Non-linear video editing with computers (NLE for short) has given us enormous freedom. Not only the fiddling with adhesive presses and cotton gloves, synchronised tape machines or even toxic carbon tetrachloride in magnetic magnifiers from the early days of videotape are a thing of the past. today, “cuts” are non-destructive and can be altered at will (sometimes all too often). But the whole thing has one disadvantage: the individual components are actually scattered around on storage media and are only accessed at lightning speed. If the end product is to be passed on or archived, a final rendering must therefore be carried out. Depending on the complexity of the visual processing and the codec used, this can sometimes take longer.

However, customers sometimes (or usually) have last-minute change requests. We ourselves are not perfect and sometimes only discover errors shortly before delivery. Careful quality control under human eyes is essential in any case because of technical errors. These can range from faulty field sequences to the erratic rendering errors of overheated graphics cards (just think of the infamous D700 in the MacPro). Such errors are particularly time-consuming because they can occur in completely different places when rendering again. In the final check, the entire file must therefore be reviewed one-to-one, even if only a short section has been corrected – sometimes it’s just a single line in the credits.

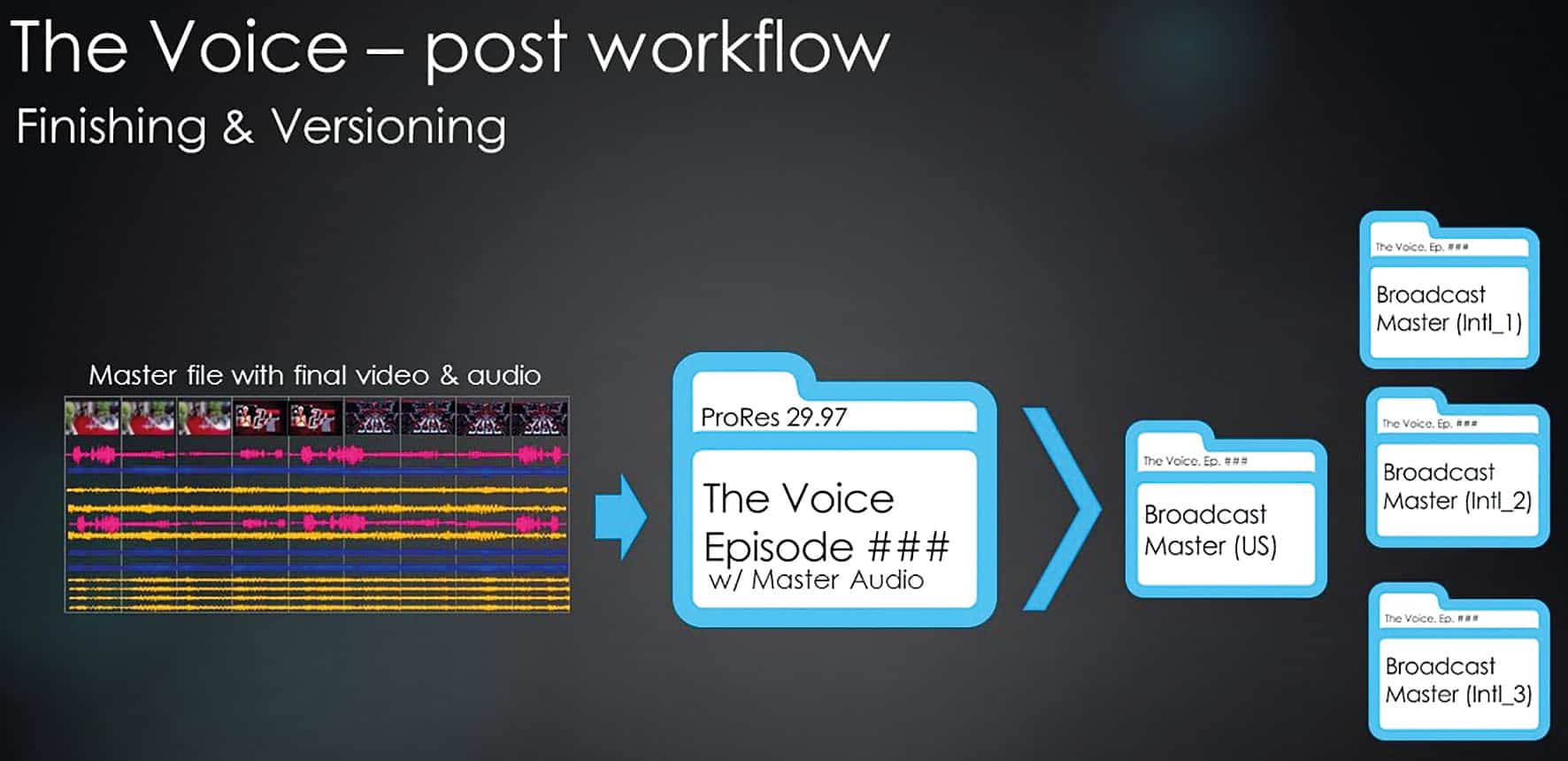

Experienced specialists in the fields of 3D animation and VFX, where the final rendering can take an extremely long time and errors often occur in completely unexpected places, therefore generally use numbered image sequences instead of contiguous individual files. This allows faulty parts to be specifically recalculated and inserted. However, such sequences take up an enormous amount of space and require very fast storage media for smooth playback. Errors during copying would also easily lead to shifts in image and sound or separate alpha masks. Compared to DPX master files (Digital Picture Exchange), ProRes 444 or DNxHR can be up to a factor of 10 smaller. In the broadcast sector, individual files in high-quality codecs are therefore in demand today, which usually also include numerous audio tracks and subtitles due to the international evaluation. What if it were possible to correct a section or individual tracks without affecting the rest of the content?

