Table of Contents Show

Stitch Head (2025) is an animated feature film based on Guy Bass’s beloved children’s novel. A co-production between Gringo Films (Germany), Fabrique d’Images (Luxembourg), and Traumhaus, with animation by Assemblage Entertainment in India, the project brought together artists across continents, formats, and pipelines.

We spoke with Oliver Finkelde (VFX Supervisor), who guided us through the production — alongside Stéphane Lecocq (Production Design), David Nasser (Animation Director), Nico Rehberg (Lighting), Juliane Walther (Line Producer), and Viola Lütten (Producer).

Oliver Finkelde (Web | IMDB | Linkedin) studied at the Filmakademie Baden-Wuerttemberg and has contributed to large-scale productions at studios such as DreamWorks Animation, Sony Pictures Imageworks, Skydance Animation, and RiseFX. His credits include work on feature film franchises like Shrek, Kung Fu Panda, Madagascar, How To Train Your Dragon, and Wish Dragon. He works as staff at RiseFX and, time-permitting, collaborates with international teams on animation projects, focusing on character-driven storytelling and digital production workflows.

DP: Oliver, how did you get involved with Stitch Head and how would you describe the film to our readers?

Oliver Finkelde: While vacationing in Zanzibar, I was contacted by Juliane Walther, the line producer at Gringo Films, about Stitch Head. The studio was looking for an experienced VFX Supervisor with a strong background in AAA-quality feature films. Having worked on many major productions in the U.S., I was immediately drawn to the project — it felt unique, ambitious, and genuinely fun and the team was incredibly welcoming.

The story of Stitch Head is deeply touching and profoundly moving — filled with hope, love, and friendship. Its themes resonate strongly with me as a father. In addition the director’s vision and creative ambition were enormous — in my eyes, a real game changer for Germany.

DP: Can you give us a sense of scope? How long did the production run, how many people and studios were involved, and what did the international collaboration look like?

Oliver Finkelde: I will hand this one off to Juliane as she’s been part of the project since the beginning.

Juliane Walther: The actual image production, starting from the script, started in 2020 and took around five years. Before that came the earlier stages – financing, development, and scriptwriting, which added several more years to the overall journey.

If I’m not mistaken, over the course of production around 800 people contributed to the film in different phases. The size of the core team varied depending on the stage of production – from about 10 people in quieter periods up to 20 during peak times.

The team was spread across Germany, France, Luxembourg, Belgium, England, India, and the United States, with eleven studios in Europe and India involved in the image production alone. Beyond that, additional creative and technical partners from these countries played key roles in bringing the project to life.

DP: From your perspective as VFX Supervisor, what makes Stitch Head interesting in terms of how it was produced?

Oliver Finkelde: When producing in Europe, proficiency, productivity, and agility are key to ensuring that every cent ends up on the screen. The core team was intentionally kept small, which allowed us to make decisions quickly and enable all departments to work as efficiently and creatively as possible.

Production Design

DP: Oliver, production design sets the tone for everything. Can you introduce Stéphane, who led the design? What made his work crucial?

Oliver Finkelde: It was my first time working with Stephané, and I couldn’t have been happier. Stephané has an incredible eye and a remarkable sense for creating worlds that truly serve the story, adding depth, texture, and tangibility, and allowing the audience to become immersed from the very first moment.

Stéphane Lecocq (Linkedin) is Creative Director at La Fabrique d’Images, a position he has held since May 2016. His recent credits include Stitch Head (Artistic Director, Concept Artist, Moodboard Artist), Oops Noah Is Gone 2 (Production Designer), Funan (Color BG Supervisor, Moodboard Artist), and Bayala (Production Designer).Other projects there include Richard the Stork, Extraordinary Tales, Mullewapp, Song of the Sea, Maman est en Amérique, Tante Hilda, The Congress, Ernest et Célestine, and Le Jour des Corneilles.

DP: Stéphane, how did you approach the look and feel of Stitch Head? What references guided you in balancing a gothic atmosphere with a children-friendly story?

