Under the direction of Barry Jenkins, MPC explored his unique style while bringing the Pride Lands to life. Combining artistry and technology, the team delivered detailed VFX that capture the essence of the story. Led by Production VFX Supervisor Adam Valdez, Animation Supervisor Daniel Fotheringham, VFX Producer Barry St. John, MPC VFX Supervisor Audrey Ferrara, and VFX Producer Georgie Duncan, more than 1,700 artists, production crew, and technologists at MPC created the visual effects for Mufasa: The Lion King.

A few notes on the scope of the project: More than 1,700 artists, supervisors, and production crew contributed to the making of “Mufasa: The Lion King” at MPC. Storage requirements hit 25 petabytes which is the equivalent storage of 5.6 million DVDs. Rendering the film in final quality took 150M hours. It would take a single computer 17,123 years to complete.

DP: How did you first join the project for Mufasa: The Lion King?

Audrey Ferrara: In summer 2020, right in the middle of the pandemic, we received the first draft of “Mufasa: the Lion King” and I was asked to breakdown the environments part of the script. This was the first point of connection with the project. Later on, I was asked to supervise the post-production visual effects, MPC side, and I accepted. How can you not say yes to this story…… But I have to say, the challenges were big and it was my first time supervising such a massive project. September 2021, after working closely on the pre-production side with Mark Friedberg, the production designer, we headed to LA for the shoot!

DP: What was the size and structure of the team involved in creating the visual effects for Mufasa?Audrey Ferrara: In total, we had a staggering team of 1700 artists who played some part on the project, coming from different sites across the world. We had to structure the project in multiple “departments”, not quite yet in the sense of a traditional company structure…. Think of it as an expert department dedicated to the movie. So we had a department for animation, itself split into 3 units, with 3 anim supervisors (Dan Blacker, El Sulliman, Ruth Bailey), due to the sheer volume of work. We had a sets department, supervised by 2 sets supervisors (Andrea Vincenti and Luca Bonatti), who were in charge of all the 77 environments: modelling, texturing, and also the greens library, used to set dress those sets. We had one character supervisor (Klaus Skovbo) in charge of all the animals (118 unique species), one FX supervisor (William Banti), dealing with the water work, snow, fire, clouds….. One techanim supervisor (Will Fife), in charge of animals and dynamic foliage. And one lighting supervisor (Francois de Villiers), who worked with James Laxton, the cinematographer, to understand his style and his typical light-rigs choices.

When it was time to gather everything in comp, we split all the shots in 3 comp units, with 6 comp supervisors (Luke Bigley, Adam Arnot, Anuj, Wineeth, Sandesh, Sourahb), so once again we could work in parallel, and deal with the volume. Lastly, we had one stereo department, supervised by Nicola Casanova, who set up eye divergence early on, at the layout process.

What is interesting is the structure of the show evolved during the 4 years it lasted, following its needs at certain times, so it changed along the way. We had to be flexible, for the schedule and anything else that we couldn’t foresee. For example, we didn’t start the show with 3 anim units straight away… We started with one, then the second one came along and finally the third one later on.

DP: Can you walk us through the technical pipeline for the movie? What software, tools, or workflows were critical to bringing these photorealistic animals to life?

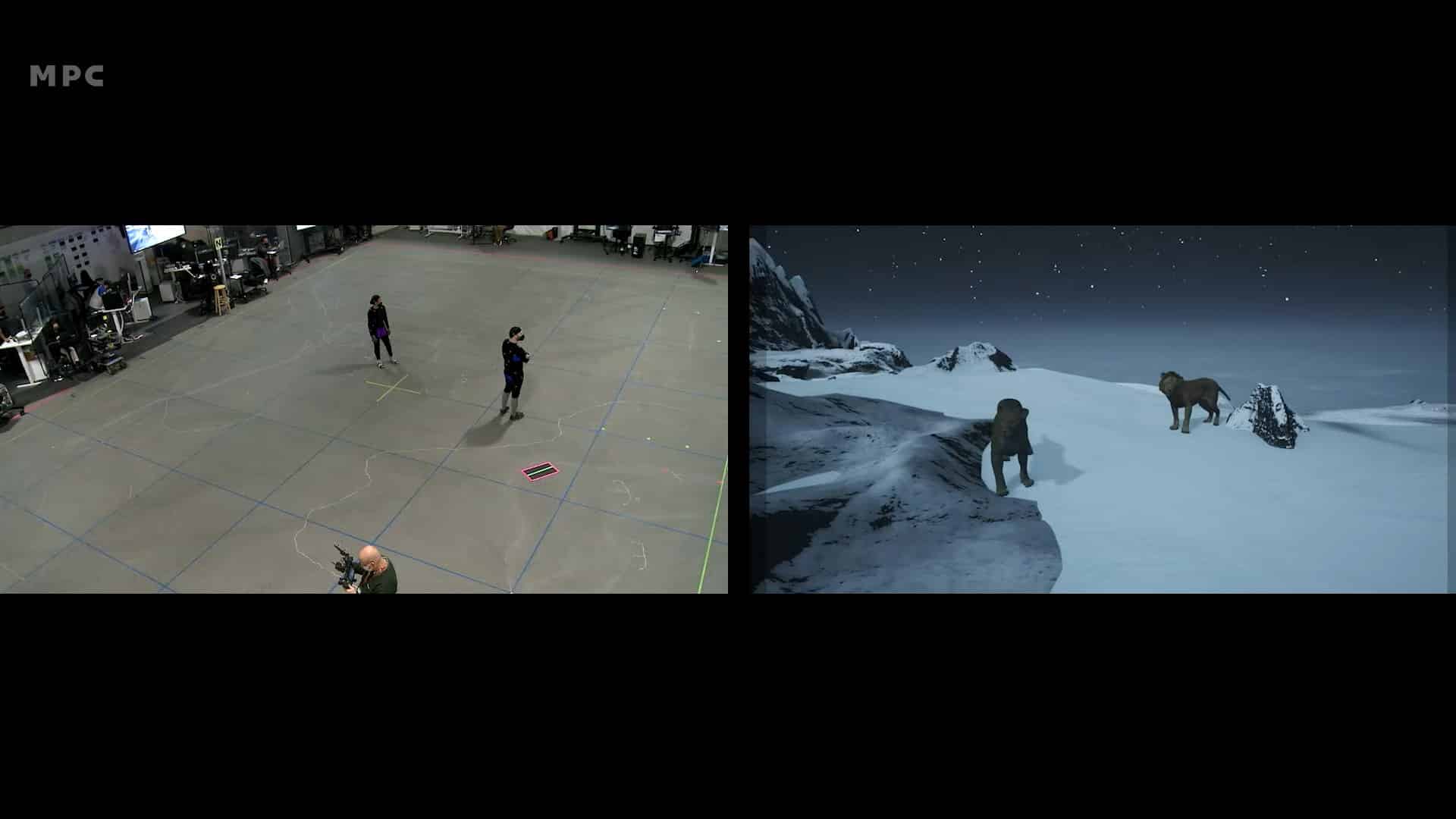

Audrey Ferrara: On this film we start using Unreal Engine from Epic Games. Using a game engine software creates several new kinds of workflows. First, because we started the film during a pandemic, we had to figure out a way to start collaborating on full-cg world building while in different cities (London, New York & LA). Unreal has a kind of “multi-player” function in its editor that facilitates several computers networking together to view the same content. And then Unreal’s realtime performance allows for the use of VR headsets, which really helps immerse during the exploration process.

