Table of Contents Show

Why ACES? The question is of course completely justified. Why should I switch my own workflow to ACES? Probably the best and most important reason is to bring yourself up to date before you are overtaken by it, because one thing is now clear: ACES is here to stay and has established itself as the new standard. But there are also very practical reasons in favour of ACES. Because ACES is “Scene Referred” – earlier workflows were already like this, but ACES does this for the first time in an almost open standard. With old “Display Referred” workflows, your own display was the measure of all things.

In principle, you only worked for one output format, namely that of your control monitor. in contrast, “Scene Referred” means that with the help of colour management, the settings that apply to the respective scene are equally valid in all different output formats and on a wide variety of playback devices. Everyone sees the same image. This is ensured by a shared library of LUTs and CTLs. And especially for users who finish or comp footage from several camera types, it will be an enormous relief to know that all the material is in the same, lossless colour space. But also for artists who have different deliverables, from web content to HDR masters, ACES is the best and, with a view to future developments, the most sustainable architecture on which to base their workflow.

A short refresher course

This article will focus on the practical set-up of an ACES workflow without Pipeline TD. We will clearly focus on the post-production aspect. Before we go into medias res, we will refresh the basics a little.

First of all, let’s clarify the most important question: What is ACES? Contrary to what many people initially assume, ACES is not a colour space, but a collection of conversions, standards and yes, colour spaces. Incidentally, ACES stands for “Academy Colour Encoding System”. Within ACES, however, there are also colour spaces that contain the name “ACES”, such as ACEScg or ACES 2065-1. More on this later. You can already see that one of the hardest parts of ACES to learn are the abbreviations. That’s why we’re going to go straight into the two most important ones: IDT stands for “Input Device Transform” and ODT stands for “Output Device Transform”. The IDT is responsible for converting the footage from the camera’s colour space to the working colour space. There are two groups of working spaces, the AP0 and AP1 primaries. The AP0 primaries, also known as ACES 2065-1, are defined as a colour space so wide and open that all light perceptible to the human eye is covered, and then some. This means that not only the signal from every camera currently on the market fits into this colour space, but also that of all future cameras.

ACES abbreviations

- ACES – Academy Colour Encoding System

- AP – ACES Primary

- IDT – Input Device Transform

- RRT – Reference Rendering Transform

- ODT – Output Device Transform

- OCN – Original Camera Negative

- OCIO – OpenColor Input/Output

- LUT – Lookup Table

- LMT – Look Modifying Transform

- CTL – Colour Transformation Language

The AP1 primaries, consisting of ACEScg, ACEScc and ACEScct, are not quite as extensive as the AP0 primaries, but still larger than all the classic spaces. ACEScg, as the name suggests, is primarily intended for CGI data and therefore relies on a linear transformation of the brightness information.

ACEScc relies on a logarithmic transformation, emulating the behaviour of classic grading tools. Last but not least, ACEScct is a variant of ACEScc, which emulates the behaviour in the lower ranges, i.e. the “Toe”, for which the t stands, somewhat differently. So much for the IDTs.

The ODT in turn converts the processed image into the colour space required by the respective playback device, i.e. monitor, projector, tablet, etc., for playback. Strictly speaking, an RRT (Reference Rendering Transform) is also responsible for this alongside the ODT, but this is usually applied under the bonnet by the software without the user intervening here. For the sake of simplicity, we will only talk about ODTs in the following. For playback in SDR, for example, this would be Rec.709, for the display of web content on a classic computer monitor sRGB and for the display of fancy HDR on a state of the art monitor, this would be P3-D65 ST.2084(PQ), whereby the possible NITS of the monitor must also be specified for HDR.

We will encounter these three terms, IDT, Working Colour Space and ODT, in almost all software when we start to set our pipeline to ACES. However, you shouldn’t let this put you off too much. Anyone who has already used active or passive colour management in software will also have had to deal with input and output LUTs and a working colour space. The terminology may be different, but many processes and principles are very similar. But before we leave the theoretical part behind us, let’s talk about the different ACES versions. ACES is an active standard that will continue to grow and, as described above, should also support future cameras and output devices. This is why new versions of ACES are released at regular intervals – ACES 1.3 is currently the latest version. It should be noted that these different standards are backwards compatible.

No or only minimal changes are made to the actual colour spaces, rather new ones are added. However, the focus of these new ACES versions is on the IDTs and ODTs. This is only logical, as the ACES colour spaces are defined so openly in order to support future sources and playback options. The IDTs and ODTs updated and added in the version updates are the key to this.

Ergo: If a software only supports ACES 1.1, for example, this is no obstacle at all to continuing to use the resulting files in a software that uses ACES 1.3. What can happen, however: If a software only supports ACES 1.1, for example, but you receive footage from the very latest Sony or Blackmagic camera, the corresponding IDT may not yet be included. You should definitely take this into account when setting up your workflow.

