No hair, no fur, no skin; robots actually guarantee the artists a quiet job. The production of Transformers was different: the highly complex extraterrestrial robots consist of countless individual parts. Added to this were difficult simulations for collapsing buildings. The team at ILM had to look for new approaches and came up with a number of solutions that made a decisive difference to the company and the industry.

Could there be a better subject for a summer blockbuster than watching gigantic robots from a distant galaxy smash themselves to pieces in the centre of Los Angeles? And can you think of a director better suited to staging such carnage than Michael Bay, who has already directed “Armageddon”, “The Rock”, “Pearl Harbor”, “Bad Boys” and “Bad Boys II”?

The names of the executive producer and the visual effects studio also stand for decades of experience with action films: Steven Spielberg and Industrial Light & Magic. George Lucas’ company took on the task of creating the massive bots and the enormous destruction.

Taken together, the mixture of Transformers, Paramount Pictures and Dreamworks SKG is this summer’s potential blockbuster.

From toy to film

Starting with the Hasbro toys that were launched on the American market in 1984, a small universe was created: in the 1980s, the Marvel publishing house first published a comic story, which was later developed into a television series and an animated film.

Transformers tells the story of the clash between two alien races, the Autobots and the Decepticons, who come from the planet Cybertron. Both are searching the Earth for a magical cube called the Allspark, which was once discovered by an ancestor of film star Sam Witwicky (Shia LaBeouf). Unbeknown to Sam, he possesses the map that shows the way to the hiding place of the Allspark. On Earth, the heroic and good Autobots disguise themselves by transforming into cars and lorries, while the evil Decepticons transform into military vehicles. The leader of the Autobots, Optimus Prime, is a lorry tractor, Megatron, leader of the Decepticons, is a Cybertronian jet.