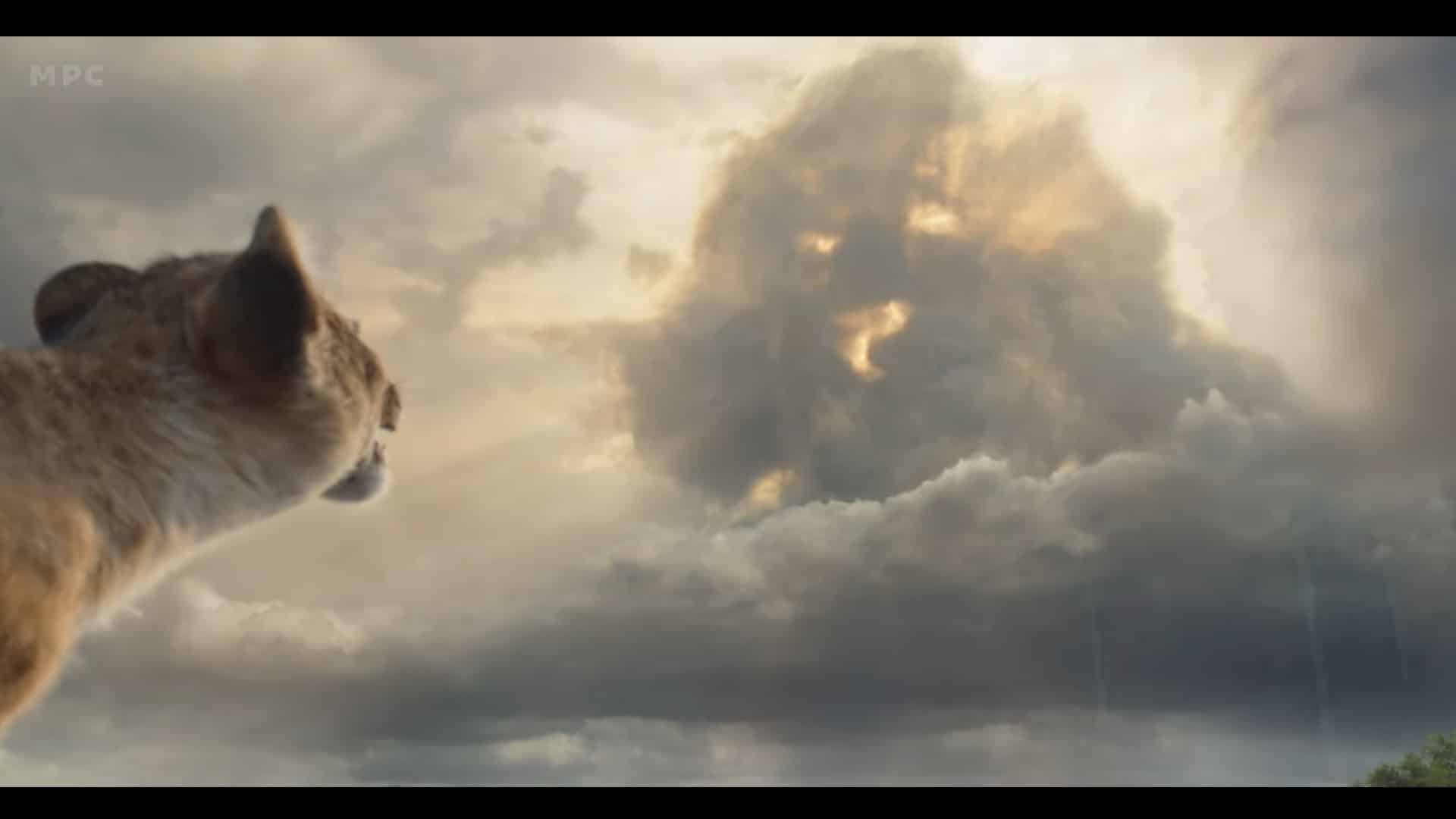

We also used Unreal to do our virtual shooting process. Once our shoot is completed, we have a rough layout of our movie in this game-engine type state, and we download each take as data into the MPC main pipeline to start creating all the photo-realistic work. We still use Autodesk Maya as a main workbench. This is where animators do their job, and where a lot of shot construction happens. We use Houdini for complex simulations for water and fur movement, as well as the procedural creation of very complex environments phenomena, to finish the 3D work on shots. All of that then ends up in Renderman. We have teams at MPC who are always updating material shader definitions based on the latest understandings, and we saw great improvements on the rendering of fur in particular for this show. Lighting work in Katana for final lighting setups and pipeline. Finally we use Nuke for the ability to really get into both the subtleties of how a photographic looks, but work on complex ideas like how the sun moves through atmosphere, or how a lion made of clouds changes over time.

All in all its a big chain of software, one for each specialist job. Within each commercial software, of course there are years of MPC tools that aid in tasks, or create pipelines that flow the data along the chain. At MPC there are so many pieces of software that complete the whole studio, it’s fairly mind boggling, but it’s a powerful system that sits on top of some very big infrastructural layers which gives us the ability to operate at scale, and globally.

DP: What were the biggest creative challenges on this project, and how did the team overcome them?