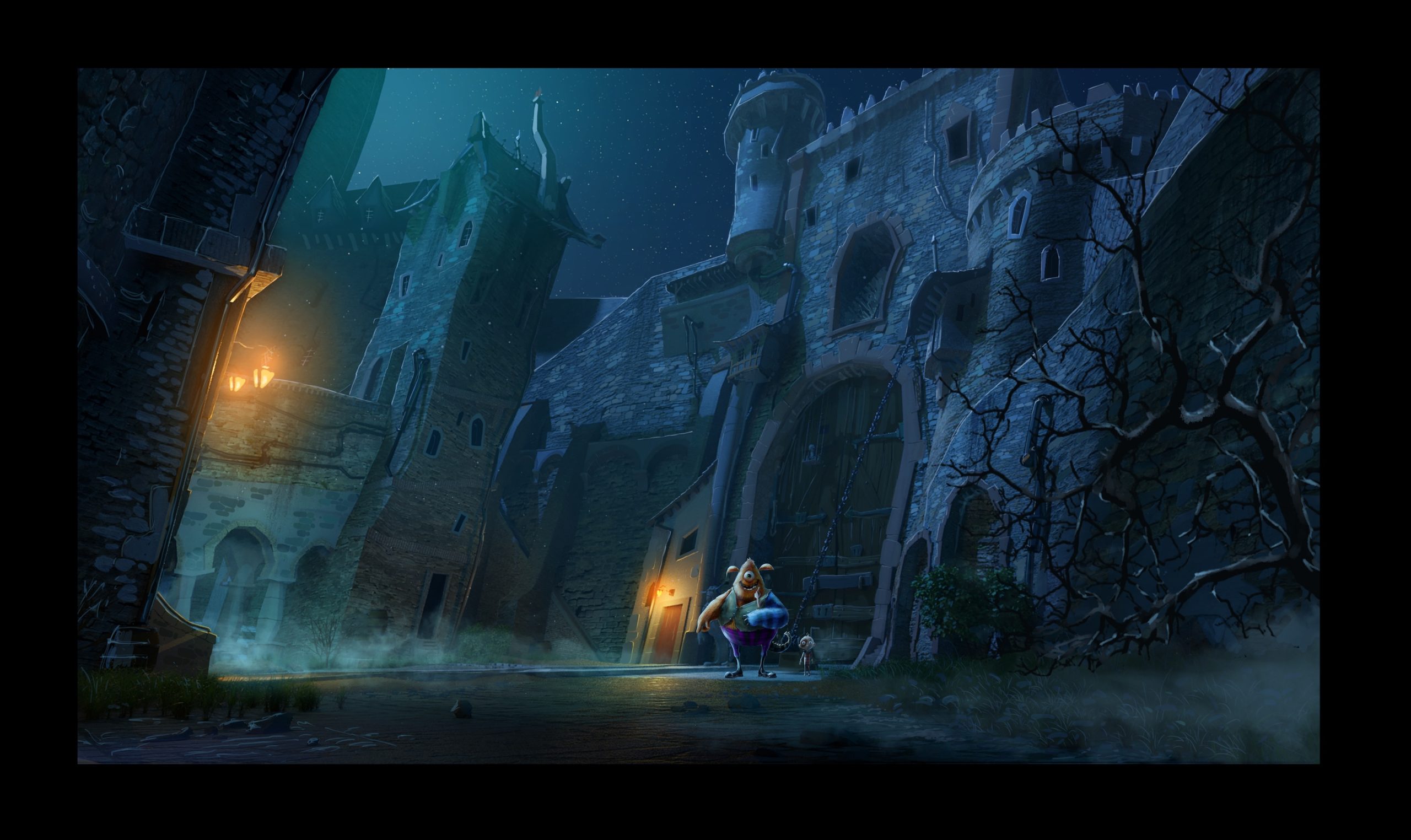

Stéphane Lecocq: The look and feel was a mix between the old school Hammer movies from the fifties like the bride of Frankenstein, and the more actual 3d cartoony movies. It was quite challenging to find the sweet spot between those 2, in order to make the movie an experience for the whole family I had to mix the dark tones of the castle, balanced with a friendly and cosy atmosphere with all the monsters. It’s still a comedy. Our director, Steve Hudson, is an encyclopedia when we talk about movie refs. So we tried as much as possible to incorporate them in the movie.

DP: Can you walk us through your workflow ? What tools and methods you used, and how you translated sketches into production-ready assets?

Stéphane Lecocq: My creative process always begins with sketches on photoshop, followed by a 3d model on Blender, which is my favorite 3D tool. I add some lights in the scene and then voilá. We can do so much now with those programs to speed up the process. Then I send my rough models to the teams (storyboard, set modeling etc…). It’s easier for them with all the references and the different camera views.

DP: When your designs moved downstream, what did you want people to take away from them?

Stéphane Lecocq: I was very picky with the “style “of the environments, where I tried to avoid straight lines, with every furniture and props a bit broken and bent..

DP: Which character or environment in Stitch Head are you most proud of?