On to practice

In this workshop, we will be focussing on some widely used VFX tools, namely DaVinci Resolve, Nuke, Flame and After Effects. If you are missing one or two CG renderers here, the focus will clearly be on applications that have to deal with different footage sources. For a CG renderer like Arnold, it is relatively easy to set the output to ACEScg; if necessary, supplied textures would have to be converted to ACES. This article also ignores pure editing tools such as Premiere or Avid, so the focus is clearly on finishing and compositing.

We will consider Resolve and Flame as ingest, grading and finishing tools and Nuke and After Effects as comp tools to and from which ACES roundtripping is possible. But this should also be mentioned here: The principles are similar everywhere and as ACES is an open standard, much more software will support ACES than this article can cover.

And one more thing: This article is not a one-to-one instruction on what an ACES workflow should look like. Rather, it is intended to provide a safe introduction to the most common applications on the market – how you use these different apps in ACES together, whether Flame or After Effects, for example, appear in your equation or not, is not at all important.

Resolve

The top dog among grading tools is well prepared for ACES, but Resolve loves its own “DaVinci YRGB” colour science. We now have two options as to how we want to set up our workflow: Do we rely on Resolve’s colour management or do we prefer to do it ourselves on a scene-by-scene basis.

If Resolve is only used for drawing plates and grading, but the finishing is done in a different system, then it may make sense to leave the colour management to DaVinci. However, if we also want to finish in DaVinci, a manual workflow makes sense – working with titles and graphics in particular is easier if the colour management doesn’t interfere unintentionally.

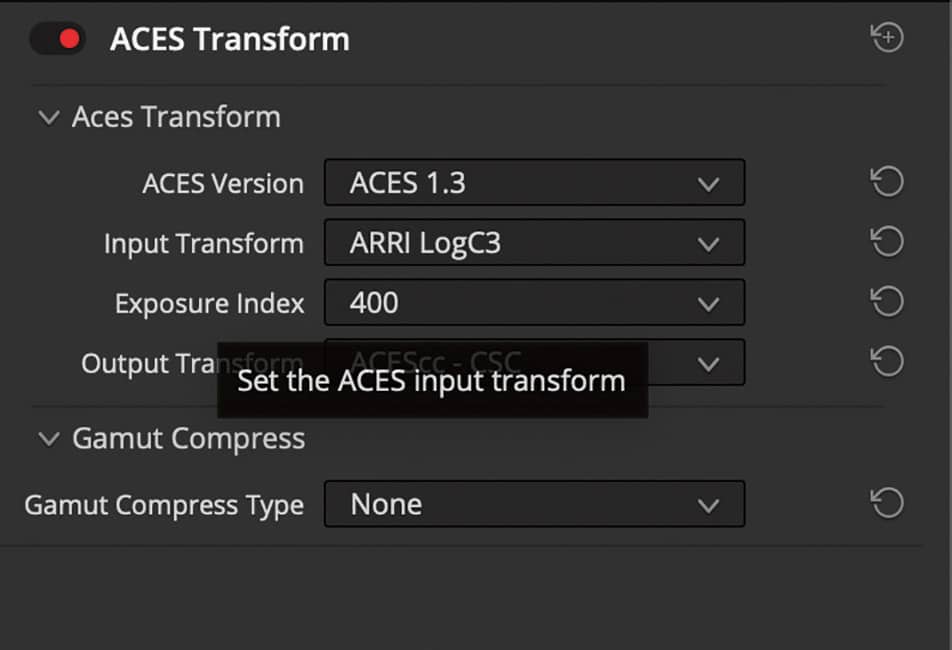

Colour management through Resolve

In the preferences, which we can access via the cogwheel at the bottom right, please select the “Colour Management” area in our current project and select ACEScc. Alternatively, we can also use ACEScct. Technically, it makes no difference which colour science we choose here. Next, we select our ACES version; ACES 1.3 is the current version for Resolve 18. We can now select a predefined IDT. This makes sense if you only have footage from one and the same source in the project, as it saves you having to tag it manually when importing later. However, this also bypasses the automatic detection, where Resolve tags the colour space correctly based on the metadata. Exceptions to this are RAW files, where Resolve always takes over the input mapping.

However, this does not explicitly mean setting the debayer, exposure and colour temperature settings. To start with, we will not select an Input Transform and move on to the ODT. Unfortunately, Resolve is a little awkward here, as it uses the same Output Device Transform for the display on the monitor and for the export. For us, this means that we first select the ODT that we need for correct display on our grading monitor. Before exporting, however, we must then return here and select the correct ODT for the export. Depending on what our individual setup looks like, we now select sRGB, Rec.709 or another suitable ODT.