Until now, people have said: “That’s not possible!” Charles D’Autremont from Cinedeck proudly explains (presumably with a twinkle in his eye): “But we didn’t know that, so we did it.” The company does indeed have a unique selling point with CineXtools, even though Avid has announced a similar function for its NLE. However, this is still in beta testing and will only work with the company’s own system in the OP1a container anyway, while CineXtools support the common intermediate and broadcast codecs in both popular containers. In addition, they have already proven themselves at several large production houses, which is the most important thing for such a tool. The whole thing is open-heart surgery, so to speak, because the target file is irretrievably changed in the process. If you cannot rely on the integrity of all other parts afterwards, the enormous time advantage of a targeted quality control of the corrected parts alone is lost.

Technical requirements

The central condition for such an operation is that the file structure allows the exchange of any image sequences, even with changing content. This not only rules out temporal compression methods, but also codecs with pure I-frames but variable bit rate (VBR) are unsuitable. After all, you cannot rely on the content of an image to be exchanged being compressible to the same extent as the original image. What is needed is a framework for the individual images that corresponds to the maximum expected image content. Only codecs with a constant bit rate (CBR) fulfil this requirement. Apple’s ProRes, Avid’s DNxHD/HR and, as optional upgrades, Sony’s AVC-Intra and XDCAM-HD are currently supported. For XDCAM, only the versions with CBR are permitted. In addition to MOV (Quicktime), both versions of MXF are also suitable as containers, depending on the codec. While DNxHD/HR theoretically also allows VBR, in practice it always occurs in CBR, ProRes is usually output as VBR.