New tools

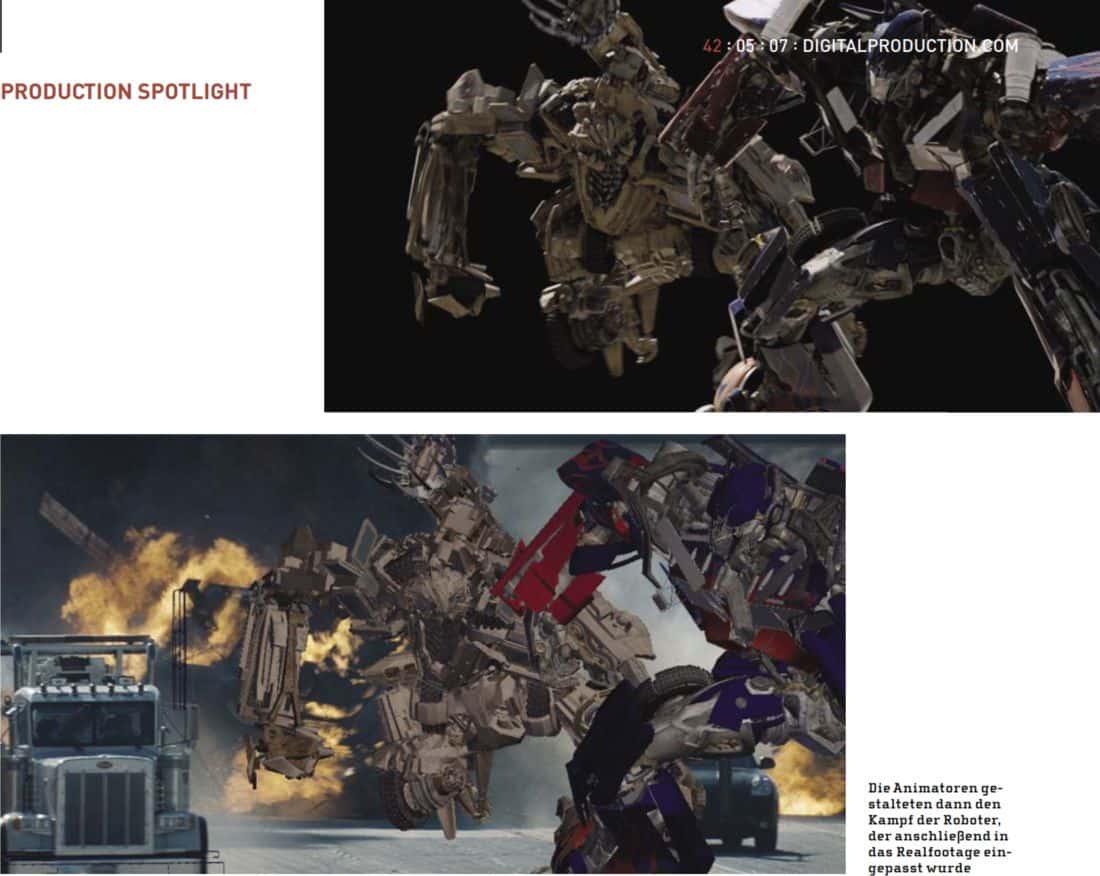

To create the visual effects for this film, ILM had to develop new tools and techniques under the guidance of its Oscar-winning visual effects supervisor Scott Farrar. Selective ray tracing helped to reduce render times. A new type of rigging system and a controllable rigid body simulator helped the animators manipulate robots made up of thousands of individual parts. For the task of destroying buildings and concrete, ILM used both proprietary and off-the-shelf software.

“We call this a ‘hard body’ film, as opposed to productions with actors who have hair, fur and skin. So you’d think that shouldn’t be that hard,” says VFX supervisor Scott Farrar. “But we’ve never had to reach that level either. I worked on Minority Report, which was about concrete and cars, but we couldn’t work it out to the level we can now. We had to programme a huge amount of software for that film and solve countless individual problems so that the effects would actually look better in the end.”

Original vehicles and concept art

It starts with the robots themselves. Every single robot – except the Decepticon Scorponok – transforms into or out of a vehicle in the film, often in full motion. ILM had a fleet of real vehicles as reference material, including cars supplied by General Motors and military vehicles provided by the US armed forces – sometimes these were entire vehicles, but sometimes only photographs and videos were available.

For the robots, the artists had concept art as a reference. But when ILM received the concept art designs approved by the director for the film, it quickly became apparent that the concept artists had not bothered to build the robots from the parts of their camouflage vehicles.

“On some of the early robots, we were trying out how we could move a door into the chest piece and scale it,” recalls associate visual effects supervisor Russel Earl. “After a few weeks, we decided to take our chances, match the artwork and hope we could find a way to get them to transform.”

Therefore, unlike originally planned, the robots now also contain parts that do not actually belong to their camouflage vehicles. In some cases, this involves several thousand individual parts. “To achieve the mass that the actual shape of the robots requires, you have to use more than a car has in individual parts,” explains Earl.

Surfaces as if painted

A team of modellers led by Dave Fogler built the robots and CG vehicles using Subdivision Surfaces in Autodesk’s Maya. Viewpaint supervisor Ron Woodall led the texture painting team, whose job it was to add scratches, dirt and even cracks and tyre marks.

“A lot of stuff that you think is modelling is actually painted,” reveals Fogler. “We wanted to keep the models as light and economical as possible, but the debate isn’t settled on which is more complex to render: geometry or displacement. It could be a draw.”

Woodall adds: “For interactivity, displacement is the best method. But rendering geometry is cheaper.” The painters worked in Photoshop and ILM’s in-house software Zeno. The team quickly realised that the robots had to look dirty to be believable: shaders couldn’t do it. “Without the wonderful work of Ron Woodall, the technical directors would have been at a loss,” praises Hilmar Koch, who supervised the work of the TDs. “Synthetic shading would look boring without the painted effects.”

Selective ray tracing

The shaders had a different task. “I think one of our biggest achievements in terms of shading is that we can switch ray tracing on and off as required,” Koch reports. “With selective ray tracing, we can soften certain parts of a setting.”

In order for the robots to successfully and credibly fit into the respective environments and to make the interaction with the live actors more convincing, the targeted use of reflections was crucial.