That’s it for now with the preferences. But if we haven’t selected any IDTs in the preferences, how can we tag our clips? The simplest way is to right-click on the thumbnail in the colour tab. Here we can then select the IDT suitable for our footage under “ACES Input Transform”. The usual suspects such as ARRI Alexa, Sony Venice, Black Magic etc. are available here.

User Managed Colour

Just because we take colour management into our own hands doesn’t mean we have to do without ACES. We can leave the preferences alone for now, the preset “DaVinci YRGB” and an output transform that matches our setup are perfectly fine here. We simply move the step that is usually performed by the colour management, namely the conversion from and to ACES, to the node level. In the “Colour” tab, we also find the ACES Transform Node among the OFX plug-ins. This offers us the same options as colour management, only at a clip/timeline level and not for our entire project

entire project.

This means that we can also select our ACES version, our IDT and our ODT here. Depending on the footage, we now select the corresponding input transform and select ACES as the output. However, our image will still be displayed incorrectly in the viewer, because although we have linearised our image, our display is not linear. Unfortunately, unlike Flame and Nuke, Resolve does not have a dedicated Viewer Transform. However, this is not a major problem. We can take the timeline level of our colour tab (set the drop-down menu from “Clips” to “Timeline” at the top right) and select an ACES Transform again. This time we select “ACES” as the input transform and the colour space of our monitor as the output transform, i.e. Rec.709, sRGB or whatever matches the device on the desk.

This transform now lies like an adjustment layer on our entire Resolve timeline and thus ensures a correct display on our monitor – it is only important that this transform is switched off again before the export, otherwise it will be included in the export and we will not export a correct ACES.

If you find it too tedious to go through each clip individually and manually distribute Ace’s colour transforms, here’s another tip.

Resolve has the wonderful option of combining various clips into groups. If you have combined several clips from the same camera into a group, you can define not just one but two transforms for the group – a pre-grade and a post-grade. This means, for example, that the pre-grade group can contain the ACES colour transform node with the transform from camera colour space to ACES and post-grade can then contain the conversion from ACES to the output format. In this way, a large part of the work can be automated even without colour management. However, it gives us the freedom to leave ACES again at a certain point if this is necessary for our workflow.

Exporting files from Resolve

Whether in the managed or manual workflow – Resolve does not recognise a viewer transform and so either our output transform must be set to “No Output Transform” in the preferences or our ACES transform must be deactivated at the timeline level. Once this is done, we can switch to the Deliver tab and prepare our export. OPEN EXR in RGB Half PIZ compressed is the most suitable export format here. Half stands for 16 bit, which is more than sufficient for our footage files and PIZ as lossless compression is read by Nuke and After Effects without any problems. In any case, we should render in Source Resolution. Under Advanced Settings, we select “ACES AP0” as the colour space tag and click the checkboxes for “Disable sizing and blanking output” and “Force Debayer to

highest quality”.

Who still needs LUTs?

We’ve been working with colour space conversions for quite a while now and haven’t needed a single LUT. Well, that’s not quite true, because the IDTs and ODTs that we use all the time are, strictly speaking, also LUTs.

But, and this is the important distinction, this time we don’t want to make a technical conversion to a different colour space, but rather make the creative look that was generated in Resolve visible and usable in other software. This is intended for the case that we either do the grading in Resolve ourselves or we want to have LUTs delivered by a colourist for our ACES pipeline. Please note the following: All corrections that use masks, gradients, blurs or similar limitations, for example, will be ignored by our LUTs. However, if only the colour value of a pixel is actually changed, these changes can be saved in a LUT and transferred to another tool.

For example, to see directly in Nuke what the comp looks like with a rough grade applied, this is a great way to avoid unnecessary roundtripping. To export a LUT from Resolve, we activate the nodes in the node tree of the colour tab that are to be part of the LUT, right-click on the thumbnail of our clip and select “Generate 3D LUT(65 Point Cube)”. Select the target folder and a name – done.

And what about graphics?

When we talk about graphics, we need to make a fundamental distinction. Are the graphics part of a scene, for example a screen insert that is tracked into a smartphone, or are we talking about titles, belly bands and other graphics that take place outside the scene, so to speak?

Let’s start with the first scenario: We receive a screen insert in sRGB, for example as a tiff file. We can provide this with an IDT from sRGB to ACES and then work with it as normal within the scene in which it is to be used. This is not a problem because we have a common denominator for the black and white values within the scene and can then match them with each other. So we also work “Scene Referred” here.

