How was your 2012? Good? With small gaps? The holes in the schedule were originally reserved for “Bioshock Infinite”, which was unexpectedly delayed. At the final launch, the DP didn’t miss the opportunity to find out why it all took so long, what changed and what the process was like. After speaking to producer Ken Levine last year, this time we asked Bill Gardner, Design Director and User Experience Specialist at Irrational Games.

Bill Gardner, who studied at the renowned Boston Film School and then worked at Universal Studios, has had the classic dream career of a game developer: first working at GameStop, meeting Ken Levine there by chance and then joining one of the most creative studios, Irrational Games.

He started with the Unreal Editor, then worked his way up from QA to Assistant Producer. As a User Experience Specialist, he is practically the first player to provide the feedback loop to production. As he doesn’t directly programme, model or texture the game himself in this role, he is the one who decides what gets thrown out – something that is part of the corporate culture at Irrational Games.

DP: Mr Gardner, what have you actually been doing over the past year? “Bioshock Infinite” was as good as finished, wasn’t it?

Bill Gardner: Apart from the underlying story – the player between two extremist, fanatical parties – we touched everything at least once more. We completely rebuilt a lot of things, both technically and in terms of gameplay and aesthetics. One of the most important changes was the realisation of Elizabeth, the player’s counterpart. You rescue her from a sticky situation and play the rest of the game with her. The character continues to develop. At the beginning, we perhaps underestimated how much work it takes to make the character believable, realistic and likeable. Both in terms of the gameplay and the story.

DP: In the first hands-on of the beta version, we noticed that you included the religious right of the USA as one of the enemies in the game. How violent could the resulting storm of outrage be?

Bill Gardner: We have two factions in the game: The “Founders” (alluding to the mythology of the creation of the United States) are led by the inventor of the flying city of Columbia. He appears to be a prophet, predicting certain events. However, Columbia breaks away from society and disappears completely from the scene for a few years. When the player enters the city, society there is divided, roughly comparable to the suffragette movement that spread across America at the turn of the century. The counterpart to the “Founders” – called the “Vox Populi”, a labour movement – picks up momentum and develops into extremists to the same extent as the “Founders”.

This conflict is caused by the player: He is the catalyst that escalates the situation by freeing Elizabeth. It remains to be seen how these obvious allusions and categories will be received by the public.

DP: Within the game, you often come across various propaganda scenes that were also shown in the trailers. Were these specially produced or were they created from the graphics and assets of the game engine?

Bill Gardner: The former – even if we had to create some of our own scenes within the engine as a stage for the propaganda. Capturing the in-game assets as a film, with titles and post-production was a lot of fun and a different approach to the visual language. The propaganda films of the period around 1900 were something special in many respects: short film segments with an extreme message that was also conveyed directly: “This is good, this is evil. Evil is evil because we say so. If you do something evil, you’re an evil person. The End.” You rarely have the opportunity to design something like that in games. It’s a great pleasure to produce something like that.

DP: How much research and reference to the period and its view of the previous era, the 17th and 18th centuries, was necessary to set the tone of the first “nostalgia wave”?

Bill Gardner: We collected an almost unmanageable amount of material – also in order to be able to depict the overall culture of the time, with its allusions and absurdities. Within the game, our aim was to show a 21st century player the mindset of the time. At the same time, we wanted to give people who were already familiar with the era enough overt or hidden references and clues to make it feel culturally real and not like a wild fantasy. In addition, some of my colleagues – including Ken Levine – are amateur historians and are interested in such topics. They have infected almost everyone with their enthusiasm for the subject.

