Thunderbolts*, directed by Jake Schreier, arrived in theaters May 1st, 2025, following a lineup of Marvel operatives turned uneasy team. It blends grounded espionage thrills with comic‑book spectacle—think cloak‑and‑dagger meets superhero showdown.

Ryan Wilk is a seasoned VFX Producer at Digital Domain with over 15 years of experience managing visual effects for major blockbusters. His credits include high-profile titles such as Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021), Black Widow (2021), and X-Men: Days of Future Past (2014).

DP: Ryan, Thunderbolts* doesn’t exactly “whisper” visually. When Marvel called, what was the scope of work that landed on your desk—and what made you say “yes”?

Ryan Wilk: Digital Domain has collaborated with VFX Supervisor Jake Morrison on a few projects, so when he asked us to join the show, it was a no brainer for us. The scope of sequences this time around were a bit less flashy or grand than our usual fare (at least by Marvel standards). We were asked to help on two primary sequences, the vault fight and elevator shaft escape. Both sequences are quite grounded in their action (think Jason Borne rather than Captain America), but there was still quite a lot of VFX lifting to be done, it just may not be obvious to the viewer initially.

DP: Marvel films have a reputation for being VFX-heavy, but also iterative. How early was Digital Domain involved—and how much changed between first concept and final comp?

Ryan Wilk: We started our asset builds in the spring of 2024, so pretty early on. We then got news that the studio wanted to show a good chunk of our sequence at Comic-Con, which landed in July 2024. This really turned up the heat, but the silver lining is we got to finalize quite a few of our assets and successfully establish the visual vocabulary of the Ghost phasing effect. Please don’t ever tell marketing this, but the Comic-Con push ended up really helping us establish things for the final film.

In regards to things changing between concept and final comp, usually, that is quite the journey on Marvel films. But this time things were fairly stable on our sequences. Of course, there were changes and creative exploration, but even if you go back to the original previs and stunt vis, they are quite similar in spirit to the final edits. Our previs team actually collaborated closely with director Jake Schreier, providing a clear visual blueprint early in the process, with a focus on fast and iterative development that supported his creative vision. This included mapping out the continuous progress of an early version of the elevator sequence.

DP: This vault isn’t your average storage space—more like a brutalist trap disguised as a filing cabinet. When you first saw the previs, what was your reaction to the creative and technical ambition of this sequence?

Ryan Wilk: Early in the bidding phase, when you see a sequence like this you always ask yourself “this is cool, but how much can they actually shoot”? Typically on Marvel films, our first impulse is to build everything from floor to ceiling. Be prepared for all CG shots. Make sure those walls are ready for destruction in case Hulk comes crashing in for a cameo (joking, that was never mentioned).

But on this film from the beginning, creatively (and budgetarily), the filmmakers had a plan to shoot these grounded action sequences, introduce the primary characters of the film and use VFX to really punch up the intensity and dynamics of the fight. And that held mostly true. We built out the vault floor fully in CG, along with some hero props and boxes. But we didn’t do a floor to ceiling build. For the extensions needed (hallways and higher ceilings), we used a DMP with a Nuke projection setup.

DP: Give us a sense of scale—how many shots did Digital Domain handle for Thunderbolts*, how big was your team, and how long were you on the project?

Ryan Wilk: We ended up producing 160 shots in the final film, and around 200 if you factor in marketing versions. We started on the show in Spring 2024, so almost an entire year. Team size varied across the schedule, but about 200 people touched the show in one capacity or another.

DP: The vault sequence manages to stay physical, while hiding hundreds of digital tricks. How did you approach the VFX so that it never shouted “look, we’re CG”?

Ryan Wilk: To stay grounded, our mantra became less is more. From spark hits to explosions, we would often start big and find ourselves dialing things back before approval. In cases where a heavier CG hand was needed, i.e., full digital doubles, we iterated heavily in animation to make sure the physics and motion of the characters didn’t jump out as implausible. And our hard surface & digi-double assets were top notch, so our CG renders really integrated seamlessly into the final product (with some help from comp, of course).

