Table of Contents Show

Shaders and bitmaps – textures in two forms

In the last part of our series, we looked at methods for smoothing geometric facets. The work of Henri Gouraud (1971) and Bui Tong Phong (1975) are central to this. Phong shading in particular aims to smooth the surface behaviour of an object with a limited number of polygons in such a way that the impression of a smooth surface with flawless reflections is created. Diffuse and specular reflections therefore appear as if an infinite number of polygons are involved.

If you like, Phong shading, the Phong lighting model and all BRDFs based on it basically add a level of detail that is not given by the pure number of polygons. This is particularly noticeable in BRDFs such as Cook-Torrance or Oren-Nayar, which are based on microscopically small surface irregularities without these actually being present as polygons.

Textures follow a similarly enhancing approach: as a coating for 3D models, they increase the visual level of detail of an object without increasing the level of detail of the geometry. For example, a carbon fibre component does not have to be modelled from countless microscopically fine carbon fibres, but the corresponding texture creates this level of detail (Figure 1). There are two different approaches for the application of textures – shaders and bitmaps.

- Shaders – rule-based patterns: Shaders are small programmes within 3D software or a game engine that specify surface properties according to certain mathematical rules. In C4D, a slightly turbulent colour gradient shader can create the effect of slight damage on the edges of a window sill, for example (image 2). However, shaders can not only imitate natural surfaces, they can also react interactively: For example, the ambient occlusion shader creates a darkening depending on the object approaches.

Image 2: Shader in use: On the lower edge of the window sill, a slightly turbulent colour gradient simulates the effect of slight edge damage. On the tabletop, a subtle ambient occlusion shader creates diffuse shading as it approaches the tea lights. On the glass of the candles, total internal reflection and emitted reflection create the typical double reflections, and a subsurface scattering shader in the luminaire channel of the wax ensures light scattering below the surface

- Bitmaps – photo wallpapers: In addition to shaders, bitmaps, i.e. pixel images such as .tiff or .jpg, can also be used as textures. These images are applied to the object in question like a photo wallpaper using certain projection methods. In contrast to shaders, bitmap textures are easy to calculate and generate a high level of realism in themselves, although this comes at the cost of a lack of flexibility and limited bitmap resolution.

In the everyday work of a 3D artist, it is usually combinations of shaders and bitmap textures that are used for an object or a scene. A strict either-or is usually not up for discussion, as both texturing methods have their advantages and disadvantages. Let’s take a look at two examples: On the table top in the interior close-up shown

(Figure 3), a bitmap texture defines the diffuse reflection (albedo) of the tabletop, while shaders ensure a light-dependent appearance of ambient occlusion in the vicinity of the objects and a viewing angle-dependent strength of the specular reflection. The Earth view in the cover image, on the other hand, makes heavy use of high-resolution bitmap textures from NASA to define diffuse reflection and silhouettes of land masses. Shaders are used in the image to create the atmosphere and geological layers.

Material manager control centre

For an introduction to the C4D material system, we will first look at the control centre for creating and assigning materials: the material manager. Important functions can be found in the Material Manager menu: “Create” allows you to create a new material, as does the Ctrl N shortcut. However, the menu item offers further options such as the creation of a physical material (more on this later) or a special shader (hair, architectural grass, pyrocluster or the somewhat outdated BhodiNut shader). The menu item “Edit” offers some options for organising and displaying the materials, and “Edit” provides important functions such as removing unused or duplicate materials.

Image 4: The hub for material management:

Image 4: The hub for material management:the material manager

Materials are displayed in the material manager as freely nameable icons. Materials are then assigned to specific objects in C4D using drag-and-drop: The material icon in the material manager is simply dragged onto the desired object in the object manager. It is then created there as a texture tag next to the object. The material can also be assigned by dragging and dropping it onto the object in the viewport.