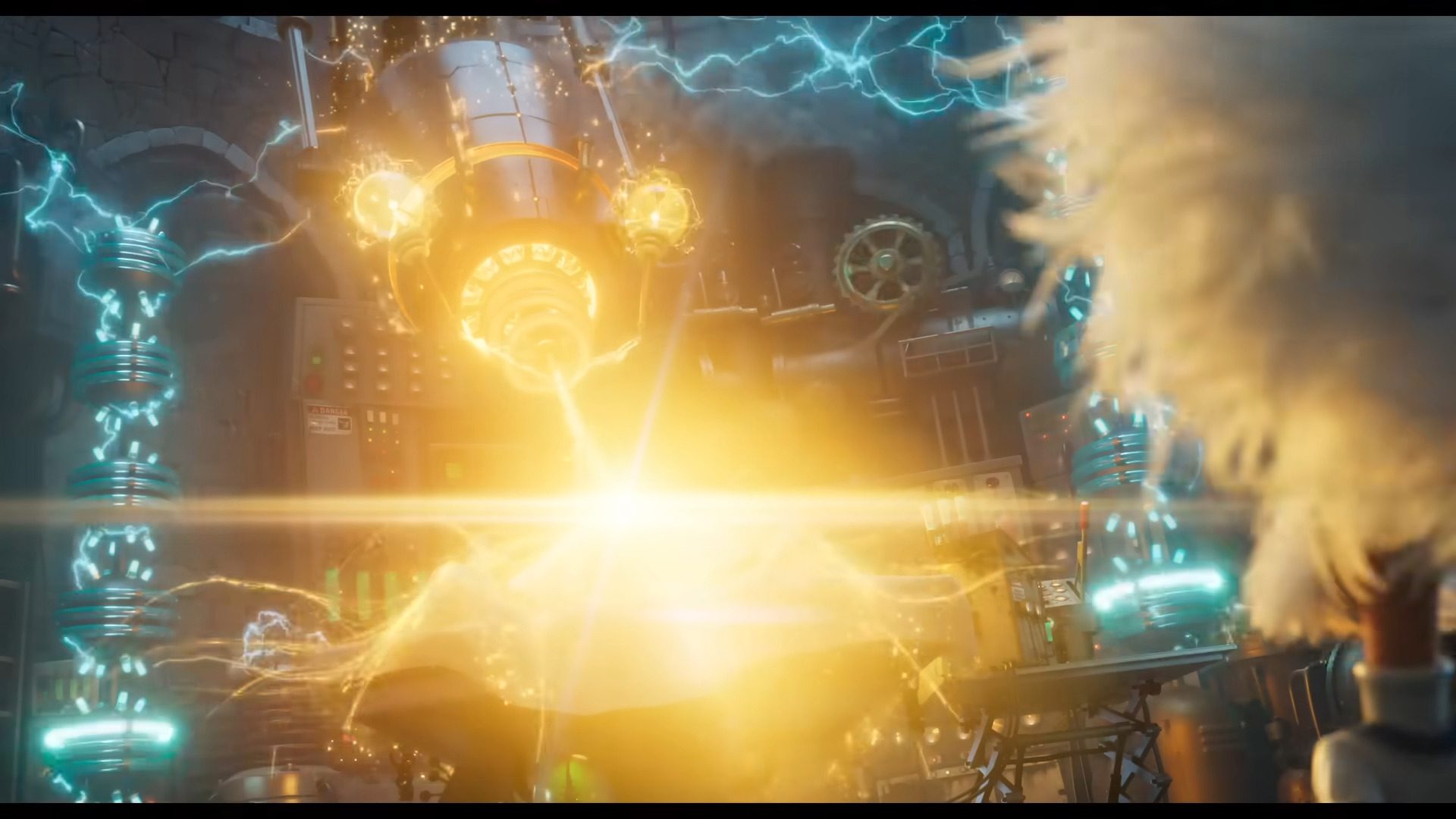

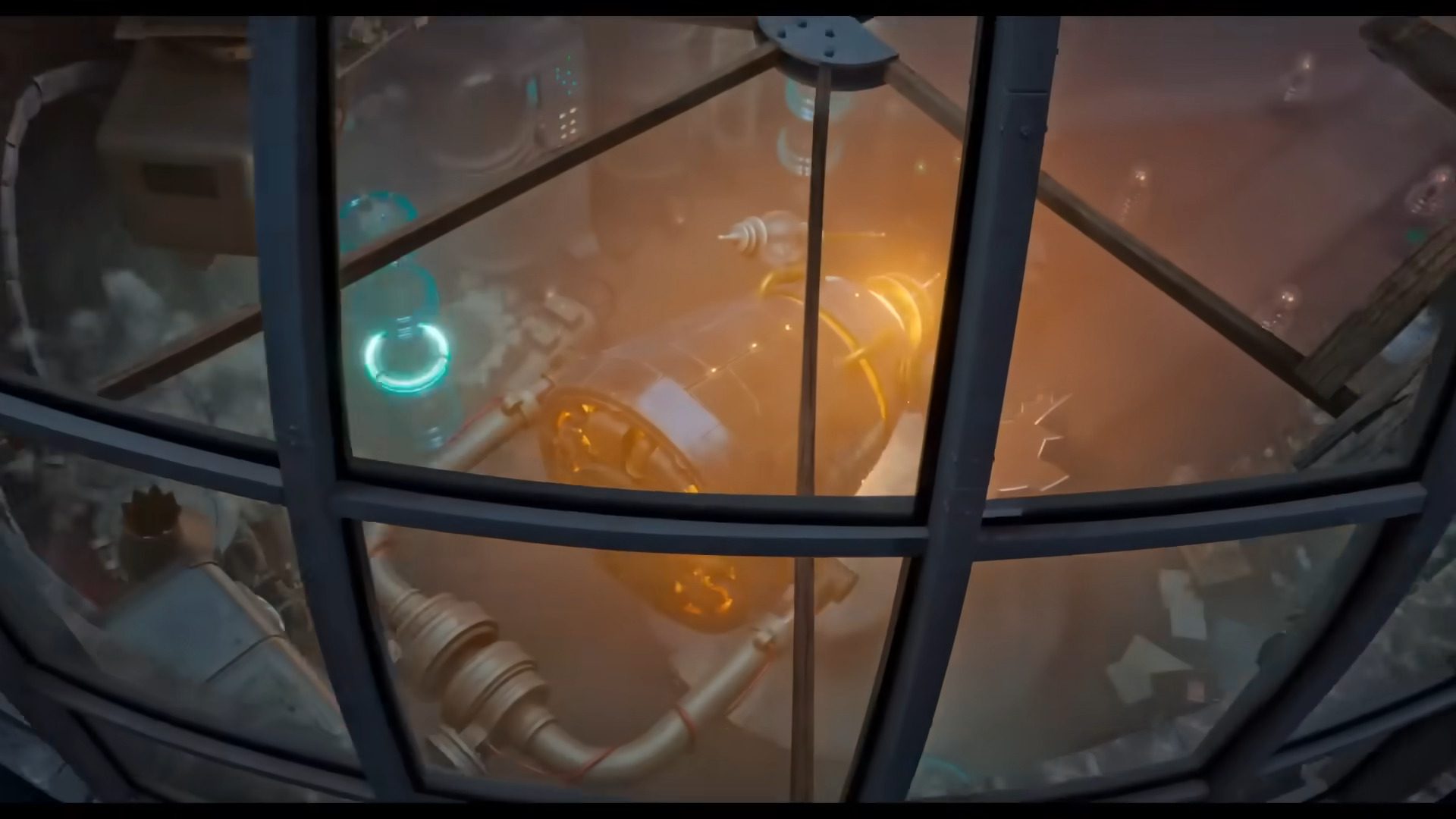

Stéphane Lecocq: Definitely the lab, with all the moving parts, with all the lights coming from the different devices, plus the FX parts. It was challenging to make this set work. But the result is great. The caravans also! It was really fun to design the charabanc.

DP: Looking at today’s technology: if you were to start Stitch Head now, would you consider a game engine like Unreal for design and visualization?

Stéphane Lecocq:I think nowadays, Unreal Engine can be a really powerful tool to speed up different process, like creating sets, skies and moods. The library of props is so huge. But for that, you also need a correct pipeline, and with so many studios working on a movie, it’s not an easy thing to set up. The future, with the rise of AI is not so peaceful. The way we handle production will change, and is already changing, at fast pace. I just hope that we will still continue to draw, and create designs by hand, and not only prompt with AI.

DP: Was there anything about this production design that posed unusual technical challenges?

Oliver Finkelde: What I love about animation is that anything is possible and nothing is ever unusual. Still the creative leadership worked closely together to ensure that Stitch Head’s world, the environments, characters, and overall design, translated beautifully into 3D. The goal was to capture the essence of Stephané’s artwork while keeping everything as manageable and production-friendly as possible.

With the color script always in mind as the guiding reference, a great deal of time was spent on planning and carefully managing complexity and levels of detail. Understanding the color script, layout, and working hand-in-hand with the director and production designer to know where to focus resources was absolutely key.

In terms of technical support Vishnu Ram at Assemblage played a key role in making sure shot production including deliveries to lighting were consistent and efficient.

Animation

DP: Animation gives these designs life. Oliver, can you tell us about David and the animation team, especially India?

Oliver Finkelde: As an animation veteran, David was the perfect fit to direct and mentor the animation team over at Assemblage in India. In the Animation department especially, being present during key stages such as team building and character exploration was crucial. Having the ability to divide time between Europe and India proved vital to the success of the production.

David Nasser (Website I LinkedIn I IMDB) is a director and animation director with a strong foundation in visual storytelling, honed at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), where he specialized in animation. Over the course of his career, he has held senior and lead animator roles at top studios across Europe, the UK, and the United States.

David’s credits span a wide range of acclaimed animated features and series, including Arcane, Despicable Me, Hotel Transylvania, Rio 2, The Chronicles of Narnia, and many others. He served as animation director on the Oscar-nominated film I Lost My Body, as well as Zombillenium, The Tiger’s Apprentice, and the recently completed Stitch Head. Currently, David is directing animation on the upcoming feature High in the Clouds, and is also co-directing the original animated film ADAM, which is in development.