Things get more complicated when we have graphics that are not related to the scene. Let’s take the previously mentioned belly band, for example. Its white value has no relation to the scene on which it sits, but it should be white for the end user. However, ACES is not an output format and the biggest problem when dealing with graphics is the incredibly wide range of brightness values that one display can have in comparison to another. A white font in Rec.709 has a brightness of 100 nits. With an HDR display, however, we quickly reach 1000 nits – the 100 nits of Rec.709 are a pale grey. As you can guess, this is very much about the display. So we are working with “Display Referred”, something,

aCES is simply not designed for.

Strengths and weaknesses

And this brings us closer to the real reason why the ACES workflow managed by Resolve is not practical for mastering. If you select ACES colour management in the preferences, every timeline within the project is considered ACES. You do have the option of setting a Graphics White Level in the preferences, for example.

This defines the brightness of titles, colour areas and gradients generated in DaVinci, but in practice this function fails the moment you import external graphics. The bigger problem comes when mastering, when you always have to set this white level value via the preferences in order to create different output masters. It is simply very difficult to understand and prone to errors.

This is the strength of the manual workflow, where thanks to the ACES colour transforms, the transformations do not take place globally, but locally from scene to scene. Here you can finalise your grade on a master timeline and then move it to the colour space of the respective deliverable via the corresponding ODT. If you then place graphics and titles on the timeline afterwards, you can do this in the best possible quality for the respective output medium. And if you have to create several deliverables, you can copy the timeline, adapt the ODTs and place the graphics on it accordingly.

