Table of Contents Show

It connects via Bluetooth to a companion app for precise color measurement, exposure monitoring, and adjusting light conditions. This portable device is especially useful for filmmakers and photographers working under difficult lighting environments.

No, this is not about calibrating monitors again (see here). This time it’s about one of the hardest tasks in post: matching cameras. Sure, we all know that different manufacturer’s cameras interpret colors quite differently and all we can do about it is color grading. Even two samples of the same camera can look slightly off. But given that you set everything correctly in the menus and there are still very obvious shifts, there is another culprit to suspect: the light!

Metering color of light

Datacolor is known for their devices to calibrate monitors for years and we are soon going to test a recent one. But now they added a meter for light sources by acquiring Illuminati Instrument Corporation: renaming the Illuminati IM150 to Datacolor LightColor Meter Model LCM200 (LCM for short). It looks quite futuristic and remotely reminds of their own Spyder colorimeters. It has no displays other than a few LEDs to indicate functions, since it works only in conjunction with a free app, both for Android or iOS. We have tested it under iOS 18.4.1 with an iPhone 15 Pro.

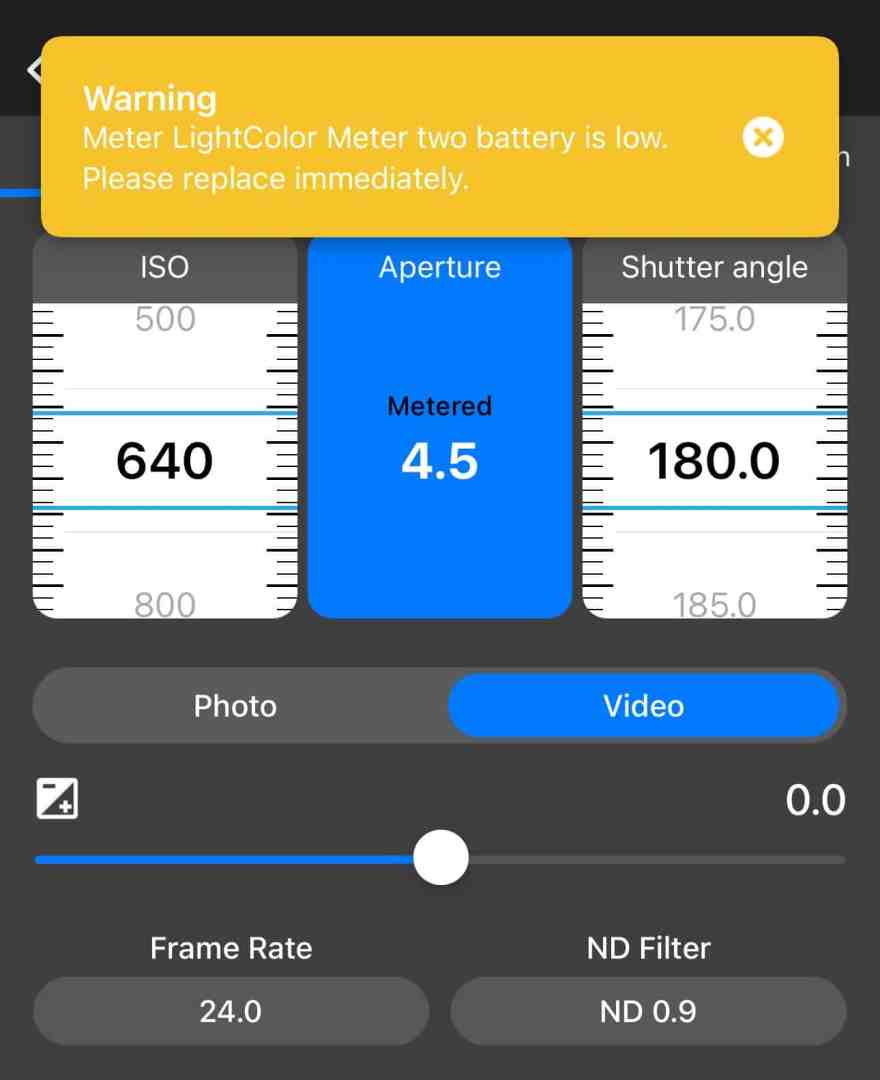

Since every professional would still know what a light meter does for exposure, we are focusing on color here. It needs mentioning though, that the LCM doubles as a pretty good exposure meter for incident light. You may need some correction against your own camera, since camera ratings in the semi-professional range are a bit off more often than not. If you don’t check for correction, you may get nasty surprises using two different cameras in your scene.