And finally, we could always go back to the plates. Even when replacing a character, we had a live-action reference to dial towards. The filmmakers stood by the photography they captured, so we were not pushing things around unnecessarily.

DP: Did real-time tools like Unreal Engine or LED wall setups play any part in your VFX planning, or was this all traditional plate-based post?

Ryan Wilk: Traditional plate-based post for our sequences.

DP: That vault set was 100 feet long. You extended it digitally with vents, walls, and connecting hallways. Can you walk us through how you scanned, rebuilt, and extended the space?

Ryan Wilk: Production used LiDAR to capture the set, which we then cleaned up and used for our needs. The hallways, vents and upper walls were extended using a Nuke projection setup, while the floor and key props were built out fully in CG. For the elevator environment, we also started with LiDAR and texture photography from the live-action set, but ended up tweaking the lookdev a bit to get the final look.

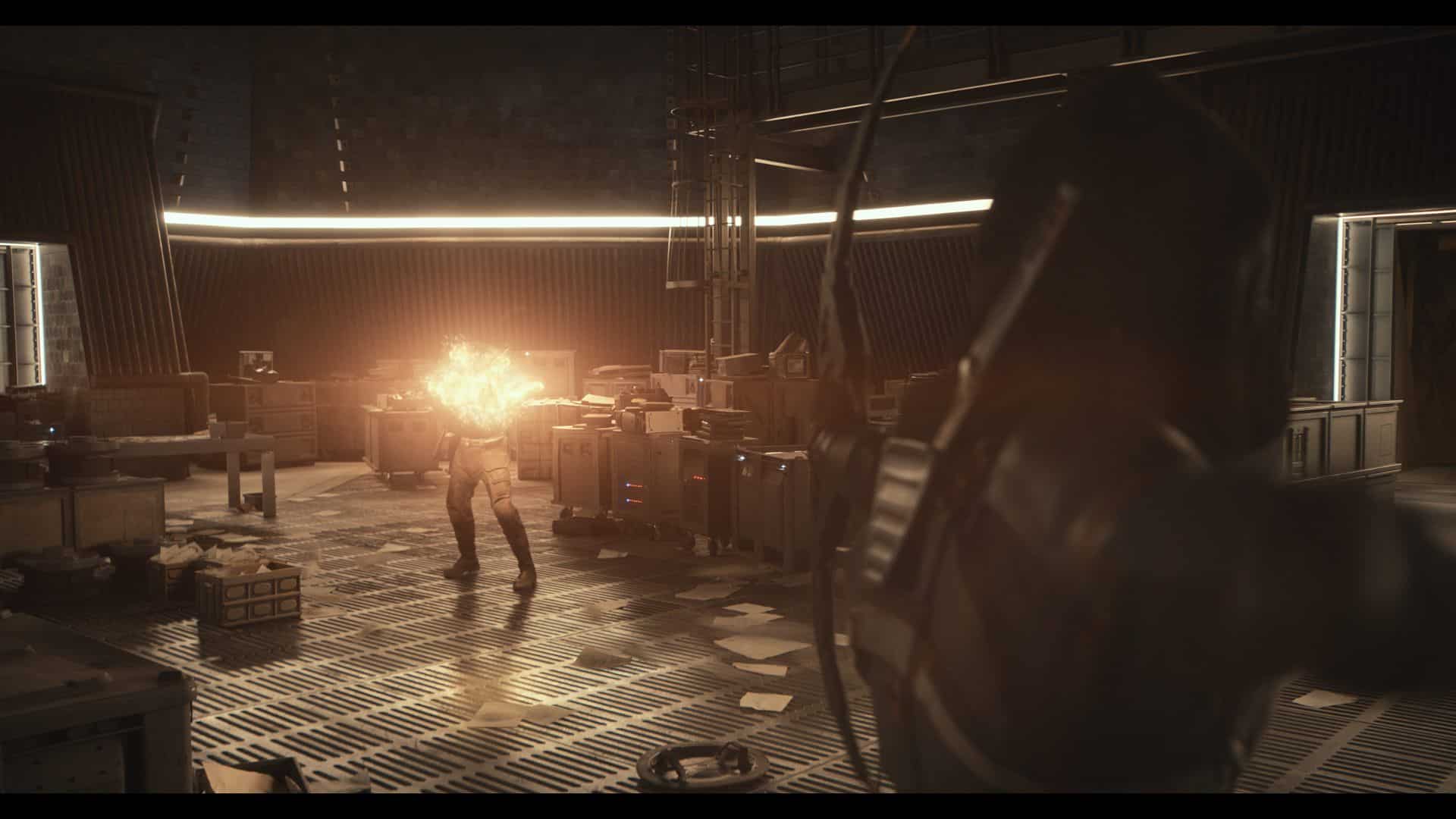

DP: Paper flying, sparks flaring, boxes tumbling—what was simulated and what was practical in the vault chaos?

Ryan Wilk: The primary vault fire flood (when the vents expel fire downward) was fully simulated in Houdini. We also simulated boxes, paper, and small debris to help with the realism. Ron Howard’s “Backdraft” was a great film for reference and inspiration for our explosions and fire.

We also did the explosive arrow simulations that hit Walker’s shield. In both cases (shield and flood), it was a matter of iterating to find the right balance of scale, density and timing to remain believable.