Roundtripping to Nuke

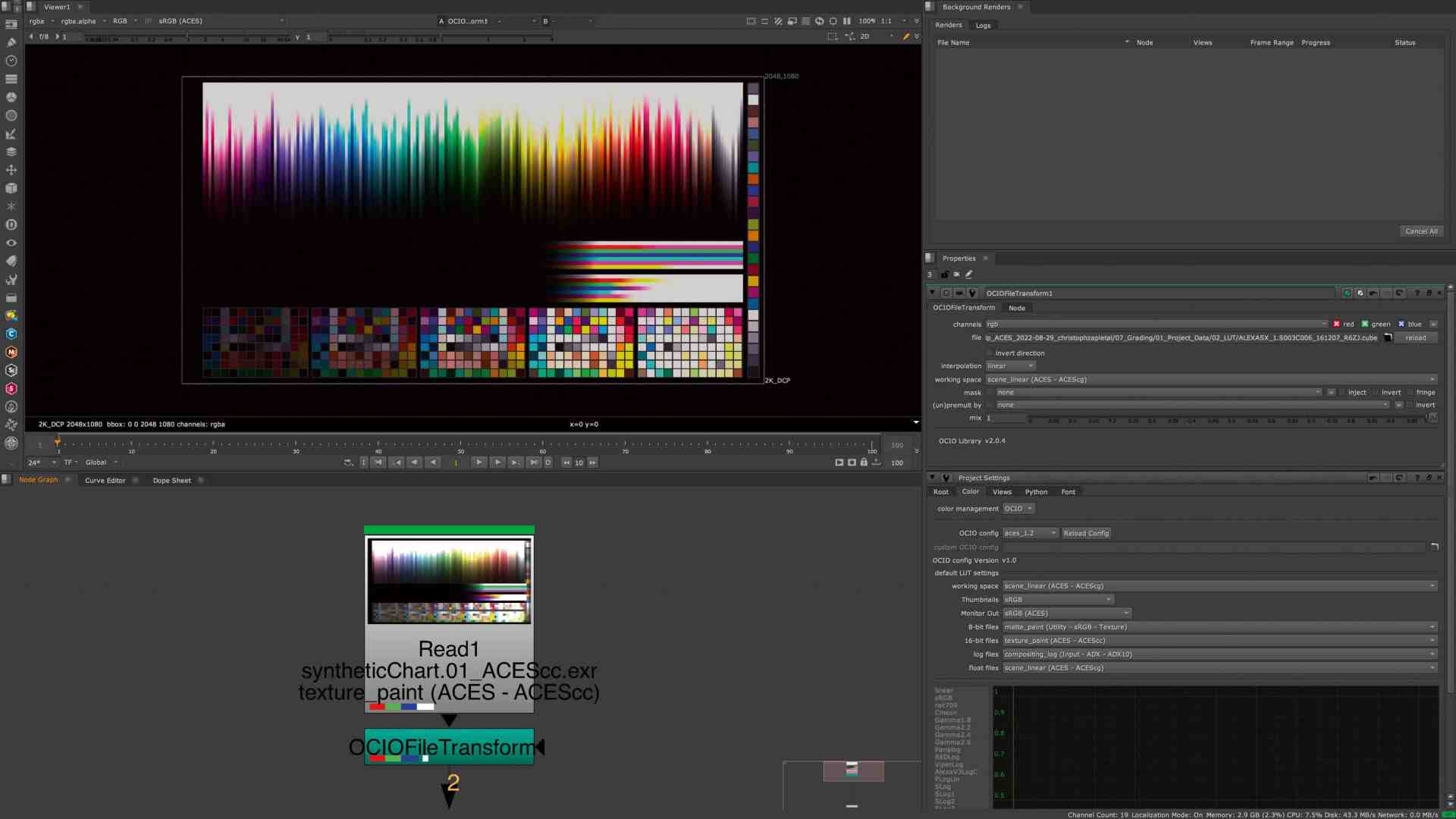

Colour management systems are like opinions – everyone has one and far too many keep them to themselves. So Resolve has “DaVinci YRGB” and Nuke has – very creatively – “Nuke”. This is the name of the in-house colour management system, which has basically ensured since Nuke’s earliest days that all scenes in Nuke are first linearised and then comped. However, Nuke only takes the gamma curve into account, the colour gamut is completely disregarded. Fortunately, since version 11, Nuke has been supplied with OpenColor IO (OCIO) profiles to which we can transfer the colour management. And in the current Nuke 13.2, these also support ACES version 1.2.

This means that we first go to the Scene Settings in Nuke (park the cursor in the Node Graph and press “S”) and switch to the Colour tab. Here we select OCIO instead of Nuke. Directly below this we can then select the OCIO Config File and take ACES 1.2. Below this we see the suggested behaviour, which types of files should be provided with which IDT by default. We can of course adapt these to our workflow, but the defaults here will work perfectly for the start. There is one last thing we need to do: Unlike Resolve, Nuke has its own viewer transforms for ACES, and so we need to set our viewer to the correct colour space. For a standard PC or Mac monitor this would be sRGB(ACES).

Exports

Now we can load our exports from Resolve into Nuke via a read node. If we still have the previously exported LUT, we can load it via the “OCIO File Transform” node. It is important that we select the same colour space here as in Resolve, i.e. ACEScc. The output should now be exactly the same as in Resolve (please remember to switch on the ODT that was previously deactivated for the export). Of course, we can also create the OCIO File Transform Node as a viewer input to make it usable more quickly at any point in our comp. Otherwise, the work at this point is not much different than in the classic Nuke workflow. Only when exporting from Nuke do we now have other options in the Write Node that OCIO makes available to us.

Ultimately, an ODT is also applied in the write node, and so we can set our colour space for an EXR sequence to ACEScg for roundtripping back to Resolve or, if we want to be completely correct, to ACES 2065-1. In principle, however, there is nothing to stop you from rendering a file in Rec.709 or sRGB directly from Nuke for matching purposes, as long as you select the correct colour space in the write node.

ACES in After Effects

We have already talked extensively about graphics and “Scene Referred” vs “Display Referred”. So it should come as no surprise that we are talking about pure “Scene Referred” work in After Effects, i.e. working on the plate. Unfortunately, After Effects is inherently ill-equipped for ACES (still! See interview from page 16).

On the one hand, After Effects loves to do a lot of colour management itself. Secondly, it does not even come with the required OCIO plug-in and the corresponding config files as standard. However, we can download and install these at is.gd/ocio_in_ae and is.gd/ocio_config.

Now it’s time to get rid of the colour management in After Effects. In the Project Settings under the Colour tab, we set the Bit Depth to 32 and the Working Space to “None”. Now we can get started and import our exports from Resolve. However, After Effects still wants to interfere, which is why we right-click on our footage under “Interpret Footage” and tick “Preserve RGB (disable colour management for this item)”.

And now?

The image will now look quite dark, as we are once again looking at a linear image without a viewer transform on a non-linear display. So we need a viewer transform, which After Effects doesn’t have by default. So we use another trick that we have already used in the manual workflow in Resolve. There we applied an ODT to the timeline level. We are now doing something similar in After Effects – with an adjustment layer. So we create an adjustment layer above our footage and name it “Viewer Transform”.

Now we select “Guide Layer” by right-clicking – this way it will be ignored later during rendering and we won’t accidentally include our Viewer Transform in the export. Then we look for our newly installed OpenColorIO plug-in. We select ACES 1.2 as the configuration and the input transform should correspond to our export from Resolve, i.e. ACES 2065-1.

We use Rec.709 as the output transform, as After Effects always uses Rec.709 as the default setting. By the way: We can also apply our LUT from Resolve in exactly the same way, i.e. using the Adjustment Layer and OpenColor IO plug-in, if we want to.

If we now want to use graphics – which is quite common with After Effects – our OpenColor IO plug-in is used – this time not as an adjustment layer but directly on the file. We set the input to Utility – sRGB – Texture and the output to ACES 2065-1. From here we can continue comping as normal in After Effects.

To render, we now put our scene on the Render Queue. In the Output Module Options we select an OpenEXR Sequence and the already familiar PIZ compression in the Format Options. In Colour Management, we tick the “Preserve RGB” box again – otherwise After Effects will want to mess with our image again.

