When Chaos Labs first showed off Chaos Arena and Chaos Vantage together, the pitch sounded almost heretical: a real-time virtual production suite that skips game engines entirely. To some, that sounded impossible. To others, overdue. We spoke with Chris Nichols, Director of Chaos Labs, about what it means to go “engine-free,” why USD and MaterialX matter when the lights go up, and how Gaussian splats actually behave outside a SIGGRAPH paper. *1

DP: Chris,before we jump into the tech: Chaos Arena and Chaos Vantage together are pitched as a virtual production suite without the usual game engine baggage. How would you describe the idea behind this approach in your own words?

Chris Nichols: One of the biggest issues with virtual production is rendering. There are options that have existed for a while, including working with game engines, but they require you to move to an entirely different platform, use an entirely different ecosystem, and switch to an entirely different pipeline. What we’re doing is focusing on the rendering part in a way that lets you keep your current ecosystem and pipeline.

Using Chaos Vantage and Chaos Arena simplifies the entire process. You can basically just take what you already do and work with real-time content. You don’t need to bring in additional experts or learn new systems, you just do what you’ve always been doing and take it a step further.

DP: Arena and Vantage now support USD, MaterialX, and even Gaussian Splats. Could you walk us through why these formats are important?

Chris Nichols: A lot of times, people are forced into using a specific system or format that puts them in a walled garden. It makes them take additional steps, which just slows everything down. We’re trying to break out of that by adopting open source formats and making things as easy as possible, and the visual effects companies that have begun to accept and support USD and MaterialX have an advantage. With USD and MaterialX, no matter what tools they are using – Blender, Maya, Houdini, 3ds Max, etc. – they are directly compatible with Chaos Vantage and Chaos Arena without needing to convert anything.

With gaussian splats, that’s just a general demand that people want. It also works really well with some of the things we specialize in, especially ray tracing, and it allows us to utilize them more than just a 3D point cloud.

DP: One of the bold claims is that you can work without pre-processing, no baking, no data wrangling. From a technical standpoint, how are you pulling that off?

Chris Nichols: This is a very interesting question. If you’re looking at game engines, which use rasterized rendering, that does need pre-processing, and you do need baking and data wrangling. But if you skip rasterization and go full ray tracing, none of those things are necessary. So they are essentially two separate things that seem similar, but are not. It’s kind of like asking how many miles per gallon an electric car gets, which is an understandable question given that we’ve been thinking in those terms for years, but it’s really two different technologies that work differently.

With rasterized rendering, pixels are free. No matter what the resolution you’re working in, the render times are not affected that much, but adding more polygons slows it down. With ray tracing, polygons are free. So no matter how much geometry you throw at the system your rendering isn’t affected all that much. Alternatively, when you start adding more pixels you need more rays, which slows things down.

What has really changed that allows us to bring it all together is recent technological breakthroughs. That includes AI, which lets us denoise and upscale our renderings at very, very high quality, using something called “ray reconstruction,” which was first introduced in DLSS 3.5 and has since been improved. Ray reconstruction allows us to produce very good renders using smaller resolution bases with fewer rays, while keeping the speed. Add in AI and you can get clean, high resolution results with far fewer rays cast, and significantly fewer pixels. AI fills in the gaps.

With ray tracing, there is no baking. That’s the point. We don’t have to pre-render the lighting, it’s full global illumination in real time. Move lights and move objects, all the lighting follows in real time, no rebaking. There’s also no need for data wrangling, because we can just throw the maximum geometry at everything all the time. We don’t need to create levels of detail, we don’t need to do anything else. We can just say the final asset is in real time and enable that, which basically means one asset for everything across the board.

DP: If I’m an artist walking onto a stage with Arena and Vantage for the first time, what does the workflow look like from setup to shooting?