Right-clicking on the material icon in the material manager offers interesting options such as selecting the associated object in the object manager (“Texture tags / Select objects” command) or selecting the material icons of currently active objects (“Select materials of active objects” command). Double-clicking on the material icon opens the

Material editor, which then offers the actual option of editing the material.

Channelling material properties

The channel-based nature of C4D materials becomes apparent in the C4D material editor. The term “channel” is basically just a synonym for a certain aspect of a material (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Control centres side by side: material editor, texture tag in the object manager and its parameters in the attribute manager. In the material editor, the expanded colour selector in “Colour wheel” mode offers numerous options for creating colour harmonies. Details on texture projection can be found in the corresponding drop-down menu of the texture tag

Colour

The colour channel defines the diffuse reflection of the material with a colour selector, a brightness control for blending with black and the option of loading and blending bitmap textures or shaders. This basic configuration is common to all colour-relevant channels of a material. The colour channel also has a drop-down menu for lighting models (“Lambert” or “Oren-Nayar”, see part 1 of the article series). The colour channel fulfils an essential task of a texture: it basically says: “Show me where I am in the light”.

Since R18, the colour picker mentioned above has been a powerful tool for systematically creating, analysing and changing colours. It has three different modes:

Colour circle: Here, colours are arranged in a circle around a centre point and can be varied in a separate brightness scale. The plus and minus buttons can be used to create sample points in the colour circle and move them freely. Above the colour circle there are buttons for creating different colour harmonies according to the artistic discipline of colour theory. Generated sample points are brought into certain relations to each other by these buttons in order to match the selected colour harmony

Colour harmony – e.g. “complementary”, “tetrad” or “equiangular” (Fig. 5).

In the colour spectrum, colours are arranged as a linear spectrum and can be varied according to brightness and saturation in the field to the left.

With colour-from-image, colours can be taken from a loaded reference image. Here too, sample points can be created and freely moved using the plus and minus buttons.

The “Average” drop-down field offers the choice between pixel-precise or average-based colour determination. Clicking on the small mosaic symbol calls up the “Detail” control field, which can be used to create a coarsening of the image that reflects the average colour of an image area.

In all three modes, you can choose between different colour spaces, namely RGB, HSV and a Kelvin scale extended by a colouring function (“T” for “Tint”). In addition to these three options, there is also a colour mixer for creating a colour from two mixing sources, a colour field system for organising and saving colour fields and a colour pipette for colour samples from the entire desktop.

The extensive options of the colour selector can be visually reduced and made clearer using the “Compact” mode. This mode can be found as a button directly under the “Colour” field and can be defined as the default in the program settings (“Units”).

Diffusion

The task of this channel is to darken surfaces. Greyscale information from bitmap textures or shaders is evaluated in order to attenuate the glow channel, highlight or reflection in addition to the colour channel. The term “difussion” is therefore rather misleading. The most common use of the diffusion channel is the use of the ambient occlusion shader or smart modifications of it (see Figure 3).

Luminaires

The luminaire channel defines self-illumination in the sense of ambient, lighting-independent illumination. In terms of the Phong lighting model, it would be responsible for the ambient component(see last part of the article series). A frequent use of the luminaire channel is the use of the subsurface scattering shader (Figure 2). In combination with Global Illumination, the luminaire channel can also generate actual light.

Transparency

This channel is responsible for the transparency and refraction of transparent materials. If bitmap textures or shaders are loaded, they vary the transparency according to colour and brightness. The channel tracks a number of important parameters: Refraction defines the refractive index (IOR, Index of Refraction) of the material (e.g. water 1.33). Fresnel reflection creates a reflection dependent on the viewing angle (yes, you read that right – in the transparency channel!). The “total internal reflection” produces a reflection in the direction of the surface normal, while “exit reflection” produces a reflection in the opposite direction to the surface normal. These two reflections can be used, for example, to generate the double reflections of glass vessels (see Fig. 2). However, switching off the exit reflection can produce a somewhat tidier appearance and also save computing time. Absorption colour and distance determine over what distance the light is absorbed and in what colour – ideal for creating coloured liquids – and last but not least, the matt effect defines whether and to what extent the transparency is scattered, e.g. for frosted glass. The process is sample-based, so it can affect the rendering time.