Editor’s note: While this article was already on its way to the printers, After Effects was updated. ACES workflows are now actively and natively supported in the beta version, but we do not yet know when this feature will be available at the time of going to press.

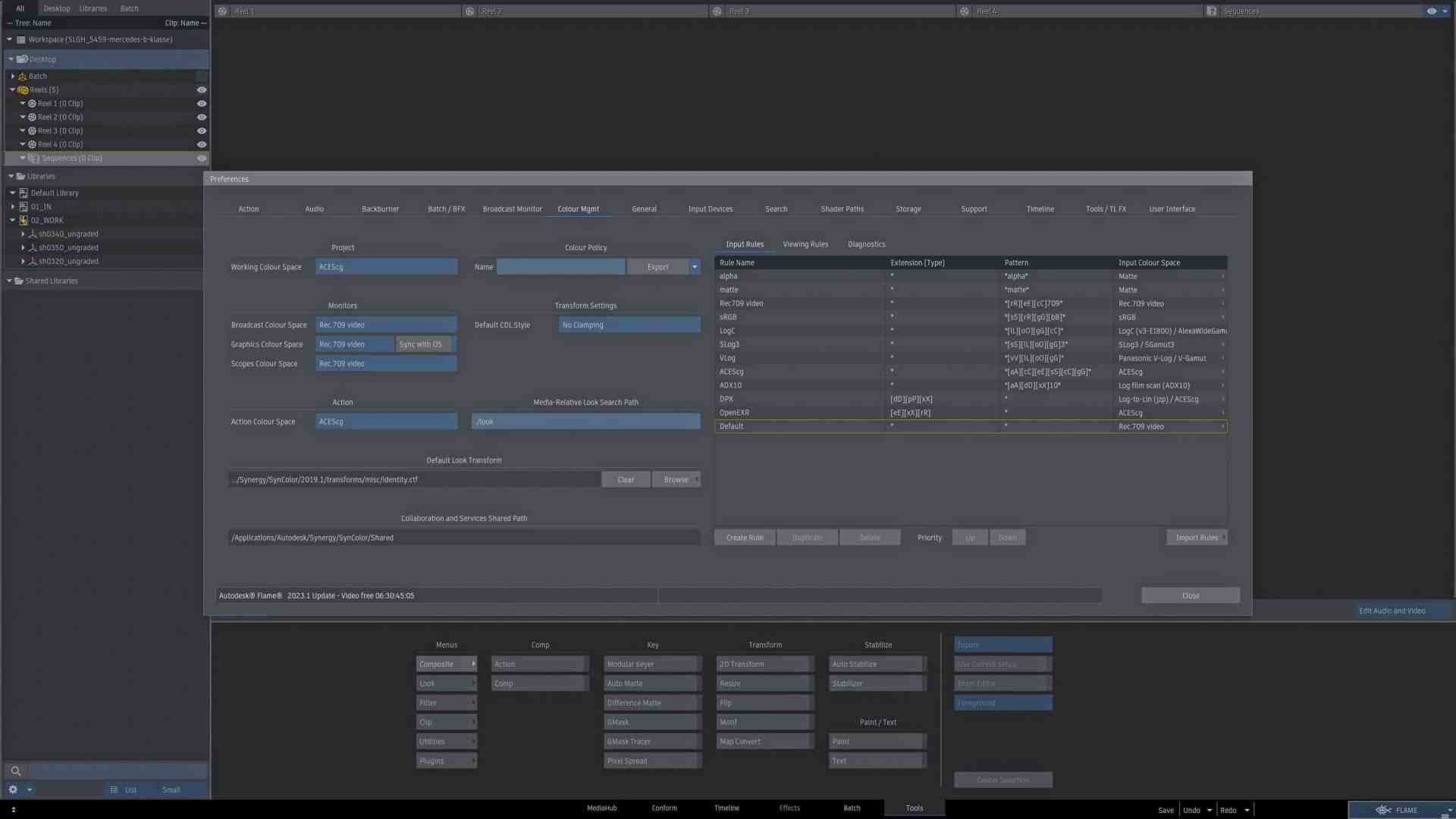

Tagging and input rules – ACES in Flame

While Resolve’s colour management aims to make things as easy as possible for the artist by carrying out as many transformations as possible under the bonnet, Flame has a diametrically opposed approach.

Flame’s colour management is designed to be adapted, modified and changed at any point. This makes it a little confusing and intimidating at first, but also gives us a lot of freedom and options that are not available in Resolve. In the conform and grading phase, this is not yet so interesting for us. However, this changes abruptly when it comes to finishing and exporting.