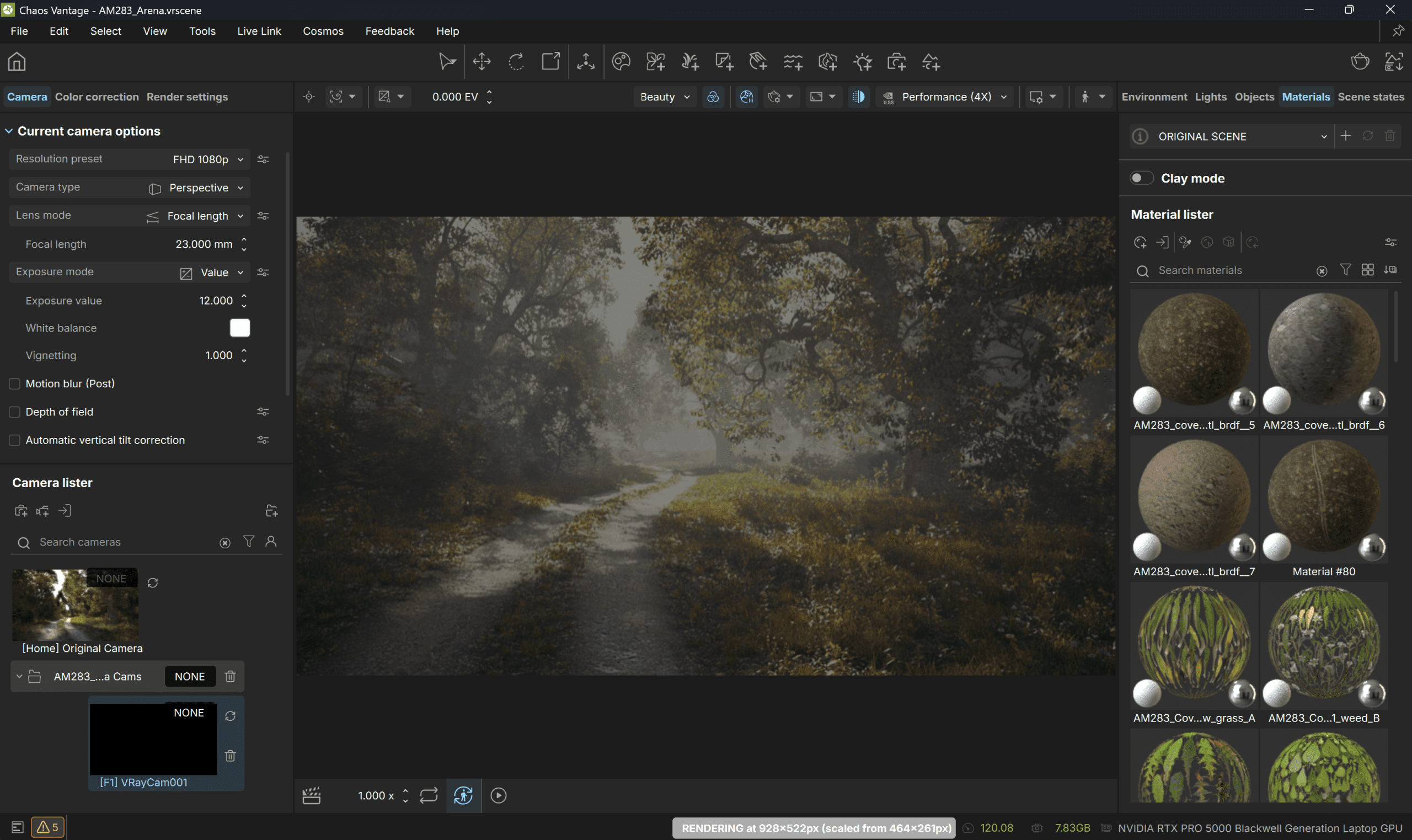

Chris Nichols: It’s actually very straightforward. Vantage itself is a simple program. You can just load your asset into Chaos Vantage as either a .vrscene file or as a USD with a MaterialX system. We also support OBJ and a couple other formats, but those are the most common.