DaVinci Resolve also supports ProRes in CBR as an option for output under MacOS, as do the video products from Autodesk. Plug-ins from Cinedeck are available for Adobe and Avid, which enable output in CBR. Alternatively, CineXtools also offer re-wrapping from ProRes to CBR. In this process, only the container is filled with empty data so that the maximum permitted data rate can be accommodated – this is also known as padding. This is not a transcoding of the image material, which remains completely untouched (even if the generation losses with ProRes would be very low anyway). Due to Apple’s licensing policy, however, some ProRes functions are only available for MacOS, while the other parts of the program are available for PC and Mac and a CineXtools licence can even be transferred between the two systems. The programme’s system requirements are modest: OS X 10.9 (Mavericks) is sufficient on the Mac, while we tested on High Sierra. On the PC, everything from Windows 7 (64 bit) with Service Pack 1 or newer is possible. The programme is also frugal when it comes to hardware, even if transcoding and copying processes are of course significantly faster on powerful machines. During re-wrapping, the metadata in the header is also cleaned up in such a way that it should pass a quality check for broadcast – unfortunately, this is not a given with every NLE system.

If CineXtools is primarily used for quick last-minute changes, it makes sense to output all master files in CBR, even if they take up a little more space. In the test, the CBR version of a professionally produced short film with low-noise image quality and typically easily compressible elements (such as opening and closing credits) was around a third larger than in VBR due to the padding. On the other hand, the new tools save the space that new full-length render files would take up during corrections. If ProRes is frequently delivered in VBR, the re-wrapping by the CineXtools is primarily dependent on the disc throughput. When reading and writing the material to a single USB 3 hard drive, you have to expect considerable waiting times, whereas padding is done very quickly with two separate SSDs or fast RAIDs. Our test film took almost seven minutes on such a single hard drive, while the process on an SSD RAID connected via USB-C took 45 seconds. A free tool for re-wrapping with automation via watch folder has also recently become available. For projects where the length and format have already been determined but most of the content still needs to be created, CineXtools can prepare a suitable blank file with all the desired additional tracks using “Create Insert Media”.

The above conditions apply to the full-length master file. The patches to be inserted (i.e. the corrected sections) may also be in VBR and even in another of the above codecs and containers, as they may be quickly converted during insert (this is then logically a real transcoding). JPEG2000 in YUV with 4:2:2 subsampling is also accepted as a .mov file for patches

for patches. Even the support of several formats for single image sequences such as .dpx, .tiff and OpenEXR is in the works: we have already been able to try it out with .dpx in 10 bit and .tiff in 16 bit. Even different colour depths or colour spaces are accepted for patches, but this can certainly lead to image jumps when inserting into parts of existing scenes. The responsibility for this therefore lies entirely with the user, who should select the same output format and the same software as the original file if possible. Logically, insertions in the appropriate format without recoding are the fastest. Changes to audio or subtitle tracks are possible without affecting the picture, even with files in VBR. The resolution can be over 16,000 pixels, but must be the same for the patch and target file, as must the frame rate and line structure (interlaced or progressive). Sound to be inserted from external files must be in .wav format with 24 bit and 48 kHz, .aac or even .mp3 are not accepted.

The tools

First and foremost is “Insert Edit”, i.e. the insertion of patches into a film file. The term is not used here in quite the same sense as in conventional NLEs, as the area is not inserted in the target file, but overwritten in the same length. This is more of an “overwrite” in the modern sense, but it was no different with tape machines. Because of the similarity to working with tape, the manufacturer also likes to use analogue terms such as the classic “Black Striped” for an empty file – many users are obviously still familiar with this. Video, audio and captions can be selected in any combination as content to be changed, the timecode (TC for short) can be rewritten for patch and target (“Restripe”) and the reel tape ID of the target file can be corrected.

For audio, there are also extensive options for reassigning up to 32 channels in patch panel style, adding external sound files and, if necessary, crossfades for critical connections of the sound content. The target file can be renamed, but editing is still a change that cannot be undone. If you have enough time for copying, it is therefore better to work with duplicates.