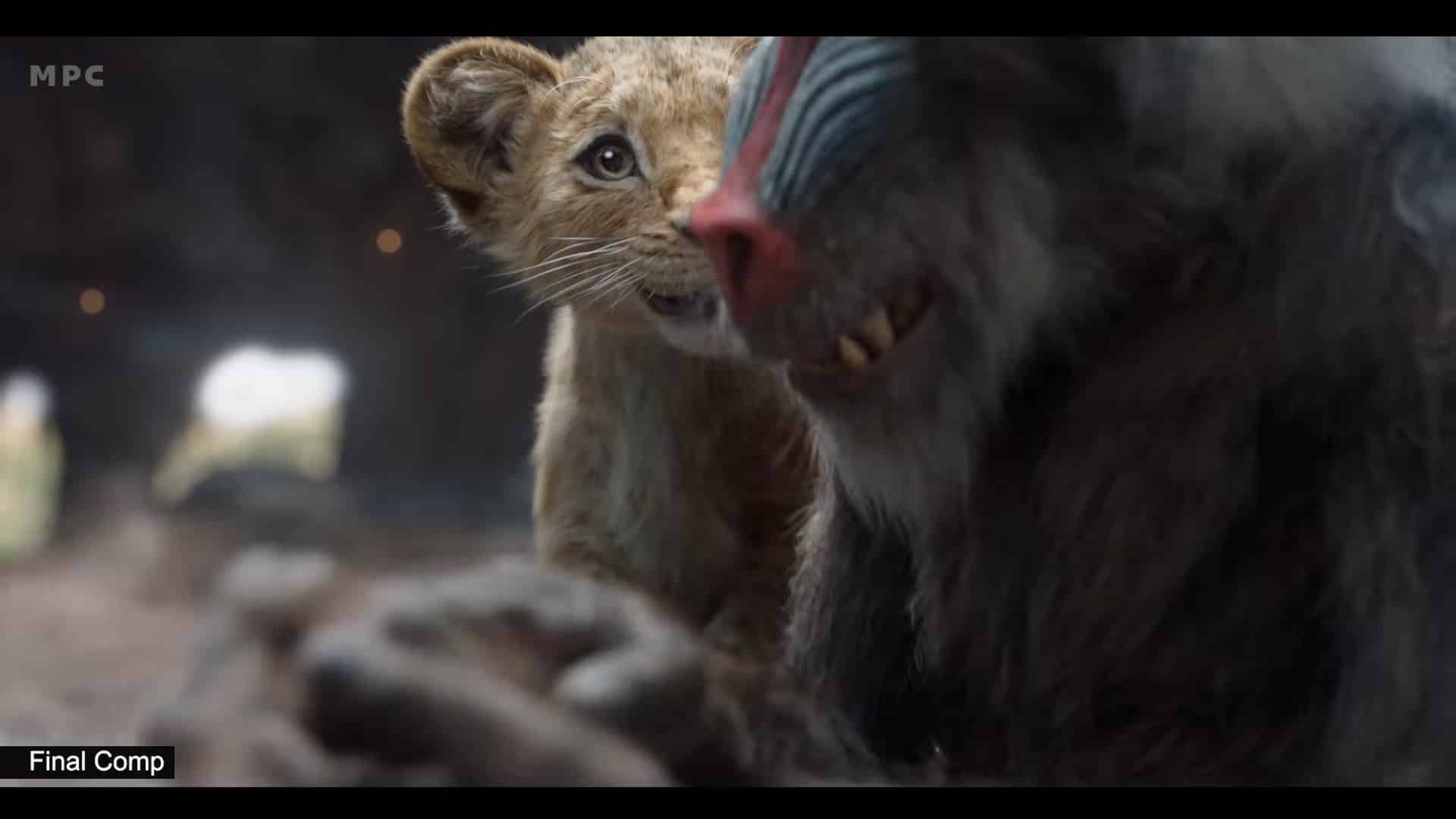

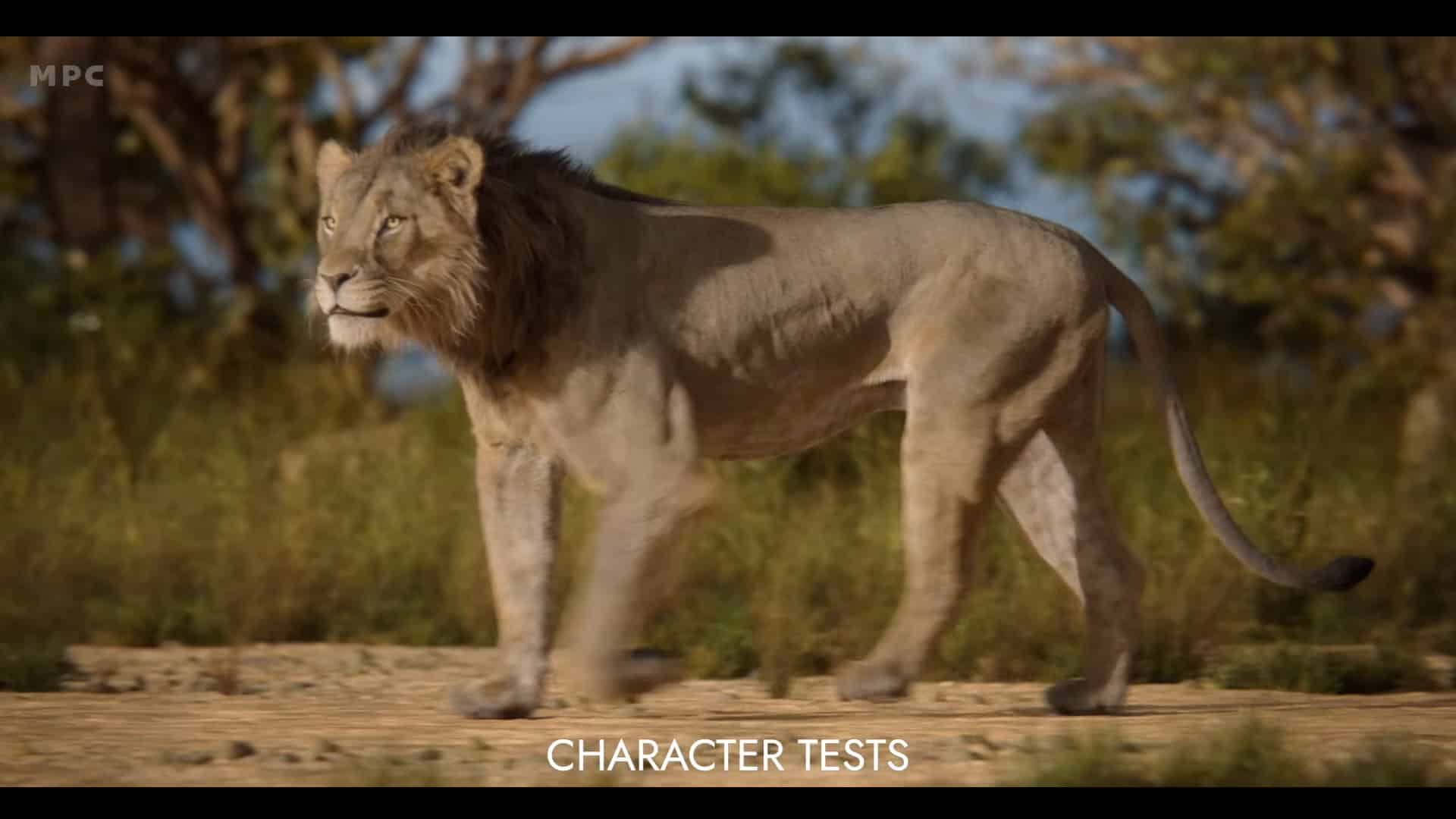

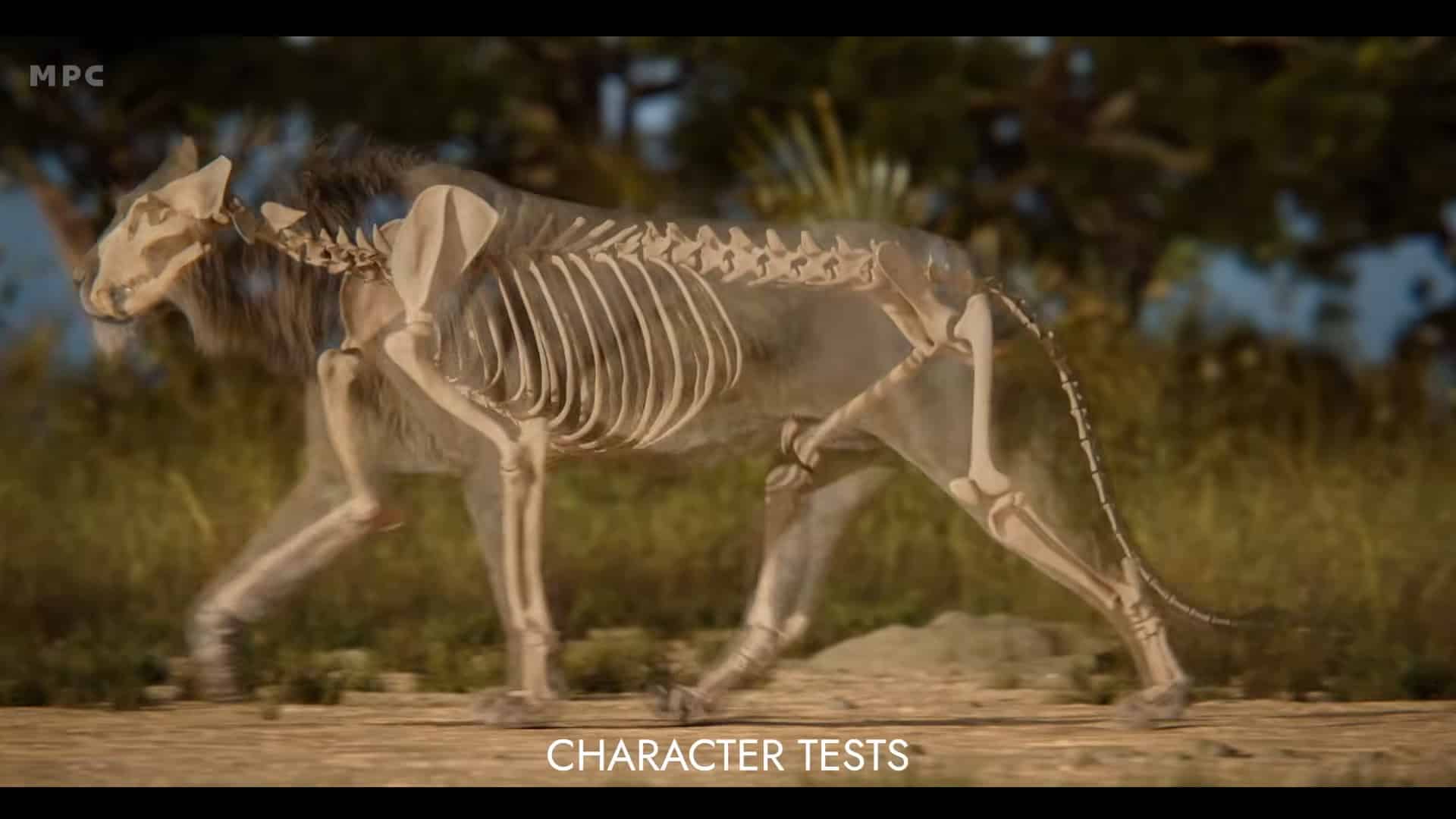

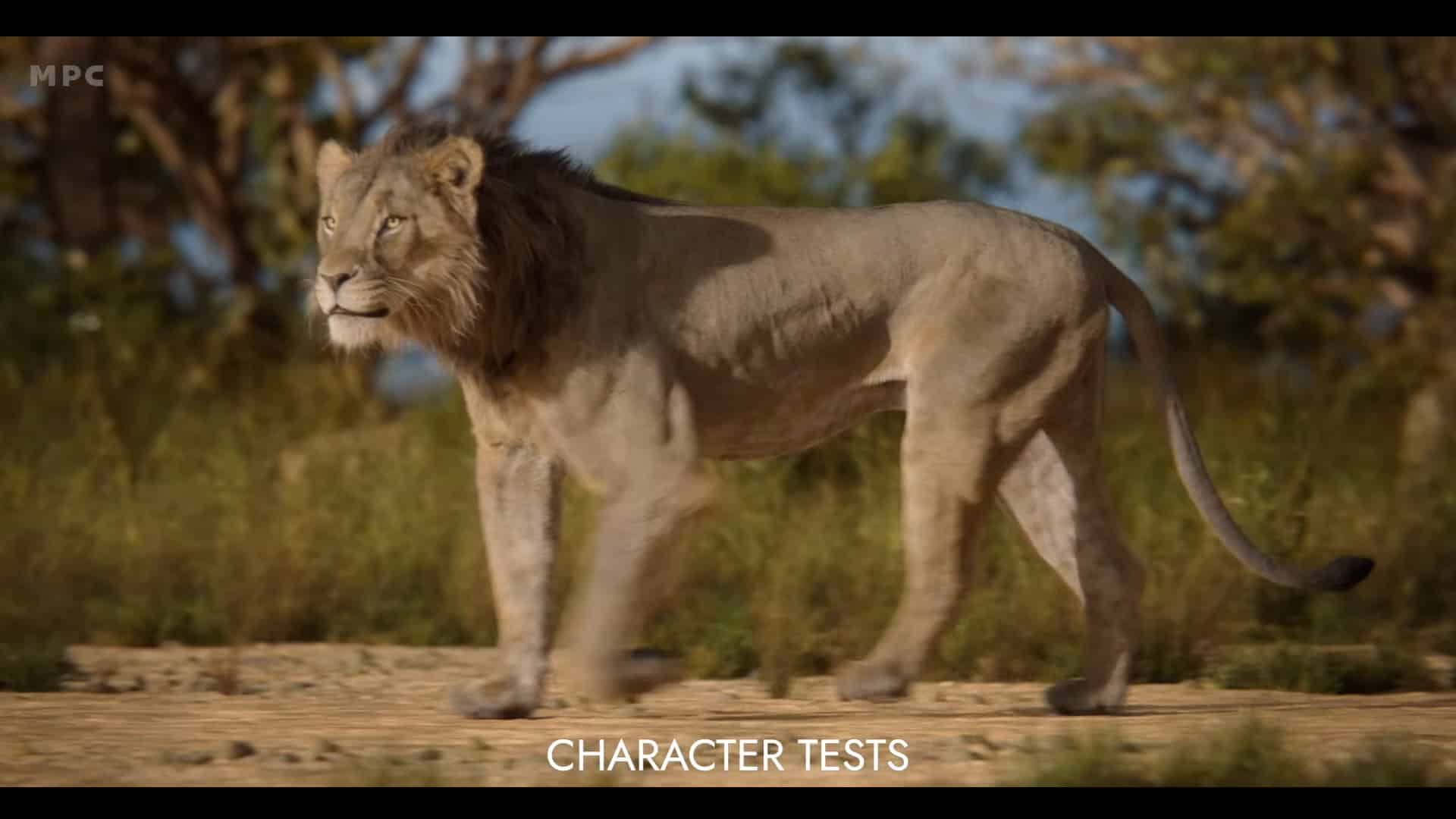

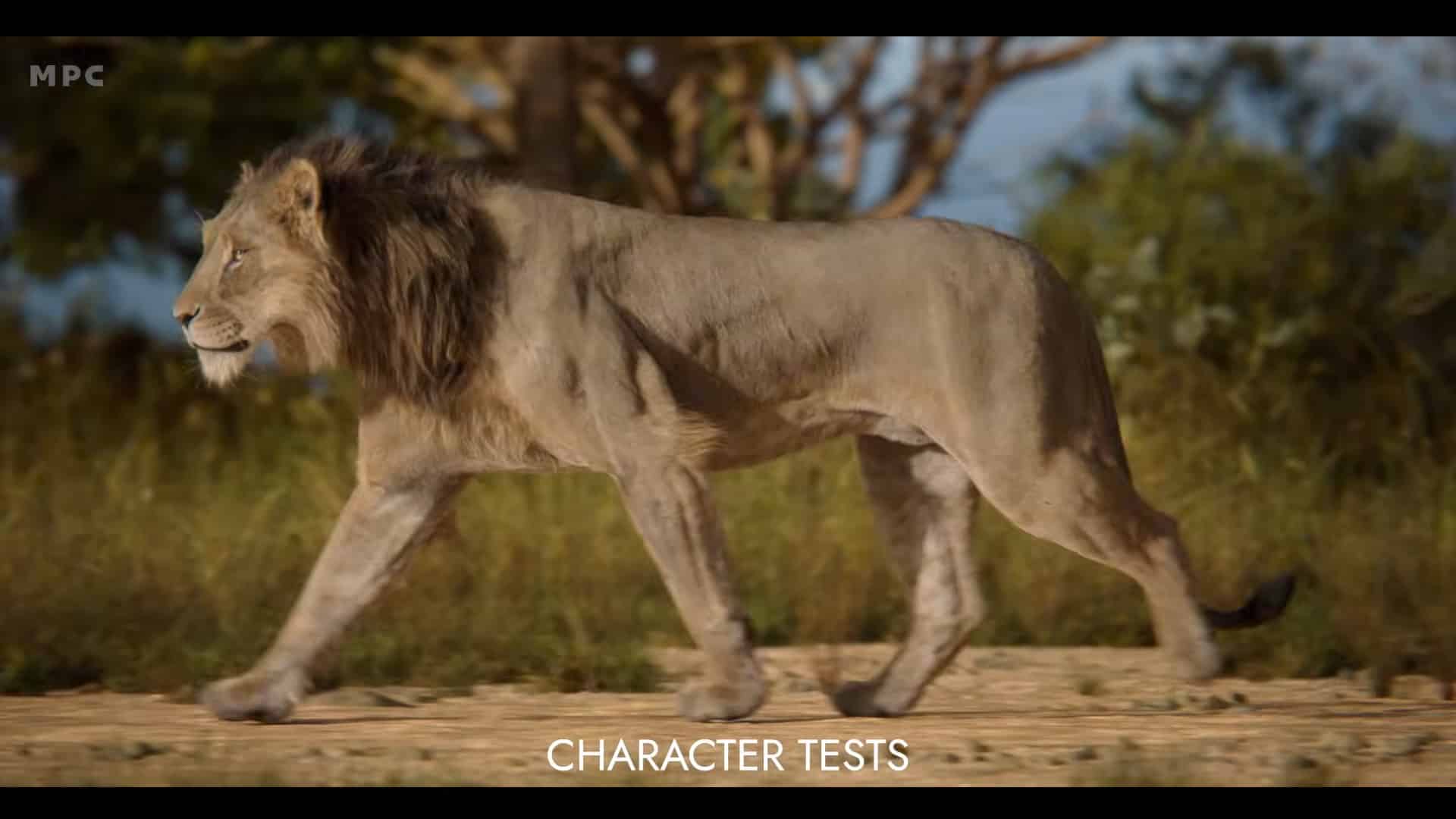

Audrey Ferrara: One of the first challenges was to make all the characters relatable and engaging emotionally: from intense emotion, to very subtle reactions. Iin order to offer the animation team all this range, the MPC character LAB supervisor, Klaus Skovbo, pushed the quality of the model to the next level. The models saw a dramatic increase in the detail, represented in geometry as more and more polygons, as well as the hair count on each character. MPC also reworked its fur pipeline from scratch and developing LOMA, a new fur system. For example: Each lion had over 30,000,000 hairs to achieve the realistic look

of fur. Mufasa’s mane alone had 16,995,454 hair curves.