Let’s start with the very basics: We create our project. Under “Colour Policy”, “ACES 1.1” is available as a selection option in Flame 2023. Together with our other default settings such as frame rate and resolution, we select these. All these settings, including colour management, are regarded by Flame as a starting default rather than being set in stone.

This means that Flame allows us to create a Rec.709 composite or an sRGB timeline even in an ACES project. These project settings only ensure that ACES is selected as the standard for new nodes and timelines and that some import and viewing rules are created that are helpful for the ACES workflow, which we will discuss briefly later.

When importing clips in the Media Hub, Flame offers us two options that we should discuss briefly: Firstly, we can tag clips, and secondly, we can convert them. Tagging means that the actual media is not converted, but the clip is given a marker within Flame to indicate which colour space the clip is in. When converting, the clip is converted from its native colour space to a working colour space. Both working methods have their advantages, but precisely because Flame offers the option of colour space conversion in so many places, we should opt for tagging at least to begin with – even if only to gain a better understanding and practice in dealing with Flame’s colour management.

In addition to the pull-down menu with the previously mentioned options, there is another pull-down menu with the colour space that is to be tagged (or converted if necessary). The default setting here is “From File or Rules”, which means that Flame will attempt to recognise the colour space either using metadata (from File) or using the previously mentioned “Input Rules”. If we now briefly leave the Media Hub and go to the Preferences, under the Colour Management tab, we can see these rules – at least the ones that Autodesk has added to the ACES Colour Policy. In short, tokens can be used to create automations so that, for example, files that have a certain name, a certain extension or are located within a certain folder are also assigned a certain colour space.

This is extremely powerful when setting up your own workflow, but it is also definitely an advanced feature. To start with, we will tag our clips manually. It’s relatively quick and it’s simply more transparent what happens where. If we now open the pulldown, we can select the colour space of the material and drag it into our library.

The tagged colour space is now literally attached to the clip; we will now be able to see it on every thumbnail, in every info box. And just to avoid any misunderstandings: The clip is not yet in the ACES colour space.

There are various places in Flame where a clip can be converted and Flame is also very lenient where clips of different colours can coexist. A batch setup can therefore contain several clips of different colour spaces and a timeline in which a RAW clip lives between an ACES clip and an sRGB clip is also possible in principle – albeit with restrictions.

Timeline

Let’s start with the timeline: How does Flame manage to display these three different colour spaces next to each other correctly? Well, Flame has one thing that we have already sorely missed in Resolve: The View Transform: this is basically an ODT for our used playback display. However, it is not fixed, so it doesn’t just convert from ACEScct to Rec.709, for example. It is also not applied to the export by default – unlike in Resolve – but is switched “live” to the viewer. The View Transform refers to a second set of rules – the Viewer Rules.

we can also take a look at these in Preferences under the Colour Management tab. They are used to define how which material is converted and on which type of display what exactly is shown and how. This is why tagging is so important in our workflow – this is how Flame receives the information about what the material looks like and how it needs to be converted. Incidentally, we don’t need to create our own viewing rules – the set supplied by Autodesk should be more than sufficient for most of us.

Batch

In Batch we can process these images from different colour spaces together, but the colour science will definitely be wrong – we have to bring the images into a common colour space. Like almost everything in Batch, we do this via a node, namely the “Colour Management” node. Here, in addition to a few other “legacy” options, we can carry out two transforms that will be important for us: The View Transform and the Input Transform. You might think that Input Transform is Flame Lingo for IDT and View Transform for ODT, but that’s not quite true.

To create an IDT, we always use an Input Transform and select “From Source” under “Tagged Colour Space”, as we have already tagged our source correctly. We then select our ACES colour space under “Working Space”. As with Resolve, this can be ACEScc or ACEScct, but ACEScg is also very helpful in a comp-heavy app like Flame. However, this process can also be reversed using the “Invert” button and can therefore also be used to create an ODT.

The View Transform, on the other hand, is purely intended for the ODT and works according to the WYSIWYG principle. Flame looks at the active viewing rules and takes these as the ODT to be applied. Very practical if you want to export a clip or a timeline quickly – but rather unsuitable for converting in batch. So we stick with the Input Transform and convert the clips to the ACES flavour of our choice. From now on, we can combine all clips diligently in Action – Action behaves here as in any other colour policy: it either adopts the colour space of the inserted background or jumps back to a default that was defined in the preferences. For Flame’s ACES colour policy, this is ACEScg. This is also important when generating things like lens flares or particles in Action.

The IDTs and ODTs just described in the form of View Transform and Input Transform can be found in half a dozen places in Flame. We can set it on the media level, we can set it on the incoming clip in batch, we can do it in a separate node as just described, we can mess it up within the render node, we can apply colour management on the timeline or during export. This all makes perfect sense, but it’s far too much to start with. We limit ourselves to three levels: Within the flowgraph in batch (which we have already discussed), on the timeline level and when exporting. Now let’s move on to the timeline level.

