Chris Wojtan and his group are researchers at ISTA – the Institute of Science and Technology Austria

(ista.ac.at), and they deploy and develop techniques from physics, geometry, and computer science to create efficient simulations and detailed computer animations. Chris has been at ISTA since 2011, after getting a Ph.D. from the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. And you can see the publications and the rest of the group – as well as current and upcoming projects at bit.ly/ista_wojtan

DP: After all we have seen in cinemas over the years, you would think that water simulation would have been perfected by now?

Chris Wojtan: Humans have known about water for tens of thousands of years, and they only started really understanding how it worked in the 1800s, when physicists Navier and Stokes wrote down their famous equations explaining how fluids flow. Although these equations are easy to write down, we haven’t been able to solve them in the past two hundred years. Engineers and physicists have been trying very hard! In the year 2000, the Clay Mathematics Institute made it one of the “Millennium Prize Problems” just to find out whether a solution to these equations is even proven to “exist”… that’s how far we are away from really understanding how fluid flows. Since “perfecting” water animation really boils down to perfectly recreating its motion in any scenario, a “perfect” animation means solving one of the most infamously difficult problems in the history of mathematics.

We are constantly working on this problem, and trying to improve upon the state of the art every day. This year’s work makes things better by combining two things that used to work great before but never worked well together: Specifically, we already know how to simulate shallow water, like flooding onto a beach and sloshing around; we also know how to simulate tiny waves rippling in deep water, creating beautiful interference patterns like the ones you see behind a boat or a duck swimming in a pond.

Up until now, it was surprisingly difficult to put both of these together in the same animation, like having a boat create a wake that splashes up onto the beach. We did this by unifying different solutions of the Navier-Stokes equations, to make sure they work well together in a way that physically makes sense.

DP: What are the relevant influences on wave formations?

Chris Wojtan: Water waves are extremely complicated, so we have to simplify the physics just to get a handle on the problem. The main forces that influence water waves are:

– Gravity – the entire column of water is constantly being shoved downward

– Surface Tension – the surface of the water wants to stay smooth, so any ripples get pulled hard upward or downward towards a flatter surface

– Fluid Pressure – fluid is extremely good at resisting compression. Any amount of pushing on it will cause water to spill out into other directions. A wave pushing downward causes fluid to flow around sideways.

– Viscosity – internal friction causes the wave to resist sloshing about too much.

One of the reasons that water waves are not so simple to explain is because they are “dispersive”. The speed that a wave travels depends on its wavelength. Huge kilometre-scale waves like tsunamis are driven strongly by gravity and travel really fast; millimetre-scale waves are driven strongly by surface tension forces and also travel extremely fast (blink and you will miss them); the centimetre-scale waves in between aren’t really pushed that hard and actually travel slowest. The result is that you have all sorts of waves of different scales all travelling at different speeds. It is a mess to understand, let alone writing code in a computer to perfectly recreate their behaviour. However, this behaviour is responsible for extraordinary beauty. Pay attention to the ripples you see in a pond, and you will see that all the ripples rip apart into different wavelengths, automatically sorting themselves out into longer or shorter waves in front or back.

DP: And jumping from 2D to 3D and back makes it easier?

Chris Wojtan: Yes! It is a pretty useful technique in maths and computing to try to take a complicated problem and make it as simple as possible before solving it. Some people call it a “change of variables” or use fancy words like “reduced degrees of freedom”. The basic idea is, if I somehow knew that a super complicated problem could be easily transformed into a simple one that I already know how to solve, then I definitely want to solve that simple one instead of the hard one. Transforming a 3D fluid problem into a 2D surface prob-

lem makes it simpler to solve in a computer, in the same way that solving 10×10=100 math problems is easier than solving 10×10×10=1000 math problems. The computer loves it when we do this, because then it can take a break and doesn’t have to work so hard.

DP: Why hasn’t this been done before?

Chris Wojtan: You are right that so many people have looked at this problem before. Fluid flow is so ubiquitous and important to so many people in different ways, but water surface ripples are somewhat of a niche problem in the big picture.