Hardware

The LCM is less than 80 mm at its widest and weighs only 73 grams with batteries. Yes, two AAA batteries. While you may complain that this is not very friendly to the environment, neither are rechargeable devices with batteries that are practically impossible to replace when worn out. I suppose you can all name a compact device that has this disadvantage. A triple A battery is found in about every supermarket these days and also dropped there for recycling in most civilised countries.

The ones in the LCM can last pretty long, since there are settings for both the time to go to sleep and the frequency of constantly monitoring the light. The latter is activated optionally, while you can trigger single measurements both on the device or in the app. If you leave it monitoring all the time and measuring every few seconds, the batteries are drained within hours. But it uses very little power in standby and the batteries last for several days of filming with more reasonable settings for ambient monitoring.

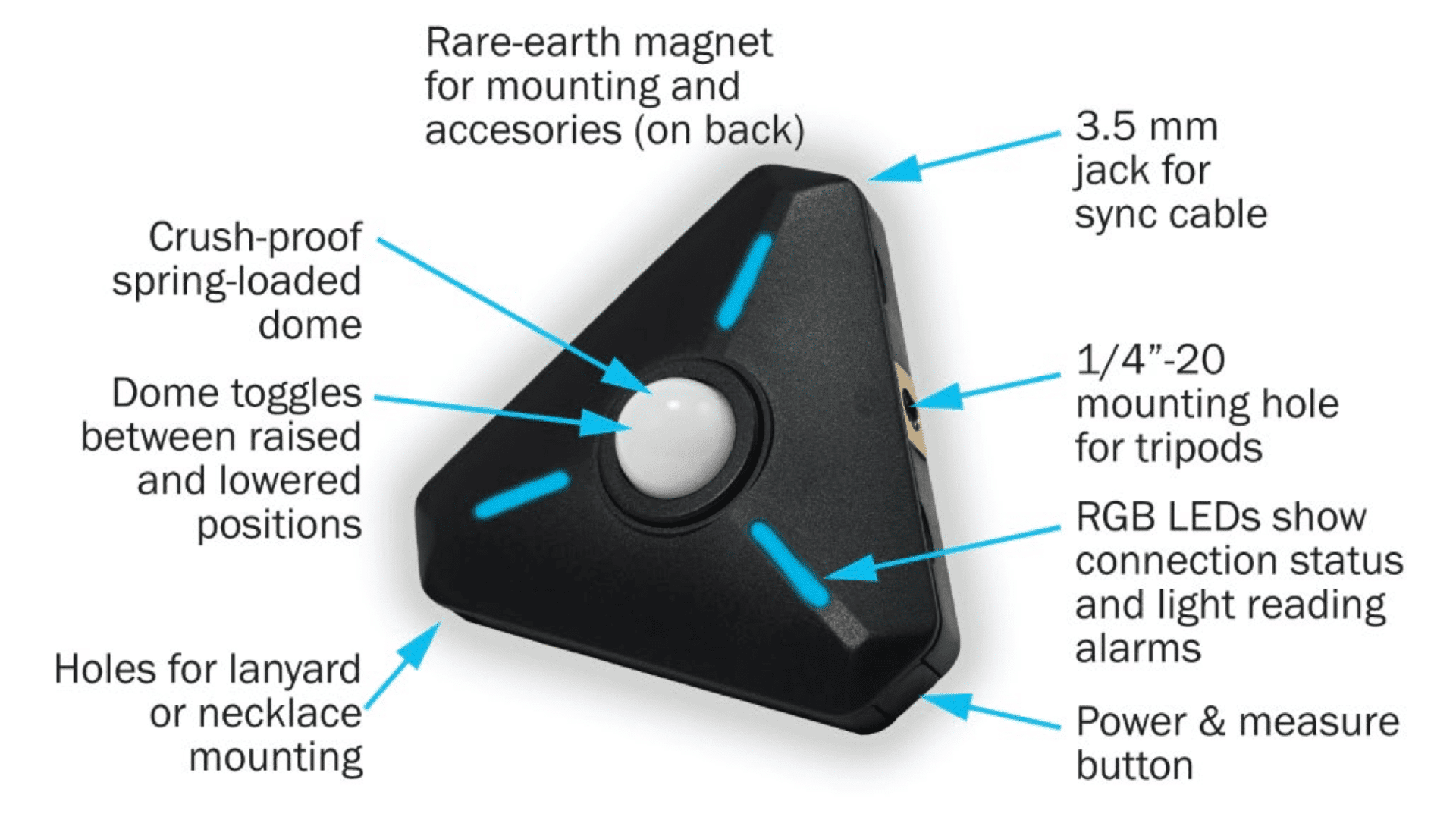

You may attach a lanyard, fix the LCM to a support with a 1/4″ screw or attach it to any surface that will react to the pretty strong magnet on the back. The battery cover is also held by magnets, so you don’t need any tools when changing them. In the pretty sturdy protective case there’s another magnetic piece to set the LCM upright or hold it safely in your hands without accidentally covering it or touching the button. A second one can clip it to clothes.

Apart from the power switch, which doubles as a trigger, there’s also a 3,5 mm socket to trigger a photographic flash if yours still offers that connection. If not, the LCM can be triggered by the light burst of the flash. Finally, the dome to measure incoming light can be exposed fully or set in a bit to narrow down the angle of light seen by the LCM. Everything else is in the app.

Software

The device is connected by Bluetooth, 4.0 to be precise, and we didn’t have problems pairing it or loosing control when in reasonable range, even with quite a few other BT devices around. While it’s very convenient to have your measuring device a few meters away from you and in awkward positions, remember that BT is a short range technology. The maximum range of 24 meters mentioned in the manual may rarely be reached, if at all. As long as it’s connected, values from the LCM are transmitted in about one second.