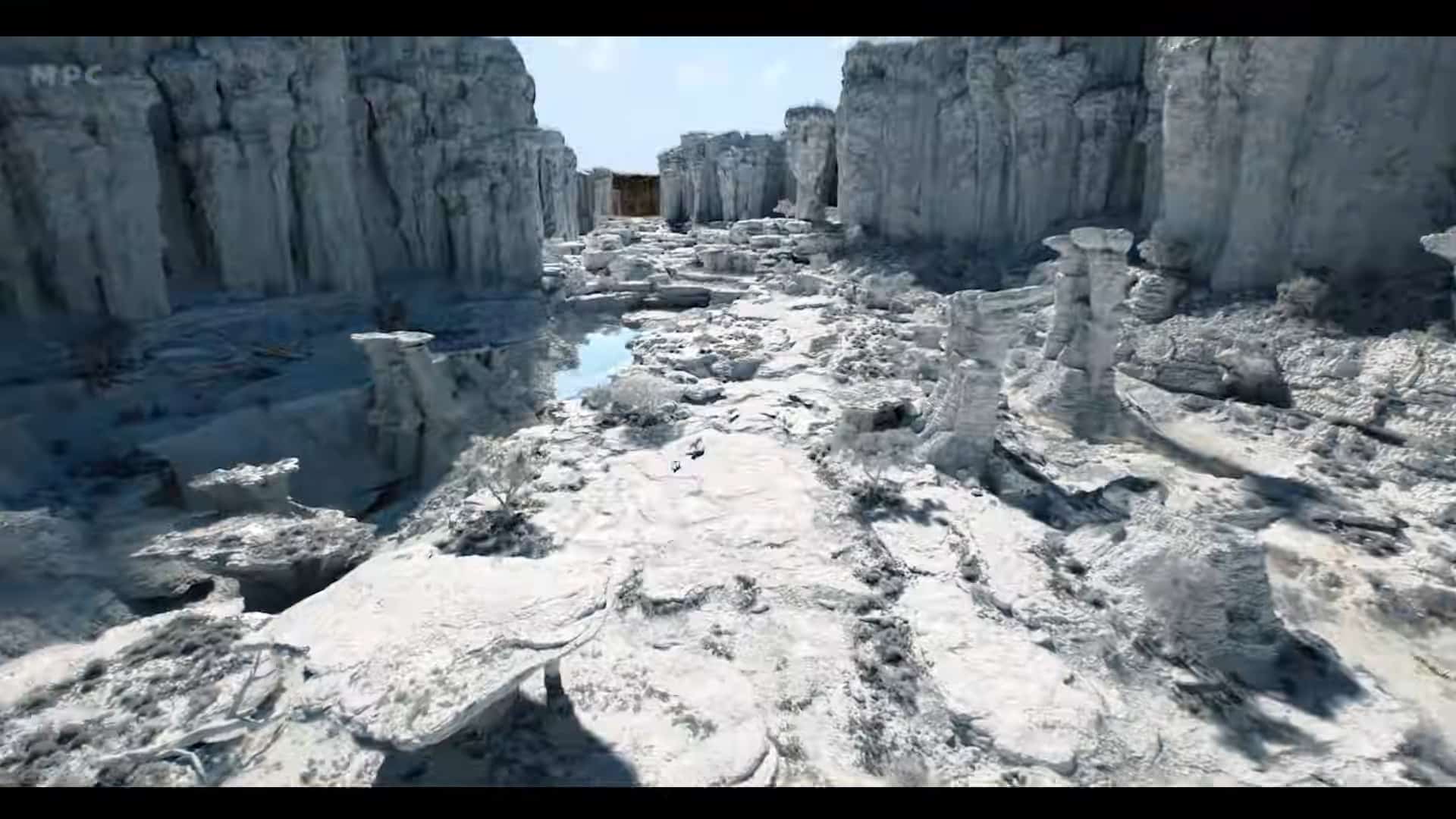

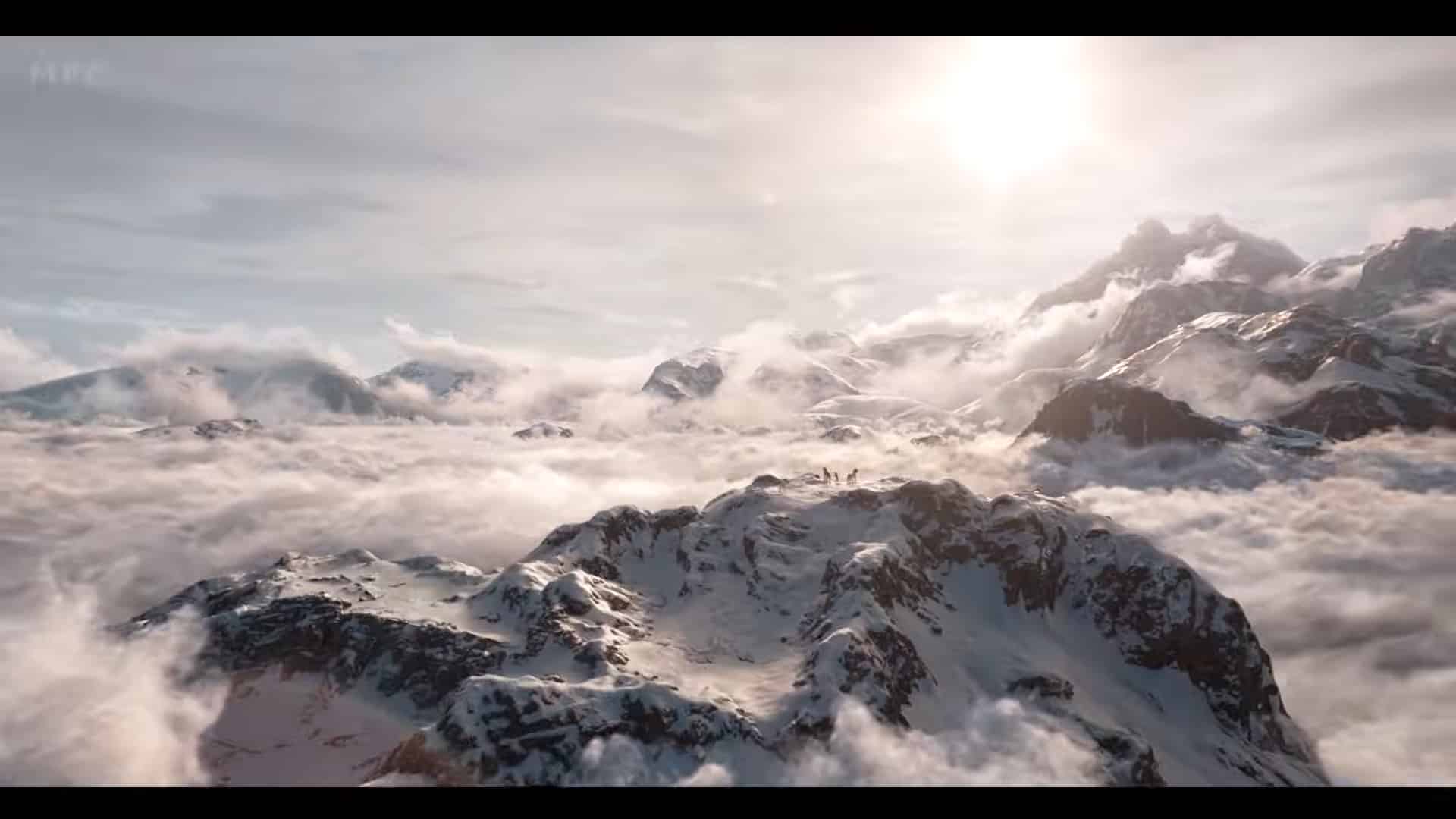

DP: The environments in Mufasa look breathtakingly real. How did the team approach designing these spaces to feel immersive and expansive while staying faithful to the “original” Lion King aesthetic?

Audrey Ferrara: For quite a few years, and now quite a few films, MPC has developed a very complete approach to fully-Cg, 3D world building. Production design is so important on any film, and here we own the responsibility to completely represent Africa, the designed spaces of the film that support camera, composition and photography, and ultimately bring a feeling and tone to each sequence via the look of the world of the film. It’s really one of the single biggest jobs on the film next to the acting.

We always scout and data-gather from real places. We’d been to Africa before for “The Lion King” but this time the pandemic prevented us from making a trip as a team. So we sent local scouts to various locations to data gather and collect our references. This time many parts of Africa donated content for the journey portion of the story.