The actual insert cut is very simple: For example, you specify an entry point in both windows and an exit point in one of them, and the area to be replaced is marked in both windows (known as a 3-point cut). The convention of band cuts applies here, i.e. the out point corresponds to the first image that is not changed. If the TC matches, the cut points can also be conveniently copied to the other window. Finally, there is an opportunity for a preview or to trigger the hot cut, which does not take place without a warning that the file will inevitably be changed. Incidentally, unlike a rendering process, the file can already be checked in a player while a somewhat longer insert is running elsewhere. This means that another person can continue quality control under time pressure while corrections are still being made.

A further tab (Multiple-Source Single Target) allows a whole list of patches to be inserted into a target file, so basically not just batch processing, but almost a rudimentary editing function. The target file can of course also be a “Black Tape” generated in the programme with “Create Insert Media”. With “Extract Audio to File”, you can extract audio tracks from existing films and write them to separate files; you can also select a different track assignment. The “Rewrap & Audio Versioning” tab is also basically self-explanatory: In addition to the conversion from VBR to CBR, comprehensive reassignment and the addition of audio tracks are offered, whereby their starting point can be redefined in relation to the TC of the target file. If required by the customer, this tool can also convert a CBR file back to VBR after correction. Pure audio inserts are also possible with VBR or GOP codecs anyway.

Finally, the programme also offers the option of editing or adding subtitles: Corrections are written directly into the file here. Subtitles as .mcc and .scc files are supported directly, as is extraction to sidecar files. Subtitles (or closed captions) can be imported in .cap format (Cheetah International) or as .scc files (Sonic), unfortunately not in the popular .srt format. But there are plenty of tools for converting subtitles: free online services such as subtitleconverter.net, subconverter.rest7.com or rev.com/caption. Those who are reluctant to entrust their texts to a third-party website will find professional tools in Subbit’s Subtitler (PC and Mac) or Annotation Edit Suite (Mac). Another option is the editing of metadata in accordance with the British broadcast standard AS-11 DPP (Digital Production Partnership), which is increasingly gaining acceptance in North America and Scandinavia.

Getting to know

While the available Quick Start PDF still looks a little immature and some links are missing, the manufacturer provides easy-to-understand and detailed video tutorials(cinextools.com/video-tutorials). They all look like Mac, but apart from ProRes conversions, everything works exactly the same on a PC. There is also a freely available basic version, which is limited to formats up to 10-bit colour depth, maximum 2K resolution and master files with two audio tracks. If you would like to get to know the full version better, you can request a one-week trial licence. Incidentally, the licence is issued using the iLok system familiar from Avid. This is somewhat cumbersome, but does not require a constant Internet connection, as is often required for production machines. The licence can be transferred to a computer via a temporary online connection or written to a dongle for full mobility.

The user interface still lacks clarity, with hardly any visual differentiation between important and less important buttons and information. Our test version also showed some minor quirks when controlling the Playhead in some formats. However, these are blemishes, activated tooltips make the individual functions quickly understandable and the core functions ran smoothly with clean source files. Unfortunately, it should be noted that some software and hardware manufacturers only loosely adhere to the standards, and FGPA-based cameras and field recorders in particular are notorious for this. It is therefore essential to use the test version to check whether your own workflow works without any problems. In our test, for example, the mixed insert between XDCAM-HD material and DNxHR in the MXF wrapper from DaVinci Resolve did not work reliably, while there were no problems in combination with DNxHD/HR in the MOV wrapper. However, Cinedeck is known for dealing with such problems quickly – this was also the case in our test.

Comment

At a time when editing programmes – albeit sometimes of dubious reliability – are being given away, the price of CineXtools seems rather steep. However, this programme is not aimed at amateurs and semi-professional users, but at users who will quickly amortise the price through massive time savings. This ranges from quality control for last-minute corrections to the creation of different versions from partially identical material, right through to internationalisation and multiple evaluation with subtitles or varying audio tracks. In addition to Technicolor PostWorks and NBC Universal’s “The Voice”, even pure audio houses such as RH Factor are already using the software. Anyone in DACH who is interested in CineXtools can order it from DVEAS (www.dveas.com).