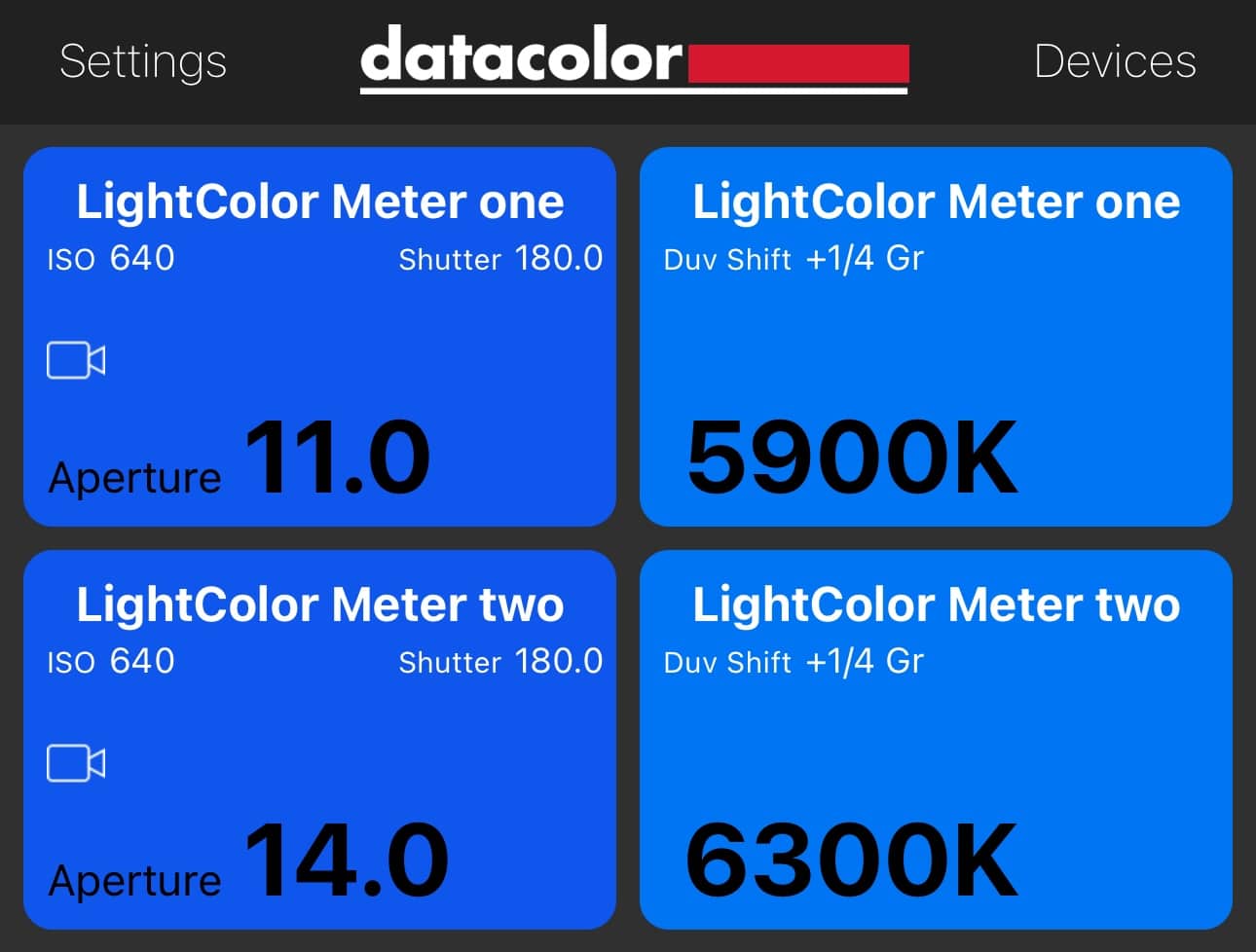

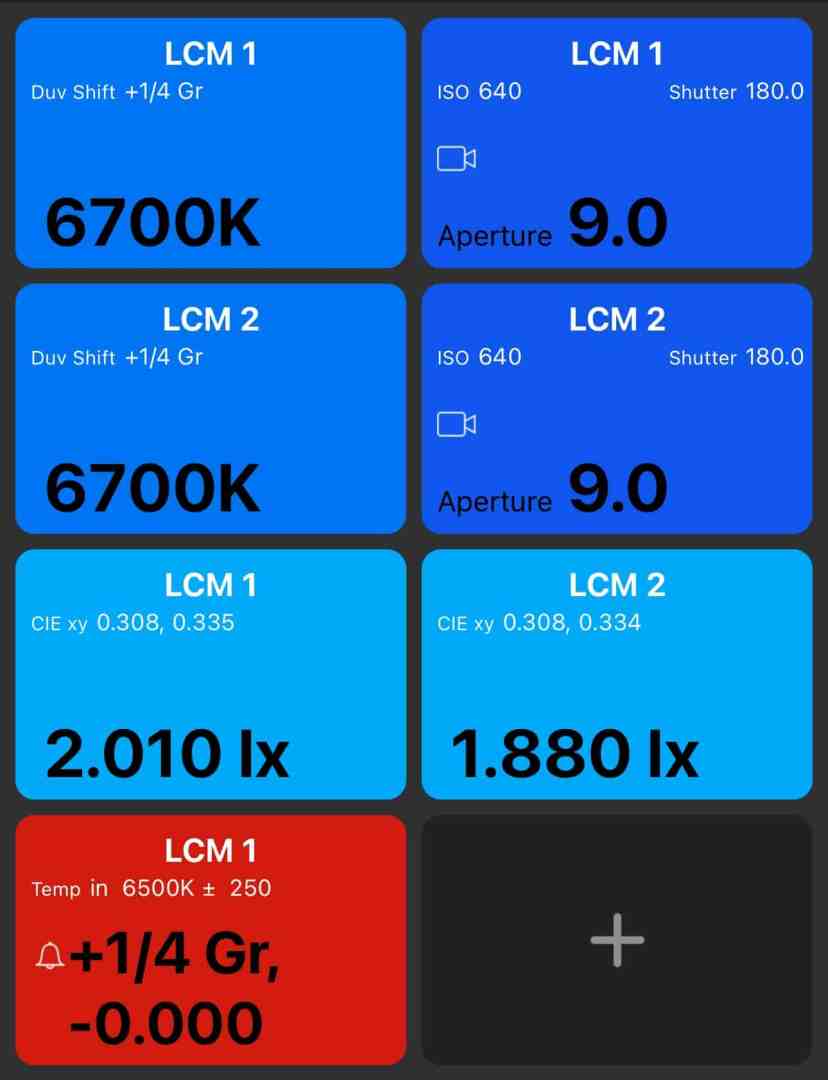

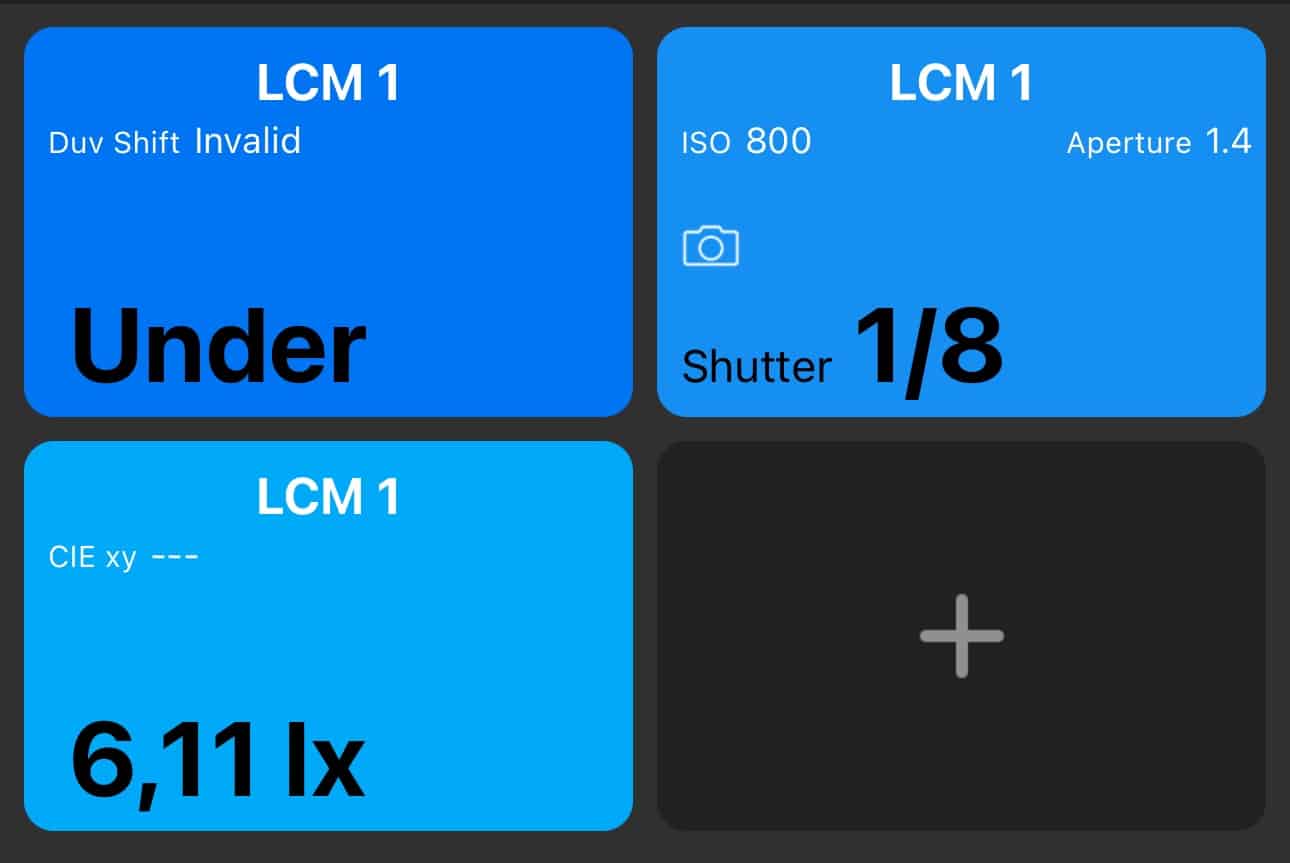

The app can control more than one LCM, and it’s highly configurable. For some functions you have to dig pretty deep into submenus, though. Once a device is paired and renamed, if you like, you can add them for different functions to a central screen.