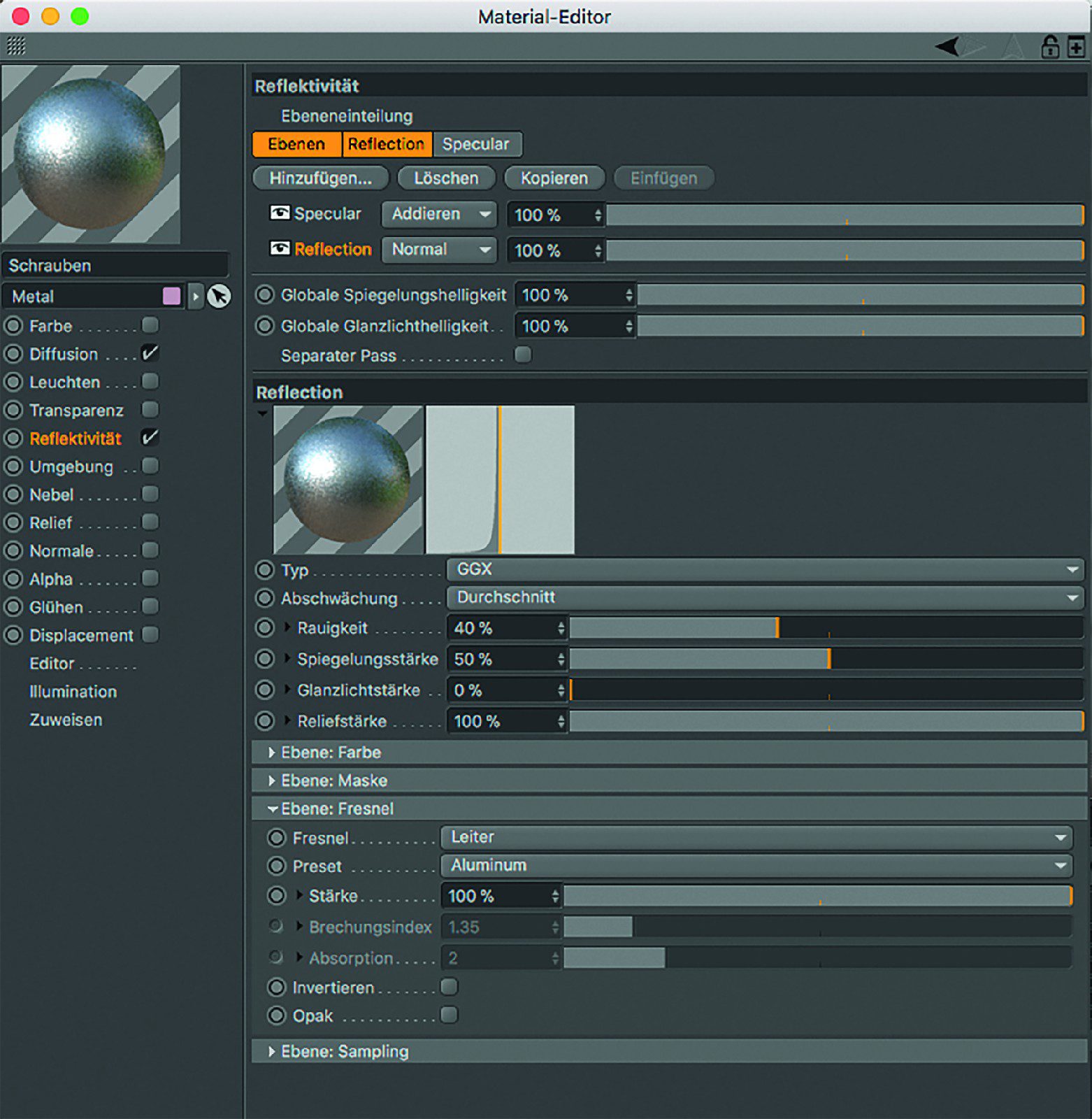

Reflectivity

The reflectivity channel in C4D accommodates all reflective aspects of a material in the form of various reflectivity models. These can be stacked as layers in a photo