We have already been able to admire how Flame can wonderfully display three different colour spaces in succession, but we have not yet discussed the associated limitations: Blending between Slog3 and sRGB, for example, won’t work.

If the timeline is not at least 16 bit, we will have to deal with a lot of clipping. Certain effects, which can also be applied to the timeline, are calculated differently or sometimes incorrectly depending on the colour space – a defocus, for example, may only work with linear material.

So we have our correctly tagged material coming from different colour spaces. How do we get all this material into a common colour space? The solution is a timeline effect called “Colour Management”, which is structured in exactly the same way as the node of the same name in Batch – in fact, it is also the same operation and the same source code as in Batch, just applied in a different part of Flame. However, there are two effects with the same name, one in green and one in Flame’s typical grey. The green one takes effect before all resizes and other effects, and thus converts at the source level – above all definitely before the image effect, which is used when grading in Flame.

Gap FX

However, the colour management effect can also be used as a gap FX, i.e. as a kind of adjustment layer on the timeline. Wait a minute, wasn’t there something in our manual Resolve workflow with an ODT that we applied to the timeline level? Exactly! Here, for example, we can use the View Transform to bring an entire timeline of ACES clips into a colour space like Rec.709. Of course, this timeline must also be able to handle ACES, i.e. it must be at least 16-bit float, even if our deliverable is Rec.709, as in this example.

What is really exciting, however, is the fact that this effect is simply a layer on our timeline. A layer over which we can place other layers. With graphics and belly bands and titles… in the correct target colour space. And the View Transform really lends itself to this, as it allows us to make three settings: The tagged colour space, in this case the ACES colour space we are using. Then the View Transform, where we can specify the exact colour science behind the conversion. For example, “ACES 1.1 SDR video”.

And under Display, following the aforementioned WYSIWYG principle, Rec.709. We won’t see any visible difference on the timeline itself, but if we switch between the layer on which our ACES clips are located and the one with our colour management gap FX, we will see the colour space jump in the bottom left-hand corner of the display. And if you want to be extra sure, click on the “Active” button in the viewer and bypass the ODT on the display. The difference should then be clearly visible.

Finally, the export: We won’t go into every detail here because, as mentioned before, the basic structure of colour management is the same everywhere in Flame. If you only want to bring your timeline into the target colour space when exporting, select the somewhat old-fashioned “Use LUT” under Advanced Options. From here you can then assign the same ODT to the individual export as we have just done with the timeline. In principle, however, I would advise against this, because unlike a timeline effect or a node in the batch setup, the export settings are no longer attached to the clip. That’s why, especially for beginners, I would advise everyone to make the transformations where they can still be traced afterwards: in the batch and on the timeline.

Stumbling blocks

Fortunately, ACES is now widely supported. Boris FX has made many of its products compatible with OCIO in recent releases, which means that plug-ins such as Mocha Pro or Silhouette can also be used in an ACES workflow. However, not every manufacturer is that advanced and we have already noticed it a bit in this workshop – Adobe is unfortunately not really “ACES Ready” by default.

With After Effects, this is a minor annoyance, but it can be solved with a few downloaded config files and a few changed settings. Things are more difficult with the industry standard Photoshop. Photoshop is unfortunately the definition of “display-referred” software, and the concept of colour spaces, at least as we know them from the video world, is simply not known here. To make matters worse, not all Photoshop functions work in 32-bit. Daniel Brylka has described a hack on his very good blog www.toodee.de on how to use the proofs in Photoshop to work logarithmically on ACES looks, but it is anything but intuitive. There is definitely some catching up to do here.

If you’re serious about ACES, you should definitely create a small test project and put your own pipeline through its paces before sending the first customer job through. If you don’t want to download test footage of Kamers from ten different manufacturer sites, we recommend at least this page: is.gd/aces_central_references.

Here you can find wonderful test images in all possible colour spaces, which should definitely reveal any errors in the pipeline. And it offers us the wonderful opportunity to experience what ACES promises – that our images really do look the same in any software.

Conclusion

Using ACES outside of a large pipeline is now absolutely feasible – even if the support in the various tools varies, good roundtripping is feasible. ACES is here to stay and there are good reasons to use ACES.

Making your own work future-proof, no longer bending colour science, but using it for better images and using the maximum possible colour space are all good reasons to take the step towards ACES.

Finally, I would like to say thank you, because this article would not have been possible without the great work of Finn Jaeger, Daniel Brylka, Chris Kasten, Grant Kay, Lars Wemmje and Randy

McEntee, who have already shared their knowledge with the community. I have put their respective articles or videos in the link box and would warmly recommend them to anyone interested.