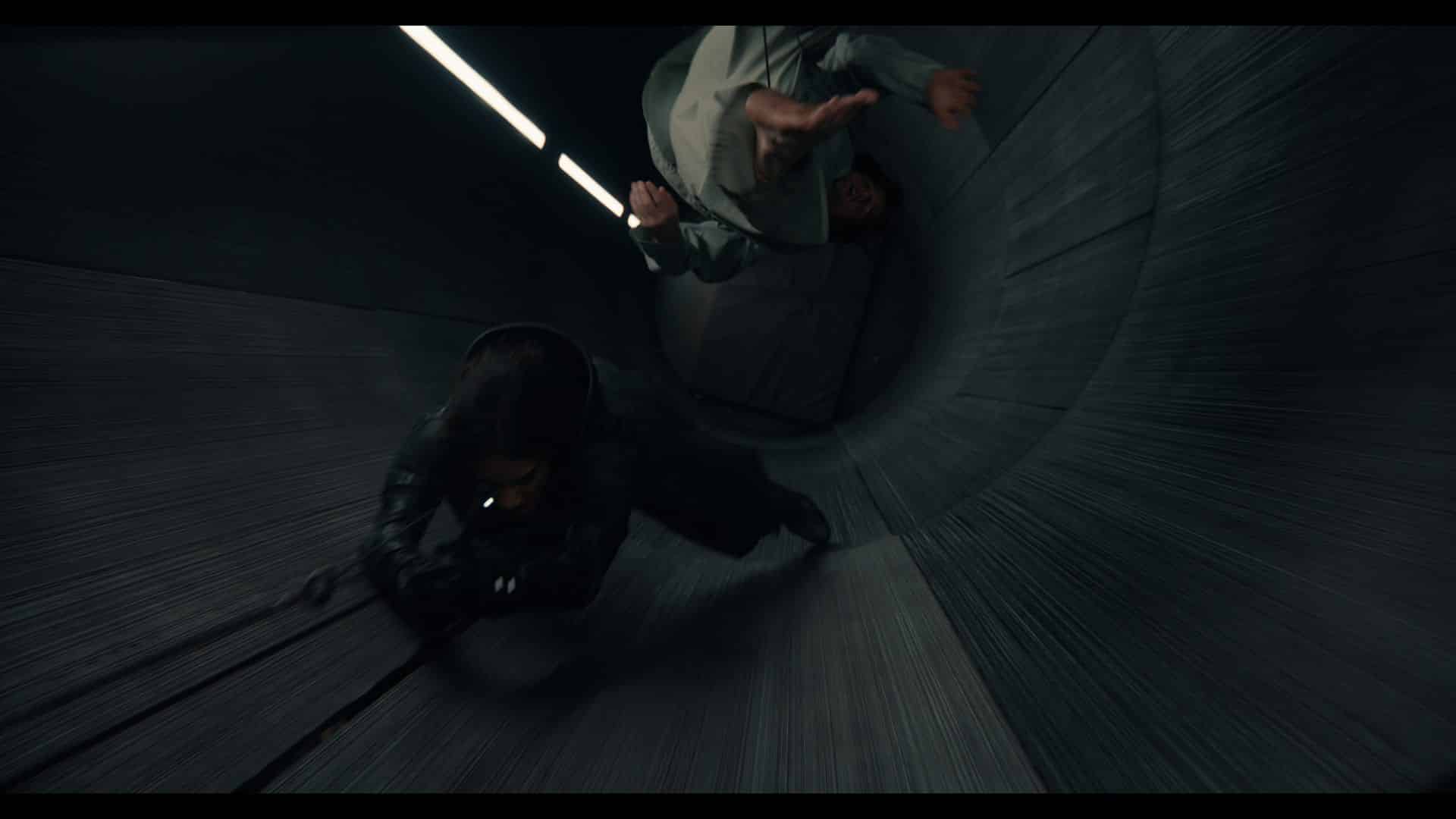

DP: In the Yelena throw shot, you combined Florence Pugh’s face with a stunt performer’s full-body take. Can you break down how Charlatan evolved for this? And how hard was it to keep hair and costume alignment believable?

Ryan Wilk: This was probably our trickiest shot. To get a seamless handoff, it really took all available tools we had. We started with an articulate track of the stitched Yelena performance and rendered her digital double with hair and cloth sims. Using our proprietary tool, Charlatan, we completed a face replacement utilizing other plates and takes of Florence as source material.

And lastly, our team had the idea to feed the Charlatan tool a hero frame and target frame for Yelena’s body itself, and the tool attempted to generate content to fill the gap. All of the elements (plate, CG render, and Charlatan content) were combined and finessed heavily in comp. And in addition to all this, the environment also had to be fully reconstructed to work across both takes seamlessly and have Yelena interact with the CG set. We hope that when people watch this shot, they don’t even realize it is a VFX shot!