these can be stacked on top of each other as layers in photo-shop style, offset against each other and mixed. You can choose from a range of different reflectivity models. These are basically BRDFs in which (with two exceptions) only the specular reflective aspects are analysed.

In doing so, we again encounter the names of old acquaintances: BRDFs for sharp or scattered specular reflections are, for example

Beckmann, GGX, Phong or Ward. The reflectivity models that are capable of generating a true specular reflection (Beckmann, GGX, Ward, anisotropy) also have their own specular component so that specular and specular reflection can be controlled separately for each model. Here is an overview of the most important models:

- Beckmann as a preset standard model is suitable for most applications such as plastic, water surfaces, glass etc. With pronounced reflective roughness, the curve diagram shows a rather abrupt end in the decrease curve. The Ward model is very similar, but produces somewhat duller reflective surfaces with higher roughness.

- GGX, on the other hand, is characterised by a significantly broader, softer acceptance behaviour of scattered (rough) reflections. It is therefore ideal for metals with pronounced diffuse reflections (Fig. 6).

- Anisotropy is suitable for the visualisation of anisotropic materials (i.e. materials whose reflections are disproportionately stretched). It should be noted that anisotropy is only effective if the reflection has been given a certain degree of roughness. Good starting values here are e.g. 20% roughness.

- Irawan is the go-to model for woven fabrics. The anisotropic reflection of woven textiles can only be created really credibly with this model. Various presets (silk, jeans, etc.) make it easy to use (Fig. 7).

- Blinn (old) or Phong (old) are available for creating pure glossy reflections, which are still not physically correct, but are wonderfully visually customisable(see part 1 of this article series).

Image 7: The reflection model Irawan in use for the fabric of the couch: An anisotropic reflection behaviour in combination with presets for weaving patterns of various kinds make Irawan the go-to model for fabric reflections.

Image 7: The reflection model Irawan in use for the fabric of the couch: An anisotropic reflection behaviour in combination with presets for weaving patterns of various kinds make Irawan the go-to model for fabric reflections.- Lambert (diffuse) and Oren-Nayar (diffuse) are an exception in the reflectivity channel, as their BRDFs are analysed exclusively in terms of diffuse reflectance. As their reflection has a 100 per cent roughness, there is no longer any dependence on the viewing angle – the specular reflection has thus become a diffuse reflection. In this way, the reflection basically behaves like the colour channel, which is there to reflect light completely diffusely.

- With Lambert (diffuse) or Oren-Nayar (diffuse), we can actually switch off the colour channel, as we already generate a diffuse reflection with this model – and physically correct, because the diffuse reflection is thrown back and forth between objects like a normal reflection and generates indirect light and colour bleeding – by definition a kind of global illumination. The brute force GI generated in this way is only limited by the “Depth of reflection” parameter in the render preset options and has no accelerating calculation methods such as radiosity maps or light maps. It is therefore significantly slower than the global illumination of the standard or physical renderer. However, as all reflective aspects of such a material are handled under the umbrella of the reflectivity channel, it forms the basis for PBR: Physically Based Rendering.

- Attenuation modes: All reflectivity models have a so-called attenuation mode. Its drop-down menu is located directly below the selected reflection model and describes nothing other than the way in which reflections or highlights are offset against the colour from the colour channel of the material. In practice, only two models actually count. “Average” treats the reflection in a similar way to the Photoshop

Normal” layer mode: The reflection has an opaque effect and completely overwrites the colour channel at 100% opacity so that no more colour is visible. This mode is ideal for metals as they only have a specular and not a diffuse reflection (image 8).