DP: David, what was your first step in setting an animation style and making sure the animators followed it half around the world?

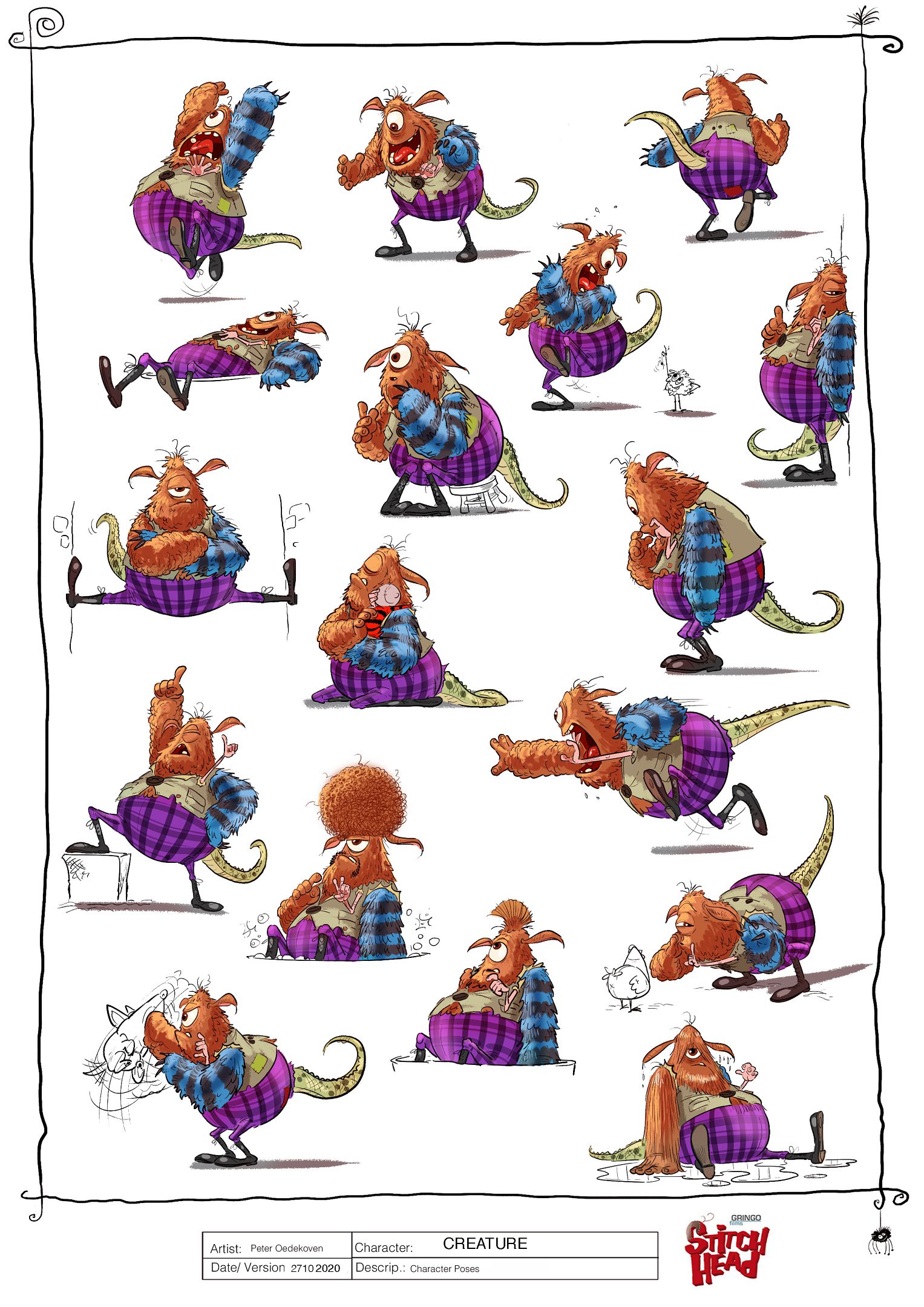

David Nasser: The first thing I look for are boundaries and limitations that help define the animation style. Most importantly, it starts with character design—it sets the tone and complexity of the animation. Some designs offer more range and freedom, while others demand a tighter, more controlled approach. When I see the characters, they immediately come to life in my mind, and I follow my gut.

Next, I gather everything else: the script, tone (comedy, drama), concept art, animatic, the director’s vision -and of course, budget and resources. That’s how I begin shaping the animation style… in theory.

In practice, there’s a lot more to it. You have to assess complexity, production time, and costs early on to see whether the vision is actually achievable. Dreaming big is great, but we also need to deliver on time -and consistently.

Beyond the artistic vision, my role as Animation Director connects many departments and people. I rely heavily on production support, supervisors, leads, and every single artist. Especially on international productions, clear communication is essential. To ensure consistency and quality – no matter where artists are based – we need a well-established workflow, strong motivation, and ideally, personal connection. Meeting people in person, when possible, makes a big difference. Just as important is creating a respectful environment where people can enjoy the process, feel valued, and grow through the experience.

Back to the style itself: this project, being a comedy-drama-creature tale, required a nuanced approach. Emotional moments called for subtle, more naturalistic animation, while the comedic scenes leaned into snappy timing and cartoony exaggeration. The monsters, who often appeared in groups, had to be more limited and stylized to manage complexity and technical constraints. The challenge was balancing these different styles while keeping everything in the same universe.

Together with the director, we curated reference materials, both animated and live-action, to help communicate the tone. From there, we began test animations, usually with a small team of 6–8 artists and a supervisor. These early tests helped define character performance and build a pose library, which helped to keep characters on model and supported consistency as new artists joined.

I build new teams for every project – sometimes up to 70 artists and more. It’s the hardest part, but also the most rewarding.

To keep the animation style consistent and stay connected to the team, I rely heavily on live reviews. Every artist presents their shot and receives direct, real-time feedback. I prefer to keep things simple and avoid too many layers between artists and decision-makers. It keeps communication clear and creativity flowing.

Motivation and team awareness are key. Artists should know what their colleagues are working on – it’s inspiring and helps align everyone creatively. Our director, Steve Hudson, was a huge help here. With his background in acting and voice work – and being the scriptwriter – he brought a contagious energy. He was an engaging presence and always available, which really lifted the team. The performances that came out of that were just fantastic.