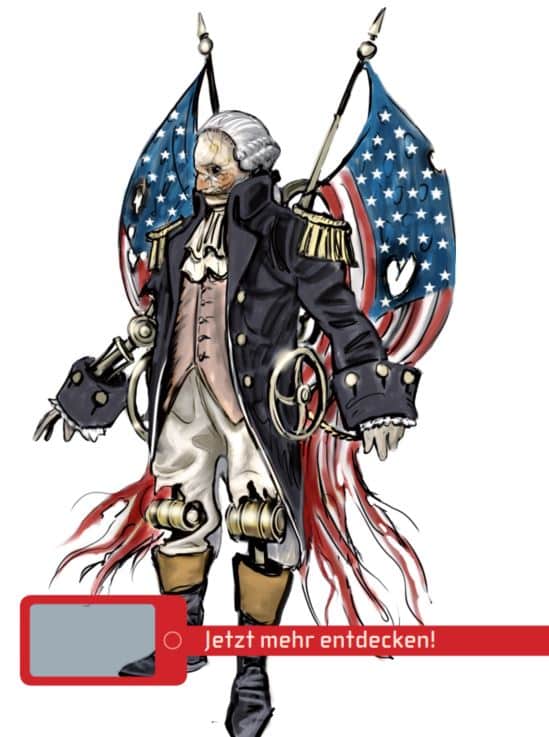

DP: But equipping a boss as a machine gun android with the face of George Washington is something you don’t find in normal American imagery ..

Bill Gardner: The Motorised Patriot comes from the fact that we wanted a robot-like character that moves through the city. And then one day a colleague arrived with mannequin faces, which were used for the funfair machines at the time. Combine that with the cracks in the porcelain and the broken corners on the mask? On a three metre tall robot? With the face of George Washington barking propaganda and attacking with a Gatling gun? We couldn’t pass up an opponent like that. That’s what makes a Bioshock game: with an accurate “look and feel” of the time, there’s also room for enemies and characters that work really well in the context of the story.

DP: Given that the game is now not a completely open-world game, how much did the underlying engine need to be adapted to meet the design requirements?

Bill Gardner: Especially at the beginning of the game, there is a lot of information for the player: Story, items and general controls. That’s why we took the player more by the hand at this point than in the rest of the game. For example, we haven’t included a classic tutorial, instead the player walks through a fairground with stalls and gets to know the various weapons and special powers. Later on in the game, the paths become more open and players have to find their own way. So it’s not a real open-world game, but rather different arenas in which the player moves around. By building the flying city of Columbia, however, we were able to develop each area, or rather each flying island, individually. These islands as well as zeppelins, ships and so on move independently and in relation to each other. They orbit each other, dock and much more.

DP: That’s certainly not easy for the development of the game, is it?

Bill Gardner: Indeed. Apart from the cut scenes, you can’t get people to look up in a shooter. But with this moving backdrop, we’ve built a shooter that doesn’t feel like a linear experience, but much more open and free. But it was also a real challenge for the design department: how far can you let the player jump from rooftops, or how long can they run along the floor of the island? How vertical can a game become before it becomes confusing? The additional dimension increases the technical challenge in terms of streaks and loading speed enormously.

DP: How many assets had to be created due to this verticality and the custom design?

Bill Gardner: Too many (laughs). It feels like we’ve gathered enough assets for another three games. There are countless details, especially when it comes to the interior, i.e. the furnishings of the bars and living rooms as well as the everyday objects. In one of the bars, for example, we modelled and integrated all the drinks with their respective bottles and their special shape. Thank goodness we were able to generate or procedurally create most of the buildings and architecture – including window placement and the like. If we hadn’t pulled ourselves together with the size of the world, the story and the development of the main characters would have been neglected. Long story short: I don’t know exactly. There were rumours in the studio that one level in “Bioshock Infinite” was as big as the entire first Bioshock part in terms of assets and dialogue.

DP: Has Irrational considered releasing the FloatingIsland technology as software or an SDK?

Bill Gardner: No, we’re not going to do that. The whole process is so closely linked to the engine and assets that it wouldn’t be practical. We have linked the underlying Unreal Engine 3 with self-built lighting, physics and simulation, a completely new artificial intelligence and the Kynapse middleware in such a way that the end result is quite a “Frankenstein” (laughs). Everything docks somewhere, and individual parts can hardly be detached without fundamentally restricting their function. But when I see our customers, they would certainly do great things with it.

DP: Since you mentioned Kynapse: What software do you use? 3ds Max, ZBrush or something else?

Bill Gardner: That’s not easy to answer either. In Kynapse, we had to develop some special features so that the artificial intelligence could also handle the skyline, i.e. the connections between the buildings, and the verticality. As the characters can jump off at any time, expanding the existing intelligence was not without its challenges. The programmers, designers and gameplay people worked closely together, including with nightly builds for Kynapse and tests.