Navigating around is then very straightforward, like most 3D applications. Chaos Vantage is not trying to be a game engine, and it’s not trying to add all kinds of complicated systems. It’s just meant for real-time visualization. So you put your cameras down, move your lights, and move your objects along with a couple of other things. Arena manages multiple instances of Vantage and enables them to operate simultaneously, synchronizing multiple render nodes across a large LED wall. Essentially, it’s saying “here is a master Vantage scene, here’s all the slave nodes that are working in the background.” Arena makes sure everything is synchronized and rendering together.

Arena also adds the camera tracking system you are already using, and we support multiple camera tracking systems. We just enable the protocols. It could be OptiTrack, stYpe, Mo-Sys, or any of those systems, and it enables where the camera is looking. It’s very straightforward and there’s not much of a learning curve. It’s essentially a viewport. This makes it much easier for people to adapt to the system.

That means that a Maya user can easily jump into Arena within a half an hour or less. Same with a Houdini user, a Blender user, or any of those types of tools. Those are the types of artists we are specifically targeting, giving them the ability to continue in the real-time world. That also includes people like directors of photography, because it operates like how a real camera operates. It’s the same language they would use.

DP: Virtual production workflows often involve deciding what to solve in real time and what to leave for post. How does your toolkit support that balance?

Chris Nichols: In the past, there’s always been this break between what you need for offline rendering, and what you need for real-time rendering. It’s two different pipelines, two different teams, sometimes two different companies doing completely different things. We’re looking to make one system that can cross many departments and many avenues simultaneously. We want to offer the same asset that can be used from previs to virtual production to post-production, and make it as seamless as possible. With USD and MaterialX, you are free to use the same asset across the whole production cycle, no matter what DCC, what renderer, and what pipeline you use. It’s your pipeline, and your choice.