That central screen can display exposure (both photographic or filmic), color and light intensity for every device. You can also define alarms if a certain range of values is not met any more, which will also flash the device seeing that. The colourful LEDs on the instrument can be automatically dimmed to match the environment. They deliver such a lot of information that you may frequently the consult the manual as a beginner. While the QuickStart is pretty limited, you will need the full manual (a PDF download) to explore the exhaustive functionality. It comes in a several languages.

A word to our German readers: while there is a German version of the manual, its screenshots are all in English, which may be confusing. The translations for the app itself is generally pretty good, as is the German text in the manual. There are still some confusing mistakes, like “Reichweite” for limiting values when setting an Alarm or simply uncommon expressions like “Erledigt” for “done”.

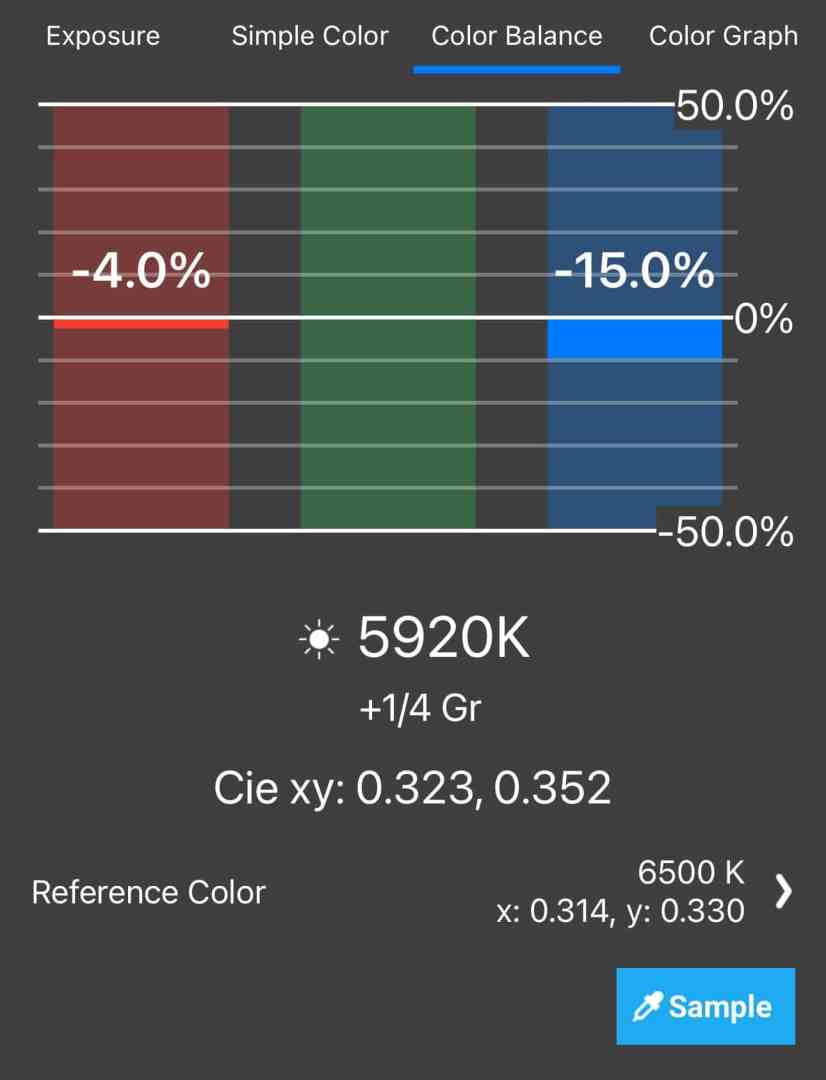

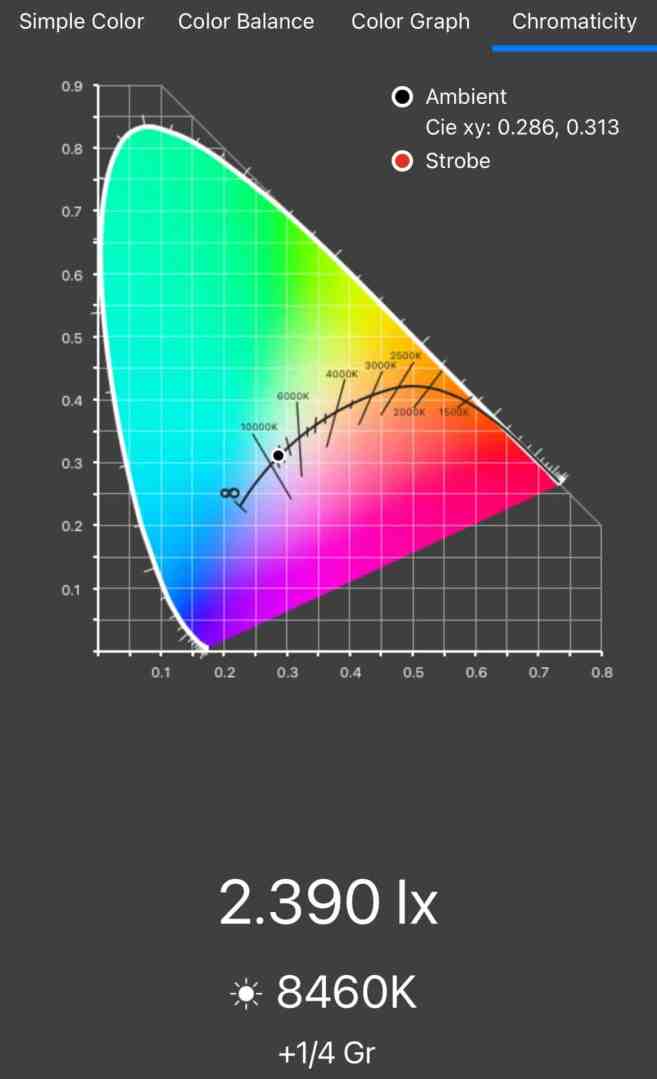

Once you tap on one of the fields in the main screen, you can go really deep: all the way into color balance with CIE values, a color graph, and chromaticity diagrams. You can also choose to calculate the effect of all kinds of filters you may have applied, from NDs into a long list of professional color correction filters, and even have more than one instrument compared here. The user interface is not always really elegant, though.

Only the Color Graph is a place where we found some minor flaws in the current software. If you have compared instruments values before, switching to a display of filters will not update right away. Either the app needs to download data here, or it needs some switching back and forth. And then, you should give very short names to your devices or they will cover other values and be truncated on the right side. Unfortunately, you can’t extend the display by going horizontal.