DP: How did you coordinate such a large international animation crew, and what processes ensured consistency?

David Nasser: I definitely wasn’t alone. Coordination is a team effort that includes production coordinators, a production manager, and line producer. Together, we manage timelines, workflows, and resources. As Juliane already mentioned, having clear structures and a transparent workflow is essential. Both long-term goals and weekly targets should be visible to the entire team. I believe in giving artists ownership -it makes the whole team stronger and more reliable.

Animation supervisors and leads play a huge role. They help manage the team and ensure the creative vision is understood and executed correctly.

Steve and I would typically brief a new sequence each week in live meetings with the supervisors and teams. These sessions were where we shared references, direction, and intentions. Ideally, the supervisor had already assigned the shots, so the artists came prepared and could ask questions early on.

Artists would then pitch their ideas, usually with video references. It’s a quick and effective way for us to get a sense of where a shot is going and give initial feedback. Once that’s aligned with the director’s intent, they move into blocking. That’s when we really refine the performance, strengthening the character, emotion, storytelling, or comedy. After that, the review process shifts more to me. I guide the team through the final notes and help bring shots across the finish line. We do daily live reviews.

Beyond shot work, I try to hold short classes or ask artists to share tips and tricks. It’s a great way to boost morale, share knowledge, and keep things fresh. Celebrating wins, whether through screenings or positive feedback, also helps keep the energy up.

DP: Can you share a particularly complex sequence and how the team solved it?

David Nasser: There were quite a few complex sequences, especially the musical numbers. Some went surprisingly smoothly, with the team exceeding our expectations.

But one of the toughest was Stitch Head’s escape from the castle, when Freakfinder tries to take him away in the hot air balloon. That sequence had everything: drama, comedy, emotion, and physical action. Timing, continuity, and performance were all critical. Plus, it was technically demanding.

I’m rarely worried if we’ll finish something, there’s always a solution. The real challenge is when time and budget run tight. I try to shield the team from that stress as much as I can, while working with production and supervisors to find ways to make up for lost time, ideally without compromising quality. That’s when a team’s resilience is truly tested.

This sequence was one of those moments. But the team at Assemblage – from the supervisors to every single artist – was outstanding. Thinking back on it still gives me goosebumps. It was an incredible collaboration, and sad to see it come to an end.

DP: In your view, what’s the “heartbeat” of Stitch Head, the animation choice that best carries the story?

David Nasser: That’s a tough one. The film has so many characters and perspectives, each with their own emotional arc. Stitch Head goes through a “coming-of-age” journey. He realizes that what he’s been searching for was always right in front of him, but he had to explore the world to see it.

Creature – my personal favorite – remains pure, innocent, and full of love. He doesn’t change much, but he experiences the world in his own way and I just love how he is reacting to it.

Two moments always stay with me. First, when Stitch Head tells Creature his life story. It’s the first time Creature feels sadness. It’s sweet, funny, and deeply touching. Second, the scene by the river, when Stitch Head decides to go into the village with Arabella, leaving his “bestest-best friend” behind. Both are subtle and emotional – my favorite kind of moments.

From a more dynamic perspective, I’d also highlight the musical number “Make ’Em Scream.” It’s bold, theatrical, and one of my favorites and really captures the playful side of the film while serving the story. Overall, Stitch Head was a wonderful experience. Great story, great team. I truly hope we get to do this again.

Handing off to Lighting

DP: Lighting defines the mood. Oliver, how did you work with Nico to balance gothic darkness with a family-friendly look?

Oliver Finkelde: Stephané had previously worked with Studio Rakete, which was a huge advantage in building trust and ensuring seamless communication. Walking the Rakete team through the color script while also focusing on the emotional arc of the story and of Stitch Head himself was vital to making sure key shots landed as close as possible in the first round. The studio brings a great combination of artistic vision and technical expertise, which made their contribution indispensable, especially in complex sequences involving FX and crowds, such as the laboratory and circus tent.

When it came to the look, particularly in the night sequences, we were very intentional about guiding the viewer’s eye through careful control of saturation, values, and contrast striking a balance between family-friendly visuals and that subtle sense of “being on the edge of your seat.” During color grading, this became especially crucial: we wanted to preserve the film’s soul and visual integrity, whether viewed in a theater or later at home.

Nico Rehberg (Imdb | Linkedin) is a 3D freelancer based in Germany, specializing in lighting and rendering. He describes himself as someone who “loves to juggle with triangles,” and his film credits include Fast Five and Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows, among others, showcasing his involvement in large-scale studio productions. He’s also credited for German / European titles such as Lissi und der wilde Kaiser. In earlier projects, he worked on shorts and television productions, contributing in cinematography, editing, and production roles. His long career (active since the late 1990s) spans commercial, feature, and broadcast work, all grounded in technical artistry in digital image creation.

DP: Nico, what was your lighting concept for Stitch Head? Which moods and palettes guided you?

Nico Rehberg: The look and feel for each sequence was guided by a very detailed mood board done by Stéphane and his team. We had at least one painted frame for each sequence. Combined with a briefing this gave a good direction for the desired final picture. Thus our job was mainly to translate this into 3d lighting and compositing while keeping everything on time and in budget. I know this does not sound very artistic, but in the end this is Steve’s and Stéphane‘s vision, crafted in close collaboration with Oliver, we are trying to bring to screen, not mine. I just fill in the gaps and give advice.

DP: Which tools and render engines did you use, and why?

Nico Rehberg: Our choice of tools was rather old school. Everything was centered around Maya, with Arnold as the renderer and Yeti for the hair and fur generation. Compositing was done in Nuke and Royal Render managed our farm. We have been using this setup for many projects now and really like how rock solid and mature all tools are. Technical render issues are nearly non-existent and render times are very predictable.

Generally I try to avoid overengineering our pipeline. Our workflow is simple and direct. We light shot by shot with simple tools to handle all the tedious and repetitive task. Even through all the input data to lighting is cached, we still enable the artists to use every tool available in Maya. Moving things around, tweaking shaders, fixing broken geometry or floating characters, adjusting FX – in our productions lighting is often more than just putting lights in a scene and setting up layers.

DP: What was the most challenging sequence to light, and how did you solve it?

Nico Rehberg: The most complex light setup was definitely the one in the laboratory. A lot of blinking lamps, lightning arcs, coils, glowing bulbs, luminous liquids and the big gun itself. The lighting was required to be very dynamic and directable. From Stéphane we had a detailed breakdown of the different stages the laboratory goes through during the reawakening sequences.