“It’s difficult enough to light a car in CG so that it looks real. But we took the car, dismantled it into a few thousand individual parts and put it back together again in the shape of a robot,” Earl explains. “For example, if you take a part of the body and break it down into a bunch of individual parts, you’ve obviously lost the shape of the car, but we still had to give the audience the feeling that when they look at a particular part of a Transformer, they’re sure they know what part of the car it is. A lot of that effect is based on reflections.”

To reflect the real shot scene, the technical directors used 8K quality environment maps. They stitched these together from photographs that they had previously taken on location. Ray tracing was added as required for certain parts of the robots. ILM used Mental Ray for ray tracing on the one hand and RenderMan for scanline rendering and ray tracing on the other.

“We control this via the shaders and the user interface,” says Koch. “You can select an individual part of the robot, then click a button and the ray tracing starts.”

Part by part

Modellers built the robots from thousands of components. The smallest robot, the Decepticon Soundbyte, which disguises itself as a radio instead of a vehicle, has 871 parts. Optimus Prime, on the other hand, the leader of the Autobots, has 10,108 parts. To give the animators control over all these elements, the character developers developed a dynamic rigging system that allowed the animators to arbitrarily group and regroup geometry in different ways.

“What’s really unique is that the animators can move every single piece of geometry you see when a robot appears on screen,” praises Digital Production Supervisor Jeff White. “There’s a basic rig with animation controls that the animators use to move the robot around the scene. If they use a second level of refinement, they can group any combination of parts together and make them move completely differently. They put the pivot points exactly where they want them.”

Facial animation

This became particularly important for facial animation to repair intersections and interpenetrations of hard metal parts and create transformations. Many of the robots, especially the Autobots, have speaking roles. To create facial expressions, the modellers built a turbine system for the eyes with 50 metal arms that dilate and constrict like a pupil; for the lips, they used split metal pieces and fixed cones in the mouth to simulate the tongue and teeth.

Robots with body language

“Within a scene, we started our work with posture and body language. The next step was to try to convey a certain movement or feeling with the overall pose,” explains Shawn Kelly, who was one of five animation leads involved in the production. “Some robots are a little more athletic than others, but they’re all out there because they’re hardened fighting machines. They all have a similar fighting style. The facial expressions end up being the icing on the cake: The way their eyes move and where we place a wink.”

For the robots’ fighting style, the animators used a mix of video reference footage Michael Bay had shot of stunt actors miming Japanese and Hong Kong-style martial arts, as well as motion capture data from the stuntmen. “We used the reference as a guide, but we did a lot of the action with keyframes,” says Paul Kavanagh, one of the animation leads. “We always tried to give the impression that the robots have a weight of their own and can also move very quickly.”

Little tricks

The animators cheated with the transformations. “We used tricks,” admits Kavanagh. “We obviously tried to make the transformations look as real as possible and think of as many parts as possible, but we couldn’t always account for every detail. Once we had the most important parts working, we added the rest more or less on the fly and didn’t worry too much about it. What was a daunting prospect at first turned out to be a very enjoyable task to work on in the end.”

Generally, the animators animated the robot and its camouflage vehicle as they played their part and then handed over the poses to the creature development department for the transformations. However, as the work progressed and the animators used the dynamic rig, more and more animators also created the transformations.

Insect robots

One of the robots, the Scorponok, never transforms. Instead, its behaviour is more reminiscent of an insect than a human. Animation supervisor Scott Benza played the robot Scorponok directly, like a kind of virtual animatronic. He employed rigid body dynamics by using rotational forces, forward velocity and the like.

“We took our rigid body simulation to a whole new level for this film,” says Benza, looking back. “We now have methods that allow us to drive characters with virtual motors; we have settings that are driven by fixed simulations.” Benza baked the simulation data onto animation controls so that the animators could change them afterwards in the same way they would change motion capture data.