DP: The lighting turned out great, switching effortlessly between the mood of a relaxed stroll and the menacing grotto. How did you achieve this and how much attention was paid to the design?

Bill Gardner: We put a lot of effort into it. It was an intense collaboration between production, art department, level designers and the tech guys. One of the best techniques we use is Beast from Autodesk. We did a lot with light colour, mood and quantity in the various iterations. The closer you get to the “Vox Populi” or even in some threatening scenes, we controlled it at the beginning just by that. The surface, the idealised America at the turn of the century, was also created a lot with this lighting design.

DP: You also worked a lot with natural light.

Bill Gardner: Yes, that’s right. We also simulated times of day this time. So you regularly see the golden hour with its warm orange light. Then the story forces you into buildings at night, where the lighting design is similar to the underwater city of Rapture from the first Bioshock instalment. This allows you to create a certain, natural game rhythm that every player immediately recognises and understands – and in which deviations from logical behaviour naturally work particularly well, such as when you are in a dark hall during the day. When the harsh light shines through the window, a film-noir atmosphere is palpable.

DP: To what extent do you control the player’s emotions in this way?

Bill Gardner: I think you can convey an enormous amount of emotion through the lighting design. The art department also did a great job in this area in the scenes with Elizabeth.

One of my favourite scenes was the E3 demo we released a while back. Here, Elizabeth is kidnapped by a Songbird – a mechanical bird – and dragged out of the player’s reach in slow motion. In this scene, both the menace and the panic are beautifully resolved by the light focussing first on Elizabeth, then on her face and finally on a single tear. This is something that, in my opinion, is neglected in many games: Uniform lighting does not focus the player’s attention on the essential points of the respective game world.

DP: The lighting mood and its perception depends heavily on the player’s hardware. What do you test on and what do you think are the most commonly used setups for playing “Bioshock”?

Bill Gardner: I usually do it on a calibrated monitor in a dark room. I don’t have exact numbers for the players outside, just experience. We test so that the player can use as many variants as possible. The spectrum ranges from a bright living room with a small CRT screen to a dark basement with the contrast turned all the way up. The aim is to cover as many extremes as possible. Of course, you have to set yourself limits. I think a game still has to be playable on a screen three metres away with the sun behind it – that’s a real setup that we also test. But the majority of the customisation for extreme hardware – particularly large or small, for example – we intercept with the options menu. This must allow fine adjustments. We have developed our own benchmark tool for this, which can be used to determine the ideal hardware settings.

DP: Will a supplied monitor profile become the standard for graphically complex games at some point? Or are many gamers not interested in this?

Bill Gardner: We would definitely do this if gamers wanted it. But certainly not right from the start. It’s interesting to see that when a game is released, some gamers discover niches – for example, the “perfect colours”. These niches are exciting because you haven’t seen them before.

DP: Keyword jobs: What do you want from developers? Does the résumé have to be peppered with glamorous triple-A titles?

Bill Gardner: You can ask 100 developers that question and you’ll get 105 different answers. I can only speak for Irrational and we are a story-driven studio. For a level designer, it’s important that the story is developed within the demonstration and not an empty labyrinth. What matters is how the tools are used for the story, not whether you’ve helped develop three dozen indie games or been involved in five triple-A titles. DP: What do you notice when applications land on your desk? Bill Gardner: Many try to score points with a mountain of content and provide a demonstration of every development step. But it would be better to concentrate on a few skills and perfect them. Then there are the people who want to show that they have mastered one thing perfectly, i.e. quality vs. quantity. On the other hand, it has to be said that the tools and programmes are becoming easier and easier to use. In general, the field of game development almost has a glamour factor. Accordingly, there are a lot of applications, especially from the big studios. That’s why I believe that something that you can see the care and personality of the designer in is always better than just trying to fulfil the standards.

DP: Can one person still cover all the steps of a production – especially for a triple-A title? Is it even possible – even with an SDK – to get started independently without specialising from the outset?

Bill Gardner: I have mainly gained experience with the Unreal Engine. I have to say that all SDKs released by engine developers are now being used excellently. And even with assets the size of “Bioshock”, the individual can still keep an overview. Of course, it is anything but easy, but it is possible in principle.