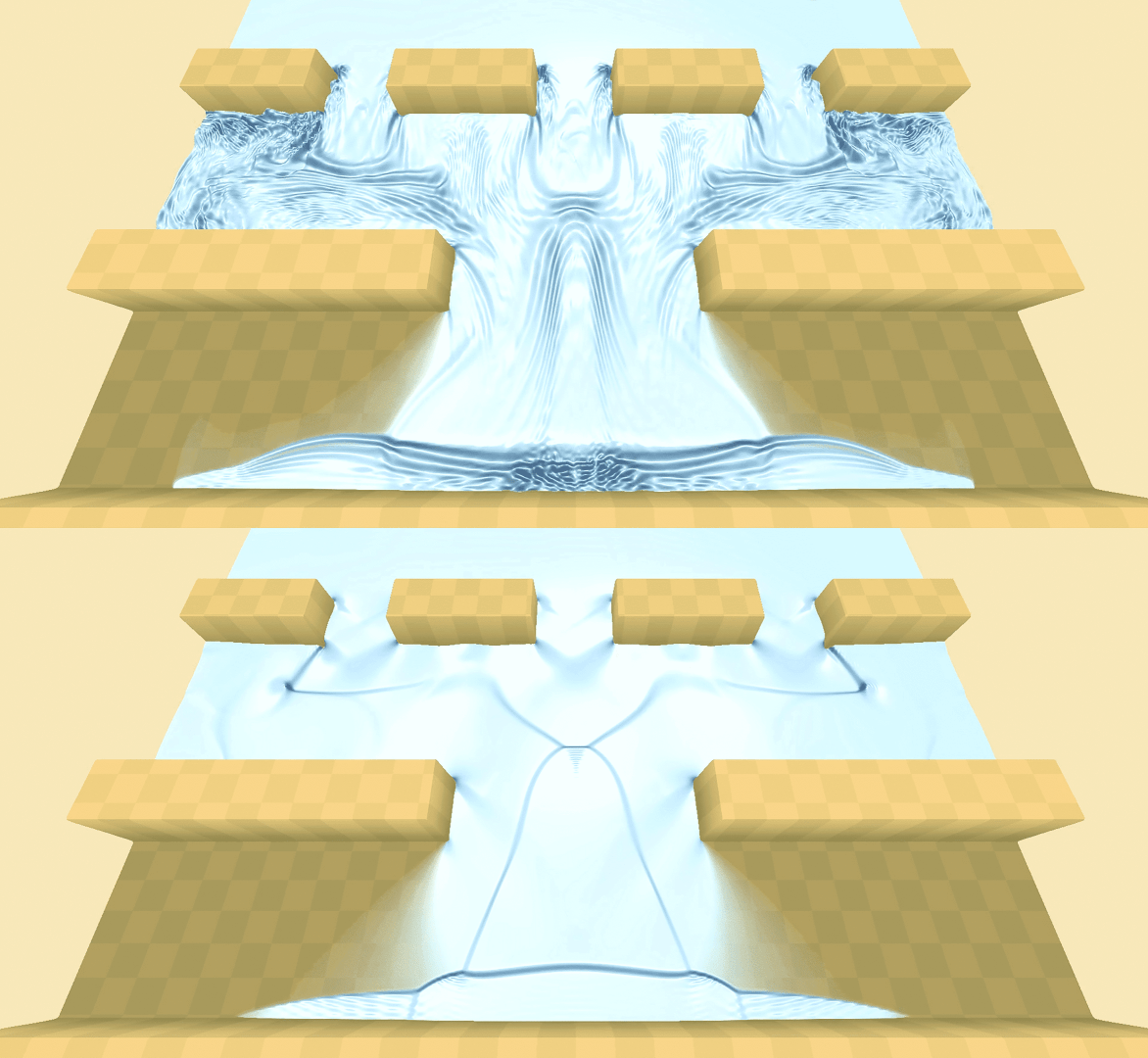

SWE simulation (centre) with enriched details.

Recent breakthroughs in computer hardware make it so that some algorithms suddenly become more useful than others. Although people knew about fluid equations for hundreds of years, we only had the computer power to simulate waves efficiently for the past few decades or so. The state-of-the-art computer methods for shallow water equations came even later, and super fancy exponential integrators for surface ripples came even later after that. Each of these ideas are somewhat different from each other and are honestly somewhat intimidating to people trying to understand them. I believe the main reason we haven’t seen this idea before is because it combines so many different ideas that are hard to keep straight in your head all at once, and each of the ideas are relatively new in the grand scheme of things.