Since I try to avoid to animate lights in 3D as much as possible one artist, Phillipp Wibisono, broke this all down into a lot of layers and light AOVs which we then reassembled and animated in Nuke. This allowed much faster turnaround times while orchestrating these sequences. But it still meant a lot of layers and hundreds of lights, which sent the render times through the roof.

On top of that the lab features in the 2 longest shots in the movie. One with 1290 frames and the other 1436 frames (60 seconds!). We only had room for one try in rendering. There was no time for a re-render. The second shot was actually the last shot we rendered, occupying the farm for more than a week, right before delivery.

DP: Achieving visual consistency across teams and departments is notoriously hard. What steps did you take to make sure the look stayed cohesive all the way through?

Nico Rehberg: I think a good art direction is key here. A detailed mood board and precise briefings counter the fact that shots are often produced in a seemingly random order, but still have to fit together later. We had Stéphane, Steve, and Oliver on board until the very end, so we did reviews on the key shots in lighting and all the compositings with them. Furthermore I did a lot of the lighting setups myself and had the luxury to work with a small team of artist over a longer period of time instead of rushing the production.

My goal in lighting is to create a good basis for our compositing team around our Supervisor Tim Liebe. Often consistent lighting output is more desirable than perfectly lit shots that don’t fit together or leave no room for comp. And since we handled all the lighting and compositing here at Rakete we could often just talk about things.

DP: Which scene are you most proud of, the one where light really tells the story?

Nico Rehberg: I don’t think there is a one shot to name. Light is but one part of the experience. There are very beautiful moments that are lit with only 2 directional lights and a dome, while other shots with tons of lights and lots of cheats to make them readable fly by in 14 frames.

But I’m very proud of the overall movie. I think we managed to really support the story, bathe the world of Stitch Head in fitting light and deliver high quality images. And all that within our time frame and limited budget.

DP: With comp workflows evolving fast, from OCIO color pipelines to more open interchange Formats. How did those tools shape your work on Stitch Head, and how do you see them changing lighting/comp production in the future?

Nico Rehberg: A lot of these newer big standards require changes and investments throughout the whole production pipeline of a project. And since our productions are usually split across multiple studios it is not easy to change. We have to find the least common denominator and agree on workflow very early. For example Stitch Head‘s toolchain was fixed around 2020. These new standards open a lot of possibilities, but they are not turnkey solutions. They increase the needed technical expertise at a studio a lot. We have to decide if they really fill a hole in our workflow or solve an existing problem.

OCIO is by now very well integrated in most programs and the basic workflows are more or less standardized. But USD on the other hand requires a vast amount of planning, restructuring and development. It is also still evolving rather fast. And although it seems to be inevitable in the future we haven’t really embraced it yet.

I am much more looking forward to the small brilliant things popping up that will make our lives easier. Like Cryptomatte, which was a game changer. Or Arnolds denoising. It solved a lot of our render problems.

DP: Oliver, how did lighting and compositing feed back into your supervision role, especially across distributed teams?

Oliver Finkelde: After Stephané walked the Lighting and Compositing Supervisor through the color script, we reviewed the key shots in context meaning together with their connecting sequences during the first rounds. This approach ensured visual continuity and strong support for the story arc before moving on to the rest of the sequence. Our goal was to have shots approved within roughly three review rounds. During lighting dailies, we also discussed which refine tasks made sense to hand off to Compositing, allowing us to keep shots moving efficiently and make the most productive use of the render farm.

Handing off to the Line Producer

Juliane Walther (Web | Linkedin | Imdb ) is an animation line producer based in Leipzig. She studied at the Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg, where she focused on 2D, CGI, and stop-motion production. Her filmography includes short films such as C4RE and The World We Live In, as well as the Creature Pinup project. Walther also worked on the feature animation Latte and the Magic Waterstone and has been involved with production at Gringo Films GmbH. (only StitchHead)

DP: Behind all this creativity is production reality. Oliver, can you introduce Juliane, who kept the budget and schedule on track?

Oliver Finkelde: Sequences are never truly finished at some point, they simply have to go. Juliane was instrumental in keeping us focused on what mattered most in terms of schedule and budget. For me, maintaining a close collaboration with the line producer is always essential, and I couldn’t have asked for a better partner when it came to balancing art, schedule, and budget.

DP: Juliane, how did you structure the production schedule across Europe and India?

Juliane Walther: Over the course of five years of production, we had to coordinate a complex network of partners and independent studios – eleven of them dedicated solely to creating the final image. Different cultural approaches to work and communication, multiple time zones, and eventually the COVID-19 pandemic turned the production into both a logistical and a human challenge. The balance between creative ambition and production reality had to be constantly maintained: building structure without stifling creativity, while keeping workflows, technical standards, and overall quality consistent throughout the entire production.

That balance relied on clear organization and a good deal of sensitivity. We had to find time slots where teams in Germany, France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and India could actually talk to each other., sometimes even shifting working hours to make personal dialogue possible. Communication was about much more than exchanging information: it meant building trust, reading between the lines, and understanding the different dynamics of each team. Regular calls, from daily check-ins and reviews to several weekly production meetings kept the collaboration alive. And sometimes, it simply took getting on a train or a plane to be there in person and strengthen the sense of connection that video calls can’t fully replace.

For such a large network of contributors to work smoothly, clear structures and binding workflows were essential. From the planning stage onward, tasks were divided to keep dependencies as low as possible, allowing each step to be completed and handed over cleanly to the next department – reducing friction, overlap, and rework. The planning itself was continuously fine-tuned and adapted to the realities of production to stay flexible to new demands. Defined communication channels and established procedures ensured that questions and issues didn’t linger but were resolved quickly. Quality checks in the studios were closely monitored to maintain a consistent visual and technical level across the entire film.

For planning and tracking, we needed a tool accessible to all partners – of course we used ShotGrid. It became the central hub of production, containing all relevant data on assets, shots, and milestones. Everyone could see the current status in real time, track progress, and identify potential bottlenecks early. It kept everyone connected across all studios, time zones, and departments and helped maintain a shared understanding of where the project stood at any given moment. Beyond ShotGrid, we relied on structured spreadsheets, milestone plans, visual diagrams of the production status, several tracking sheets, and detailed production notes – all to ensure transparency, clarity, and traceability in everyday work.