Application

Now, why would you need such an instrument? Well, in the old times things seemed to be easy: there were two types of analog film, for daylight and for tungsten. Even most early electronic cameras followed this simple pattern. The color of tungsten light is indeed pretty well defined. The classic ‘Redhead’ had a color temperature value around 3.200K, and most household bulbs were close. They even don’t shift much with ageing, we tried a nearly burnt-out bulb vs. a fresh one and found them very close. Tungsten lights get a lot warmer (shifting to lower values) when dimmed, though.

But is daylight really a fixed value of 6.500K? Or wasn’t it 5.600? There’s even this myth that a guy working for Kodak stepped out into the daylight from their lab at 10 a.m. and measured the value. We can’t verify this, but if you want something more scientific, have a look at this tutorial, by John Hess for Filmmaker IQ. In reality, daylight can change its value massively, caused by weather, your location (the height in particular), and foremost by the time of day. Everyone in film knows about ‘golden hour’, when the daylight can even be a tad lower than the number for tungsten. OTOH, a blue sky at noon high in the mountains can emit over 10.000K, and even in Central Europe at 230 meters AMSL in summer we see well over 8.000K at noon.

For a mixed light situation, you may not always aim for the combination of warm practicals vs cool daylight, like in contemporary fiction. You may want to get a neutral look, like in interviews or documentaries in general. With modern adjustable LED sources, this is an easy task. That is, if you know the current value of daylight coming in. With the LCM it’s easy to balance such a scene, even easier with two of them, actually.