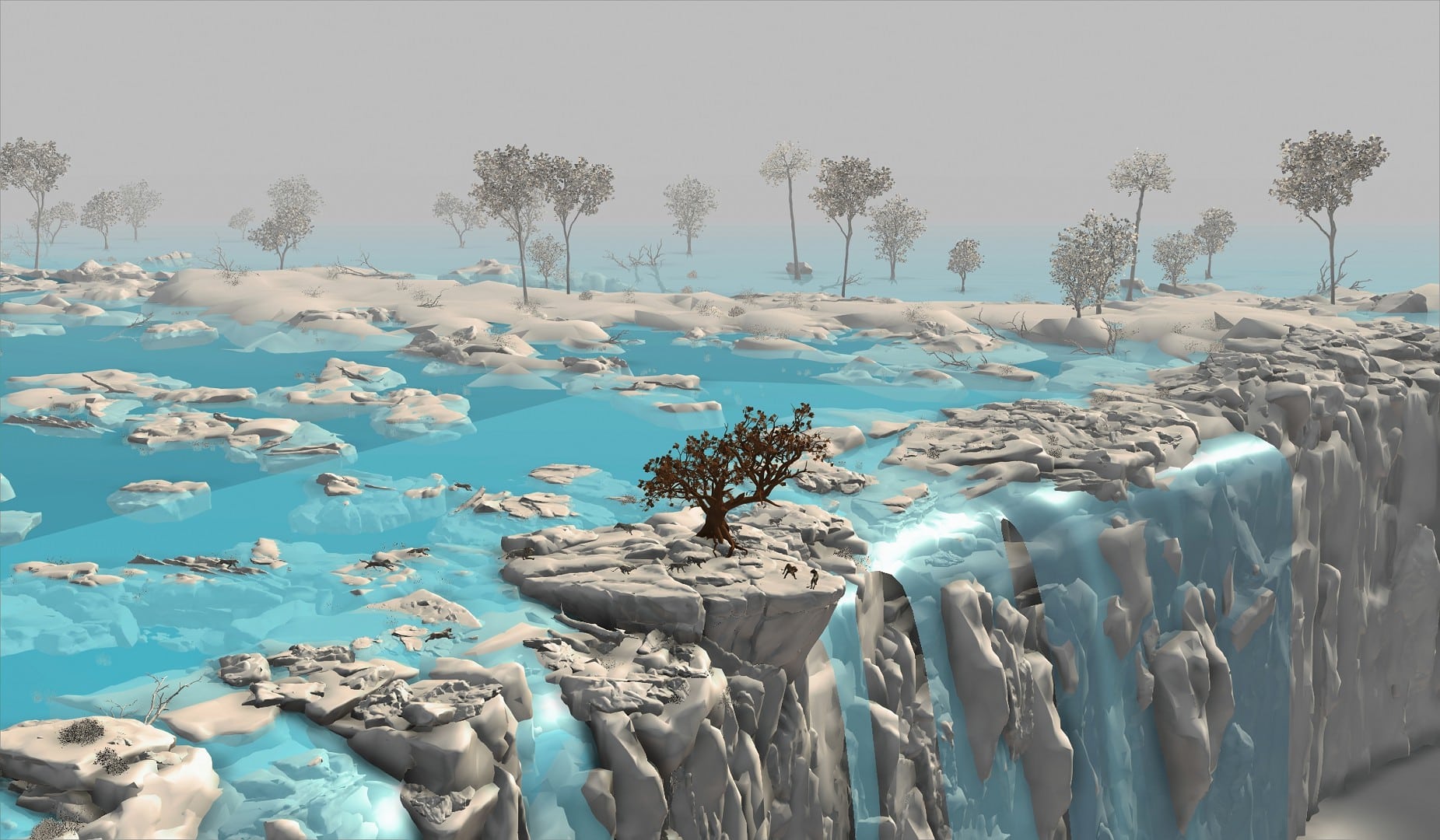

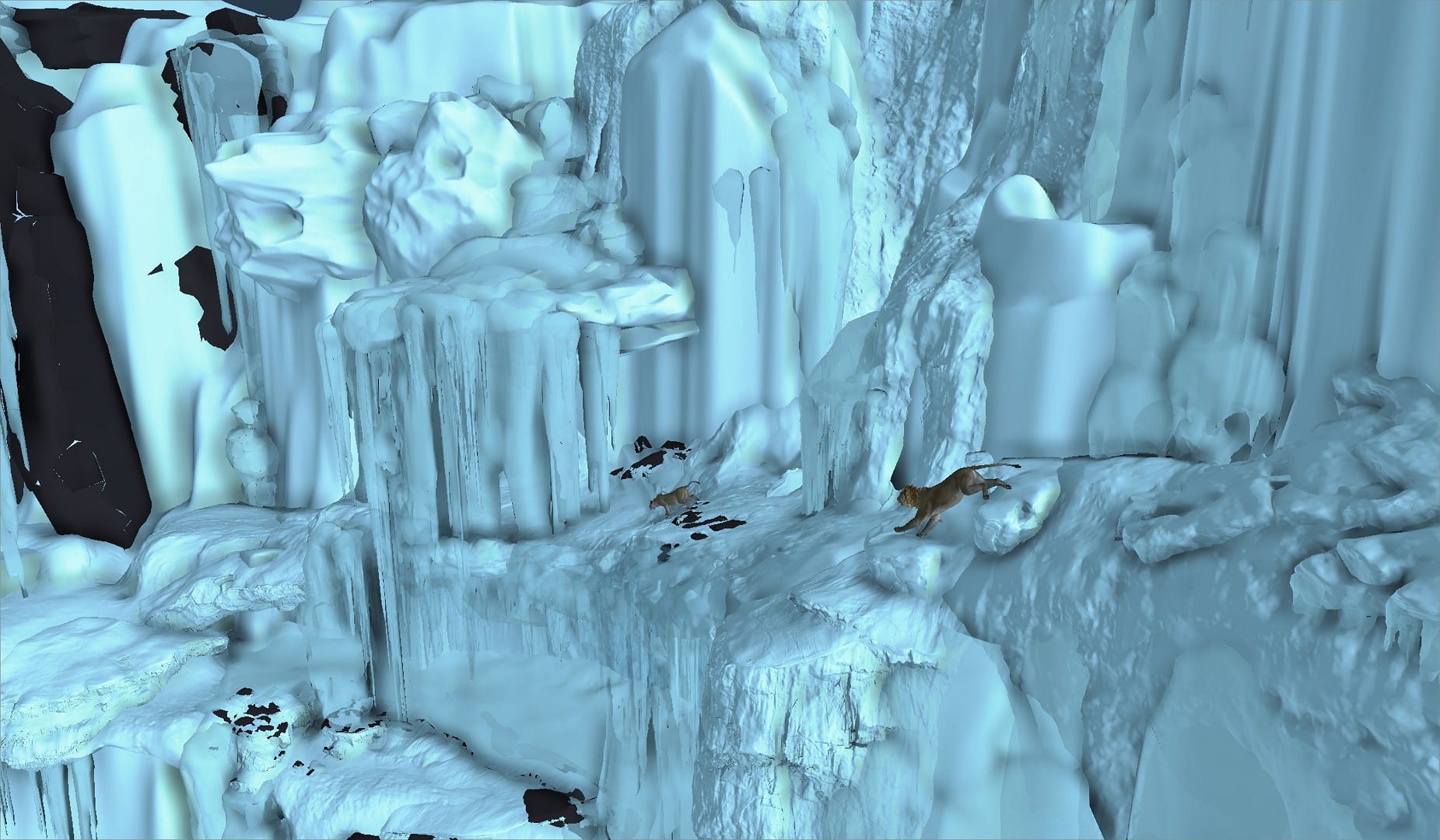

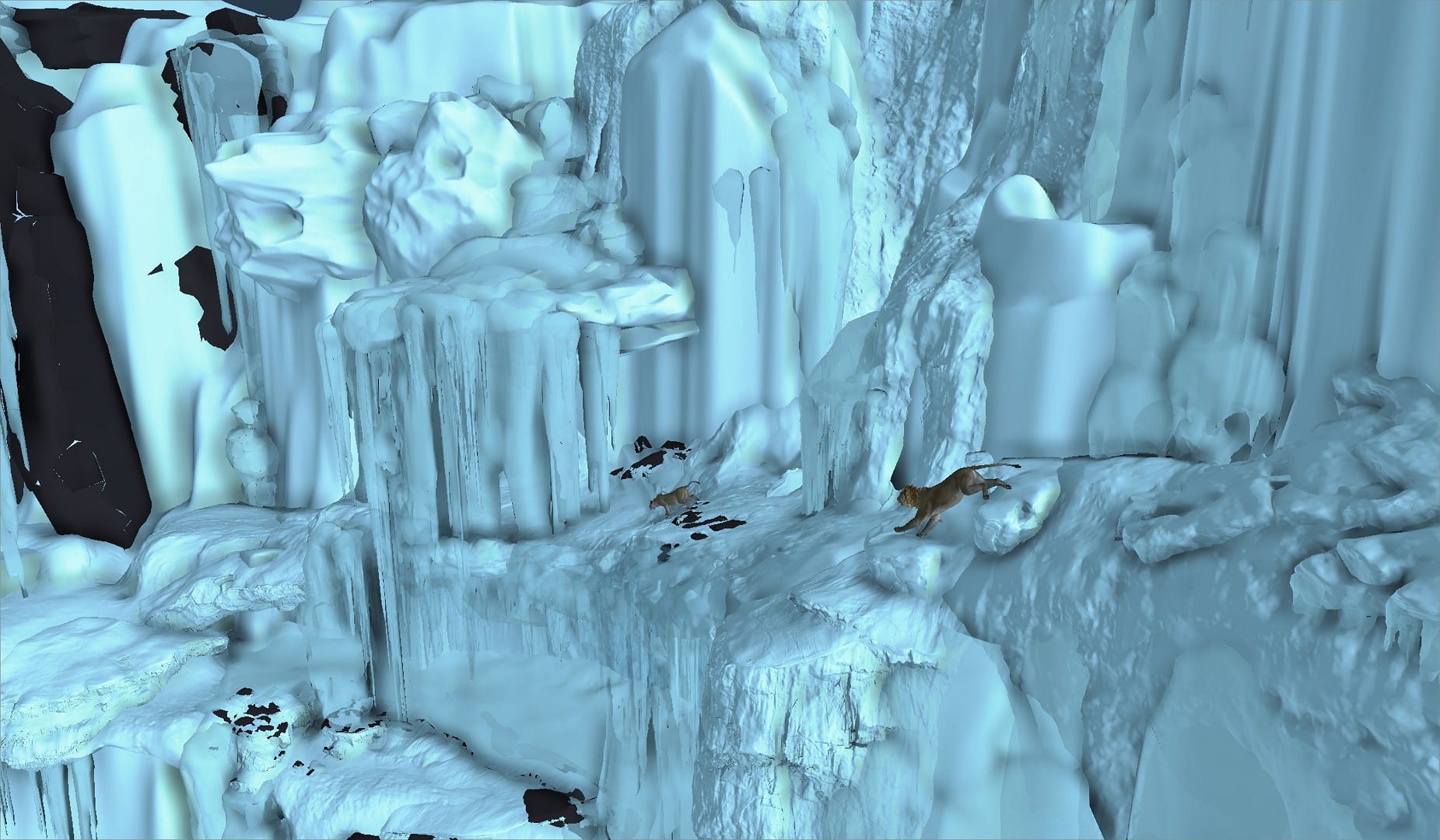

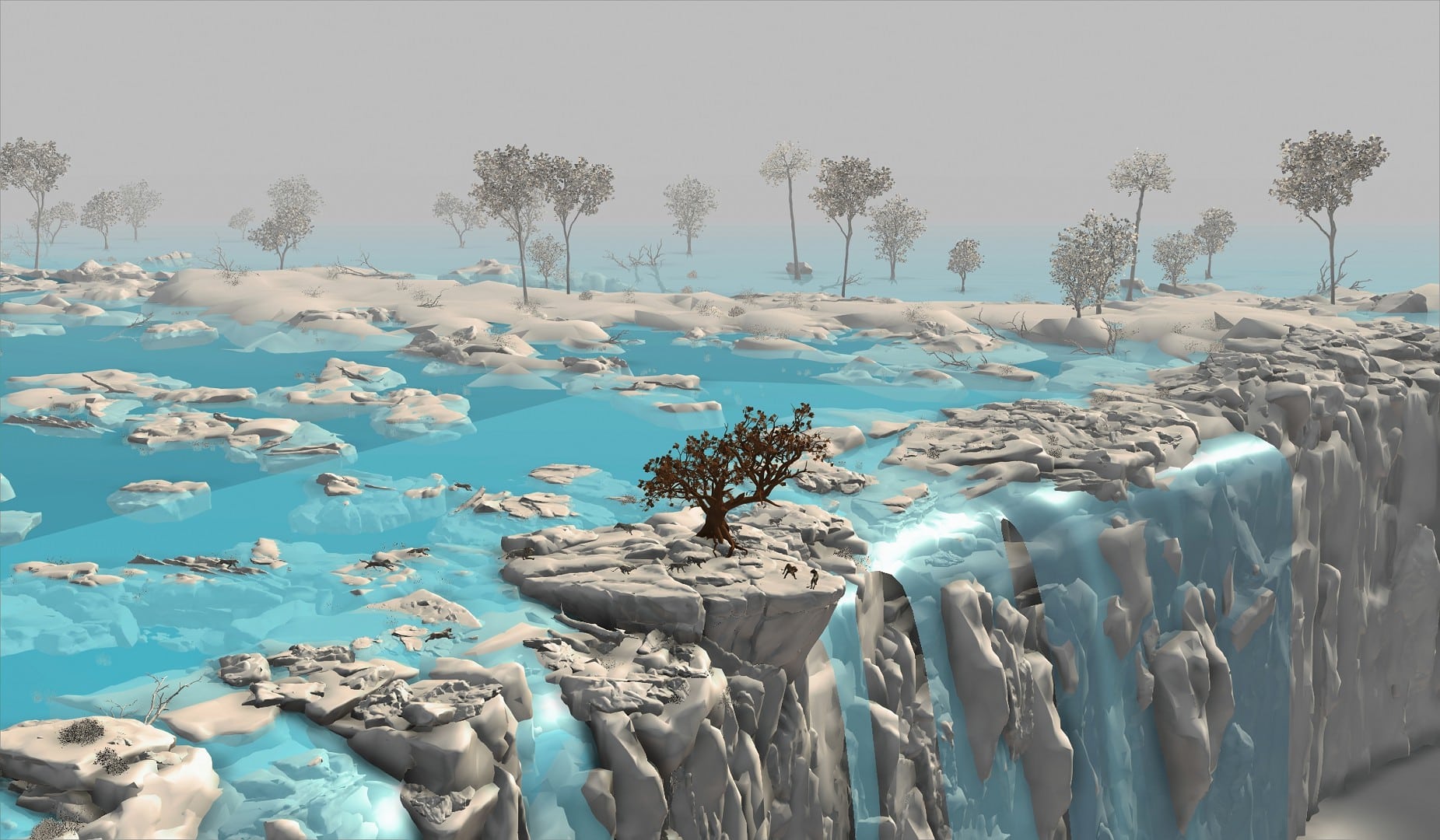

You can think of the world building in layers. There is a library of objects like individual plants and trees and rocks. But for any one location there is also a library of terrain pieces, like modules of the required landscape that allow for complexity near the camera. The entire landscape is usually a sculpted thing, based on reference. So you can think of a valley having an overall sculpt, with modular towers of rock that are resued and arranged, and then set dressing with library objects. Finally, there are ways of combining textures in layers, and procedurally-generated maps for things like weathering and water flow and fine-object scatter distribution, that glue things together.

The team really pushed all of this to the next level for this film. We had more sets, more space to cover, and more variety than ever. For each eco-system, there is a whole period of look-development, balancing the shaders of the landscape for different looks. Snow was a new challenge for this film, and we made an effort to represent the ice crystals and other complexities of icy sheen that builds up from snow that sits for a long time in a cold place. The team really pushed themselves on the entire film.

DP: Iterating on models and assets is often the backbone of a project like this. How much influence did the animated classic have, versus footage from “refrence settings” in reality?

Audrey Ferrara: We don’t really look to the animated films to have a big influence on the new films, other than understanding the mythology and legacy of them. Those films work as animation, and this is supposed to look and feel and relate to the audiences as live-action. Thus we don’t let things like design influence us too much. That said, of course we are all personally influenced by those original animated films, and we love and respect them. We know that they work by giving the audience a heightened sense of storytelling, a magical quality and a sense of beauty and awe, and we aspire to effect people in the same way. So in all our artists’ work, we are very aware of those original films and try to honor them, without copying them.

DP: How did MPC and the director collaborate creatively on Mufasa? Was there room for experimentation, or was the process more about refining a clear vision from the start?