The colour channel can therefore be safely switched off in this case. And “Additive” handles the reflection in a similar way to Photoshop’s “Additive” layer mode: only the bright areas of the surroundings are reflected. “Additive” is ideal for clear varnish on cars, painted wood, plastics, water, glass, etc. The difference to “Average” is particularly clear with light-coloured objects, as the content of the colour channel is not covered by the reflection. “Additive” is therefore the most common mode. - Numerous detailed settings: Each reflectivity layer also has the option of defining Fresnel reductions. For example, presets of dielectric or conductive materials can be used via the “Layer: Fresnel” area. This also includes presets for metals, whose coloured reflection is created by a spectrally different Fresnel attenuation(see part 1 of this article series). Furthermore, each reflectivity layer has options for loading shaders and bitmaps for masks, colouring and parameter changes. For example, the value of the specular scattering (“roughness”) can be varied with a noise shader (Figure 3).

There are also plane-specific settings for taking the relief or normal channel into account or for loading your own relief or normal maps.

Environment: This channel simulates the reflection of an environment by using a spherical image or shader environment without a real reflection taking place. The cars in the Cinebench R15 OpenGL test scene I created make heavy use of this(maxon.net/en/products/cinebench/).

Fog: Creates a fog effect in closed bodies, whereby the colour and distance of the fog can be defined. The fog channel also takes into account the IOR of the transparency channel.

Relief: The relief channel simulates the deflection of the surface normal by greyscale information of a bitmap or a shader. This simulates a surface deformation, but the geometry itself remains smooth and flat. The “Parallax” parameter further enhances the relief effect by adding a perspective offset and making relief elevations visible from the side, so to speak.

Normal: Similar to the relief channel, a surface deformation is also simulated here using bitmap textures or shaders. However, instead of using only one grey scale value (as in the relief channel), three RGB values are evaluated in order to simulate more defined and better

To simulate more defined and better unevenness (Fig. 8).

Image 8: The floor and ceiling of this underground station from the film “Unter freiem Himmel” (bit.ly/ufh_teaser) show regular structures through the use of normal mapping. A SAT mapping and a blur strength of 3O% interpolate the details towards the horizon so elegantly that no artefacts or flickering occur with a moving camera

Alpha: This channel determines punched-out areas of objects based on the grey levels of bitmaps or shaders. Bitmaps with a real alpha channel (e.g. .tiff) that is automatically recognised with the “Alpha image” checkbox are recommended for use. In contrast to the transparency channel, no optical refraction is generated. Alpha maps are the ideal way to stack textures. In the illustration of the underground escalator, for example, another texture with an alpha channel – a graffiti bitmap – has been dragged onto the metal texture of the escalator wall. The following applies here: The right-hand texture tag lies “on” the texture tag to the left of it (Fig. 9).

Image 9: Alpha maps and texture stacking: The graffiti on the side of the escalator and the red warning sign on the right are typical examples of the use of several texture tags on one and the same object.

Image 9: Alpha maps and texture stacking: The graffiti on the side of the escalator and the red warning sign on the right are typical examples of the use of several texture tags on one and the same object.Glow: This rather outdated material channel creates a glow effect around the object in question as a post-effect after rendering – a task for Photoshop or After Effects in a professional workflow. It can therefore be safely left switched off.

Displacement: The displacement channel creates a real surface unevenness based on the grey levels of bitmaps or shaders. However, this only becomes visible during rendering. The “Sub-polygon displacement” option provides a further subdivision of the geometry and finer details during rendering.

Editor: This channel defines the quality of the texture preview and playback options for video textures in the editor.

Illumination: Parameters for generating and receiving GI light through the material and for generating caustics are hidden here.

Assign: The Assign channel shows the objects to which the material has been assigned in a list. If an object is dragged into this list, the material is assigned to the object.