On the other hand, it is somewhat surprising that we haven’t seen progress here earlier. Stefan Jeschke (first author)’s “Eureka” moment came from just playing around with the state-of-the-art tools and realising that they failed so obviously when combining them together. The shallow water simulators simply do not speak the same language as the ripple simulators, and they don’t work well if you try to combine them. Our idea was to force them to speak a common language, which required some trickery and lots of trial and error.

DP: So your new way of simulating waves by “splitting” the equations and recombining them works in all types of water?

Chris Wojtan: Definitely not! We had to put a lot of constraints on the problem in order to get an answer that is fast to compute. For example, we have to assume that water resists compression so much that it is essentially “impossible” to compress it. We also had to assume that waves could only go up and down, and not tumble over themselves or rip apart into droplets and bubbles. These are common ways for physicists and mathematicians to cheat around hard problems, and we did the best we could to use these ideas to make the problem as simple as possible to solve. So, the only reason that we can compute it so quickly is because we were able to simplify the maths, which prevents it from working in all possible water scenarios.

DP: With simulations in CGI, different materials and situations can be used with identical “simulation approaches” – how flexible is your new model and what are its limitations?

Chris Wojtan: Our research covers all sorts of interesting situations, with some methods more general and some more specific. This one is very specific and uses as many constraints as we could to make it fast to compute. This one only works for water waves and is not a general simulation approach. It can definitely be combined with other methods, though.

DP: Walk us through the steps, what happens to the “fluid particles”?

Chris Wojtan: In the real world, the fluid particles behave differently depending on the water depth. Far away from the beach in very deep water, the fluid particles simply bob around in gentle circles. Waves pass through them, but the water particles themselves just move lazily around in a circle – as their neighbour goes up, they get pulled up along with it; as the neighbour falls back down again, they get pulled down with it.

In shallow water, there isn’t as much room for the fluid particles to plunge up and down again. If they try to go downward, they either smack into the floor, or they smack into one of their neighbours who can’t move out of the way because the sea floor is in the way. These fluid particles can’t go in simple circles anymore, and instead they generally tend to move away from each other by sliding left and right.

It turns out that both of these ideas are going on everywhere in the water, but at very different scales. If you see a very short wave compared to the water depth (like a gentle ripple in a pond, or a ship wake in the deep ocean) then the fluid particles move in lazy circles. On the other hand, if you see a very long wave compared to the water depth (like a tsunami in the ocean, or a raindrop in a puddle) then they will slosh side-to-side. Both of these can work together at the same time. Long waves move side to side, while short ones bob up and down. We combine both of these ideas together to get a simple wave solver that combines some of the best-known ideas for simulating each wave type on its own.

DP: And with something so abstract, how do you test it?

Chris Wojtan: This is a really important question that we have to critically ask ourselves on every research project. The simplest thing to do is just try it out and see if it makes any sense. Beyond that, we try to see if the simulation acts the way we would expect it to in as many different scenarios that we can dream up. This is usually some mathematical concept that also makes sense in the real world. Some examples:

– Conservation of mass: Does the water disappear for no reason or is water created out of nowhere like some leaky faucet?

– Conservation of energy: Do the waves settle down naturally? Do the waves keep feeding back on themselves, getting stronger and scarier?

– Dispersion: Do waves travel at the right speed? Can we recreate the nice patterns we see behind a moving boat?

We also apply these ideas to the computation: Is it running as fast and using as much memory as we expect? Or is something surprising happening?

DP: Simulation testing is not just insoftware…

Chris Wojtan: We do not have a fancy laboratory where we can run controlled experiments, so we only compared visually to footage that we took from nature, or from other researchers around the world who did the experiments already. In this case, the rules for wave energy and wave speeds are well known, so we were lucky that we didn’t have to do our own real-world experiments.

DP: How long do you think it will take for these new features to be implemented in mainstream software packages such as Blender, Maya Bifrost or Houdini?