But with the widespread use of energy saving technologies things have changed massively for artificial lighting too. Even in the old times, people would know that it’s a good idea to check items like fabric and clothes under different lighting to judge their color. But nowadays, you can’t even be sure about continuity from one light source to the next in a shop or a living room. From simple household ‘warm’ LED lamps we received all kinds of values between 2.100 (which is about the same as a normal candle) up to around 3.100K. Dimming didn’t change those values much, but even some lampshades did.

Measuring, and changing the LED fixtures if needed, is essential for continuity when editing in such an environment. Sure, you could walk around with your camera and a grey card and take the values, but the LCM is definitely more convenient. Having your values shown on your phone also spares you writing them down, just make a screenshot. Under controlled environments like a studio, the instrument will help you to know what you’re doing when setting up intentional shifts of color with filters or adjustable lights. Finally, for day exterior shooting, you can set the color temperature in your camera and tell the LCM to warn you if the light shifts beyond a defined limit.

Precision and a limitation

There are no calibration charts included with the LCM, but we had two of the for testing. They always showed the same value under identical conditions with only minor deviations of up to 30 degrees Kelvin. We tested it with a video LED light of known good quality (CRI over 95), and when that was set to 3.200 it was measured as 3290. When the light was set to 5.600K at full power we got 5670 on both instruments, when dimmed it got slightly higher at 5850 and 5820, which is common with some LED sources. Next, we compared to the values from a Cine Meter II on the iPhone and from a Sony A7IV by using a Kodak grey card. BTW, don’t try white paper or clothes: as expected, the values were between 500 and up to 1.000 higher for those. This is caused by fake whitening since coloring is added which converts invisible UV to visible blue, counteracting yellowing of such materials.

In daylight, the Cine Meter showed 6.640K and 1 1/8 green, while the LCM read 6.530 and 1/2 green. The Sony measured 6.700 and a correction to magenta of 2. Not too bad, considering that we compared incident light with reflected and that the camera may use specific corrections for Sony’s color matrix. A difference of 500K is generally considered the threshold of visibility for the human eye, but cameras may show a shift at smaller differences. Under another artificial light of 3.200 the LCM read 3.420 and 0 green, Cine Meter showed 3450 -1/8 G, and the Sony 3.400K and G2 (which equals to some compensation of magenta).

Sensitivity of color measurement is somewhat limited: Evening twilight can still read an aperture over 1 with ISO set to 3.200, but you’ll get an “under” warning for color. On rare occasions, very close to that limit, we got crazy values over 17.000K. Usually the LCM clearly indicates when light is too low to measure color. Regarding exposure, it beats most older professional meters at low light.

One problem can’t be detected by such an instrument, though: very narrow spikes of one strong color from LED lights, like the notorious reaction of Sony cameras to intense blue LED. This a technical limitation of any colorimeter, and it also means you can’t measure the CRI or TLCI of a light source. Only a spectrometer like the Sekonic C-800 SpectroMaster can reveal such issues, but that device has a minimal street price of over 1.200 €, while the price of the LCM is under 400 €.

Conclusion

So, who may need this? Let’s look at a few use cases. If you are working under tight deadlines and don’t have time and/or money for delicate color grading, you can monitor changes of light in day exteriors with the LCM. You’ll get a warning if the values deviate and adjust your camera’s white balance and exposure accordingly instead of having it running on automatic, which can be quite irritating for viewers and is hard to correct. You can measure mixed light situations for interiors and decide if you want to change the artificial lights or use gels on them. Where you can’t do that, like in industrial environments, a color chart may still be more useful.

All of these are of particular importance for fashion with delicate colors, artwork, or critical product shots like food, which are often filmed these days under difficult conditions with cheap light fixtures and without full control of the light like in a traditional studio. Finally, you can even use adjustable lights in your grading room all matched to your calibrated screen for consistency. In a time when many light sources and even cameras are controlled by apps, it’s quite convenient to arrange such measurements right next to controlling apps on a single tablet screen. Apart from some minor flaws, the app is much better than the original one by Illuminati.