Massive destruction

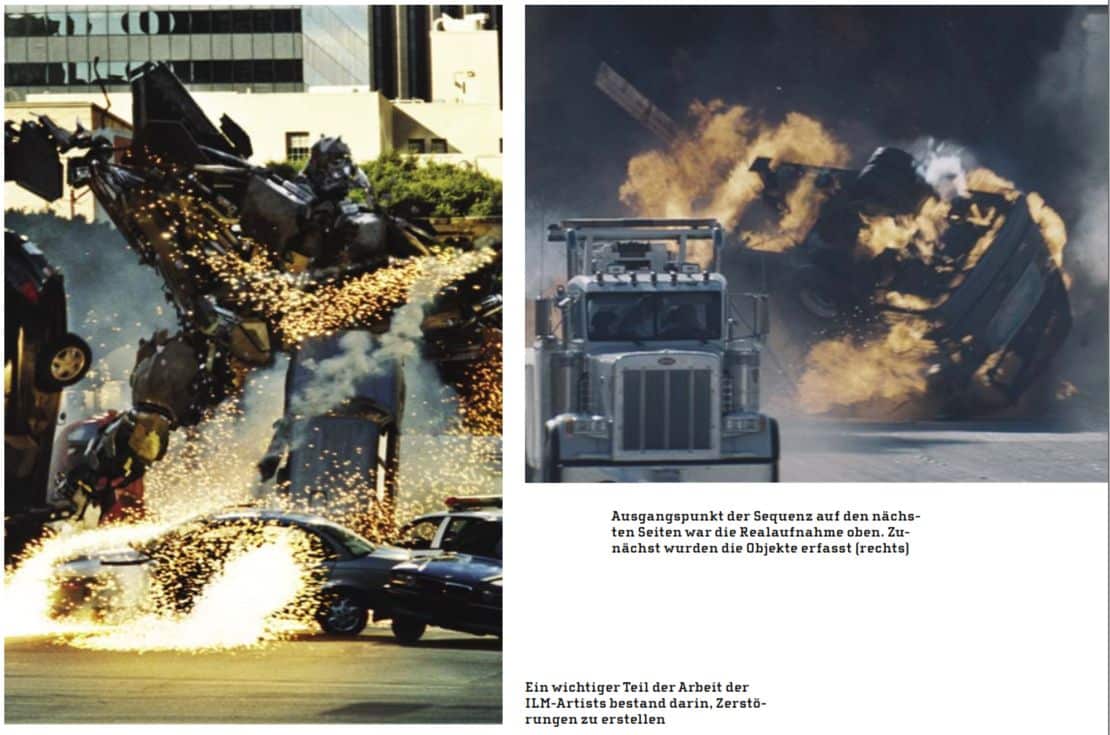

Wherever the robots fight or simply drive down the road, they cause massive destruction. Michael Bay decided to shoot much of this destruction and explosions in real life on set, but for some shots, especially towards the end of the film, it was necessary to shoot them entirely in CG.

“We had to break up concrete and destroy buildings,” explains Koch. “We had bursting walls and falling debris. And we built quite a few smoke trails, all with particles. We set fires, knocked down lampposts, street signs and traffic lights, smashed windows, ripped fire escapes off buildings and destroyed all sorts of structures. Without 64-bit rendering and 64-bit computers, we wouldn’t have stood a chance in this production.” The team used both proprietary and off-the-shelf software for the destruction.

Difficult conditions for lighting

ILM’s lighting artists had to overcome a very special challenge in this production: The smoke-filled scenes with the giant robots were particularly complicated to light. To ensure that the lighting artists could work faster, ILM’s research and development department supported the team in improving the lighting tools in the studio’s own Zeno software.

“We tried to hide as much of the underlying infrastructure as possible,” explains Senior Technical Director Hilmar Koch, “so that the rendering TD only saw what really mattered.”

While most cinema-goers will probably be concentrating on the action in Transformers, visual effects supervisor Scott Farrar is delighted with a success of a more subtle kind. In his opinion, the modelling, painting, rendering and lighting in this film represent a turning point for the visual effects industry.

“We’ve always had the iron rule that, in principle, it looks better to shoot a model in real life than to realise it using computer graphics,” he explains. “But I think we’ve finally overcome that hurdle with the achievements of the production of Transformers.” And that’s a transformation that even a Cybertron would approve of – whether Autobot or Decepticon.