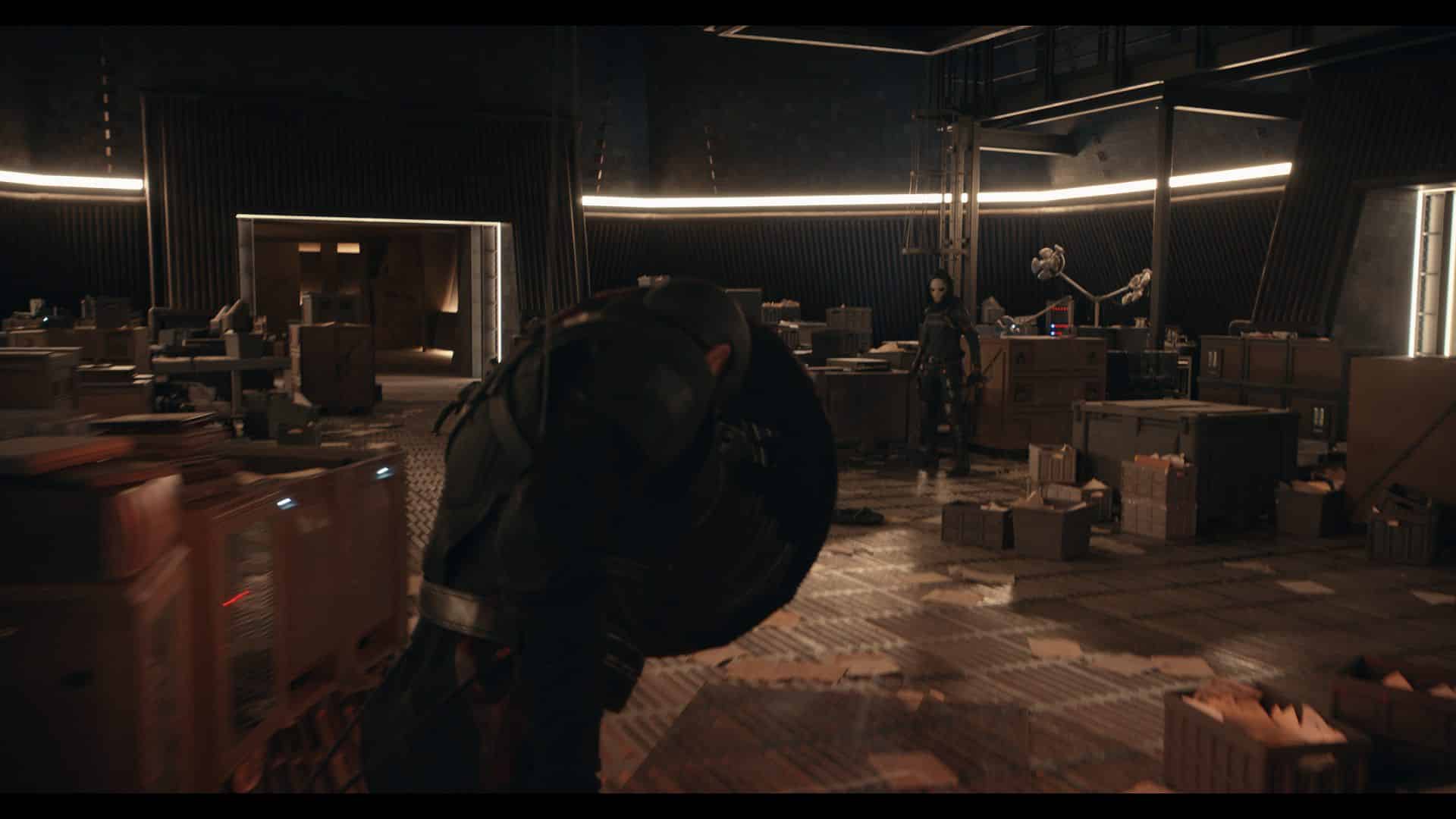

DP: Let’s talk Ghost. Her phasing effect must’ve gone through eleventy iterations. What was the final approach, and how did you balance the ‘techy’ visual logic with audience readability?

Ryan Wilk: In this iteration of Ghost, she has more control of her powers than in previous films, so her phasing was meant to be more intentional. For her motion, we tried to utilize her plate performance as much as possible, but played with the timing and spacing to create the ‘leaves’ of Ghost. We created the ‘leaves’ in animation, and then rendered them with varying shutter angles to provide comp with options from streaking effect with long shutters to sharp non-motion blur renders .

Our comp team then did the final sweetening, using chromatic aberration and varying levels of defocus and opacity to create the final look. It was quite a creative challenge, because we were not just adding the Ghost effect to each shot arbitrarily, we were experimenting and using the Ghost effect to help enhance the action of the stunts. Each shot with Ghost phasing was uniquely crafted from Anim to Lighting to Comp to get the necessary look for buy off.

DP: When the incinerator kicks in, things explode fast. What went into building the fire, pressure, and structural damage—without turning it into a Michael Bay moment?

Ryan Wilk: I think it really comes down to iterations. For the flood in particular, it did take a few rounds to find the right speed and volume to maintain believability. It was imperative to use past movies with live action explosions as reference to help determine the scale of the simulations. Once we were good with the fundamental simulation of the fire flood then we ran the secondary additional sims to drive elements like smoke, embers, boxes, papers, small debris to further help with the realism.

DP: Were there any custom in-house tools or pipeline tweaks developed specifically for Thunderbolts*—whether it was for sim setups, render optimization, or automation?

Ryan Wilk: Nothing in particular, other than maybe stretching the abilities of our face-swapping software, Charlatan, into new areas. A happy accident to discover that Charlatan can be used more like a glorified morphing tool to stitch plate characters with digi-doubles and vice versa.

DP: One thing about this vault brawl—it’s messy in a good way. Did you help shape the stunt choreography visually, or were you purely there to augment the physical fight?

Ryan Wilk: Most of the choreography is faithful to the original stuntvis, but we do like to think we contributed to it in small ways throughout the sequence. In one shot, for example, there was a bit of a pause in the stunt moves while Ghost and Taskmaster were fighting. The filmmakers wanted Ghost to be phasing, but because Taskmaster wasn’t actively attacking at that moment, the phasing felt unjustified.