After this overview of Cinema 4D’s material channels, let’s look at some details about the two types of texture creation: Bitmaps and Shaders.

Soft rendering instead of flickering

In the material editor to the right of the word “Texture” you will find a button with a small white triangle on it. Clicking on this opens a menu which contains a number of useful functions at the top, such as “Copy shader / image” and “- paste” or loading and saving presets. The latter is particularly useful in connection with shader setups. Clicking on the small texture preview image, on the other hand, opens the shader dialogue. The “Shader” tab contains buttons for reloading the image, editing it in an image editing programme or locating the image file in the computer system.

The “Interpolation” drop-down menu underneath is interesting. When viewing a bitmap texture in perspective, there are countless texture pixels on one screen pixel. If no smart interpolation is carried out here, nasty moiré artefacts or flickering on the horizon occur when the camera is moving. High-quality texture interpolation is therefore mandatory – the photo wallpaper must therefore be ironed. There are several methods to choose from, only two of which are of practical relevance: MIP and SAT.

MIP mapping, “Multum in Parvo”, Latin for “many in one place”, is the preset standard method for pixel mapping and offers good texture smoothing with moderate and memory-saving computing effort. However, SAT mapping is more suitable for highly demanding texture smoothing.

SAT mapping (Summed Area Tables) offers an even better approximation and even more artefact-free texture smoothing, but this comes at the cost of higher memory requirements and a slightly longer rendering time. SAT mapping is therefore suitable for highly detailed ground textures up to sizes of 4000 x 4000 pixels – from then on, the system automatically switches to MIP mapping (Fig. 8). Procedural shaders always have SAT mapping.

In the “Basic” tab, the shader dialogue offers two further options if texture smoothing is still not sufficient:

Blur offset: This parameter can be used to soften the texture. However, you should proceed very discreetly here, as visible square artefacts will appear if the texture is blurred too much. This should not be confused with a Gaussian blur.

Blur strength: This often underestimated parameter can save your texture interpolation, as it increases the selected mapping (MIP or SAT) by a percentage. This was the only way to achieve flicker-free floor and ceiling structures in the illustration of the underground station (Fig. 8).

Videos as textures

The “Animation” tab of the shader dialogue makes it possible to even use image sequences or video files as textures. The “Mode” drop-down menu offers three options for the play direction (“Simple” for one-time complete playback, “Cyclic” for playback in a loop and “PingPong” for playback as a forward-backward loop).

In the “Timing” area, you can define whether the sequence is played to the frame or to the second, which area of the sequence is used or how often a loop is repeated. A click on the “Calculate” button captures the entire image sequence and even calculates its frame rate. By the way: If the image sequence is also to be animated in the editor, the “Animate preview” checkbox must be ticked in the “Editor” channel of the corresponding material.

Texture projection – applying the photo wallpaper

Now that we have a solid overview of the material manager, material editor, material channels, texture interpolation and shader dialogue, let’s take a look at the options for applying textures – whether bitmap or shader – to objects. We have already learnt how to assign materials by dragging and dropping them from the material manager onto the object and storing them as a texture tag. The texture tag itself offers a number of far-reaching options when clicked on, which are displayed in the attribute manager (Fig. 5). Here are the most important ones:

Selection: Existing selection tags can be dragged into this field. The texture then only affects this polygon selection.

The drop-down menu “Projection” is of central importance for applying the texture.

Projection: You can imagine this process to be like sticking up a photo wallpaper or projecting a slide through a projector. There are four geometric projection types, the names of which are self-explanatory: sphere, cylinder, surface and cuboid mapping.

These projection types also directly associate the shape of the objects for which they are ideally intended. For example, cuboid mapping is a logical choice for cuboid objects, while photos in picture frames are given surface mapping (Fig. 10).

Frontal mapping: Here, the texture is projected onto the object from the active camera’s point of view, whereby the size of the projected texture corresponds to the aspect ratio of the image in the render presets – ideal for remodelling photographed objects.