Chris Wojtan: This is always a tricky question, because the answer depends on a number of factors that are difficult to control. Sometimes the code that makes it into these software packages is related to social connections (e.g., if we personally know one of the developers, or if a paper author did an internship at that software company), or risk factors (e.g., the code is easy to implement, so it was faster for the stressed-out software engineer to use that one instead of a fancier algorithm that might be harder to code), or communication (how well we explained and promoted our ideas strongly influences the perceived risk), or legal concerns. Our algorithm builds upon state-of-the-art algorithms for two other problems (shallow water equations and deep water waves), so adding our method to a software package will be a no-brainer if those other two methods are already in there. However, if not, it will be a lot more commitment for a software engineer. We also note that our work is still “research” – the biggest breakthrough is a mathematical insight instead of a technical one. Consequently, the code is not optimised, and the new part that

combines things together so nicely is a lot slower and sloppier than it could be if a software engineer really sat down and though about it for a while. That could also make an engineer wait to integrate it into their code until somebody else works out that last bit.

DP: Could you talk about the file types and parameters you used for testing?

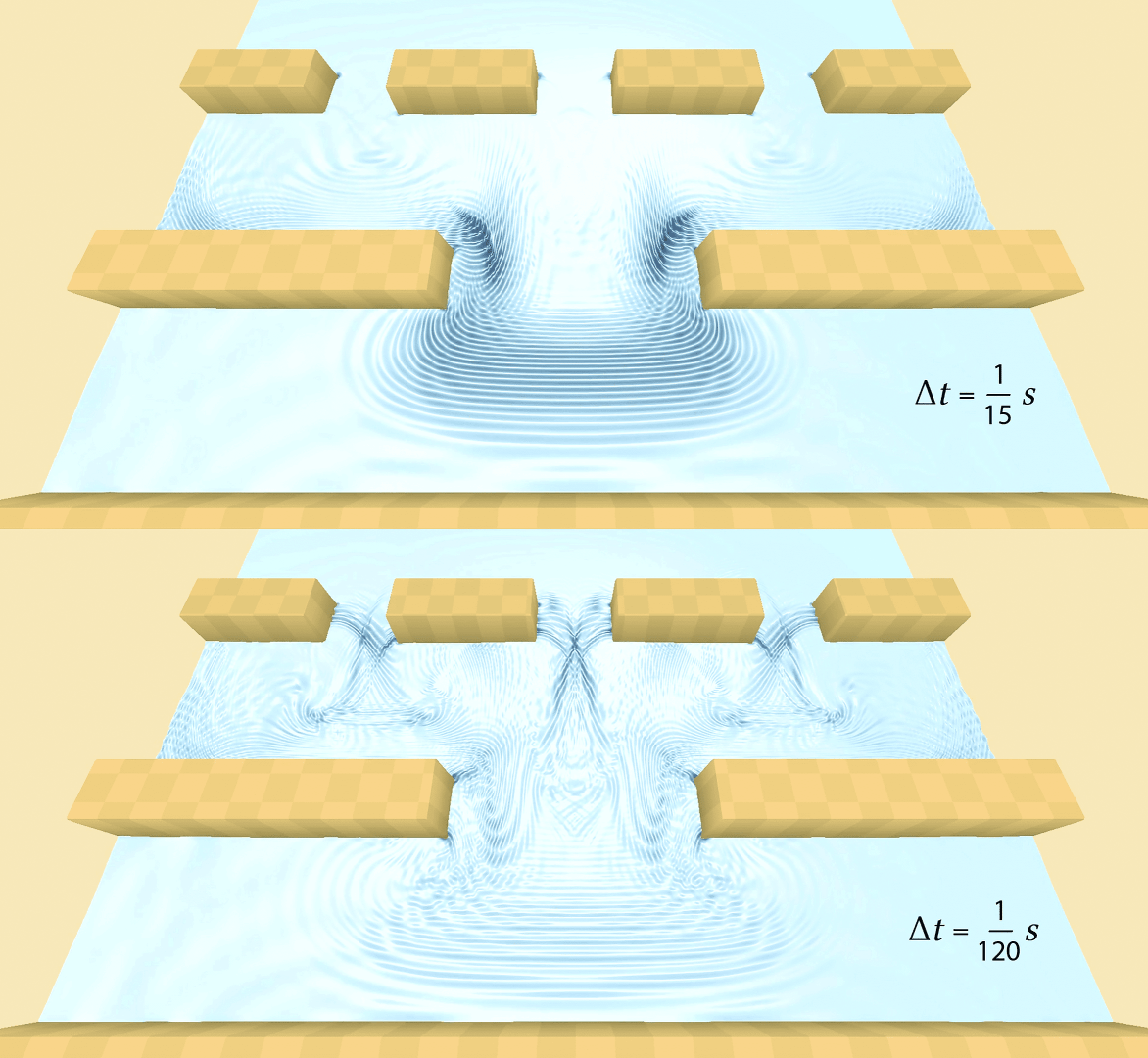

Chris Wojtan: The first author responsible for the work Stefan Jeschke (formerly at NVIDIA, currently at ISTA) made everything GPU friendly. The input files are all image files; the images model the water depth