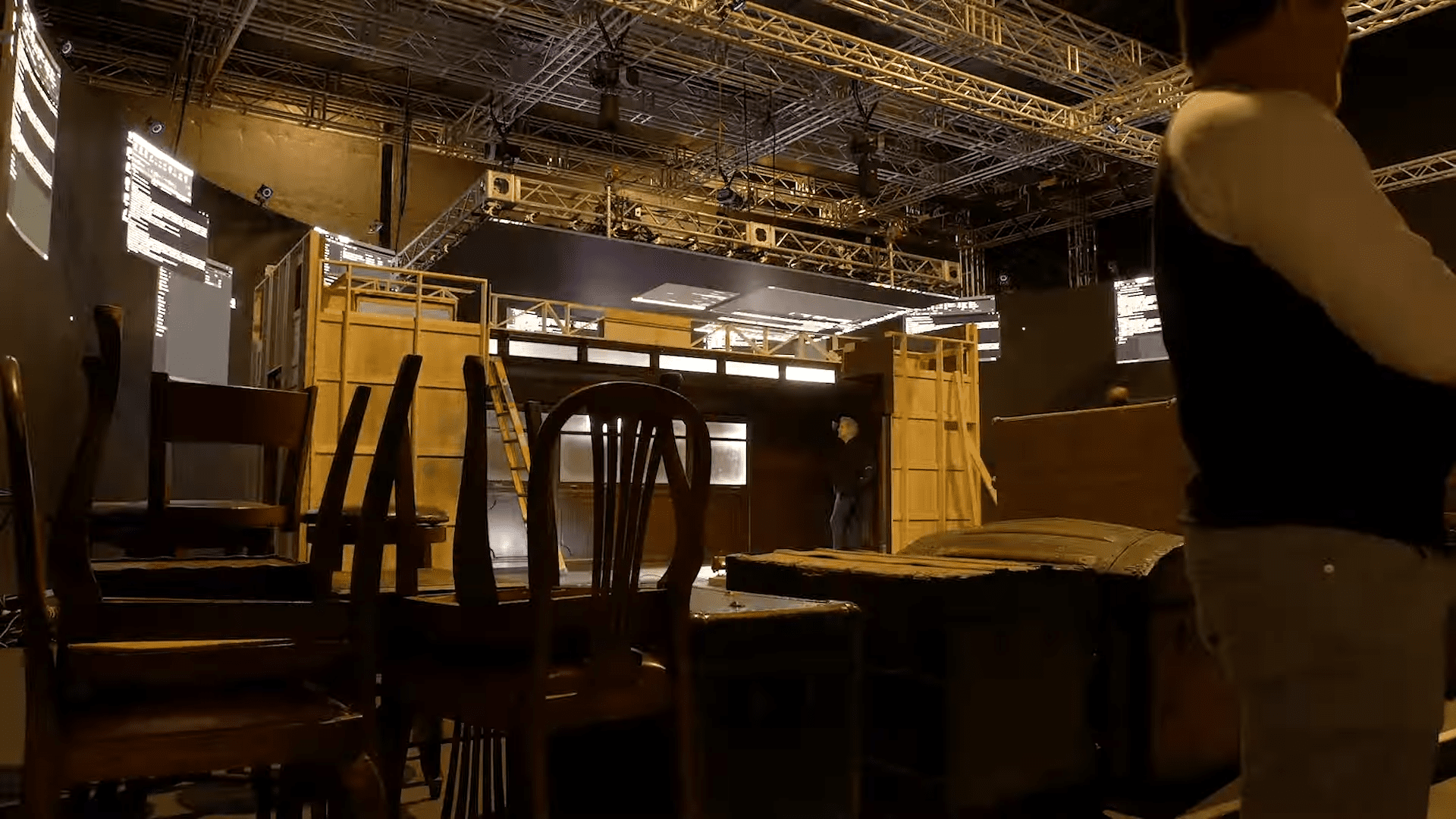

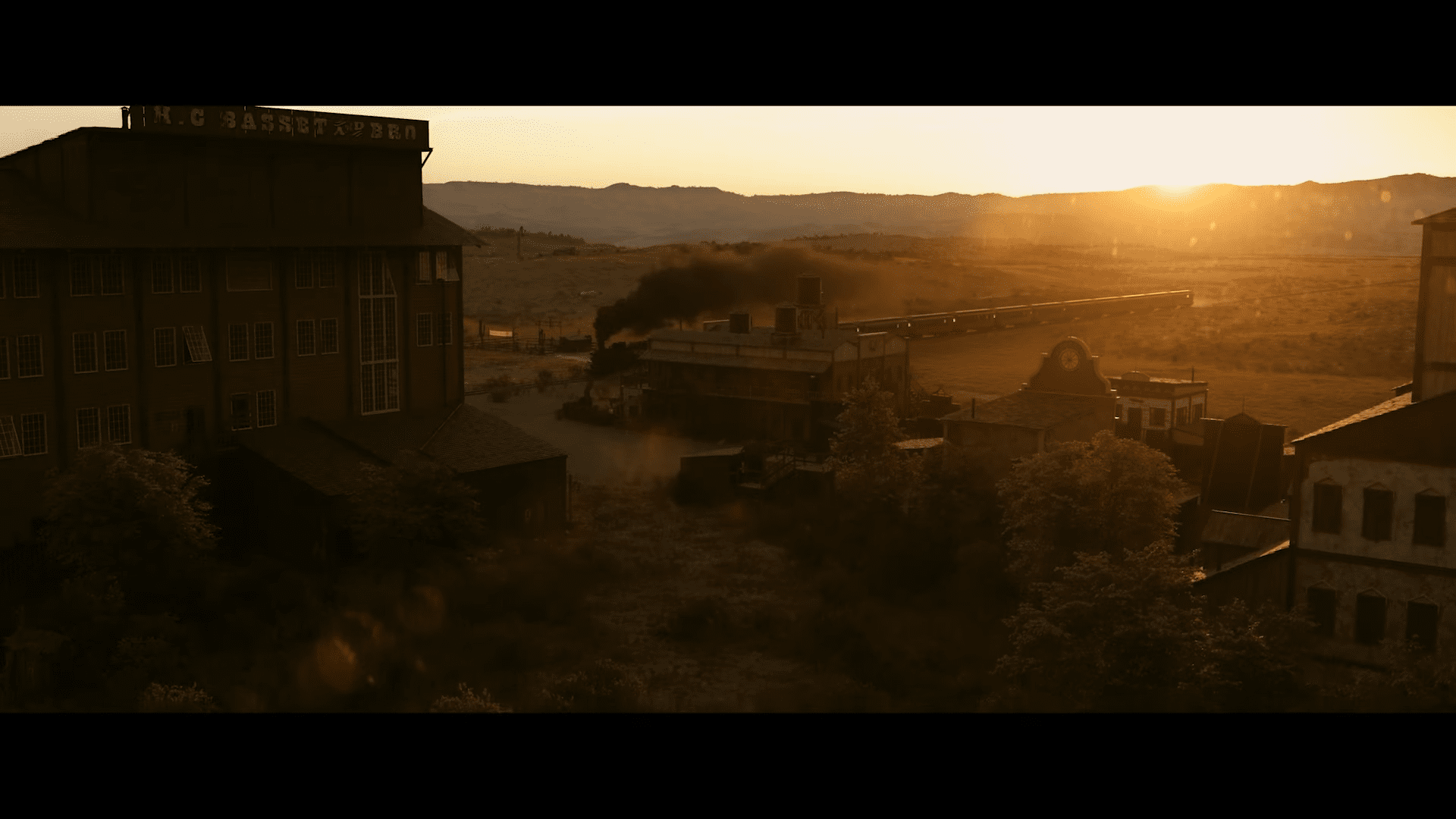

The transition from virtual production to visual effects to post-production should be as seamless as possible. That’s one thing that we feel that we support very well. The best example of that is the asset we used for the short film we created to announce Arena, Ray Tracing FTW. You can watch it here in full:

That was just one massive asset that had the entire town. That included the interior of the bank, five kilometers of train tracks, the tunnel, the bridge, every blade of grass… everything. In total, the asset contained around 2.8 trillion triangles, and the whole asset was generated in a matter of days. We used it for everything, then we’d take that same asset and use it for post-production, because we still had all the detail that we originally had from the beginning. That’s how you save a lot of money. So basically, why build it three times when you can build it once?

DP: You tested Arena extensively on the short film Ray Tracing FTW. What were some surprises?

Chris Nichols: Our assistant director on Ray Tracing FTW was Ben Hansford, a well-established commercial director that has experience with virtual production. He told us to plan for an hour to an hour and a half of crashes every day, because that’s what’s expected when traditionally working with virtual production. We ended up completing the shoot in three days without a single crash.

In fact, I don’t know of any crashes that have ever happened on set with Arena, at least nothing that was not recoverable in a matter of a few minutes. We didn’t expect it to be as stable as it was, especially in those early days when it was barely a product and the shoot partly meant to be a test for it.

DP: Real-time changes on set are often the stress test for virtual production. How did Arena and Vantage handle that during Ray Tracing FTW?

Chris Nichols: We aren’t doing any baking or anything like that, so real-time changes are trivial to us. That’s exactly the way it should be. Rasterized rendering can look very photoreal, but you have to do a lot to make it look like that, and some of the things you have to do to make it look photoreal involve not being able to edit it later. For us, if you’re just ray tracing the whole time, none of those things matter.

DP: Vantage has always been about pure ray tracing in real time. How does Arena extend that, and what does the combination unlock that wasn’t possible before?

Chris Nichols: When you’re done ray tracing, you’re done. You don’t have to solve any of the other problems, so you massively simplify your process. If you go back to 2006 when VFX started to adapt full ray tracing – not just the hybrid ray tracing that most game engines use – teams were still trying to rasterize things, but they started to realize they could simplify the process. They didn’t need to have things like full teams of shader writers, instead they could use ray tracing and that essentially solved the problem. It made things much, much faster and more efficient.