In the end, all of this was above all teamwork – built on trust, openness, and a shared sense of purpose. Across borders and time zones, transparency was key so that everyone knew where the project stood and how their individual contribution fit into the bigger picture. Five years is a long time – teams, technology, and processes evolve, which makes it all the more important to keep motivation and cohesion alive. And sometimes, when all plans reached their limits, it simply came down to willpower, because otherwise, a project like this just wouldn’t get made (smiles).

DP: What was the toughest challenge in managing this co-production?

Juliane Walther: One of the toughest challenges was balancing creative ambition with production reality. When vision and production responsibility come from the same person, expectations can shift quickly – and it takes structure, diplomacy, and constant communication to keep everyone aligned. Translating artistic goals into achievable production steps without losing the creative essence became an ongoing exercise.

Adding to that complexity was the constellation of studios involved. Some of them had collaborated successfully on previous projects, which helped – there was already a shared understanding and rhythm. But for this film, we brought in several new partners, both large and small. Each studio came with its own expertise, experience level, and production culture. Bringing everyone onto the same page – creatively, technically, and in terms of pipeline – required patience, coordination, and a lot of mutual learning.

The film itself also came with its own set of complex creative and technical challenges. Just to name a few: our beloved OWGGAGOFFAKKOOKKK, or “Oggi,” with his tangle of dreadlocks; Ermintrude beneath glass and water, accompanied by her fish and moving air bubbles; the crowd sequences; the burning and collapsing circus tent; the beautifully abstract dance sequence that proved especially challenging for animation and the laboratory, which became quite a challenge for the lighting department. Each of these moments pushed us to explore new solutions, workflows, and creative approaches – and to find ways for all studios to contribute seamlessly to the same cinematic world.

What made it possible was the dedication of a truly great team – one that stayed motivated, kept looking for solutions, never gave up, and always tried to move forward together.

If I could, I would name many more team members who did an incredible job bringing this film on the screen. But talking about managing a big thank-you goes to our production team at Gringo Films. At peak times our production team included up to eight production managers and coordinators: Alexander Erkens, Larena Schwarzenberger, Dario Ramm, Dorothea Mersmann, Belen Heydt, Sandra Fendauer, Ester Vicente Ballester, and Marco Muñoz. Each was responsible for a specific department and brought valuable expertise to the table, which allowed me to rely on them completely and made for a professional and trusting collaboration.

I’d also like to mention my esteemed colleague Alexander Erkens, who together with our Animation Director David Nasser and Larena Schwarzenberger oversaw the animation department for more than 14 months. Their dedication, leadership, and teamwork were essential in keeping one of the largest departments running as smoothly as possible.

DP: How do you balance the creative team’s needs with financial constraints?

Juliane Walther: Balancing creative ambition with financial realities is a constant negotiation. From my point of view transparency is the key: everyone, from the creative team to the production partners, needs to understand and see where the limits are and why certain decisions have to be made. Once the “why” is clear, compromises are easier to accept and priorities become clearer. To make sure as much of the budget as possible ends up on screen, you have to choose your battles wisely.

I always try to start from the creative perspective: what is the core of the idea, what emotional or visual effect are we trying to achieve? Once that’s clear, we look for ways to make it happen efficiently – through clever use of existing assets, optimized workflows, or simply choosing the right moment to say, “Let’s render that once we’re sure.”

For example, we wanted the circus crowd to feel big and alive, but we also had to be smart about it. So we worked with a small set of base models and created as many variations as possible by changing accessories, clothing, and skin tones to make it look rich and diverse while keeping things manageable. Early pre-production tests and renderings quickly proved that this approach can work.

Of course, not every wish can be fulfilled, that’s part of the process. Already at the storyboard stage, some ideas had to be let go. There’s a limit to how many challenges a team can carry at once. In theory, everything is possible, but everything takes time, money, and motivation. In those moments, I prioritized maintaining consistent quality throughout the entire film.

With open communication, trust, and a shared understanding of the film’s priorities, limitations can turn into collaboration. That’s when the budget stops being a constraint and becomes the framework in which creativity truly thrives.

DP: If you had to explain your role to a film student, how would Stitch Head be your case study?

Juliane Walther: If I had to explain line producing to a film student, I’d say it’s about building bridges between creativity and logistics, between vision and reality, between all the people who make a film come alive. On Stitch Head, that meant coordinating an international team, keeping communication flowing across time zones and cultures, and turning artistic ideas into something that could actually be produced within given financial conditions and a fixed deadline.

A big part of the job is organization, yes, but even more it’s about understanding people and helping them work together toward the same goal. You’re constantly listening, translating needs, solving problems, and keeping an eye on both the big picture and the small details that make it work. The best moments for me are to find solutions with the team and when a plan comes together – when all the coordination and chaos somehow turn into a scene that works beautifully on screen.

Lighting & Comp

Viola Lütten (Linkedin | Imdb) is a Line Producer and has been working since 2006 at Studio Rakete GmbH in Hamburg. Her film credits include The Amazing Maurice (2022), Ooops! The Adventure Continues (2020), Luis and the Aliens (2018), the Niko Cinematic Universe (2008, 2012, 2024). Viola studied at the Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg in Ludwigsburg.

DP: What was your system to keep an overview of all the shots, especially in lighting and comp, where details change constantly?

Viola Lütten: Definitely ShotGrid, as the main source of information on the status of each shot. Luckily all other partners relied on Shotgrid as strongly as us, so the databank was constantly in a fresh and up-to-date state. The production period for LRC was in the end stretched over 17 months.

In the beginning Juliane had drawn up this huge plan, where it was determined what sq will be ready for us in which week. That looked good in theory, but in reality there were so many unexpected challenges and hurdles, that we at Studio Rakete kept our focus only on the foreseeable future, like the next six weeks or so. That made it easier to keep an overview of the current and the possible future workload.

DP: What were the biggest challenges in terms of ingesting upstream and staying on schedule?

Viola Lütten: It is always a challenge to estimate the incoming workload, when you are so dependent on others to deliver. I kept a close look on the incoming frames per week and the needed average for the farm to keep it humming on a constant basis. We have been working with the same core team in Lighting and Compositing at Studio Rakete for quite some time, so I know how much shot input we will probably need for each individual artist per week to keep them busy and happy.

I may have communicated a slightly higher needed overall input to our partners, just to be disappointed as expected and get exactly what was necessary. I absolutely hate to lay off or postpone artists or ask for overtime – so the planning was very conservative.