Image 1O: Different texture projections and their use: The photos in the picture frames are applied with surface mapping, while the texture of the table is applied with cuboid mapping. UVW mapping was used for the texture of the white chairs and their curved parts

Image 1O: Different texture projections and their use: The photos in the picture frames are applied with surface mapping, while the texture of the table is applied with cuboid mapping. UVW mapping was used for the texture of the white chairs and their curved partsSpat mapping: This type of projection is basically an enlarged surface mapping. However, the texture is shifted diagonally to the left with increasing object depth.

UVW mapping: We are already familiar with the three spatial axes X, Y and Z when working with 3D space. Points of a polygon object can be precisely recorded using these coordinates. In order to capture the points of a 2D texture exactly, a 2D coordinate system is required on this 3D object. And this is exactly what UVW coordinates are.

Why all this? As long as objects fit into the above-mentioned shape categories such as surface, sphere, etc. and do not have complicated geometry, the above-mentioned projection types are ideal. For more complicated geometry, further modelling steps or even deformation of the object, however, UVW mapping is unavoidable: it virtually nails the 2D coordinates of a texture to the 3D coordinates of an object – a property that the geometric projection types do not have (Fig. 10).

In addition to fixing texture coordinates, UVW mapping also offers the option of precisely assigning texture areas to an object surface. To do this, however, the UVW coordinate system must first be relaxed and unwound in Bodypaint 3D – an area that is beyond the scope of this series of articles.

By the way: Basic and spline objects (Lathe, Extrude, etc.) are automatically equipped with UVW coordinates. If these bodies are converted into polygon objects using “C”, a UVW tag is created which saves the UVW information. If you want to create a UVW mapping from the other projection types, use the object manager menu to create tags / UVW tags for polygon objects. For basic and spline objects, go to Object manager menu > Tags > C4D tags > Texture fixation.

Shrink mapping: With this type of mapping, the texture is placed over the object in a spherical shape and shrunk at the south pole, similar to the net on a hot air balloon.

Camera mapping: With camera mapping, a selected camera acts as a slide projector that projects the corresponding texture onto the object. To do this, the corresponding camera object must be dragged into the “Camera” field. If the camera is now moved or rotated, the projection changes accordingly.

- Side: This drop-down menu determines on which side of the surface normal the texture is displayed. The default setting is “Both” – ideal for logos on glass objects, for example.

- Tile: If a bitmap texture or a 2D shader does not completely cover an object, its structure is repeated by default, i.e. tiled like a floor tile.

- Seamless: This option sets texture tiles to mirror each other at their edges.

- Offset U/V: Irrespective of the projection type (sphere, surface, UVW, etc.), U denotes the width information, while V represents the height information. In the case of a 3D texture (e.g. 3D marble), a W coordinate for the depth would theoretically also be involved. If the U / V offset is changed, the start of the texture is shifted accordingly.

- Length U/V: Analogue to “Offset”, the texture can be scaled along U and V here.

Once you have finally applied your texture to the object using one or other projection type, further corrections to the position, rotation or scaling of the texture may be necessary. The projection of the texture on the object is displayed in C4D with a so-called texture cage. This is a yellow wireframe model that represents the selected projection type. This becomes visible as soon as you select the texture mode in the tool column on the left in C4D when the object is active.

An automated adjustment of the projection to the dimensions of the object can be carried out using the “Tags / Adjust to object” command in the Object Manager menu, for example. This adjusts the scaling of the texture cage to the dimensions of the object. Variations of the command also exist for adjusting to the size of the texture image, the size of an expandable frame or adjusting to various axes.

If you want to move, rotate or scale the texture cage as a whole, the most convenient way is to also activate the axis mode in the tool menu. The texture cage can then be moved, rotated or scaled along the axes accordingly. In principle, this procedure does not apply to UVW mapping.

In the next article in this series, we will look at how to use all this knowledge to create elegant, convincing textures and illuminate them credibly.