The same philosophy is true here when we’re doing real-time ray tracing. It gives us a big advantage, and it’s not just in the quality of how things look, it’s how fast you can make something look good, and how easy it is to get there. So you’re actually saving a ton of money by ray tracing.

In terms of what new technology has made all of this possible, when the 2080 graphics cards came out in 2018, it was the first time ray tracing cores were enabled on NVIDIA cards, and that let us design around that technology. But we weren’t able to achieve that super high level of quality resolution needed for virtual production until DLSS 3.5 came out. More recently, AI has made a lot of things possible. The best way to think about it is one out of every eight pixels is real, the rest are AI generated.

DP: For artists who are used to Unreal Engine or Unity, what’s the biggest mental shift when moving into an Arena/Vantage-based workflow?

Chris Nichols: Unreal and Unity are fantastic tools for making games, and essentially what they’ve done for virtual production is to try to gamify the film making process. Game engines turn everything into a game control system, which can work to some extent, but it completely deviates from the other systems that the movie industry has been using for a long time, especially visual effects. What we’re doing is we’re making it easier to streamline that process across all departments.

For people that have been using game engines, Arena is much simpler and you’re not sacrificing anything to get there. There are a lot of tricks and processes that you need to know for a game engine, and that’s just the way it has been. With Arena, we’ve had people ask if we can recreate a unique process they’ve been doing, but we don’t need to implement their workarounds. So their very clever tricks are completely unnecessary in the way that we do things.

DP: Gaussian Splats are hot right now. How do they behave inside Arena and Vantage compared to the hype we see in research papers?

Chris Nichols: Gaussian splats seem like they are here to stay, plus they are simple enough that it was relatively easy to support them compared to other standards in the past. The technology is also fairly familiar, and builds on the older light field technology that we experimented with years ago, first with companies like Lytro, then Google. Gaussian splats are essentially a representation of color and light from multiple different angles that change based on the angle you are viewing it, which is similar to what a light field does.

The problem with light fields is that it involves massive amounts of data, and lots of redundancy to get it there. So much so that they were impractical to use. But if you use neural fields to represent all the redundancy, it changes things. That’s basically what neural radiance fields, or NeRFs do, they are essentially light fields with a neural network. It’s a really cool system, but still very cumbersome.

So when gaussian splats came along, it solved a lot of issues. All we really need is a point in space and a shape on that point – typically a disc or an ellipsoid – that changes colors depending on the viewing angle. It’s such a simple idea that began as a concept and grew from there. And because they’re so lightweight, because they do so well, it just became so easy for us.

The benefit that we get from gaussian splats, and the way that we’re approaching it by actually ray tracing it – as opposed to rasterizing it – is that we can put 3D objects inside of a gaussian splat and they will ray trace that gaussian splat directly. The best example I can give is that you can take a gaussian splat of a city, and then you put a CG car on a street within the city. Then when the car travels through the city it will accurately reflect the environment within the gaussian spalt. If you did it as an HDR, every light point is at infinity, and that’s not how it really should be.

DP: From a director’s or DoP’s point of view, what kind of creative control does this system provide on set?

Chris Nichols: Everything that a DP would do manually, we can offer virtually. You can move lights, you can change colors, you can do all kinds of things. You can manipulate all of those different areas as well. We’re actually in the process of working on getting a DMX control for what we’re doing, so the digital gaffers can work together in terms of all the lighting controls you would have.

Another thing that we’re working on for the future is a new way of doing depth of field so that we can control the ability to figure out the distance between the camera and the wall, and add the appropriate compensated depth of field postwall. When the camera and wall defocuses are combined, it is the correct level that you would need for your set.

DP: Are there particular hardware setups that Arena and Vantage thrive on, or can it scale from laptops to full LED stages?