So we replaced Taskmaster’s arm with a CG version, so that her sword swipes for Ghosts’s head. This allowed us to use the phasing as a dodge, and another ‘close call’ moment. There were little moments like this throughout, and the filmmakers were always open to our pitches to help improve and tighten the action of the fights.

DP: You retimed and repositioned Taskmaster’s arm mid-punch to sell weight. That’s oddly poetic. How much of the fight was rhythm-adjusted in post to maintain impact?

Ryan Wilk: We did things like this throughout the sequence, some very minor, some requiring a bit more surgery. And this is not to take away anything from the stunt work, it was very good. But adding just a little extra snappiness with the help of VFX makes everything feel just that much more intense.

DP: The camera move during Yelena’s throw is a standout—no fast cuts, no motion blur cheats. Was that shot the hardest to comp—or the most fun?

Ryan Wilk: Both!

DP: There’s a subtle photorealism to your digi-doubles in – they don’t scream “CG.” How do you approach the uncanny valley now? More shaders, better rigs, better lighting—or all of the above?

Ryan Wilk: All of the above. We are always trying to improve our digis, but for years now, if you were to take a look at our digital double t-pose turntables, you would agree they are highly photoreal. It is always fun when you show a side-by-side to someone and they can’t tell which is the reference and which is CG. But I think the challenge in sequences like this really comes down to the animation and motion. The human eye is just so keen when it sees things move unnaturally. So, superhero movies have always had this particular challenge…you have humans doing non-human things, and making that appear real to the human eye/brain is always tricky.

In Thunderbolts*, while there were a few moments where we were defying physics a bit, most of it was very grounded. The viewer could buy that something like this could be done by a very athletic human. And I think that contributed to us being able to get things to really sit in nicely.

DP: When you’re designing FX like Ghost’s phasing, do you think in emotional beats—like “this one should feel desperate” or “this flicker should feel like anger”?

Ryan Wilk: I don’t know if it got that nuanced, but it certainly was fun coming up with ways for her phasing to help the action. Let’s add a narrow miss here, Let’s have her pop up behind someone at just the right moment there for the ultimate sucker-punch, etc.

DP: What’s your current favorite “small-but-crucial” tool in your pipeline—something you think every VFX team should use, but maybe overlook?

Ryan Wilk: Well you were lucky enough to get the VFX producer for this interview instead of a supervisor, so am I allowed to answer with an excel formula? I’ll go with “Index match”.

DP: What’s the one thing you’d tell a VFX team starting their first Marvel-scale show?

Ryan Wilk: Be prepared for changes, show your work often, and be honest if you are in the weeds.

DP: Everyone’s talking about neural rendering lately. Did Gaussian Splatting, NeRFs or similar volumetric techniques sneak into Thunderbolts*—or are we still in “experimental, not production” territory?

Ryan Wilk: We’re actively investigating the Gaussian Splatting that Chaos introduced with VRay 7 for some relighting techniques and better lighting all around within our workflow. But for Thunderbolts* we stuck with the tried and true HDRs, using projections on combinations of LiDAR and layout geometry for our lighting.

DP: The vault is one of the most grounded VFX sequences Marvel’s done in years. What’s the shot in there that quietly makes you smile every time?

Ryan Wilk: There will always be one shot that makes me smile, and that is a seemingly simple shot where the vault doors all slam closed as the camera whip pans around the room. The doors in this shot are CG, and despite being one of the first shots turned over, it took ages for us to get this right. We had wedges of differing door drop speeds (simulated and key framed), different mechanisms for how the door panels move against each other. Numerous iterations on lookdev to get the door texture and lighting just right. Sometimes the most seemingly easy visual effects task can become a struggle. But we all get a good laugh out of it now.

DP: What’s next for you and Digital Domain—if it’s not NDA’d into a black hole?

Ryan Wilk: Not allowed to say quite yet, but Digital Domain has quite a few exciting projects going for the rest of 2025.