and height of the terrain, as well as the height and velocity of the water at each point on a grid. The parameters were mostly different image resolutions (how complex is the scene) and time step sizes (how fast should it run), as well as the new parameter that we introduced, which is responsible for categorising water waves into deep or shallow water. We targeted real-time simulation (i.e. video games) in our paper, so the image resolution is only 512×512, with simulations running at 60fps. Bigger and badder simulations also work if you want to crank up the image resolution a whole lot, but you might have to wait a bit longer to get

your animation. We rendered everything in real-time on the GPU, using real-time reflection and environment maps and evaluating surface shaders at every pixel of the scene.

DP: What would be the impact of shaders and lights and so on for this type of simulation?

Chris Wojtan: Surface shaders have a strong effect on the appearance of water; you can see this by looking at a body of water at noon compared to sunset. The grazing angle of the light really brings out lots of tiny variations in surface normals, and make the surface look more detailed. Our simulation method is entirely focused on simulating those tiny, tiny details on the water surface, so we like to use grazing lights to make the small details more apparent. A surface with matte shading and no specular highlights will make it difficult to see small surface ripples, essentially wasting the power of our method.

We make great use of per-pixel shaders to quickly simulate the waves on the GPU, move the wave heights into the correct position, and compute their surface normals.

DP: You already worked with Stefan Jeschke from Nividia to get an implementation for the demo – couldn’t that be translated?

Chris Wojtan: Stefan is always working hard on wave simulation tools and he is probably the world expert on wave animation at this point. He is no longer working at NVIDIA and I’m not sure how much of the ideas and code from previous projects he can publish. But I’ll tell him your suggestion and maybe he will start putting together a dedicated toolkit!

DP: You and your group are based near Vienna, Austria – a famously landlocked country. Why is that?

Chris Wojtan: The reason Austria is landlocked is due to a number of geological factors outside of my control. I blame the dinosaurs, various asteroids, and those finicky tectonic plates. Austria actually has “way” more water than where I grew up in the midwest United States. There are so many beautiful rivers and streams here that regularly hypnotise me when I should be doing something else.

The Institute of Science and Technology Austria, ISTA, is an amazing place to work, because it is so supportive of basic research. We are strongly encouraged to get deep into problems, ask fundamental questions, and try to make big picture insights that might not have an immediate effect but

impact longer term future trends in the field. I contrast this with more applied research towards developing projects or setting short-term goals, because we are free to take big risks without fear of losing our jobs or status. Thankfully, the SIGGRAPH community also appreciates weird new approaches to old problems, so there is a happy synergy between my place of work (ISTA) and the top place to publish our work (SIGGRAPH).

Incidentally, my research group is always looking to recruit new researchers with VFX experience and/or a drive to solve hard problems, so I invite your readers to please get in touch if they are interested in joining us.

DP: What are you working on next?

Chris Wojtan: So many things! Mostly in computer graphics, but we are starting to branch out into fields of biology and mathematics. Here is a short list of projects in progress:

– really big-scale rigid body simulations and fast simulations of granular materials

– fast and robust triangle mesh tools for simulating really big foams and fluids

– a super efficient mathematical theory to optimize shapes for 3D printing

– general tools for converting small-scale simulations into large-scale approximations, like learning from yarn-level cloth simulations to simulate entire large-scale garments quickly

– simulations of biological cells to try to understand how they evolved into their current shapes

– better understanding the mathematical foundations of some numerical algorithms (like “symplectic integrators”)

And, of course, new methods for efficient and super-detailed waves on water and

other deforming surfaces. We have an evergrowing list of all of our projects at bit.ly/ista_vc

and an overview in German at bit.ly/ista_wojtan_current