Chris Nichols: Most LED stages I’ve worked on have, at a minimum, an A6000 card, if not two, and that’s perfectly reasonable for most setups. That’s one of the practical advantages of Arena – it can be installed on an existing LED wall in a matter of a few hours, without changing any hardware. In fact, we do that all the time.

Another benefit of using this type of setup is that Chaos Vantage is a standalone app that can be installed on any laptop running an NVIDIA card. So a virtual production supervisor, a VFX supervisor, or even a director can open the scene and look through the 3D environment on their laptop.

DP: What role does MaterialX play in enabling consistency across tools, especially when moving assets between DCCs and Arena?

Chris Nichols: When someone uses Arena, they may work on an asset that ends up going to several different visual effects studios, each of which has their own pipeline and tools. Some might be using V-Ray, some might use Mantra, some might be using Arnold, and on and on. We want to make sure all of those studios can continue to use the same asset without any compatibility issues. And for shaders to translate, the best thing we can do is support MaterialX. As long as a studio supports MaterialX, they can use the same asset as everyone else without issue.

DP: If you look at the ideal future workflow, what would be the hand-off between on-set capture with Arena and finishing in post with Vantage or other Chaos tools?

Chris Nichols: Really, it’s just a matter of being able to use the same asset. You can have an asset at a post-production house, then hand it off to a virtual production studio and keep doing what you’re doing. The asset might receive some changes along the way, but when you get it back, it’s essentially the same asset.

When we were working on Ray Tracing FTW, there’s a scene in a Spanish hacienda. We were busy getting everything ready, so we didn’t have time to build one ourselves. We just went to Evermotion and bought one for around $100, and within 10 minutes it was on screen. It just worked. There are a ton of great assets out there that are Arena ready, and you can find comprehensive libraries filled with virtual production-ready assets from sites like Turbosquid, Evermotion, and KitBash3D to name a few. Hopefully, future workflows will keep things easy. We’re not trying to overcomplicate things. Just use one asset and use it across everything.

DP: Finally, what’s next for Chaos Labs in this space?

Chris Nichols: With Chaos Labs, each project builds on the success of the last, and each new experiment opens the door for the next. For our film Ray Tracing FTW, we wanted to know if Arena could work as a virtual production tool, and it did, because we could see how easy it was to go from one asset to the next. Right now, we’re building on that and testing to see how we can improve the complete filmmaking workflow, from the earliest stages of development to the final pixel, all using a single asset that will be developed throughout the lifecycle of a film.

One of our focuses with Chaos Labs right now is on creating a previs system for Vantage that enables camera tracking on a bluescreen environment. Using the same asset for previs, we can then translate it for virtual production for in-camera VFX, and then go on to be used for final production. So we’re really looking at the full lifecycle.

DP: What would be your recommendations for people getting into it?

Chris Nichols: Arena is designed to be easy. It’s virtual production made simple. You don’t need to learn any complicated new techniques or workarounds, you just use what you already know. Your pipeline, your choice. Load the free trial and give it a whirl!

DP: What good resources are out there to learn more about it?

Chris Nichols: There’s a lot of great documentation out there. We make it a point to offer as many tips and documents as possible. There are also tutorials and things like CG Garage. I recently recorded an episode specifically about this.

DP: What is the next project you are working on ?

Chris Nichols: There is a feature film in development that we are using as a major case study for Chaos Labs, designed to showcase how this can all work. We feel strongly that Arena and Vantage will debunk the idea that virtual production is only for big, expensive movies. It’s a tool that can be used for everything, even low budget independent films. They can have the same power and process as a major production, at a much lower cost. That’s what we’re trying to do within Chaos Labs. We want to show people that you can do your $5 million movie with virtual production and get the same results as films with huge budgets.

- Editorial Comment: Did Chaos Lab want their name in every sentence? No. But we find it funny to have a highly technical topic, talking to a top-shelf expert, and almost every sentence has the word “Chaos” in it? Yes, because I am somehow still cursed with the humor of a 5-year-old. ↩︎