Audrey Ferrara: All filmmaking involves discovery along the way. Our script, and our director Barry Jenkins, have a strong starting point of view about what the movie is about, the feeling to create, and a kind of mode of storytelling. Barry has more than a style, but a kind of voice, a way of telling you a story from a very intimate place close to the characters. Sometimes the camera literally swirls close to their faces, as if you put the audience as close as possible to them.

Barry was doing an animated film for the first time so we tried really hard to make the whole process flexible for him. It’s not easy because it’s a huge machine and it takes so many months to go from the idea of a shot to finally seeing a shot become real. But at the many steps of the process, you see more and more, and by mid-way through the making of the film, Barry was really an expert on the process and could tell if things were going to work in the long-run.

Disney as a studio provides the schedule and budget to adapt to change over time. They know the movie will slowly emerge, and that all of us won’t know precisely if it works or what might need improving, until midway. So we are fortunate to have that kind of support and space to improve as we go.

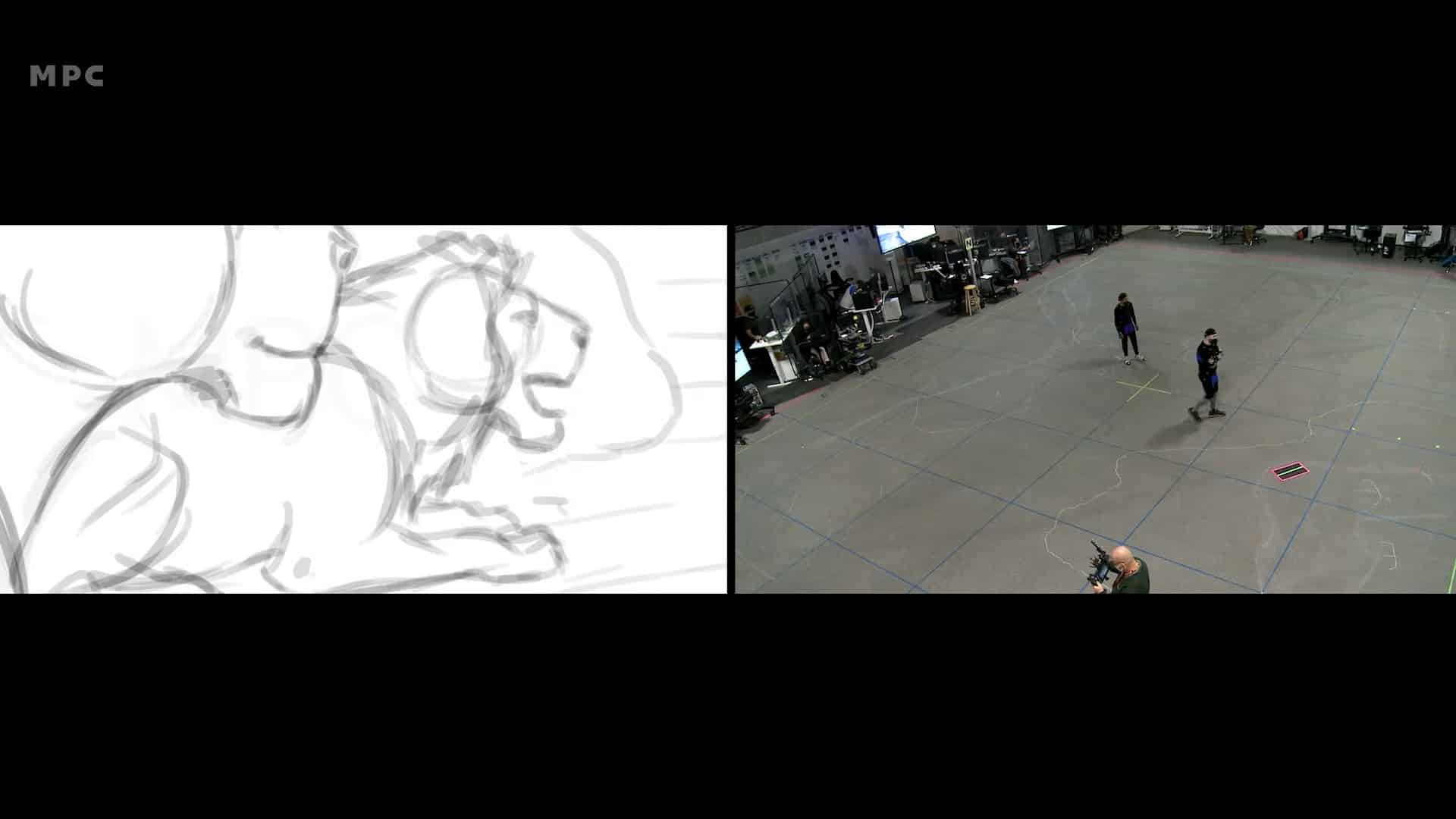

DP: What role did concept art play in the pre-production phase? Did any early designs significantly evolve during production?

Audrey Ferrara: The pre-production phase was crucial in exploring the new environments needed for the story, and how extensive the journey would be for the heroes. Mark Friedberg’s art department did all the concept art for those environments and then proceeded to build them in unreal, in order to allow the director to scout them in VR. The collaboration between art department and MPC was important, so they could use the assets already built on the first movie, and be a starting point for the rest of the development phase. The art department also established the looks of the characters, almost building the genealogy tree of the lions, so they could define family features.

The construction of the sets in unreal provided a high quality previz, that resolved almost every creative challenge early one on the show. In some sequences, the final shots are very close to the intentions in the previz, which shows how well thought the design and previz were.

DP: With your experience on The Lion King and the Jungle Book, what changed in the pipeline since the 2019-film?

Audrey Ferrara: I think when we started Jungle Book, the question was “can we do this today?” Now, this kind of filmmaking is expected. Films like Jungle Book open up how we think about making films, exploring more and more complex worlds to build, how photography and computer graphics mix, and being ambitious. The pipeline in its basic way is roughly the same. We make 3D content, we render it, and we comp it.

I think world building has probably had the biggest evolution. Many of those departments in the industry were called “3D DMP” a long time ago, because it was digital matte painting which was the main tool. That evolved into projections and mixes of 3D and 2D in clever ways. For a film like this, we now are like a hybrid between a game company and a vfx company in this area, because the approach to world building is so intensive and mostly 3D.

Also, it should be said that MPC has to do a lot of things internally to be ready and manage shows of this size and complexity. There are a lot of standards and pipelines and inter-departmental things to help orchestrate it all.

DP: Virtual production is becoming a game-changer. Did you use Unreal Engine or a similar tool for virtual sets, and how did this impact your workflow compared to traditional methods?

Audrey Ferrara: Mark Friedberg and his art department built all the sets in Unreal, so the filmmakers could do the scouts of sets in VR. After a set was approved, james Laxton, the cinematographer would spend time setting up his lights in the scenes, getting ready for the shoot. Unreal offered an incredible flexibility for the filmmakers, allowing them to walk the environments, art direct live the spaces or the action of the lions, thanks to the quadcap tool developed by MPC, or to change the lighting live if necessery.

Any kind of reshoot was also easy to do, since we just had to bring up the desired scene in unreal, and shoot whatever was required.

DP: Expectations for photorealism are higher than ever. How did MPC approach creating assets in 2024, and what new techniques were implemented to make them even more believable?

Audrey Ferrara: Yeah, films like this have many kinds of assets, from props and ground-scatter items, 3D set components with multi-layered texture shaders that are very procedural, to the intensity that is a 3D character who can act and interact with its environment. They all have to be unified by a quality and visual standard or they don’t render together, and that’s a huge challenge. The teams at MPC attack the problem with a bunch of different techniques, but in the end it has to be art directed and CG-supervised by top talent who understand what ‘good enough’ is for these films, and have the artistry and techniques to back that up.

For Mufasa, MPC developed a new fur pipeline called LOMA. It allowed the team to have more fur, better control of the curves of the hair, and more precise simulations. The different weather conditions throughout the movie resulted in new challenges for the techanim team: drenched fur, snow covered fur, close ups of lions fighting with their manes interacting with each other etc…..

Mufasa has 600,000 hairs on his ears, 6.2 million hairs on his legs, and 9 million hairs covering the middle

portion of his body.

DP: The lighting and atmosphere in Mufasa are stunningly diverse across scenes. What was your approach to crafting the look and feel of the movie, and how much of this was driven by technical tools versus artistic intuition?

Audrey Ferrara: James Laxton, the DoP on the movie, spent long hours defining the lighting in every scene for the shoot, aided by the onset lighting supervisor Sam Maniscalco. He chose carefully each single sky, from an HDRI library provided by MPC, and set up all his lights. In parallel, MPC’s lighting supervisor, Francois De Villiers, explored test shots, in order to get familiar with James’ lens choices and style. This happened way before we received the sfirst turnover shots. It allowed us to do our homework with James, and be ready with the shots were coming our way. The continuity between pre-prod, shoot and post-prod really helped keeping the lighting team on brief throughout the production.

One amazing thing about James’ style of lighting is that he very rarely “tweak” or moves around his set up. Which is an amazing advantage in post-production, when you have a consistent lighting throughout an entire scene. It really helped the MPC team to keep lightrigs clean and consistent .

