been established as an average guideline, otherwise a virtual FullCG set can significantly exceed the cost compared to a traditional landscape created in VFX.

Scenarios that currently don’t really work from a technical point of view include underwater, complex animations, too much SFX (e.g. fog) and scenarios where the lighting has to change between scenes in the same take. White worlds or those that contain physically correct glass are also still very difficult to impossible – and floors with a high level of reflection pose an even greater challenge. On the “purely technical” side, there are sets that are too complex and make it difficult to track the camera data. Last but not least, effects that are dynamically transferred to the virtual world and have to be pixel-accurate. There are currently still small delays – for example, if you want to track a shot within the real world in the virtual world.

There are already a few workarounds and with the next generation of software and hardware, various challenges will be completely eliminated. But as I just said. Virtual production solves a specific problem – and it doesn’t always have to be an LED volume. We at PXO have specialised in this area and always find individual solutions for the respective application and scope.

DP: And what are the areas where it is (still) easier to use FullCG and compositing?

Paolo Tamburrino: I suspect that, in the foreseeable future, establishing shots such as flyovers through the worlds will be realised entirely in CG. Whether with traditional or real-time renderers remains to be seen. There are also animations that cannot yet be used due to a lack of performance. However, I suspect that these will primarily be used for orientation and interaction and will be replaced later in post.

Irrespective of the advanced technical performance in the future, animations on the LED wall always bring the risk of connection errors in the edit or the limited use of takes. In addition, there are worlds that require accurate and photorealistic real-time renderings. Currently, this problem is indirectly circumvented by producing the worlds in high-resolution in classic VFX style and later projecting them back in the LED volume – similar to a 2.5D compositing workflow.

DP: When the shoot starts, what information and preparation is needed in the team to make it work?

Paolo Tamburrino: Normally, the shoot is the most relaxed phase for our team – I never thought I’d say that. After an extensive “discovery phase” and reviews, we meet with the art department and, if available, with the DoP for the proof of concept, one of the first and most important milestones on the stage. Here, in my opinion, it is essential to analyse and evaluate the prototype of the world in terms of dimensions, layout and (optionally) with the first lightblocking. After this big, important date, there will be further interim approvals over several months, and then it’s on to the excessive testing.

Why is this so important? Because the virtual world in an LED volume is perceived much differently compared to VR and Zoom meetings, and is hardly “imaginable” no matter how good the concept art is (and we have excellent artists at PXO!) Even more important is that directors and DoPs who are inexperienced in virtual production in particular are integrated and familiarised with the technology at an early stage. Directors can only deal with things they can visualise. However, as a VP provider, these steps must be seen as interim approvals that do not reflect the actual image. For this purpose, we simulate flights within the worlds (using virtual cameras in the Unreal Engine) as well as various renderings that are used differently by the different film departments. Depending on the project, there are enormous differences here, and the decisive acceptance and merging of the worlds only takes place during the “Prelight” or “Blend Day”, when all elements and technologies are brought together.

Another serious tip: make sure that a camera configuration for the shoot is already available at the start of production – this helps to prevent surprises. And, if everything works out: look forward to the highlight when the actors see the set or their individual worlds for the first time. Always a pleasure!

DP: And after “Strange New Worlds”: What’s the next project?

Paolo Tamburrino: Star Trek: Strange New Worlds and Discovery will definitely not be our last virtual production in which we offer top-class ICVFX. In Vancouver and Toronto, my colleagues have filmed Netflix’s Avatar: The Last Airbender and various commercials. In addition to classic sci-fi, there are other high-calibre projects in development and it will definitely remain exciting; I can already reveal that much. But unfortunately not much more. If you only knew!

My role has since expanded to help PXO develop VP and VAD’s terminology and production structure, expand the production team, standardise our global locations and strengthen partnerships in the technology sector and with film studios, in addition to managing projects as EP.

Most of the core team remains in place and we are continually adding more positions and great talent. If you want to find out what we’re doing next and get involved: pixomondo.com/careers. We are looking at almost all locations. And if you’re new to ICVFX and Unreal but have expertise in animation, games or VFX, take a look at the Virtual Production Academy – virtualproductionacademy.com – vacancies and training courses are available both on-site and remotely, depending on the location.

And finally, the most important thing for successful virtual production: excellent employees! Nothing works without the great team, and certainly nothing that looks good! Thank you guys for the great reception into the team and for accompanying me through all the ups and downs.