We worked for a long time on this production with small teams. In the last three months we almost doubled the size of the Compositing team for the final sprint. No postponing or overtime involved. It also helped that Studio Rakete is an established animation studio with twenty years of experience and a strong administrative and technical team, so it was not necessary to build up new structures, but everyone could concentrate on the work.

DP: Which shot is your personal favorite, the one where you felt all the pieces came together?

Viola Lütten: Each shot that is approved becomes my personal favorite (laughs).

DP: Lighting and comp often sit at the end of the pipeline, where every upstream mistake shows up. How did you build trust and communication with upstream so the problems didn’t just pile up on your desk?

Viola Lütten: Isn’t it part of my job description, that problems will pile up on my desk? Just kidding. As mentioned previously the production had this huge sq planning for the whole production period, which was a great starting point for the weekly needed output and input of shots and frames. As in every production things didn’t quite go as planned.

The good thing was, that it did not result in blame games, but a rather great collaboration between all partners to find the hidden sq gems that can be moved up in priority and fill looming gaps. Studio Rakete had also worked with Fabrique d’Images on several feature projects in the past – so there was a lot of trust and respect on both sides. So not all partners were new.

Nevertheless my production team, Carrie Schilz and Marcel Tie, and I kept a close eye on the notes in ShotGrid to anticipate possible frustration flare-ups from our artists and sent a preventive “I see your pain, but please answer nicely”-text to them, before they reply to a particularly unnerving note in ShotGrid. It also helps that many artists still work on site at Studio Rakete and that there is a couch in my office: it is very comfy and everyone is welcome to sit down and share their troubles. Even the cleaning staff makes use of it.

DP: To all of you: what’s your favorite shot or moment in the film?

Oliver Finkelde: The hot air balloon sequence. It’s visually absolutely stunning.

Juliane Walther: Among several proof-of-concept shots, we specifically chose the sequence where the hot air balloon rises over the wall. It served not only to test technical challenges, but also to explore the emotional impact and overall mood of the film and also to create an early “wow” image that would inspire both the team and our partners.

From the very beginning, we aimed to include proof-of-concept shots as early as possible, to identify potential issues before the start of shot production and to refine workflows for the later stages so that the actual shot production would run as smoothly as possible. Of course, problems always come up 😉

During Pre-Production we had a dedicated quality assurance team at Daywalker Studios for this purpose, ensuring that the ongoing production remained unaffected. In parallel, it also allowed us to test the pipeline early on and make necessary adjustments.

Juliane Walther: Also the Shot when Stitch Head is on the roof of the glass dome. It’s raining and he tries to catch the lightning with the umbrella – I already loved this shot when I saw it in the moodboard.

Viola Lütten: I especially liked the shot at the end, where the crocodile-gorilla-monster breaks through the glass window in slo-mo. The shot has 1.436#, so when that one got its approval we had suddenly 1,1% more of the whole movie done.

Stéphane Lecocq: The lab sequences, and the village set, which looks really amazing.

Nico Rehberg: I revel in the long shot flying up the mountain into the lab at the beginning and how it turned out. It looks so seamless now, but is made of 3 different shots, multiple light setups that blend into each other, sets that don’t really fit together, tons of layers, masks, comp, spit and duct-tape. We could only render it once in 3D, and when a comp version was sent to the farm all the other artists knew the farm would be blocked for the rest of the day.

DP: What’s one lesson you’ll carry into your next project?

Oliver Finkelde: Review and celebrate the beautiful work of departments more on the big screen. It’s so inspiring to see all the love and details that often get lost on the smaller screen.

Nico Rehberg: Don’t be afraid. There were some rather bold sequences in the animatic. More challenging than we usually like. But Steve pushed them through and with some careful planning they turned out to be less complicated for us than I thought. In the end they present some of the most fun parts of the movie and it would have been a shame to not have them in there.

Juliane Walther:To move into 3D even earlier during the storyboard phase. It’s easy to get misled by the simplicity of a 2D storyboard, things can look perfectly fine on paper but reveal major challenges once you start translating them into space, movement, and lighting. And testing and rendering early as possible. Even on a smaller scale, it helps to spot problems before they grow and saves a lot of stress later in production. In short: the sooner you test, the smoother it can be finished.

DP: If you had to give one piece of advice to newcomers who want to work in your role, what would it be?

Oliver Finkelde: Nature is the best teacher. Observe, listen and keep trying. Failing is part of the journey.

Nico Rehberg: Make a realistic plan before you start and stick to it. Be consistent in your output. Don’t relax or try to be too perfect just because the deadline is still far away. If you can not stick to your planned output in the first month, the next month will be worse and at some point you will start to sacrifice quality for speed. Crunch time can be avoided!

Viola Lütten: Please do your job properly. Don‘t half-ass it. Poor planning is the most avoidable cost driver.

Juliane Walther: Communication means a lot and there’s no such thing as the perfect plan. Plans change. People change. Productions evolve. What really matters is how well you communicate, adapt, and keep everyone moving in the same direction. In production you can’t just follow a schedule; you have to listen, translate, and connect people so the project can keep flowing – even when things shift. In the end, it’s less about controlling chaos and more about guiding it.

Stéphane Lecocq: To have precise designs, storyboard and moodboard, with attention to every details, don’t be afraid to have multiple angles for one ref, the more the teams will have, the easiest it will be for them.

DP: What’s next for you as individuals and as studios?

Oliver Finkelde: Looking ahead, I’m focused on wrapping up a VFX show at RiseFX while continuing to explore new rigging and animation approaches in Houdini. With Stitch Head about to be released, I want to express my gratitude to Sonja and Steve from Gringo Films, and to Juliane, for bringing me on board this incredible journey, their bold, out-of-the-box vision and approach for the project. Thank you to the whole Stitch Head team, you are amazing and of course, my deepest thanks go to RiseFX for their unwavering support.

Stéphane Lecocq: Art directing two other productions, still at fabrique d’images.

Viola Lütten: Studio Rakete is very happy to work on the sequel of „The Amazing Maurice“, which is currently in production.

Nico Rehberg: After the movie is before the next movie. Or actually right in the production of the next movie. So I will stick around at Rakete and make sure the next movies look just as appealing as Stitch Head.

Juliane Walther: I’m taking a short family break and giving new ideas a little time to grow in the background. The next project is never too far away.