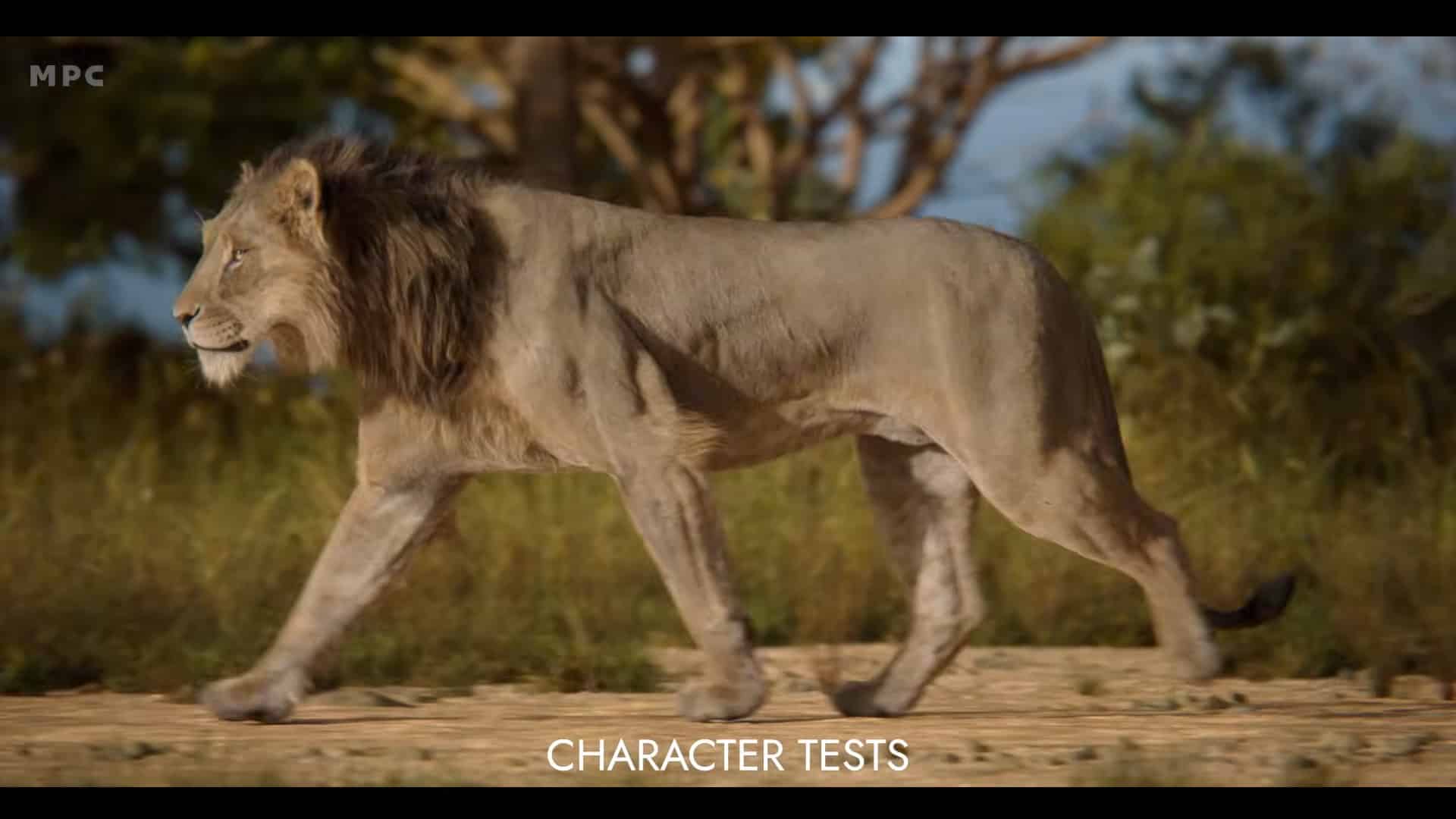

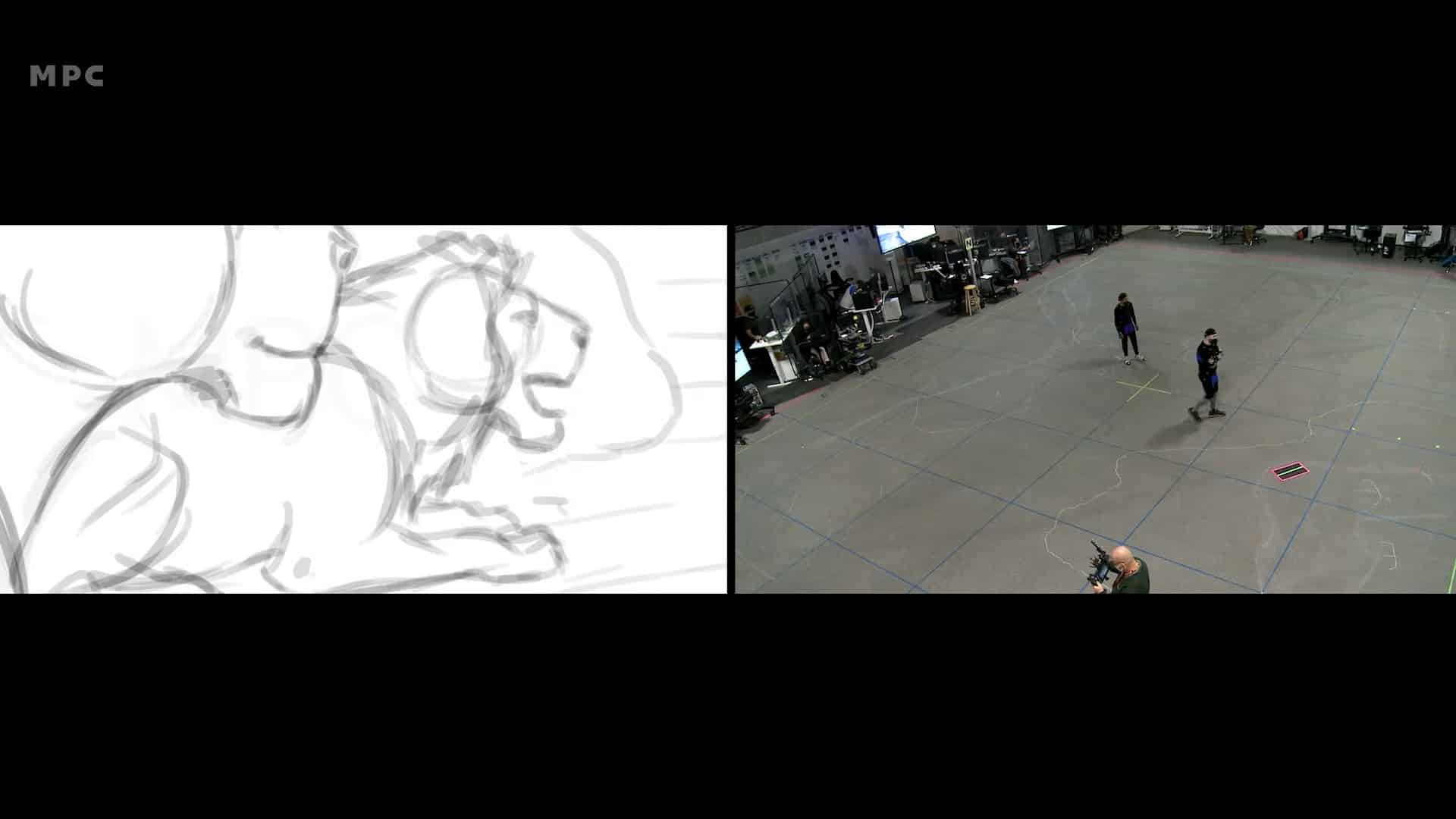

DP: Motion capture was usedin creating the lifelike movements of Mufasa’s characters. How did you integrate mocap data into the pipeline to achieve something so natural-looking yet entirely digital? Audrey Ferrara: Motion capture was used for our “quadcap” new tool for the shoot: with this tool, the lion front legs would “snap” onto human legs, so Daniel Fotheringham, our client animation supervisor could act the lion part on stage. The rear end of the animal would be simulated to follow the front, and snap onto the ground. This was the part where motion capture helped for the shoot and blocking the action. But once the scenes were turned over to MPC, the animation team made each single frame of the movie by hand. Everything has been hand animated on the movie, after carefully studying and selecting references for the animals.

DP: You worked on “The lion King”, “Jungle Book” and now Mufasa: What is your asset library like, and how did you approach Mufasa versus something like Passengers or Alien:Covenant?

Audrey Ferrara: I would say the biggest difference between projects like “Mufasa” or “Jungle Book” and “Alien:covenant” or “Passengers” is the volume of work and time really.

Both types of shows can be extremely complex to achieve, but on a movie like “Mufasa”, you have to keep going for a long time. It’s a big marathon, with a lot of aspects to manage. Everything is bigger: the amount of time, the amount of work, the amount of people working on the show. And it can be daunting sometimes, to look at the mountain of work in front of you that you’re gonna have to climb, a way or another.

I felt so overwhelmed with the work on “Jungle Book” that I had to breakdown everything, and take one task at the time, to make it manageable.

So, it is my first advice when a junior starts on a show like this: one step at the time, but keep the bigger picture in the back of your head, so you know where you’re going. And that they’re not alone in it. That’s what is great on big shows: there are a lot of people working on it, and you can always find someone that has the answers you need and help you.

DP: Do you have a favorite shot or sequence in the movie?

Audrey Ferrara: My favorite shot ever in the movie is the one where Kiros chases Mufasa in the caves at the end: the shot switches to slow-motion, before resuming to normal speed. This shot is SO cool: the lighting, the animation, the camera, everything is great in this shot. Will definitely add it to my demoreel!

DP: If you could go back to the beginning of the project, what advice would you give yourself?

Audrey Ferrara: “Mufasa” was my first time as a VFX supervisor, on a project of that scale. I would tell myself to trust my instincts and the process, to avoid unnecessary stress.

DP: Without breaking any NDAs, what’s next for you? Are there any new challenges or areas of exploration that you’re excited about?

Audrey Ferrara: Over time I have become more and more driven by design. On this film I was lucky to participate fully in that phase, and I hope to do more and more of it.